I’ve never understood quite why, in a digital age that allows companies to sell directly to their customers, that book publishers, record labels, writers, and artists have allowed third parties like Amazon and Apple to seize outsize control of their industries.

J.K. Rowling doesn’t either, apparently.

The one-time billionaire has long resisted selling e-books of her Harry Potter series. Now she’s going to, but only through her own website Pottermore.com.

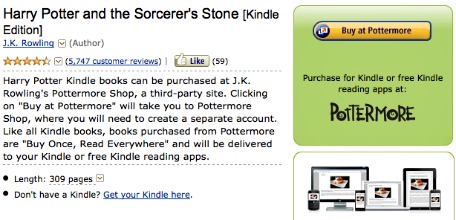

Such is Rowling’s market power that even Amazon, which dominates the ebook industry, is going along with her plan, and so has Barnes & Noble (Apple has not). Search Amazon for Harry Potter on the Kindle and you get this result:

That’s a link to Rowling’s site where you can only buy it there. Presumably, Amazon is getting a referral fee for that service. But you can bet it’s nowhere near the 30 percent it takes off the top for selling an e-book through its own site. For what it’s worth, here’s what Amazon pays news sites and blogs for sending customers its way, less than a third as much and usually a lot less than a third.

What’s more, when you buy Harry Potter via that Amazon link for your Kindle, you buy a copy that you’ll be able to read on any company’s e-reader, and it costs just $7.99 (though that’s probably so low because Rowling owns her digital rights). Typically when you buy a book through Kindle you’re stuck on the Kindle. That’s a big reason I, for one, still haven’t bought an e-reader. I don’t want to buy a bunch of books in one format and then not be able to purchase a different brand of e-reader.

The Guardian Philip Jones puts it this way:

In bringing these books to the digital marketplace, Pottermore, the business created to sell the ebooks, has forced Amazon into perhaps the biggest climbdown in its corporate history.

Instead of buying the ebooks through the Amazon e-commerce system, the buy link takes the customer off to Pottermore to complete the purchase, with the content seamlessly delivered to their Kindle device. It is the first time I’ve known Amazon to allow a third party to “own” that customer relationship, while also allowing that content to be delivered to its device. Amazon gets something like an affiliates’ fee from this transaction, much less than it would expect to receive selling an ebook through normal conditions. Schadenfreude doesn’t even come close.

Joshua Gans says “JK Rowling blows up the eBookstore business.” Maybe not, but this example very well could blow up the ebookstore business. I’d say it should blow it up. And hopefully it blows up the nascent e-newsstand business as well.

Right now these bookstores serve as chokeholds on a market that should be wide open if content producers want it to be. Here’s The Guardian‘s Jones again.

Amazon has a stranglehold over the ebook market both in the UK and in the US (though particularly in the UK where there is no Nook to challenge it)…

Many in the publishing business worry about this, and rightly so. Amazon seeks to dictate terms that are making many publishers feel uncomfortable: in the US it has recently locked out numerous independent publishers, simply because they cannot agree to its demands.

You can also see this in that they’re able to take 30 percent off the top of somebody else’s content. Should it really cost nearly one-third to retail a digital product?

Apple’s Newsstand has been hobbled somewhat by the 30 percent fee it charges media companies to sell their apps there. The New York Times and Vogue are there, sure, but the Financial Times and Wall Street Journal are not—and you can’t really have a newsstand without those publications. Apple’s 30 percent wouldn’t be much of a problem if it were a one-time transaction cost. But if you buy a recurring subscription through Newsstand, Apple gets a 30 percent cut of every transaction in perpetuity—plus Apple controls the customer relationship. That’s ridiculous.

With the Justice Department ramping up its apparently silly collusion case against the book publishers for agreeing with Apple to set their own prices, Rowling is showing that publishers and authors really do have the pricing power—if they’ll just use it.

It’s true that no other author comes close to having the power Rowling does. If the author of the Unofficial Harry Potter Cookbook, say, goes to Amazon and tries to get the same deal, Amazon will probably tell her to get lost.

But if Random House or Simon & Schuster told Amazon et al. they were following suit, the booksellers might have to play along. That way publishers could legally control the price of their products while reducing the fees they pay to intermediaries and creating a sales infrastructure that costs far less than 30 percent.

Amazon and Barnes & Noble can still sell their Kindles and Nooks for however much they can get for them. And publishers and authors can do the same with their products.

The big problem here is that such a system would make buying books more of a hassle–forcing readers to input their credit card and address data each time they make a purchase. Publishers and/or authors would need to figure out how to fix that. They’d better get started.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.