Last week we learned that Egypt only has four major ISPs, making it relatively easy for the government to shut off the Internet with just a few phone calls. For those who are able to get online on Egypt—either through dial-up connection or via Noor Data Networks, the ISP that supports the country’s stock exchange and remains online—users still have to evade the censors.*

Meanwhile, the situation in Egypt has highlighted the problem of Internet censorship by various governments elsewhere. The Wall Street Journal reports that Chinese authorities have blocked the word “Egypt” from microblogging sites, and, according to Reuters, Iran’s regime is restricting access to major news websites.

Mashable’s Vadim Lavrusik explained several ways Egyptians were still able to get online and communicate freely—if slowly—including: third-party social media applications (like HootSuite or TweetDeck, for instance), ad-supported proxy sites located in other countries, and virtual private networks that mask the origin of the Internet user’s requests. Lavrusik lists another increasingly popular, and increasingly vital, way to evade the blockage: free encryption services like Hotspot Shield or Tor.

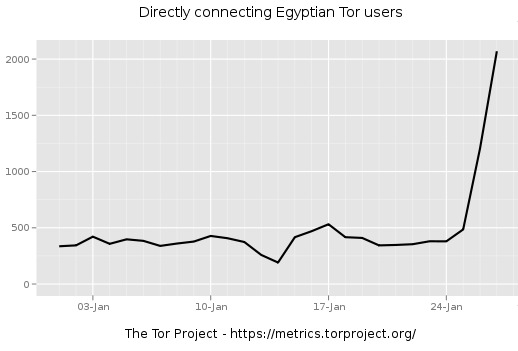

ReadWriteWeb reported that Egyptians’ use of Tor was “skyrocketing” last week. According to a report on public radio station WBUR today, over half a million people in Egypt downloaded the Tor software before the government shut down the country’s Internet. Graph courtesy ReadWriteWeb and the Tor Metrics Portal:

Tor is a system of software and computers, anonymously hooked into a network, which allows people to keep Internet activity private and secure by hiding their location and other indentifying information. Each transaction with a website, e-mail service, or social media network that a user makes is distributed among several different connections, relayed back and forth between several different computers in the network, so the traffic is harder to track.

More specifically, Tor establishes a random, circuitous route for each online connection to take (passing through at least three servers), keeps it open for about ten minutes, and then refreshes it and creates a new one. As Tor’s website explains:

Tor helps to reduce the risks of both simple and sophisticated traffic analysis by distributing your transactions over several places on the Internet, so no single point can link you to your destination. The idea is similar to using a twisty, hard-to-follow route in order to throw off somebody who is tailing you — and then periodically erasing your footprints.

[…]

Tor does not modify, or even know, what you are sending into it. It merely relays your traffic, completely encrypted through the Tor network and has it pop out somewhere else in the world, completely intact.

This network method, called “Onion routing,” was first developed for secure communications in the U.S. Navy. It’s still used by the military in certain places in the Middle East, and it’s also used by journalists and NGOs to communicate privately with whistleblowers and field workers.

A blog post on the Tor Project website over the weekend makes an important caveat to Internet users in Egypt: that it is impossible to guarantee complete anonymity to those who decide to use the service. Egyptian authorities are working aggressively to track—and arrest—political activists, and no ecryption system is fool-proof. But, the post continutes,

Please understand that while we make no promises, we believe that Tor is currently the best option for people in this situation. It’s what we use when we’re in Egypt and it’s what we think will serve people the best in Egypt when they have a network connection to the rest of the internet.

The more people who volunteer their computers to become part of the network, of course, the more anonymous each member will be. Visit the Tor website to find out how you can volunteer to help the project by donating bandwidth and becoming part of the network. Several hundred thousand people are already participating, and big events like the Egyptian revolution continue to bring attention to it.

Even though it would be next to impossible, for various logistical and legal reasons, for a similar “Internet kill switch” to be enacted in the U.S., that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be thinking about these things now. With a system like Tor, we can use the freedom we have here online to help those who need it elsewhere. When a crisis erupts somewhere in the world, we often wonder what we can do to help. (There’s a flood—should we donate money? There’s an earthquake—should we donate blood?) Now we should ask the question: there’s a regime suppressing its people’s rights to free speech and open communication—should we donate bandwidth?

*[Update: Several hours after this post was published, on Thursday evening, news broke that Noor Group, the last ISP remaining online in Egypt, had also gone offline. But dial-up service was still available; more detailed information here.]

Lauren Kirchner is a freelance writer covering digital security for CJR. Find her on Twitter at @lkirchner