The native-ad wars have flared up again, this time over Josh Marshall’s Talking Points Memo, the longtime standard bearer for serious, digital-first, for-profit news. TPM has signed up Phrma, the drug-industry lobby, to sponsor its Idealab Impact section, a deal that includes running Phrma-written pieces as native ads.

There’s nothing inherently worse about an advertiser using a thousand words in story form to spread its message than there is with an ad that uses 30 words, an idealized photo, and a catchline to do the same.

So if we accept that advertising itself is a necessary evil, the only question for native ads is whether they’re clearly presented as advertisements and not editorial.

As Dean Starkman has written, that presents an existential problem for native ads: Make them too native and they deceive readers. Make them too non-native and few will read them.

Marshall, though, sees something of a third way:

Why are these “Sponsored Messages” attractive to advertisers, particularly our advertisers? Because our advertisers are policy focused and thus tend to have more complex arguments. They’re not just selling soap or peanut butter. There’s only so much of those arguments you can fit into a picture box or a video. They want room to make fuller arguments, lengthier descriptions of who they are and what they do, as you would if you were writing an editorial – in text, going into detail. The opportunity to do that to an audience like TPM’s is of particular value because you’re people who care about policy and you read stuff.

I don’t see anything in this that’s inherently different than a regular ad, which also tries to get across its message to readers, often via propaganda:

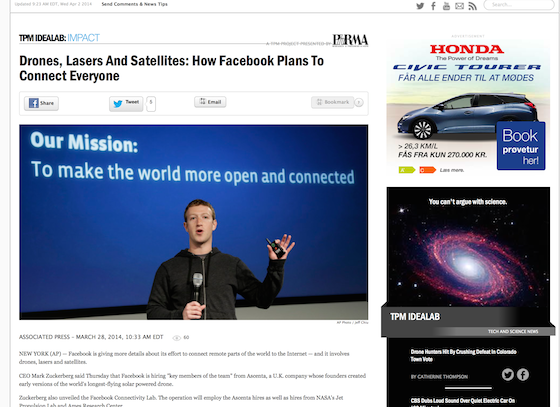

So it comes down to execution. Here’s what TPM’s non-ad Idealab Impact stories look like:

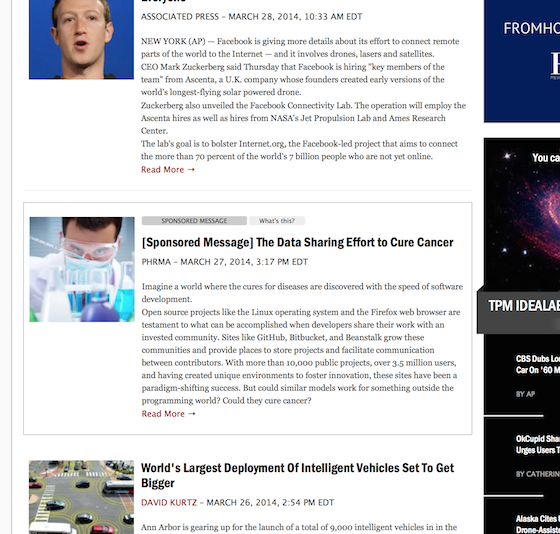

Here’s what the landing page looks like with Phrma’s native ads mixed in:

And here’s Phrma’s actual sponsored post:

TPM doesn’t cross any lines with its native ads, but it walks closer to them than, say, The New York Times and Wall Street Journal did with theirs.

The NYT, for instance, put a bright colored border around its Dell native ad, put the Dell logo on the byline, used a different, smaller font, and blocked Google’s spiders from indexing it.

TPM’s distinctions are subtler: A thin border, a byline that says PHRMA in regular text, an easily missed “SPONSORED MESSAGE” disclosure atop the post, a centered layout, the same font. Most people are going to know this is an ad, but it’s conceivable that at least some will not.

That doesn’t mean you throw out the baby with the bathwater. Just make these signals much clearer.

Andrew Sullivan isn’t having any of that:

My concern with “sponsored content” in vast swathes of online media – from the New York Times to Time Inc. and Buzzfeed – is simply that, by deliberately blurring the distinction between advertising and editorial, it must necessarily undermine this integrity and cast a doubt over that trust. It violates the core integrity of any journalistic institution to treat the prose of commercial interests as the equivalent of the prose of editors and writers – or to blur the lines between the two, by presenting commercial speech in extremely similar formats to editorial speech.

Am I being too purist? All I can say is that my position was once held by every journalistic institution you can think of only a few years ago. Back then, advertising was a revenue model that was self-explanatory, clearly differentiated from any article, and if it could in any way be confused with an article would have the word “Advertisement” attached to it.

Here’s the thing: Native ads are just advertorials by another name, and advertorials have long been published by news organizations of the highest standards, including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Yorker. Those “special advertising sections” are the native ads of print, and they’ve been there for decades.

Does anybody read them? You have to assume somebody does or advertisers wouldn’t keep paying for them.

Journalists may not like to think it, but advertising is part of a publication’s content. Lots of people buy the Sunday paper for the coupons. Some still buy papers for the classifieds. They buy Vogue for the ads. And some people read the special advertising section.

In a perfect world, journalism would be paid for entirely by readers and publications’ interests would align with them and them alone. But while Andrew Sullivan and Consumer Reports can make a go of that, 99.9 percent of journalists and their organizations cannot.

And so in this fallen world, we have advertising, which is potentially corrupting in all its forms, not just in advertorial ones.

The much more dangerous aspect of advertising is the self-editing or outright censorship big advertisers can prompt on the news side. If TPM becomes heavily reliant on pharmaceutical ad dollars, will it be able to cover pharma issues without pulling back? I’d like to think so. The most famous case in business journalism was when The Wall Street Journal‘s legendary editor Barney Kilgore faced down General Motors after the carmaker withdrew its huge account in protest of WSJ coverage. But we know from history that this is not always the case.

Tobacco companies’ products killed 100 million people in the 20th century, most of them after scientists proved they caused mortal diseases. Marketers and the media played critical roles in creating and passing on the propaganda that allowed cigarette companies to addict millions of new customers a year.

Journalism was so addicted to tobacco advertising that the press at least sometimes censored itself when covering the cigarette companies.

The New Republic, for instance, a few years before Sullivan got there, squashed an investigation on Big Tobacco’s insidious media strategy because Marty Peretz foresaw “massive losses of advertising income.”

Time, also around the same time in the 1980s, deleted anti-tobacco references from an advertorial pushing healthy living, and a spokesman actually said this to the Chicago Tribune:

`Time, as does Newsweek, has a lot of cigarette advertising. Do you carry material that`s insulting to the advertiser?“

And that was when the media was minting money. With the press now in a far weaker position, the temptation to self-edit is surely stronger. That’s potentially a far bigger problem than native advertising, particularly when the latter is well disclosed.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.