The New York Times continues its excellent series on The New Poor with a look at Memphis, and the socioeconomic damage wrought by the mortgage crisis.

These are hard stories for the business press to tell well. As we’ve said before, they demand creativity and persistence.

The NYT’s Michael Powell has done well on this beat before, including a piece a year ago, with Janet Roberts, about how black and Latino homeowners were hit especially hard when the foreclosure crisis hit New York. The Journal delivered a memorable story a few years ago, about how the subprime mess was battering Detroit’s middle class.

These stories are out there, afflicting whole communities and entire classes—especially low-income strivers who had made it up the first rung of the economic ladder. And, as the Times shows, they’re very much worth telling.

Powell’s latest piece has plenty of good on-the-ground reporting, lots of data, and disturbing details about lawsuits around the country against big mortgage lenders that the business press should be tracking carefully. But the story’s biggest strength is the way it pushes past the now-routine stats about foreclosure rates and unemployment trends to get to an under-told story of the crisis:

Not so long ago, Memphis, a city where a majority of the residents are black, was a symbol of a South where racial history no longer tightly constrained the choices of a rising black working and middle class. Now this city epitomizes something more grim: How rising unemployment and growing foreclosures in the recession have combined to destroy black wealth and income and erase two decades of slow progress.

The Times looks at several strands of the story. With the help of the sociology department at Queens College, it reports that the median income of black homeowners in the city was rising steadily until five or six years ago. “Now it has receded to a level below that of 1990—and roughly half that of white Memphis homeowners.”

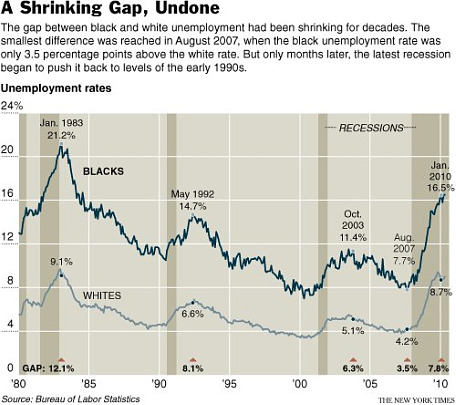

The unemployment front is bad, too, and what’s happening in Memphis mirrors what’s going on in the rest of the country. It’s not just that the unemployment rate among blacks is higher than that among whites. It’s that the gap between black and white unemployment had been shrinking, only to shoot up again with the recession. This chart tells that bit of the story:

But the Times also looks forward, connecting what’s happening now with prospects for the future by looking at the “the steadily widening gap between the wealth of black and white families.” These are numbers we don’t see a lot, and they’re jarring. The Times points to a recent Fed study, which found that, “for every dollar of wealth owned by a white family, a black or Latino family owns just 16 cents.” But it’s worse than that:

The Economic Policy Institute’s forthcoming “The State of Working America” analyzed the recession-driven drop in wealth. As of December 2009, median white wealth dipped 34 percent, to $94,600; median black wealth dropped 77 percent, to $2,100. So the chasm widens, and Memphis is left to deal with the consequences.

That’s awful, but important, and the Times does a great job of explaining why:

Blacks only recently began to close the home ownership gap with whites, and thus accumulate wealth — progress that now is being erased. In practical terms, this means black families have less money to pay for college tuition, invest in businesses or sustain them through hard times.

“We’re wiping out whatever wealth blacks have accumulated — it assures racial economic inequality for the next generation,” said Thomas M. Shapiro, director of the Institute on Assets and Social Policy at Brandeis University.

Yes, he said, “the next generation.”

There are other strong elements to the piece, including excellent, on-the-ground reporting that captures the mood of Memphis, and a powerful slideshow online.

There’s also good reporting on allegations that Wells Fargo and other large national banks “singled out blacks in Memphis to sell them risky high-cost mortgages and consumer loans.”

It’s a lot to unpack, and the Times does it well. With its many strands, the story also points the way to many more, stretching far beyond Memphis. There’s plenty more work for the business press to do on this front.

— Further Reading: