It’s hard to remember a more flattering profile of an important CEO than the one gracing the cover of the current Fast Company.

The headline is “King Bezos,” and there doesn’t seem to be much irony lacing through there.

The subhead is: “Inside the 3-part plan to make Amazon the most loved* company in world.” The asterisk points to a note: “Also the most feared by Apple, Netflix, Google, Walmart, EBay, and more.”

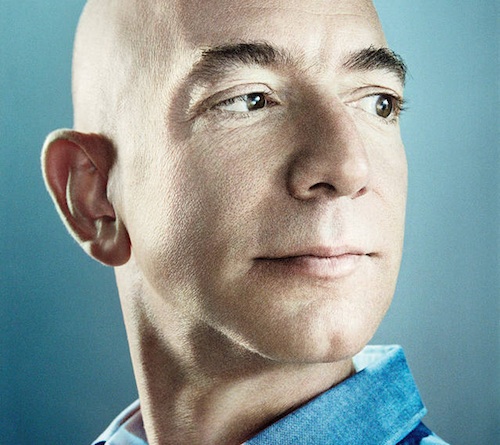

The photographs are even more iconographic than the usual business-press big-shot-on-the-cover-format. You really have to see the print edition to appreciate it, but this gives the idea:

The story begins:

A surprisingly diminutive figure, clad in blue jeans and a blue pinstripe button-down, Bezos flings open the door with an audible whoosh and instantly commands the space with his explosive voice, boisterous manner, and a look of total confidence. “How are you?” he booms, in a way that makes it sound like both a question and a high-decibel announcement.

Of course, anyone would seem diminutive in real life after the buildup Bezos gets in this and other friendly outlets. Overall, the piece brings to mind this insight on how Bezos uses the press to his advantage from a recent profile by The Washington Post‘s Peter Whoriskey (with my emphasis):

Richard L. Brandt, who wrote an unauthorized biography called, “One Click: Jeff Bezos and the Rise of Amazon.com,” said Bezos shuns newspaper reporters in favor of a few business and technology reporters at high-end magazines. Bezos grants them interviews at times that best suit him, such as when he is rolling out a new product.

“He selects the journalists he wants to work with rather than them selecting him,” he said. “With the rest of us, he gives very little away.

When the Allentown Morning Call asked for comment on its epic series on sweatshop working conditions at Amazon warehouses in Pennsylvania, Amazon didn’t respond—at all. It just ignored it. This is bush league.

All this is not to say the Fast Company story isn’t interesting and informative. It is both. As I’ve written, access reporting—and that’s what this is—has its place, and access to Bezos here yields valuable information: namely, that Amazon plans to expand a same-day delivery service it has for groceries in Seattle to the rest of its vast inventory—and across the country. Coupled with the company’s $79-a-year Prime delivery option, which incentivizes customers to use the site constantly for all manner of goods, the potential for Amazon further expanding its dominance of retail—and the delivery business—becomes apparent.

But it’s the article’s tone that’s so striking. So upbeat! Some snippets:

Amazon has done a lot more than become a stellar retailer. It has reinvented, disrupted, redefined, and renovated the global marketplace

…

Amazon’s 1-million-square-foot Phoenix fulfillment center produces a steady and syncopated rhythm

…

Given the astounding growth of Amazon, and the seemingly infinite ways it has defied the critics, Bezos may have proved himself the best CEO in the world at taking the long view. But he doesn’t like talking about it.

And so on. The critical distance here is razor thin.

There’s also an unnecessarily generous treatment of Amazon’s decades-long scorched-earth fight not to collect state sales taxes, which gave a huge, and hugely unfair, price advantage over bricks-and-mortar retailers.

Having gamed the system for years, Amazon has finally lost the fight. But now, we learn, it’s using its new-found heft to build enough warehouses near urban areas so that its expanded same-day delivery service can offset the expenses of paying taxes like everybody else.

For Fast Company, that’s an applause line, a “cunning shift in tax strategy.”

But Amazon has since changed its mind. It determined that the benefits of more fulfillment centers–and all the speed they’ll provide–will outweigh the tax cost they’ll incur. So it began negotiating with states for tax incentives…

Quoting a friendly consultant:

“The general perception is companies thinking, Oh, great, finally a level playing field,” Rossman says. “But other retailers are going to regret the day. Sales tax was one of the few things impeding Amazon from expanding. Now it’s like wherever Amazon wants to be, whatever Amazon wants to do, they are going to do it.”

As Peter Elkind and Doris Burke’s investigation earlier this year in Fortune showed, Amazon’s tax avoidance strategy was not marginal to the company, but part of its very DNA, from Bezos originally plotting to start Amazon on an Indian reservation to avoid collecting taxes forward.

It was gaming the tax system that was key to Amazon’s ability to launch its new same-day initiative. Manipulating the tax system does not mean you are a better retailer. That is not innovative. That is old school. It calls to mind what Ida Tarbell wrote about John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil in her memoir more than 30 years after her epic series on the monopoly:

I never had an animus against their size and wealth, never objected to their corporate form. I was willing that they should combine and grow as big and rich as they could, but only by legitimate means. But they had never played fair, and that ruined their greatness for me.

But all that aside, there’s no inkling whatever that there might be some downside to Amazon’s march to victory, no sense of misgiving along the lines of this bit from Whoriskey’s story:

“To this day, whenever I walk into a bookstore I like, I hang my head in secret shame,” said one of the earliest employees, who for personal reasons asked that his name not be used.

And I wonder, even if Amazon is successful, whether the “entire retail experience” is really so very important in the scheme of things as Fast Company makes it out to be.

Still, whatever qualms you might have about this story, it does at least have the merit of providing, if inadvertently, any number of excellent reasons why it would be better to have someone other than Jeff Bezos owning the most important newspaper in the nation’s capital.

Since the topic here is journalism reinforcing elite power, it’s worth flagging that properly criticized (item 3) New York Times profile of Katharine Weymouth. As Ryan Chittum soberly points out, Weymouth is part of the team that shares no small responsibility for a paper with real potential to survive the digital onslaught instead staggering blindly for years before collapsing into the arms of Rockefeller Bezos.

Let’ s just call it “Exhibit B,” and leave it at that.

Dean Starkman Dean Starkman runs The Audit, CJR’s business section, and is the author of The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism (Columbia University Press, January 2014). Follow Dean on Twitter: @deanstarkman.