The Financial Times‘s Alphaville and Reuters’s Felix Salmon take down both sides of a Boston Federal Reserve paper finding that economists who called the housing bubble were basically just lucky—”That Reasonable People Did Disagree” on whether there was one, and the bulls had a reasonable case.

Yikes:

…we review the arguments of a prominent pessimist, Paul Krugman. Although his arguments were made in his widely read New York Times column rather than in a formal academic paper, Krugman, now a Nobel Prize-winning economist, has substantial credibility. He argued that because it is difficult to build in coastal areas of the United States, those areas are more “bubble-prone.” Consequently, the rapid price increases on the coasts but not elsewhere were prima facie evidence that there was a bubble and that prices would eventually collapse.

It is tempting to call Krugman prescient because beginning in late 2006 prices did indeed crash. But his arguments were problematic both ex ante and ex post. Ex ante, it is unclear why Krugman thinks the coasts are more “bubble-prone.” The models we have of asset-price bubbles do a reasonable job explaining why they can persist but have little to say about where we might expect them to start. As one prominent researcher in the field writes, “we do not have many convincing models that explain when and why bubbles start.” Krugman’s thesis seems to hinge on the idea that scarce coastal land is valuable and bubbles can only happen when assets are in short supply, but the whole point about bubbles is that the fundamentals of supply and demand do not matter. Thus, there is no reason why land in places where it is easy to build could not experience bubbles.

Well, see, Krugman, in the two words the Fed quotes, says “bubble-prone,” not that “bubbles can only happen when…” Hand meet forehead.

Zero in on this part: “the whole point about bubbles is that the fundamentals of supply and demand do not matter.”

But they do. I’m a mere layman, but it seems to me that bubble get started because of some shortfall in supply that pushes prices up rapidly, causing a surge in demand that then seriously outstrips supply. Like, say, in non-coastal Las Vegas, where developers couldn’t build houses and condos fast enough, driving up their prices.

Or in coastal areas, reasonable demand sends prices rising much more quickly much faster than in, say, Oklahoma, because the supply is much more constrained. Those quick price increases cause buyers to jump in either to make some money or to lock in a place before prices go up even more. That sends prices higher and higher.

As Alphaville sums it up:

IT’S NOT ECONOMISTS’ FAULT IF THEY FAILED TO MISS THE HOUSING BUBBLE BECAUSE THE EVIDENCE COULD HAVE GONE EITHER WAY, AND ANYWAY ECONOMICS IS NOT MEANT TO IDENTIFY ASSET BUBBLES, AND BESIDES EVEN IF WE HAD PREDICTED A BUBBLE NO ONE WOULD HAVE LISTENED TO US. AND PAUL KRUGMAN’S COASTAL ARGUMENT WAS WRONG.

SO THERE.

Salmon points out that the authors, Kristopher S. Gerardi, Christopher L. Foote, and Paul S. Willen, say this:

If housing was so obviously overvalued, as the pessimists suggested, then investors stood to make huge profits by betting against housing. By doing so, investors would have ensured that house prices would have fallen immediately.

Salmon punctures that by noting how difficult it is to bet against housing:

… applying this argument to housing bubble makes even less sense, because it’s almost impossible to bet against housing. You might be able to short proxies for the housing market, like real-estate investment trusts or homebuilding stocks. But you can’t short houses themselves. And the handful of people who did manage to make money by shorting the housing market only managed to do so after Wall Street spent a huge amount of time, effort, and money creating credit default swaps on collateralized debt obligations comprising a large number of thin slices of private-label subprime mortgages. Such things didn’t even exist for most of the housing bubble, and even after they were invented they were available only to a very small number of dedicated housing bears.

And even when the Wall Street types were able to short housing, it ended up becoming a key part of why the bubble kept inflating. Apparently these guys have never heard of Magnetar.

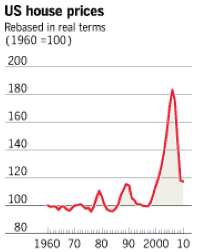

But one chart belies all the academic mumbo-jumbo the Fed can muster. This from today’s FT:

If you couldn’t see a bubble there, you’re probably not going to see one anywhere.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.