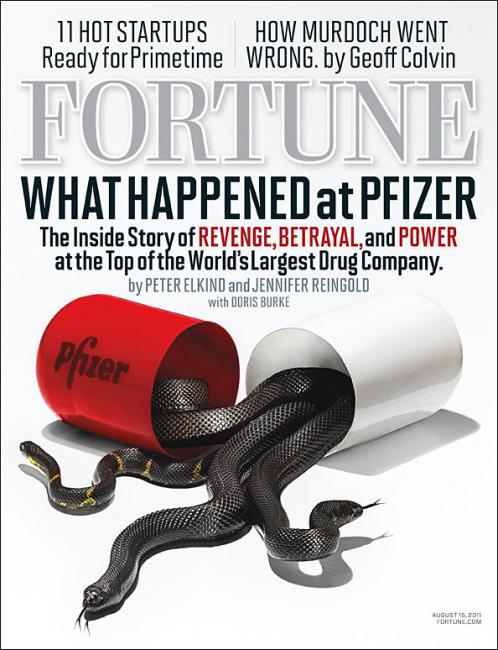

Fortune has a dandy read in this issue on an executive fiasco at Pfizer that led to the sacking of two executives, including the CEO. Or as it puts it on the cover:

WHAT HAPPENED at PFIZER

The Inside Story of REVENGE, BETRAYAL, and POWER at the Top of the World’s Largest Drug Company.

Believe it or not, that headline’s actually not very sensationalized, considering what Fortune‘s deep reporting shows. And the cover art is awesome: Snakes coming out of a giant Pfizer capsule:

This story is as inside a company as you can get. What makes it even more impressive is that Peter Elkind, Jennifer Reingold, and Doris Burke apparently had to write around the central figure, former CEO Jeff Kindler, who wouldn’t comment on the record for the story.

That didn’t matter much for this scene, which captures the moment the CEO realizes his power is gone:

For Jeff Kindler, it was a humiliating moment. The CEO of Pfizer, the world’s largest pharmaceutical company, had been summoned to the airport in Fort Myers, Fla., on Saturday, Dec. 4, 2010, for a highly unusual purpose: to plead for his job.

Three stone-faced directors, representing the company’s board, sat inside a drab airport conference room as the CEO, trained as a trial lawyer, struggled to argue his most important case. Alerted to this meeting less than 24 hours earlier, Kindler detailed his accomplishments, speaking nonstop for the better part of an hour. He touted his bold reorganizations, praised his administration’s sweeping cost reductions, and rhapsodized about his reinvention of Pfizer’s crucial research-and-development operations.

But the three board members, Constance Horner, a former deputy secretary at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; George Lorch, an ex-CEO of Armstrong World Holdings; and Bill Gray, a former Philadelphia congressman, weren’t there to debate the direction of the company. The board had spent a frantic week in an urgent investigation: A revolt had erupted against Kindler among a handful of senior managers, and the directors were trying to figure out what was going on. One possibility: an internal power grab. Another: a CEO who was unraveling.

Led by Horner, they confronted Kindler with questions about his management and his behavior. Had he routinely berated subordinates? Did he really bring senior executives to tears? And how did he respond to charges that his leadership style, a sort of micro-micro-management, had paralyzed Pfizer?

A questioner of prosecutorial intensity, Kindler was used to being the interrogator. But this time he had to respond, and his answers seemed only to harden the board members. Kindler insisted that just two executives were truly unhappy. Most of his team thought he was a good boss and had done great things for the company. What was the directors’ basis for concluding otherwise? Had they reviewed his sterling performance evaluations? Spoken to his executive coach?

That segues neatly into one of the themes of the piece: How Kindler’s background as an aggressive trial lawyer seemed to make him an ill fit for the C-suite of the biggest pharmaceutical company in the world.

Another interesting undercurrent here is how big companies resort to mergers and acquisitions when their prospects dim and how often it fails:

So McKinnell fell back on the refuge of the desperate pharma CEO: In July 2002 he announced the acquisition of Pharmacia, the industry’s seventh-largest company, for $60 billion in stock.

Lots of companies can run themselves. They have products that sell well and pipelines that regularly turn out new ones. Companies in withering industries like Big Pharma can make even the best CEOs look like mediocrities and the poor ones look like dog meat.

Pfizer’s R&D pipeline, like most others’, hasn’t produced any blockbuster dope lately. That’s not hard to fathom at a company that lost $3 billion on a diabetes bong with the Onion or SNL-style drug name Exubera.

Fortune shows with this story how a broken culture leads to disasters like that.

Meanwhile, its managers descended into behavior that would do Shakespeare — or Machiavelli — proud. There was the ex-CEO who couldn’t relinquish his power and quietly maneuvered to undercut two successors he had helped install. Then there was the human resources chief who divided the staff rather than uniting it. Most of all, there was Kindler himself, a bright man with some fresh ideas for reforming Pfizer but a person who agonized over decisions even as he second-guessed everybody else’s actions. The story of Jeff Kindler’s tumultuous tenure at Pfizer is a saga of ambition, intrigue, backstabbing, and betrayal — all of it exacerbated by a board that allowed the problems to fester for years.

But the real juicy part of the story involves Kindler’s HR executive Mary McLeod. Fortune reports that almost everyone was against her but Kindler. Fortune finds out that McLeod had gotten fired from the same position at Charles Schwab back in 2000, and it gets her former CEO on the record reading from her termination letter:

After an internal investigation, Pottruck fired McLeod in 2004, he confirms. In an e-mail sent to McLeod the day of her termination, read aloud to Fortune, Pottruck wrote: “The issues are about the perceptions others have of you around character, integrity and divisiveness … There is a perception that you do not tell the truth.”

McLeod helped bring down Pottruck and she did the same with Kindler too. But she lived large in the meantime, with Pfizer paying hundreds of thousands of dollars a year for a helicopter to shuttle her between Delaware and New York:

Apart from the terrible impression conveyed by an HR chief choppering to work in the midst of massive layoffs, someone soon realized that this arrangement posed another problem: McLeod’s emoluments were so lavish they might make her one of the company’s five most compensated employees, which would require Pfizer to disclose the details in its annual proxy statement. In early 2008 company governance chief Peggy Foran investigated the issue and tallied nearly $1 million in payments to McLeod, including those relating to her various houses, the helicopter use, and a large bonus to buy her out of a consulting partnership. Then there was McLeod’s salary and regular bonus of $900,000 and restricted stock and options.

Again, Pfizer was paying hundreds of thousands of dollars to chopper its HR chief back and forth from Delaware to New York.

There’s much more here. Read the whole thing.

It’s excellent work by Fortune.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.