CJR has been accused of crankiness for our early critique of Rupert Murdoch’s new iPad newspaper, The Daily. The Poynter Institute’s Damon Kiesow characterized our commentary as a dismissal of the new medium, similar to early complaints about the colorful, non-traditional USA Today in the 1980s. But while we felt unsatisfied by the actual content of The Daily—it felt thin, stale and outdated in proportion to the publication’s impressive staff hires—the fact remains that, with The Daily, News Corp. has set the bar for all future tablet publications. Whether that bar has been set high enough is the subject of several other posts. Even if only for the large amount of money and publicity surrounding this project, it is an important step in establishing iPad users’ expectations for what a news app should look like.

But it’s only a first step. If the trajectory of the Web has taught us anything, it’s that technology will change so quickly that we have no idea what tablet publishing will look like (and sound like, and feel like) in a year, or five, or ten. Fifteen years is not a long time in the history of man, but it’s light years in the history of publishing and reading. When Salon and Slate launched in 1995 and 1996, respectively, the Internet was so wide open and undefined that the right language didn’t even exist to talk about it yet. (Note: I spoke with some of the people involved in the first days of Slate and Salon and asked them to reminisce about the state of publishing at that time. The Daily was not a focus of those conversations, and so all conclusions and connections drawn are my own.)

When Salon launched its first issue in November 1995, there was no real model to look at and say “this is what a news website should be.” Co-founder Laura Miller says she remembers online entities Feed and Word, neither of which exist anymore. For the Salon writers and editors, the only model, obviously, was print. Miller remembers bringing a yellow legal pad and pen to that first editorial meeting and trying to block out a design for the website. “I still have all those weird little sketches with boxes and arrows from when we were trying to figure out what we were doing,” she says.

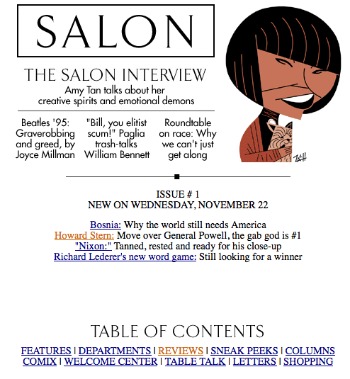

Here’s a screen shot of the inaugural issue, which you can still read, here:

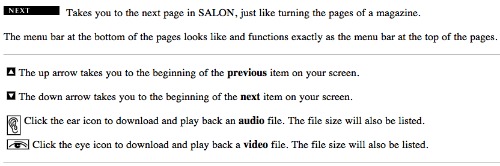

The first issue was simple, by design: readers new to Salon were often new to the web, as well. It made sense to re-create the look of a print magazine so readers wouldn’t be disoriented. Early issues included a “How to Use Salon” tutorial page, which introduced readers to the navigation bar, up and down arrows, and audio/visual features:

Certain web-friendly features took hold in time, the early zygotes of what are now established online conventions. Salon’s “Table Talk” section, for instance, was a community-building effort that linked from articles to discussion forums, before there were comment sections.

Salon’s publishing schedule, too, initially reflected a print one; a whole new issue would appear every week, complete with cover art. That rigidity, of course, did not last. As Scott Rosenberg, another Salon co-founder, writes in an e-mail: “The single biggest mental shift we had to make—and it became obvious almost instantaneously—was to move from the ‘issue’ model of print to the ‘wheneverly’ periodicity of the Web. It took us forever—at least five years—to achieve what we called, in those days, ‘continuous publishing.’”

“Every single thing that is taken for granted about web publication, we had to learn as we went along,” says Miller.

Michael Kinsley, now an opinion columnist for Politico, launched the first issue of Slate in 1996, and he laughs when he remembers how new and strange everything felt at the time. “I thought—and this shows either how early it was, or how out of it I was—I thought the idea would be that we would put together a magazine, approximately the size of The New Republic, and once a week, people would go there and print it out,” he says. “I may have gotten as far as thinking that we would send them an e-mail with a link in it, to print it out, but you know, it took a few weeks on the job for me to see that that was not the point.”

While the well-established conventions of print publication didn’t really apply, new conventions for the web had not yet been established, either. Everything was up for debate, even the page orientation. Would a reader, being used to reading left to right, object to moving a page up and down? Where do the page numbers go? The pull quotes? How long should a page be before you had to click?

“We had long theological arguments about scrolling versus clicking,” Kinsley says. “We were still stuck in the mindset of a traditional magazine…. When we gave that up, it was anarchy.” As he wrote in his editor’s note in the first issue (which is very interesting; please read it in full):

SLATE is not the first ‘webzine,’ but everyone in this nascent business is still struggling with some pretty basic issues. Starting an online magazine is like starting a traditional paper magazine by asking: ‘OK, you chop down the trees. Then what?’

Here’s a screenshot from mid-1999 (the earliest the Wayback Machine archive will take us), minus some missing artwork:

Besides the design elements, online publishing presented a whole new world of business models, as well. Miller remembers the outrage that erupted when Borders announced their sponsorship of Salon’s book review page, putting an ad on top and providing “Buy this book” links under each review—a partnership that is now quite commonplace, but which then seemed to some readers to be crossing a sacred line.

When Slate launched, it did so with the promise that a paywall would go up within a few months. When it finally did, Slate charged $19.95, for which subscribers got a year of access and a Slate umbrella. It wasn’t a disaster—Kinsley said about 30,000 people subscribed—but ultimately the Slate team decided to take the wall down after about eleven months, and the site has been free ever since. But that’s okay, says Kinsley; the paywall was an experiment, and it didn’t work out. “By the nature of experiments, if you’re not prepared for it to work out, then you shouldn’t be doing it,” he says.

Kinsley notes, though, that through all of their experimentation, what hasn’t changed at Slate is its editorial voice, the overall vision. (That, and its very particular shade of plum.) Miller says the same thing about Salon: that the consistent focus has always been the content, rather than the technological possibilities of the web. Although they were publishing in a new medium, the attraction of the medium wasn’t the potential of that new technology—because, of course, the technology wasn’t very good at the time. It took three servers just to upload an article. A digital video, had there been such a thing, would have probably broken the Internet.

According to Miller and Rosenberg, Salon began as an online venture rather than a print one because it was easier: easier to publish what they wanted, and easier to raise money for it. The dot-com boom was in the upswing, and investors were eager to help people play around and test what the web could do. For Salon’s writers, it was a new way to disseminate their writing, outside of the existing print publication world. “There was just all this built-up stuff that people wanted to say,” Miller says. The way that stuff looked, and all the different ways readers could access it and interact with it—that could wait.

The Slate founders, in fact, tried very hard to emphasize that the medium was not the point. Kinsley says that because they were among the first publications to go online, many readers assumed they were a technology magazine, that they were “about” the Internet. For that reason, they purposefully didn’t have a “Tech” section on Slate—something that has obviously changed in the years since. Kinsley’s introductory essay, excerpted above, ends with this:

Finally, we intend to take a fairly skeptical stance toward the romance and rapidly escalating vanity of cyberspace. We do not start out with the smug assumption that the Internet changes the nature of human thought, or that all the restraints that society imposes on individuals in “real life” must melt away in cyberia. There is a deadening conformity in the hipness of cyberspace culture in which we don’t intend to participate. Part of our mission at SLATE will be trying to bring cyberspace down to earth.

When asked about that passage this week, Kinsley laughs. “That enraged people,” he says. “The romance of the Internet was almost unbearable. But it’s still true today, it’s become true again. I’m still proud of that…. And I hope Slate is still skeptical.”

We can’t know what the publishing world—and the reader experience—will be like fifteen years from now. The Daily’s layout still looks like a glossy magazine, with mini-websites embedded in each page. It still takes its cues from print and the Web, starting simple, just as Salon and Slate did in the mid-1990s. That’s one step in a long evolution.

Will The Daily be around in fifteen years? No idea. A strong editorial vision and compelling content would help. Barring that, they’ve got the money to keep on experimenting and stretching the form, so it will be interesting to watch. But it bears mentioning that design and formal experimentation weren’t what established Salon’s and Slate’s distinctive, name-brand recognition among readers. “Being first” didn’t, either—plenty of other publications from their era have disappeared. It’s always been more about what they said than how they looked, even as the way they look has gone through such dramatic change. The Daily is the first big splash in tablet news, but it’s only the first of many. Developing a voice of its own—and content readers can’t get anywhere else—will be just as important for The Daily as developing the way it’s delivered.

Lauren Kirchner is a freelance writer covering digital security for CJR. Find her on Twitter at @lkirchner