Things are getting ugly again in Europe, with multiple nations teetering toward default. Nations are beginning to play beggar-thy-neighbor with currency manipulations. Trade tensions are soaring. Austerity-minded politicians are on the rise. If you don’t hear the echoes of the early 1930s, you’re not paying attention. Or you might not have read about it. The American press isn’t exactly blanketing these stories.

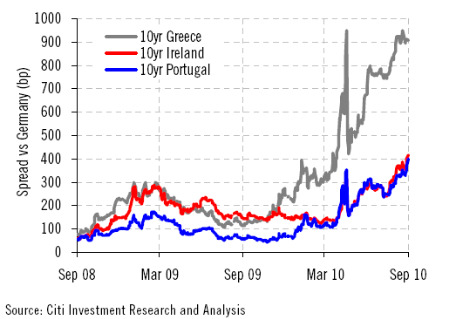

First look at a chart that ought to be concerning. These are credit-default-swap bond spreads for three of the so-called PIGS: Portugal, Ireland, and Greece.

CDS are instruments that insure against default. In this chart, those of Portland, Ireland, and Greece are measured against those of Germany, which is the safest of the European systems. When these spreads rise, it means the market is saying there’s a higher risk that they will default. These charts show that the market thinks Greece’s likelihood of default is back to where it was this spring when its troubles shook the world. Not as much coverage this time, no?

Both Ireland and Portugal’s CDS spreads are well above where they were during the initial bout of European sovereign crisis this spring. That brings us to the front page of Financial Times, which has done better staying on top of this stuff than its competitors, this morning: “Bank’s failure would ‘bring down’ Ireland, warns prime minister,” says the headline.

And so Ireland is upping its bailout of Anglo Irish Bank by nearly 40 percent to $48 billion. That will bring the country’s budget deficit to a stunning 30 percent of GDP. That would be like if the U.S. budget deficit—bad as it already is—hit $4.5 trillion this year.

Here’s how historian Harold James described the collapse of Austria’s Creditanstalt, which sparked a downward spiral in Europe (emphasis mine) that worsened the Great Depression:

In 1931, a fiscal crisis in Hungary followed a badly managed price support scheme for wheat and led to a loss of confidence by foreigners, who withdrew deposits and thus weakened the banking system.

Almost simultaneously in Austria. where there was no serious fiscal problem, the Creditanstalt was unable to publish its annual accounts. This triggered a bank run. The withdrawal of deposits highlighted the extent of the bank’s losses. Its assets had to be liquidated at vastly reduced depression prices. The government believed that it could not simply let Austria’s largest bank fail. As the bank’s losses became greater, the fiscal consequences of supporting it became graver. Austria, too, now had a fiscal problem.

Germany was next door yet had little capital participation in Austria. But depositors in German banks became nervous about Germany’s banks and the currency.

Starting from very different problems, all the Central European troubles eventually had something in common — falling commodity prices and fundamentally flawed banking systems on a very weak capital base. This produced a panic.

Hey, no falling commodity prices yet!

But indeed an Irish collapse would thunder around the world. Here’s the BBC:

Total foreign bank exposure to Ireland’s economy is $844bn, or five times the value of Ireland’s GDP or economic output. Of that, German and UK banks are Ireland’s biggest creditors, with €206bn and €224bn of exposure respectively.

To put it another way, German and British banks on their own have each extended credit to Ireland greater than Irish GDP. Which doesn’t sound altogether prudent, does it?

Bloomberg BusinessWeek‘s Peter Coy has a sharp column explaining why such creditors better prepare for haircuts, and why there’s no good path out of this mess:

Ireland illustrates why governments need to make private creditors share the pain. The bursting of its real estate bubble left the country overwhelmed with bad debts and forced the government to impose painful budget cuts. Embracing austerity has won Ireland the praise of the European Union — and little else.

The Irish economy shrank at an annual rate of 5 percent in the second quarter because the sharp reduction in government spending hasn’t been offset by a jump in private spending. And its borrowing costs have surged. Investors now have to pay 4.7 percent of the face value of Irish government bonds annually to protect against the risk of default for five years, 12 times the cost for insurance on German bonds….

One way or another, the world’s savers and investors are going to have to pay the bill for unrecoverable debts. The question is whether that happens in a rip-the-Band-Aid-off round of debt reduction or is dribbled out over years in the form of government-induced inflation (which will ease the burden of debt while eating away at the value of savings).

Meantime the FT has been all over the currency-devaluation angle recently. Here’s its economics commentator Martin Wolf warning yesterday:

“We’re in the midst of an international currency war, a general weakening of currency. This threatens us because it takes away our competitiveness.” This complaint by Guido Mantega, Brazil’s finance minister, is entirely understandable. In an era of deficient demand, issuers of reserve currencies adopt monetary expansion and non-issuers respond with currency intervention. Those, like Brazil, who are not among the former and prefer not to copy the latter, find their currencies soaring. They fear the results…

Could we even be seeing the starting gun for the next emerging market financial crisis?…

I would like to be optimistic. But I am not: a world of beggar-my-neighbour policy is most unlikely to end well.

And all of a sudden the U.S. is finally getting tough on China for manipulating its currency and killing American jobs. China has subsidized its exports to the tune of some 40 percent to 50 percent. And so the House of Representatives voted overwhelmingly—ninety-nine Republicans, too!—to give Obama the power to slap big tariffs on China if it doesn’t float its currency back to legit levels.

Japan has intervened in yen markets in the last couple of weeks to push its currency down (remember, strong currency makes it more expensive to sell your good to other countries and cheaper to buy their goods. That hurts jobs in the strong-currency country).

And to top it all off, analysts like Meredith Whitney are getting seriously worried about a rash of municipal defaults in the U.S., as cities and counties struggle underneath crushing debt burdens. Fortune calls it “the banking crisis all over again.” I don’t know if that’s hyperbole or what, but it’s worth worrying about. As is the bubble in corporate bonds.

Hold on to your hats—again.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.