A group of middle school students at Brooklyn’s Urban Assembly Academy of Arts and Letters got a special treat one March afternoon in 2011. Just five weeks after the announcement of the $315 million deal in which AOL acquired The Huffington Post, AOL’s chief executive, Tim Armstrong, and Arianna Huffington, HuffPost’s co-founder, came to the school to teach a class in journalism.

A group of middle school students at Brooklyn’s Urban Assembly Academy of Arts and Letters got a special treat one March afternoon in 2011. Just five weeks after the announcement of the $315 million deal in which AOL acquired The Huffington Post, AOL’s chief executive, Tim Armstrong, and Arianna Huffington, HuffPost’s co-founder, came to the school to teach a class in journalism.

The lesson—or what one could see of it in the short, treacly video account that ran on The Huffington Post—may have told more about the future of the news business than what either Huffington or Armstrong intended. A few moments after the video begins, an official of the program that arranged the visit speaks to the camera: “We are delighted that Arianna Huffington and Tim Armstrong are going to be teaching a lesson on journalism!” What the video showed, though, wasn’t a lesson in how to cover a city council meeting, or how to write on deadline. Instead, the teachers in the classroom told her students, “We’re going to give you headlines that we pulled from newspapers all over the place, and you guys are going to place them and decide what type of news they are.”

This, then, was a lesson in aggregation—the technique that built Huffington’s site up to the point that AOL wanted to buy it.

In just six years, Huffington has built her site from an idea into a real competitor—at least in the size of its audience—with The New York Times. The Huffington Post has mastered and fine-tuned not just aggregation, but also social media, comments from readers, and most of all, a sense of what its public wants. In the process, Huffington has helped media companies, new and old, understand the appeal of aggregation: its ability to give prominence to otherwise unheard voices and to bring together and serve intensely engaged audiences, as well its minimal costs compared to what’s incurred in the traditionally laborious task of gathering original content.

HuffPost’s model has provoked sharp criticism from, among others, Bill Keller, executive editor of The New York Times, who, like Captain Renault in Casablanca, appears shocked that aggregation is going on. “Too often it amounts to taking words written by other people, packaging them on your own website and harvesting revenue that might otherwise be directed to the originators of the material,” Keller wrote. “In Somalia this would be called piracy. In the mediasphere, it is a respected business model.” He wrote this even as the Times’s own site has demonstrated the power of aggregation in many ways, notably in a blog called The Lede, which has deftly captured the tempo and texture of such ongoing stories as the protests in Iran and the upheaval in Egypt by blending Times reporting with wire reports and original material from outside sources.

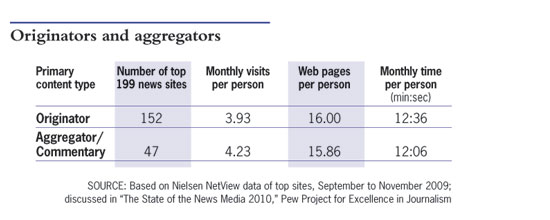

In fact, almost all online news sites practice some form of aggregation, by linking to material that appears elsewhere, or acknowledging stories that were first reported in other outlets. An analysis of 199 leading news sites by the Pew Project for Excellence in Journalism found that most of them published some combination of original reporting, aggregation, and commentary and that the mix differed considerably depending on the management strategy, the site’s history, and—to be sure—its budget.

Pew categorized forty-seven of the sites it surveyed as aggregators/commentators and 152 as primarily producers of original content. In the aggregator/commentary group, four-fifths of the sites were online-only; of the original-content group, four-fifths were connected to traditional media. Traffic is highly concentrated at the top of the list, with the top ten sites accruing about 22 percent of total market share. Seven of the top ten sites are “originators.”

What is surprising is that consumers use these different kinds of sites quite similarly. Original-content sites do marginally better at keeping visitors for longer stretches and leading them to more web pages, but it is hard to imagine that this slightly higher engagement is enough to help cover the costs of original production and reporting.

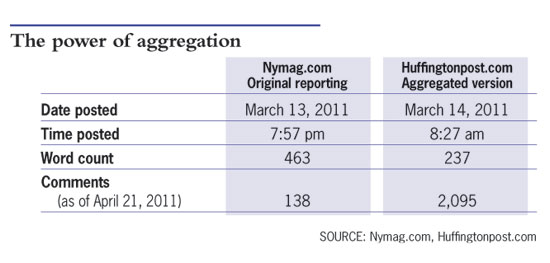

Huffington often says that aggregation benefits original-content producers as much as it does the aggregators. The story of a recent blog post on New York magazine’s site makes for a good illustration.

At about the time that Huffington and Armstrong were visiting the school in Brooklyn, Gabriel Sherman, a contributing editor to New York, was nailing down a scoop. Under the headline “Going Rogue on Ailes Could Leave Palin on Thin Ice,” Sherman reported that Roger Ailes, the head of Fox News, had warned his paid commentator, former Alaska governor Sarah Palin, not to go forward with her video accusing the media of “blood libel” in the way they portrayed conservatives after the shooting of Arizona representative Gabrielle Giffords.

The story required at least three days of reporting and editing work. The facts had to be bulletproof. The post went live on nymag.com’s Daily Intel column at 7:57 p.m. on March 13.

The next morning, an editor for the Huffington Post spotted the item and wrote a rendition of it for that site, publishing at 8:27 a.m. Huffington Post played by the rules: It credited Sherman by name and gave nymag.com a link at both the beginning and the end of the item. What Huffington Post took from Sherman’s post—237 words, or about half the original length—would be justifiable under almost any definition of copyright.

The power of aggregation soon became clear: The original Sherman post drew nearly 53,000 readers on nymag.com, and about 17,500 of them came directly from the links on Huffington Post. Smaller numbers of readers came from hotair.com, which is part of a network of conservative websites and publications; and from Andrew Sullivan’s popular blog, The Daily Dish. All told, three-fourths of the traffic to Sherman’s story came from other sites. The item also drew more than 130 reader comments on nymag.com, which is far higher than what the typical blog post gets.

The real winner, though, was Huffington Post. Its aggregated version of the item got more than 2,000 comments. Comments are not a perfect proxy for traffic, but it appears that the Huffington Post item got a much bigger audience for its post than the original New York item, for a fraction of the cost.

As this example shows, links from other sites or search engines are among the cheapest and most efficient ways to bring in new users. Even the largest news suppliers, such as Time.com or CNN.com, appreciate what top billing on YouTube or Google News can do to increase traffic and advertising revenue. “There are ways you can deliver better ad results, but you can’t do it if you focus on your own content only and not others,” Scout Analytics vice president Matt Shanahan says. He adds that when sites promote each others’ content, they create more engaged audiences through additional page views and commentary. “The advertiser wants the audience,” he says. “And the audience wants the audience.”

News organizations have always blended material from a variety of sources by combining editorial content from staff, news services, and freelancers; adding advertising; and then distributing the package to consumers. In the digital world, news aggregation is not so different. It involves taking information from multiple sources and displaying it in a readable format in a single place. Digital aggregation businesses can be successful when they provide instant access to content from other sources, and they generate value by bringing content to consumers efficiently.

The cheapest way to aggregate news is through code and algorithms, with little or no human intervention. The way an individual story is displayed throughout the day is determined automatically, typically according to how recently the article was published and how popular it becomes. Aggregation is slower and more expensive when it becomes “curation,” involving humans in the filtering and display processes.

Google News belongs to the most basic aggregation category, called “feed” aggregation, in which an algorithm sorts news by source, topic, or story and displays the headline, a link and sometimes a few lines from the original story. The costs are low.

Yahoo News is an enhanced aggregation feed; it has always had some level of editorial management in the selection and placement of stories—though it posts up to 8,000 stories a day, so editorial involvement is fairly minimal. Like Google News, Yahoo News aggregates from across the web, but it gives preference to the approximately 200 media companies from which it licenses content—such as the Associated Press, Reuters, and ABC News. In return for the content, Yahoo News gives the partners a share of its ad revenue—in addition to sending them traffic.

Traffic to the news sections of Yahoo and Google is relatively small compared with the total traffic of these companies’ sites. For example, in one week in April 2011, Yahoo News represented about 6.5 percent of the total traffic to all Yahoo sites as determined by the online audience measurement company Hitwise. But Google News and Yahoo News are the first stop of the day for significant numbers of users, and that is considered a good predictor of multiple visits and customer loyalty. Yahoo and Google also let individual users customize their home pages by personal preferences—according to topic or news source. In the latest refinements, Yahoo has introduced a recommendation engine for stories called LiveStand, while Google introduced “News for You,” which keeps track of what stories a user has clicked on and provides related content.

Large media companies such as The New York Times and The Washington Post and independent companies like Flipboard are doing much the same thing—developing programs that can recommend stories and videos based on a user’s previous choices. Because of the wide variety of topics and the enormous volume of stories posted, this is a far more difficult problem than creating the algorithms that Amazon or Netflix use for recommendations. Some companies are also working on adding friends’ and networks’ reading choices to the recommendation engine.

On the other end of the spectrum, Huffington Post starts with algorithmic selections but puts them into the hands of human editors who set priorities for sections and then condense, rewrite, or bring several organizations’ versions of the same story together. HuffPost turbocharges the formula with a mix of social media, dynamic packaging, and photos and charts. These techniques lead to praise, criticism—and parody. Comedy Central’s Stephen Colbert told viewers that, to retaliate for HuffPost’s republishing without permission the entire contents of his show’s website, he would create “The Colbuffington Repost,” that is, the entire Huffington Post, just renamed. Its re-re-packaged content would make him the owner of the “Russian nesting dolls of intellectual theft.”

Newser.com, the aggregation site co-founded by Michael Wolff, represents much of what legacy media companies hate about the web: It has little original reporting, and its stories are short rewrites of information from several other sites, with a design that emphasizes graphics. Wolff, a media critic who is now editor of Adweek, has spent much of his career playing provocateur—and driving people in the media business a little crazy. This effort is no different. Andrew Leonard, a writer for Salon, wrote a story called “If the Web doesn’t kill journalism, Michael Wolff will.” Leonard says that Newser displays a “truly precious degree of shamelessness.… Even the slide shows are repackaged, rewritten and abbreviated versions of content originated by other publications.”

Newser says out loud in its slogan what many aggregation sites hope their users will infer: “Read Less, Know More.” Its co-founder and executive chairman, Patrick Spain, says the site aims to limit its stories to 120 words. “The most time-consuming part of editorial is identifying which stories we are going to carry,” he says. “And we have to identify the one, two, or three major sources to use to write the story.” Wolff asks, “If you are a consumer, why would you go to a single source?” The New York Times, he says, “used to be seen as a broad view of the news” but is now regarded as “parochial and limited.” Newser publishes about sixty stories, or digests of stories, per day, though it has at times published as many as 100. “Cost is less of a driver than the affect we are looking for,” says Spain. “If you have hundreds of articles, it is not an editorial function; it is a fire hose function.”

Newser has business offices in New York and Chicago, but its writers are freelancers. They live in the U.S., Europe, and Asia, and generally work from home. There are four full-time and about fifteen part-time staff members who perform editorial duties, working at rates of $20 to $40 per hour. Spain says “this is a gigantic edit staff compared to Digg” (a site where story placement depends on readers’ votes). “They have no editorial people. But this is tiny compared to The New York Times.”

For its other functions, Newser has eight full-time employees who work on marketing, administration and management, and technology. Its total operating costs are about $1.5 million per year, for a site with 2.5 million unique visitors a month. Spain and Wolff have both said that in 2011 they expect to break even—that is, to get to the point where advertising revenue is high enough to cover operating costs, though not to start paying back the initial investors.

Nymag.com does original reporting, as in the case of the Ailes/Palin story, but since 2007 it has also had a strategy of growing through four blogs that use third-party content combined with original reporting: Grub Street (on food), Daily Intel (political and media news), Vulture (culture), and The Cut (fashion). “These niches need editorial authority to be successful,” said Michael Silberman, general manager of nymag.com. In a given week, the site publishes only about thirty-five articles from the print magazine but 450 to 500 blog posts and thousands of photos. As a result, only 14 percent of the site’s page views are of content from the magazine. “Every time we increase the frequency of the blog posts, we can drive up the numbers of audience,” Silberman says. And since 2007, nymag.com’s audience has grown from 3 million unique users to 9 million.

The site has been particularly adept at going beyond its local roots. About 30 percent of the print magazine’s audience comes from outside New York, but 70 percent of the website’s readers live beyond the home market, which helps the site attract national advertising. Its restaurant section, Grub Street, expanded in 2009 and is now in six cities.

The evolution of nymag.com’s cultural news site, Vulture, from a small feature to a destination with 2.5 million unique users demonstrates how powerful aggregation strategies can be. When it started in February 2010, Vulture was getting 700 to 800 unique visitors daily. After its official launch in September 2010, Silberman found that it “filled an editorial hole in the marketplace.” One of its most popular features is “clickables”—a stream of twenty short posts per day, featuring, among other things, viral videos and music albums leaked ahead of official release. Vulture now has ten full-time editorial employees and get lots of support from New York magazine back-office departments in finance, human resources, and technology. The magazine has decided to spin off Vulture as its own site with a separate web address sometime in 2011—a move that Silberman believes will help generate sales of entertainment and other national ads to companies that feel that a close tie to New York City can be an impediment.

There are few secrets on the Internet, and even fewer barriers to entry. Each innovation that works instantly attracts imitators and improvers. (LinkedIn, the professional networking site, launched LinkedIn Today in March 2011 to curate content not just by topic but also by what people in a user’s network or industry are reading.) Because aggregation is so much cheaper than original content, it has an automatic economic advantage, but the attractiveness of aggregation brings more and more competitors into the field. So merely being an aggregator is hardly a guarantee of economic security.

A few publishers have successfully sued sites that steal their content outright. That has led others to toy with the idea of getting news sites to unite and deny aggregators access to their content. Even if that kind of cooperation were legal—and it might not be—it would be impossible to sustain or enforce. There are just too many sites producing original content. The economic benefits of aggregation and being aggregated are significant, even if they differ widely from one site to the next.

To continue to Chapter Seven, click here.

To download this chapter as a PDF, click here.

Bill Grueskin, Ava Seave, and Lucas Graves are the co-authors of “The Story so Far: What We Know About the Business of Digital Journalism.” Grueskin is dean of academic affairs at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Seave is a principal of Quantum Media, a NYC-based consulting firm. Graves is a PhD candidate in communications at Columbia University. For further biographical details, click here.