Will The New York Times Company survive as a stand-alone firm past 2015?

That’s unknowable, of course. A lot can happen between now and then. But extrapolating from current trends can give us an idea of where things are going.

That’s what Ironfire Capital’s Eric Jackson does for Forbes, arguing that trendlines suggest that the “basket-case” of a company likely will either be in bankruptcy or forced to sell to someone else within three years.

Certainly this is not a healthy business. Forbes, for one, knows better than most about being a financial basket-case.

This is a welcome exercise, but for the NYT (I will italicize NYT when I’m referring to the newspaper rather than the company as a whole), I don’t think trendlines suggest that the company will face an existential crisis in the next three or so years.

Jackson links to a brief Power Point presentation (see the bottom of this post) he put together that notes that “Cost reductions have hit a plateau recently” and that “Ad revenues appear set to continue declining without help from paywalls or other digital efforts.”

As far as cost reductions,The New York Times has sacrificed some short-term profits in order to keep the news staff at its flagship paper beefed up. There have been no Los Angeles Times or Washington Post-style newsroom massacres there, and the NYT still has the biggest newspaper staff in the country. While I obviously hope it won’t have to, it could cut more staff if it ran into cash problems.

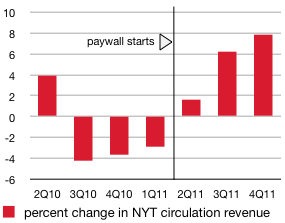

But while overall ad revenues are likely to keep falling for several years—they were down about 3 percent last year—paywalls have helped. At the New York Times itself, the ad declines were more than offset by increased circulation revenue from the paywall. Here’s another trendline for you:

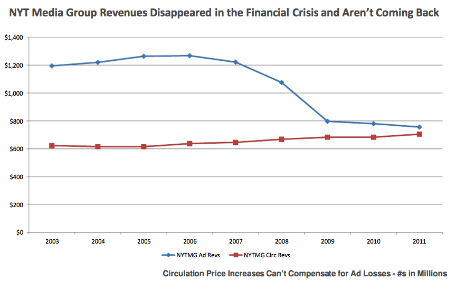

Remember, circulation is not the relatively minor revenue stream it historically has been at newspapers. While circulation at most newspapers has historically been about one-third or one-fourth the amount of ad revenue, that has changed in the past few years as ads have been decimated and circulation revenues have held up relatively well.

Circulation in 2012 will become the primary revenue source at the NYT for the first time (on an annual basis), eclipsing advertising. You can see that from Jackson’s chart:

Jackson also says that “Cash at the end of 2011 was $280 million, down from $400 million at the end of 2010.”

While that’s true, it’s worth noting that six days after the end of 2011, the NYT sold its Regional Media Group, which it says will add roughly $150 million to its cash position (and reduce its head count by 1,700). That unit underperformed compared to the dominant NYT unit.

Jackson asks why Carlos Slim and other financiers would want to refinance the NYT’s debt. I don’t know about other financiers, but Slim doesn’t have anything to refinance. The Times paid him back last year.

And that Slim payoff is important, and not just because it will save the company $39 million a year through 2015. Most of last year’s decline in cash was due to the company’s decision to pay off the Mexican billionaire’s $250 million loan three and a half years early. While that loan was at a usurious 14 percent rate, paying a note off in less than half its six-year term isn’t a hallmark of a cash-desperate company. Neither is the fact that the NYT has a $125 million revolver that is so far untouched.

Moreover, by selling its regional media group, the company has added about $150 million to the $280 million cash position Jackson cites, bringing it back above 2010 levels. In February, it also cashed out some of its remaining Boston Red Sox stock for $30 million and still holds more than $60 million of that business.

And the NYT still has a couple of other things it could sell if worse comes to worst. Admittedly, this is, in effect, eating its seed corn, and I don’t recommend it, but since we’re talking about cash needs:

The NYT’s About.com is still worth quite a bit of money even though it’s been hammered by Google’s anti-content farm algorithm changes,. It kicked off $41 million in operating profit last year on $111 million in revenue. The Boston Globe, if it needs to be jettisoned, would surely fetch tens of millions of dollars from some rich Bostonian.

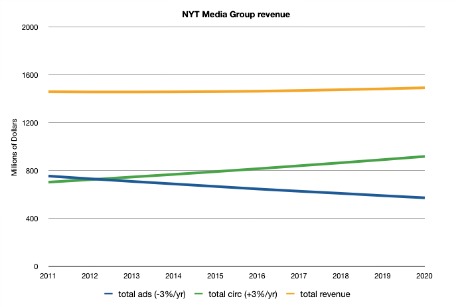

If ads continue to on their current trendline, falling 3 percent a year from the $756 million it reported in 2011, the Times will end 2015 with about $690 million in ad revenue. A 4 percent annual decline would drop that to $668 million. The Times can tread water by increasing circulation revenue by the same percentage ad revenue declines.

Is that possible? It looks like it.

Since 2006, Times circulation revenue has already been rising a bit more than 2 percent annually (compound annual growth rate), moving from $637 million to $705 million last year. That was during the worst five years in the history of the news business, with print circulation plunging and with Times ads falling nearly 10 percent a year.

Only the last nine months of those five years benefited from a paywall, which not only adds a new, high-margin revenue stream but helps protect print circulation a bit. The Times‘s digital subscriber count has risen 17 percent a quarter since the first three months of the paywall and the paper recently raised newsstand prices.

Adding 3 percent a year would mean $88 million a year in additional circulation revenue by the end of 2015. The Times ought to add at least half that this year.

The pension problems Jackson points to are a little dicier and worth watching closely. So far, they’re manageable, with the Times only required to put in a fraction of the shortfall. If that requirement grows substantially it will eat into the paper’s cash.

Again, the point is not that The New York Times Company is all well. It’s obviously not. And it just might be better off in the long run with a Michael Bloomberg-style owner. Its medium-to-long-term health as a stand-alone company will depend on its ability to slowly draw down print advertising and circulation while and replacing that revenue with digital ads and subscriptions.

Right now, for the first time in a long time, the company isn’t bleeding to death and it has added a fast-growing revenue stream to a stable, slow-growing one.

But if print ads start tumbling 20 percent a year again all of a sudden, all bets are off.

The New York Times Stares Into the Abyss

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.