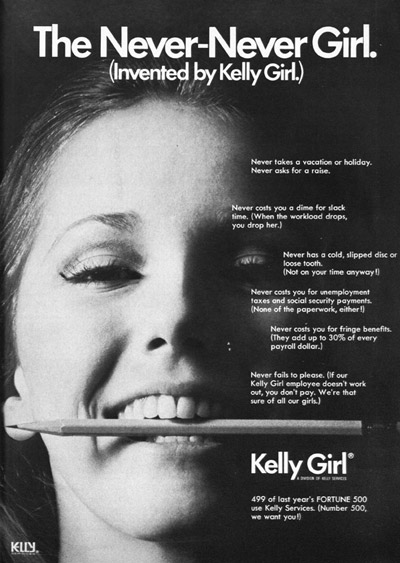

Deep in its investigation of the temp industry, ProPublica prints this 1971 ad for “Kelly girls”:

Here’s the text:

Never takes a vacation or holiday. Never asks for a raise. Never costs you a dime for slack time. (When the workload drops, you drop her.) Never has a cold, slipped disc or loose tooth. (Not on your time anyway!) Never costs you for unemployment taxes and social security payments. (None of the paperwork, either!) Never costs you for fringe benefits. (They add up to 30% of every payroll dollar.) Never fails to please. (If our Kelly Girl employee doesn’t work out, you don’t pay. We’re that sure of all our girls.)

Left unspoken, but clearly understood by employers in an otherwise remarkably forthright advertisement: “Never organizes a union” and “never goes on maternity leave.”

In an era when workers still had real power, this was a tantalizing pitch to employers, who were on the cusp of upending the power relationship between capital and labor.

Four decades later, unions are routed, median income has stagnated, capital owners and management have taken the vast majority of the economic gains, Kelly Services is the second largest employer in the country, and poor, largely immigrant workers are forced to pay an eighth or so of their wages to be driven to and from work by a “raitero” in a minivan stuffed with 17 people. After the raitero vig and the unpaid waiting time, ProPublica reports, average wages often dip below the legal minimum, which is already abysmally low.

And that’s if they’re lucky enough to get “hired” for the day:

Even though some assignments last months, such as her recent job packaging razors for Philips Norelco, every day is a crapshoot for Rosa. She must first check in at the temp agency in Hanover Park, Ill., by 4:30 a.m. and wait. If she is lucky enough to be called, she must then take a van or bus to the worksite. And even though the agency, Staffing Network, is her legal employer, she is not paid until she gets to the assembly line at 6 a.m.

The U.S., naturally, grants its temporary employees far fewer protections than other advanced economies, and taxpayers end up paying for it via the social-welfare system:

ProPublica’s Michael Grabell makes a case that the $134 billion temp industry is something of a reputation laundry for giant PR-sensitive corporations like Walmart and compares the firms to the “labor sharks” of a century ago (emphasis mine):

Many people believe that the use of temp workers simply grew organically, filling a niche that companies demanded in an ever-changing global economy. But decades before “outsourcing” was even a word, the temp industry campaigned to persuade corporate America that permanent workers were a burden.

The industry arose after World War II as the increase in office work led to a need for secretaries and typists for short assignments. At the time, nearly every state had laws regulating employment agents in order to stop the abuses of labor sharks, who charged exorbitant fees to new European immigrants in the early 1900s. Presenting temp work as a new industry, big temp firms successfully lobbied to rewrite those laws so that they didn’t apply to temp firms.

We’ve come full circle now. In some towns, ProPublica reports, it’s difficult to get manual labor without going through the labor sharks… er, staffing agents.

Particularly in a depressed job climate, a temp economy makes it much easier to treat workers like garbage, as we’ve seen with companies like Amazon.

Which brings me to Spencer Soper of the Allentown, Pennsylvania Morning Call, who has done fantastic work on that, breaking the story of Amazon’s sweatshop in the Lehigh Valley back in 2011.

The company’s warehouse managers kept ambulances waiting outside its un-air-conditioned facilities because its workers were passing out from the heat. ProPublica reports that temp workers are much more likely to be injured on the job, presumably because they’re less familiar with what they’re doing but also because employers have less incentive to keep them safe.

Late last year Soper followed up with another terrific investigation into how Amazon’s temp firm battles its workers on unemployment claims and it’s worth revisiting.

Soper reported that one Amazon warehouse worker filed for $160-a-week unemployment checks. Amazon’s temp firm Integrity Staffing Solutions fought her, claiming she got fired when she didn’t show up to work.

Fritchman, 67, remained poised and gave a detailed account about how she struggled working in brutal heat until medical personnel examined her and told her to go home. Following company policy, she provided a doctor’s note upon returning to work, and she was still terminated without explanation, she said…

… (ISS’s) Golbreski did not dispute any of Fritchman’s testimony about suffering heat exhaustion or bringing in a doctor’s note.

“I don’t have that information,” Golbreski said in response to Fritchman’s testimony. “I’m not aware of that.”

Participants in an appeal can question one another and Fritchman asked Golbreski if workers sent home early due to health concerns still get demerits. Golbreski responded: “I believe that is correct.”

Fighting unemployment claims (some of which are indeed spurious, Soper reports) keeps the temp agency’s unemployment insurance costs down. Amazon keeps its own down by offloading its responsibility to employees to a little-known third party:

The very nature of Amazon’s business, which requires thousands of temporary warehouse workers during the busy holiday shopping season, would leave it prone to high costs for unemployment insurance. Temporary-staffing firms create a buffer between Amazon and higher unemployment insurance costs because temporary warehouse workers are employees of the agency, not Amazon.

Pennsylvania wouldn’t release records to Soper on how many unemployment cases Amazon’s temp firm fights, but one state source told him it was in the hundreds annually—more even than Walmart, and one of the most frequent appeals filer in the state. The unemployment-claims practices of ISS, which operates for Amazon in several states, and other temp firms might make for good investigations elsewhere.

This SUNY professor quoted by Soper pretty much sums it all up:

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.“They can treat these workers like a disposable commodity, because there are so many more people in line,” Gonos said.