The Wall Street Journal‘s A1 story today on how bureacratic red tape has slowed the stimulus has a pretty big hole in it, and that’s too bad. It could have been better.

Here it is:

But when Obama administration officials were selling the idea of a huge federal stimulus program to buoy the U.S. economy, they talked about a plan that would get money into the economy quickly. Instead, spending stimulus dollars fast has turned out to be surprisingly hard.

But that’s not really true. The plan all along was to phase in the spending over three or four years, not to spend it all at once. The WSJ doesn’t make note of that—and that undermines the premise of its story, which could have been interesting. Here’s what it does say:

The third element was around $230 billion in funding for infrastructure projects ranging from road repaving to modernizing the electric grid. This was to be the most visible element of the job creation effort. Federal agencies have designated recipients for around 80% of the funds, but paid out only about a third of them to date.

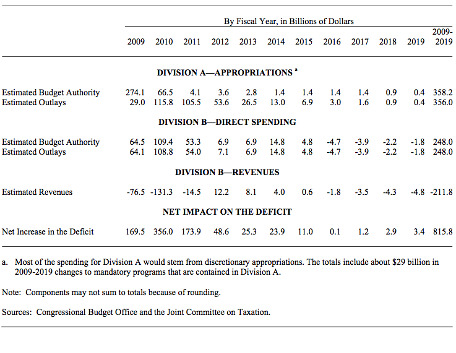

But here’s the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office’s estimate from January 2009 of when the stimulus money would be spent:

The relevant section is “Divison A-Appropriations.” About $145 billion of that (which is mostly infrastructure spending), was slated to go out last year and this year. Another $211 billion was to go out after this year. In other words 41 percent was supposed to be out by the end of this year. The Journal says about 33 percent is out. There are still three-and-a-half months left in the year. That doesn’t look so delayed now does it?

Naturally, the Journal is on to the red tape angle here to explain why the supposedly surprising (but not really) slowness in spending. That red tape is a legitimate, serious story, but not when it’s used to back up a false frame.

The real story—or a better one, anyway—would have been why the Obama administration and Democrats in Congress didn’t frontload more of the spending in 2009 and 2010. It’s well established that they, foolishly, underestimated the seriousness of the recession they inherited, and which already had been underway for more than a year. That’s allowed disingenous opponents to claim that the stimulus spending didn’t do anything at all or made matters worse, when it actually created or saved hundreds of billions of dollars in GDP and put or kept up to three million people to work (That’s backed up by the known longhairs at Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan Chase). Leave aside the question of whether the stimulus should have been bigger: and ask why it wasn’t done differently.

Why was it spread out over so many years? Why was “Franklin Delano Roosevelt was able to create the Civil Works Administration in a lunchtime meeting and watch four million people go to work in the next four months on roads, schools, parks and airports,” as the Journal points out. Surely no small part of it was the bureacracy’s understanding of how long it takes to get through the bureacracy. Like this:

The state Department of Human Services and the Detroit agency exchanged several versions of Detroit’s advertisement before its language was approved. It was January 2010, more than a year after the first advertisement had gone out, before the Detroit agency had a new one to post.

It was another two months before the city awarded contracts. Detroit weatherized its first home using stimulus dollars in March 2010.

Every day that these stimulus funds spend or spent parked in the Treasury is another day that lots of somebodies out there don’t have work. That’s still true today.

Robert Shiller pointed out in an undernoticed New York Times op-ed a couple of months ago that the stimulus cost so much per job because it was capital-intensive work. He noted that the government could create one million jobs paying $30,000 for $30 billion. There are currently about 15 million people out of work. To be crude about it (obviously, it’s much more complicated than this), you could employ them all for $450 billion, or not much more than half of what the stimulus cost. Shiller:

Two friends of mine, both economists, came upon a stimulus project recently that illustrated the problem. On a Wyoming highway they saw a sign that read “Putting America to Work: Project Funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act” and prominently featured a picture of a worker digging with a shovel. Out on the road, there was plenty of equipment, including a gigantic asphalt paver, dump trucks, rollers and service vehicles. But there wasn’t a single laborer with a shovel. That project employed capital, certainly, but not many human beings.

And:

So here’s a proposal: Why not use government policy to directly create jobs — labor-intensive service jobs in fields like education, public health and safety, urban infrastructure maintenance, youth programs, elder care, conservation, arts and letters, and scientific research?…

Big new programs to create jobs need not be expensive. Suppose the cost of hiring a single employee were as high as $30,000 a year, several times typical AmeriCorps living allowances. Hiring a million people would cost $30 billion a year. That’s only 4 percent of the entire federal stimulus program, and 0.2 percent of the national debt.

Why don’t we just do it?

I think you might find the answer to that from Jon Stewart, who recently told New York that “Obama ran as a visionary and leads as a legislator.”

But how long would it take to ramp up a program to pay people to clean up parks, document the country, paint roofs white, tutor kids, plant trees, help nonprofits (including churches), or other non-capital-intensive work? I suspect the answer would be seriously depressing.

And that’s a real story.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.