The Wall Street Journal‘s new Money & Investing chief, Francesco Guerrera, has an awfully narrow perspective about “Why This Crisis Differs From the 2008 Version.”

First, as an aside, it’s worth noting that The Wall Street Journal is calling this a “crisis.” That’s no small thing.

But this column is problematic. See this:

Starting from the most obvious: The two crises had completely different origins.

The older one spread from the bottom up. It began among over-optimistic home buyers, rose through the Wall Street securitization machine, with more than a little help from credit-rating firms, and ended up infecting the global economy. It was the financial sector’s breakdown that caused the recession.

The current predicament, by contrast, is a top-down affair. Governments around the world, unable to stimulate their economies and get their houses in order, have gradually lost the trust of the business and financial communities.

That, in turn, has caused a sharp reduction in private sector spending and investing, causing a vicious circle that leads to high unemployment and sluggish growth. Markets and banks, in this case, are victims, not perpetrators.

I would argue that it’s not right that these are two crises rather than one long one interrupted by a dead-cat bounce.

But even if you accept the frame, it’s just flat not true that these two crises had completely different origins. The first one, brought on wholly by the financial industry, resulted in a disastrous recession and subsequent increase in governments’ debt, which is what’s largely triggering the current maelstrom (though continued worries about the housing market and our biggest banks are surely key contributors). In the U.S. and UK that increase in debt may wind up being fifty percentage points of GDP—stunning numbers.

You can’t separate the second from the first, which is why historians will surely consider them one event.

Guerrera comes back around to this only to point out that the increase in government debt caused by the first crisis isn’t on the table this time:

The final distinction is a direct consequence of the first two. Given its genesis, the 2008 financial catastrophe had a simple, if painful, solution: Governments had to step in to provide liquidity in droves through low interest rates, bank bailouts and injections of cash into the economy.

A Federal Reserve official at the time called it “shock and awe.” Another summed it up thus: “We will backstop everything.”

The policy didn’t come cheap as governments world-wide poured around $1 trillion into the system. Nor was it fair to the tax-paying citizens who had to pick up the tab for other people’s sins. But it eventually succeeded in avoiding a global Depression.

In other words, the financial industry created the first crisis, which sent governments’ debt-to-GDP ratio soaring, which provoked the second crisis, which is happening in part because governments can’t spend anymore because of the first crisis. But “the two crises had completely different origins”? There’s just no reason to believe we’d be going through this “second” crisis without the first.

And then there’s this, on what supposedly caused the first crisis:

The older one spread from the bottom up. It began among over-optimistic home buyers, rose through the Wall Street securitization machine, with more than a little help from credit-rating firms, and ended up infecting the global economy. It was the financial sector’s breakdown that caused the recession.

If you think the financial crisis started with homebuyers, you’re getting it ass backward, and it’s a real problem. You just can’t get “over-optimistic home buyers” if homebuyers can’t get over-optimistic loans. The Wall Street securitization machine created the bubble by flooding the system with cash. It’s naive—and dangerous—to think that borrowers are going to turn down hundreds of thousands of dollars aggressively marketed to them with the promise that they can cash out in six months because prices are going up. That’s not to relieve borrowers of responsibility, it’s just to acknowledge that lending, particularly in the housing bubble, is an asymmetrical thing—both with information and with power.

This, too, just strikes me as wrong:

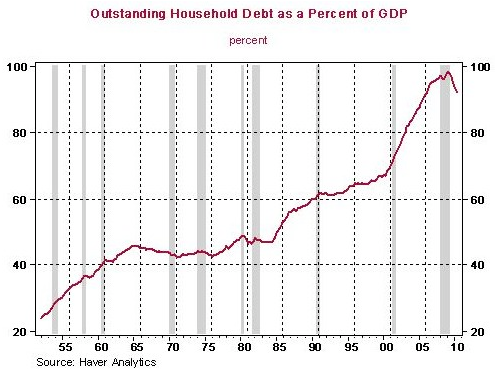

Today, such a response isn’t on the menu. The present strains aren’t caused by a lack of liquidity—U.S. companies, for one, are sitting on record cash piles—or too much leverage. Both corporate and personal balance sheets are no longer bloated with debt.

The real issue is a chronic lack of confidence by financial actors in one another and their governments’ ability to kick-start economic growth.

Personal balance sheets are no longer bloated with debt? Huh?

Narrative matters. It shows us how you see the world, and it helps explain it to others. These two crises are really more like one crisis, and they were both brought on by a financial industry run amok.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.