LONDON—The New York Times‘ efforts to adapt to the digital age gets all the attention, for better and for worse.

But actually, the most successful English-language news organization in navigating the transition from a print-centered to a digitally oriented operation is the Financial Times, the UK-based business paper.

And if there’s a man behind the curtain, it would be Rob Grimshaw.

Grimshaw is the managing director of FT.com and architect of the metered subscription model—allowing some free stories before asking readers to pay—that was launched in 2007 and which the Times copied four years later. He’s also guided the data-intensive marketing operation that turned the newspaper from an industrial company into what is now effectively an online retailer of its content. Along the way, the FT, a unit of Pearson PLC, achieved a few other important firsts: It was first to earn more revenue from readers (subscriptions) than from advertisers, reversing the model on which newspapers have relied for decades. It was first to earn more from digital operations than from print, going truly “digital first.” See this post of mine from 2012 for more details.

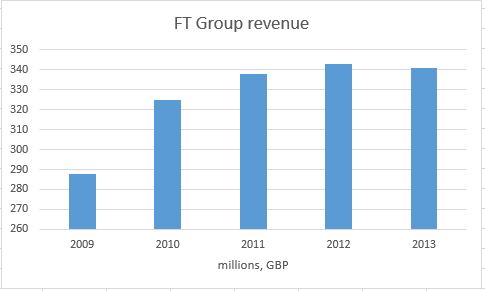

And most importantly, it was first to successfully replace falling print revenue with digital income. In other words, while it’s great to be digital first, it’s not so great if that only means that digital revenue caught up only because print was falling so fast. That has not been the case with the FT, as this graph shows (keeping in mind 2009 was an anomalously down year; the trend is basically flat):

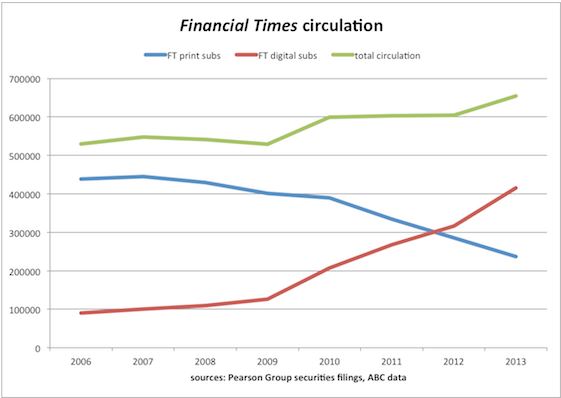

That’s largely thanks to the paywall and the rise of digital subscriptions, which Ryan Chittum documented here:

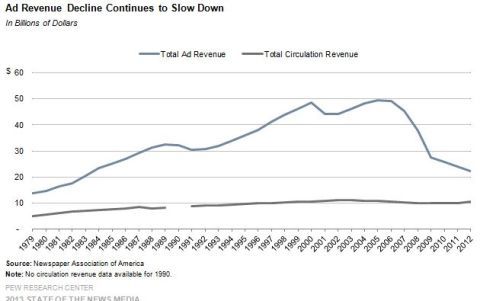

And this, remember, was when the rest of the industry was in free-fall, so flat growth is no small achievement. Here’s a look at that via Pew:

Some chunk of the credit redounds to the self-effacing Grimshaw, 42, who joined the FT in 1998 after stints at other UK news organizations and became an FT.com executive in 2000. A graduate of the University of Warwick in philosophy and political science, Grimshaw’s professional background, importantly, is not in technology or editorial, but in advertising, a bit of a paradox given that the reader-centered model he engineered represents a move away from advertising. Along the way, the FT took a couple of big risks: lowering the meter to force more people to pay sooner, which risked alienating causal readers and causing ad-driving traffic to fall; and developing its own digital application using a common coding language, known as HTML5, rather than selling the FT through the Apple store, as other media outlets have done. Both worked out, and ever since, Grimshaw has been in demand to discuss the FT’s model around the industry.

The big question for the newspaper business is the degree to which the FT’s model is replicable to other newspapers, particularly American regional general-circulation newspapers. What parts of the model can be copied?

One notable element of the FT’s strategy, for instance, is that it has avoided the dramatic newsroom cuts carried out by the rest of the industry. The FT now has about 550 newsroom employees, up from 450 in 2006. Industry-wide, newsroom employment is down more than 30 percent in the same period. In this, the FT is similar to the Times and The Wall Street Journal, both, as it happen, also successful paid content providers.

Still, it’s important not to overstate the case. The FT’s audience is very well heeled and pays at least $325 a year in the US and $450 a year in the UK for a digital subscription alone. What’s more, the FT does a good business (which it doesn’t break out) selling subscriptions to corporations, essentially a business-to-business operation that isn’t replicable by general-circulation newspapers.

Still, Grimshaw is adamant the FT’s model can be copied. I sat down with him last month at his glass, cube-shaped office overlooking the Thames at the FT’s headquarters in London’s Southwark section. The conversation has been heavily edited for conciseness.

Dean Starkman: Which philosopher has been most useful to you?

Rob Grimshaw: (Laughs) That is a good question. You know Kierkegaard actually. I mean faith is quite important for the digital business. You have to believe it’s going to work out.

DS: Would you describe the period of trial-and-error that got you to this moment?

RG: We put the paywall online in May 2001, and it worked okay but it didn’t work that well for six years after its inception. There were a couple of reasons for that. We had got a poor model. It was a very straightforward paywall. Some stuff was behind it and some stuff was in front. We didn’t have the expertise as an online retailer to know why it wasn’t working as effectively as we thought it might. And also the advertising business in that stage was booming. The growth trajectory on [digital] advertising was very, very strong.

DS: People forget that.

RG: Absolutely. Through that period, whether it was us or whether it was anyone else in the marketplace, you were making very strong, double digit growth on digital advertising… until maybe 2006-2007 other than the exception of the years immediately after the dotcom bubble burst, 2001-2002. And remember, this is a time pre-social media. Google was [just] starting to be a force in the market. There were many people at the FT and elsewhere who were saying advertising is working, so why do we need to worry about this [subscription] stuff? I think we came to the end of that road quicker at the FT than other publications because we lacked scale. It’s obvious that we are not going to achieve the scale of a Yahoo. It became clear that unless we had a fundamental change in the way we approached editorial, we were always going to a niche site on the web. Our traffic figures were always going to be a constraining factor.

DS: So what was the turning point for the digital side, meaning emphasis moves from advertisers to subscribers?

RG: The turning point was two-fold: Firstly a new model being put in place, the famous model now being used by the Times and hundreds of publications across the US. And that went in in November 2007 and it was a model which was much better adapted to the web… We started to see upticks right away. But …it was implemented relatively timidly at first in order to avoid harming the advertising business.

The second big change came when the advertising guy took over the business, which is me. And actually having been very close to advertising, conscious of the fact that advertising wasn’t going to do the growth that everybody wanted it to, we needed an alternative. And that to me, meant being much more bold on the subscription side, and pushing, turning the dial on the meter model over toward subscription.

DS: Turning the meter down to give away fewer free stories?

RG: 2008 is the moment where we really accelerated down on the subs model, and we took a little gamble on the advertising side. My bet was that as people took up subscriptions they would spend more time on the site, and we would have tools that would help us to do that, because if someone is a subscriber, you can email them, you can bring them back to the site more often. That’s what happened. As a result, even though we got much more aggressive with the positioning of the barriers, traffic on the site really did not dip.

DS: That was the fear, yes?

RG: Absolutely. And we actually since that point in 2008 have grown our advertising revenues every single year. And generally, either in line with or ahead of the marketplace. There has been no or very little price to pay on that side of things. The gain on subscription side has been enormous, because what we found was, as soon as we pushed hard on this, and we turned the dials on the model to the point where many people were coming up to barriers, a lot of people went through, and more than that, they were happy to come through at price points that were far above what any of us had anticipated.

DS: Help me understand the HTML 5 issue: what was the choice there, what was the challenge?

RG: The challenge was Apple’s terms and conditions, which had two problems. The first is the Apple tax, they wanted to take 30 percent of every transaction around our subscriptions, every acquisition and renewal. And it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to pay 30 percent to somebody else’s billing platform when you’ve already built your own at great expense, so that was a headache. The second big thing, which in many ways is more important, is Apple wanted to intermediate in our relationship with our customers. Now we knew, because we had a pretty mature model at that stage, that the relationship with the customer is absolutely crucial. If, for example, you wanted to manage your churn rate effectively, you need to be able to talk to your customers; you have to have that direct channel if you want to upsell, if you want to market other products, etc. etc. If you want to bring your customers back to the site on a more regular basis, you need to have that relationship…When you add it all together, we knew that around 60 percent of the value of a subscription to us would disappear if we went through the Apple channel.

DS: 30 percent plus the other 30 percent.

RG: Exactly. It’s a big deal.

DS: Why is data so important for publishers now?

RG: For example, we try to get hold of every customer who cancels, and what we find is that not every cancellation is the same. It’s very common for example for people to cancel simply because of a payment failure, their credit card we hold for them is out of date, they forget to update it, the payment doesn’t go through, and just by putting in a call or sending an email, it’s a prompt reminder that gets people to go, “Oh, I didn’t mean to cancel that. I’ll go and fix that.”

DS: Simple things.

RG: Very simple things. And a huge portion of the people we get hold of actually will resubscribe, and that business is worth millions and millions of pounds. Other areas is simply people not having full understanding of the product. So it’s not unusual for our customer services to have conversation along the lines of “Do you know why you’re canceling?” “Well I’m canceling because the mobile experience isn’t very good.” “Have you tried our app, sir?” “No. Where do I find that?” “Well you find it at FT.com.”

DS: Just to take the mystery out of data: we’re talking specifically about selling renewals and subscriptions and new products. Plus, I assume, data has a role to play in advertising.

RG: It does absolutely, and certainly the targeting that we’re able to often advertise is driven by the data on the inside. Now, to be absolutely clear, we are very very careful that the data we use is anonymous, and so we would target a particular segment by job title, for example, a particular industry sector. But that from an advertiser’s point of view is pure gold, and from a reader’s point of view, well, I would be wary of selling that as a benefit to readers but certainly it’s not particularly intrusive to have ads that are relevant to what you do.

DS: That’s Google’s model.

RG: And it works extremely well. The other crucial area that is important to emphasize is product development. We spend a lot of time looking at the data for how people use the site, and also from generating feedback from focus groups and those sort of things, so that as we put new developments through [an internal] product council and things, those all come with a set of documentation that says, “Actually, on the basis of our insight into the audience, and what readers have been telling us, we think this is the right next thing to do.”

DS: As in, “We need a fastFT.”

RG: Exactly. And without that direct relationship with the reader, you’re kind of guessing about that stuff.

DS: Can you explain your big push into video, which seems difficult, expensive, and not necessarily promising from a revenue point of view?

RG: Video for sure has more challenges than written journalism for a publisher, but there are some important counterpoints to what you’re saying. Firstly, in terms of the cost of producing video, it is coming down and it’s coming down because of changes in technology. Some of our video now is shot on smart phones. I cannot tell the difference when I’m watching that on the screen. There’s the editing process, which can be time-consuming, but even around there, there are models emerging from ourselves and other peers in the industry which use much lighter-touch editing and where we’re getting a much more relaxed about, for example, an individual reporter doing a short piece to smart phone and you just put it straight up on the web with a minimum of editing.

The other important thing is the dynamic in the advertising market. There are big differences between display advertising and video advertising, and actually these differences are quite basic and fundamental.

So to put it in very simple terms, on a single webpage, you can have maybe three big display positions; some other publishers push it further. And you can refresh those display positions, show a new ad every time someone moves to a new page. Given the way that people behave on the web, that’s often once every few seconds [and] that drives the proliferation of display inventory. By contrast, you can only show one video ad per page, and your next opportunity to show a video ad could be three, four minutes away. As a result, the propensity for video inventory to proliferate is much less than display. And the potential supply of ad revenue, if it’s coming from the TV part, which many people think it will do, is almost inexhaustible, for practical purposes. That, we think, is the reason why CPMs [ad prices; cost per thousand views] in the video market are actually holding up much better than anyone expected, and video certainly much better than the display marketplace.

DS: What’s the difference between the CPM rates in video versus display?

RG: The rates in display are now dropping to levels where it’s hardly worth anyone doing it. It is not unusual on exchanges to be able to buy ad across the web for, you know, 50 cents per thousand and less. We are operating in territory of 30, 40, 50 dollar CPM. My head of advertising hates it when I quote CPMs, because inevitably the next meeting he goes to, someone says, “You’re trying to charge me 80 dollar CPM, and your MD said that you trade at 40.” The reality is that the CPM is tailored to the campaign and the particular target audience, so it can vary an awful lot. But we operate in territory which is far above the rest of the marketplace.

DS: And versus FT video, what would the numbers be there?

RG:FT video, we’re doing similar CPMs, slightly higher than our display advertising, but what’s interesting is that our differential over the rest of the marketplace is much smaller than it is in display, so actually the rates for CPMs for video across the marketplace are pretty strong, you’re talking in $20-30 CPMs. It’s not untypical for good quality video programming across the web.

DS: It’s actually good news in some ways.

RG:It’s very good news, because what it means is that publishers are able to turn traffic into revenue.

DS: Last thing is the general question: when we were at a breakfast panel a few years ago, Clay Shirky asked the key question: Basically, to what degree is this applicable, and to what degree isn’t it, to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch or some regional paper. What do you tell the Boston Globe or Charlotte Observer when you visit? Or are many newspapers just past the point of no return?

RG: Firstly, there is nothing to lose, and certainly our experience and New York Times’ experience, the experience of all the titles who are using [paywall] platforms like Press Plus, is subscription is all upside. You don’t lose your advertising revenue. The two things can go together, so why not take that money that’s on the table? And I think there are close to a thousand local and metropolitan titles in the states who have found that now.

DS: But there’s subscription money, and then there’s serious subscription money.

RG: Exactly, and that what is unproven still. My strong belief is that the core of the model, or the core of a successful model, on the web is unique, differentiated content. It doesn’t matter whether that content is finance or business news or general news or local news. If you’ve got something that nobody else has, and there is a group of people who want that, then you have a business. And that something could be great stories about what the local college football team is doing, or so on and so forth. Now the scale of that business is an open question, and we’re yet to see what kind of scale the business can be built on the back of that.

DS: Mostly it’s about what kind of prices you can charge. You talk about scale, you can get a large group of people to come, but can you get hundreds of dollars a year from each?

RG: Those dynamics are very particular to an individual marketplace. But people will pay a lot for things they want. You know, people buy ring tones. The world is different. The publishing industry used to be the gateway. It was the distributor. It was the only way to get the news in a lot of these marketplaces. That role no longer exists, and certainly a publishing business based around republishing and distributing stories, for example, I think simply isn’t viable in a web environment. It isn’t necessary.

DS: Another thing you wonder about with the FT is that because it caters to this global financial elite, not everyone is going to have that market either. I’ve always resisted the idea that financial news was somehow magical, that it exists in some special category, but what do you think about that?

RG: I’ve never bought that as a notion. I think as a niche it has advantages and we probably benefit from that, but the benefit is not as substantial as some commentators made out. And the fact is that within our niche we have an enormous amount of competition, the number of, for example, financial or markets oriented blogs which are pushing out content for free is enormous.

DS: Really, you make it sound easy, and yet it’s not working for most local newspapers in the US, let’s face it.

RG: I don’t want to make it sound easy. Putting in a subs model, I think, is easy and straightforward. I’m not saying it immediately provides the whole solution because as you say, there is an issue of scale, and to sell one sub is not good enough, you need to sell thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands, to sustain the kind of news operations they’ve been used to having. And I do think they have real challenges in that regard because as I say, the part of what they did by acting as distributors for national or international news stories simply doesn’t exist as a necessary role in publishing anymore. The classifieds business, which was a huge part of the way they generated revenue from advertising, has melted away almost entirely and I don’t think it’s coming back.

DS: But they’re basically needing to do what you do; you don’t do classified ads; you sell content to readers. That’s the hope but that’s also the frustration, because it doesn’t seem to be working. Their content isn’t good enough, it’s cut back too far or, I actually don’t know. You tell me.

RG: Ultimately, it does come back to the content. It’s got to be good enough or unique enough for people to want to buy it, and unless those two things are true about it, then actually they won’t succeed either way. They won’t generate the audience they need for advertising, let alone sell a subscription, unless what they’re putting on the page is compelling and attractive to the audience. The subject, I don’t think it matters whether it’s finance or a football team. But it’s got to be something that draws that audience in. It puts much more emphasis on the editorial process and being able to craft something that is attractive.

DS: I guess the last thing is, if you’re trying to sell this idea to an investor, is there an optimistic picture that can be painted with growing margins on the digital side of the business as the print thing falls off and print expenses go down. Is there a story that could be told?

RG: We’re telling a story at the moment. FT’s margins have been improving continuously over the last few years.

DS: Because you’re distributing fewer papers.

RG: Exactly. You know, it reflects the transformation in the business and the fact that actually the digital revenue streams that we’re bringing online are very high margin.

DS: What kind of profit margins?

RG:I don’t think we have quoted margins…

DS: And what kind of margins overall do you quote?

RG: So we are now in high single digits, I think we were 7 percent margins last year. [UPDATE: Actually, the FT Group’s 2013 margins were 12.2 percent; the following sentence basically still holds true:] We are aiming to push that considerably higher this year.

DS: And basically because of the shift to digital it’s cheaper to produce.

RG: Absolutely.

DS: That’s an optimistic note.

Dean Starkman Dean Starkman runs The Audit, CJR’s business section, and is the author of The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism (Columbia University Press, January 2014). Follow Dean on Twitter: @deanstarkman.