The New Museum’s latest exhibit “The Last Newspaper” is a misnomer, a slightly disjointed jumble of artworks that appropriate newsprint in varying degrees of relevancy and coherency. The pieces on display there, says the exhibit’s introduction, “use the newspaper as a platform to address issues of hierarchy, attribution, contextualization, and editorial bias. By disassembling and recontextualizing elements of the newspaper…the artists on view take charge of and remake the flow of information that defines our perception of the world.” I’m not sure what I expected when I went: I suppose that because of its title, I thought I would see art about the news, rather than art about politics that happened to use newsprint as a raw material.

Most of the pieces in the collection make their message merely by pointing out the jarring juxtapositions inherent in Western media. For instance, Rachel Harrison’s trio of framed newspaper pages in which full-page ads for a Sotheby’s MasterCard sit opposite articles about truck bombings in Baghdad and the amputee victims of fighting in Gaza. Or a cluster of mannequins wearing Thomas Hirschhorn’s couture-looking gowns whose fabric is printed with horrible photographs of torture at Guantanamo. Good points, but not anything too original there in terms of media criticism. Or perhaps there are just a few too many pieces like that in the exhibit for their message to feel fresh.

(All photographs by Lauren Kirchner)

That said, points for originality go to Dash Snow, who collected several years of New York Post and Daily News front pages featuring Saddam Hussein, and then covered them with semen and multicolored glitter. The plaque on the wall beside this series tells us that “each page is a response to the hysterical headline and a comment on the brutally transient nature of celebrity.” Another surprising piece, not on display on the day I visited but described in this New York Times review, is an enactment of the William Pope.L. performance piece in which a team of people wearing Barack Obama masks circled the visitors while eating small pieces of a Wall Street Journal. Sorry I missed that one.

More interesting, I thought, are the pieces that required the artist to use the actual process of news publishing to express their message. Emily Jacir, for her “Sexy Semite” piece, “asked Palestinians to place personal ads in The Village Voice seeing Jewish mates in order to be able to return home utilizing Israel’s Law of Return.” The piece in the gallery consists of a glass case of several issues of the Voice, with the ads circled with red marker. Another piece by Robert Gober, called simply “Newspaper,” is a pile of ten bundles of old newspapers bundled with twine, that upon close inspection turn out to have ads superimposed with the artist’s own photographs:

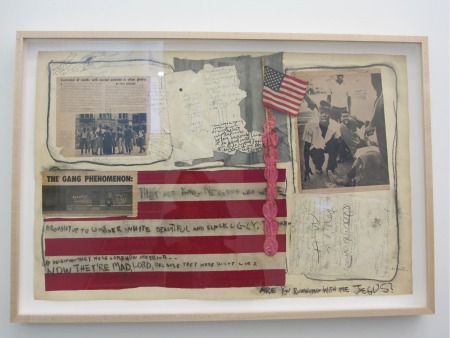

Many other artists use newsprint as filler material for collages, or as a canvas upon which to draw or paint, but I did not get the impression that these pieces were necessarily “about” the “news.” The oldest pieces in the collection, for instance, are a pair of stirring collages by Judith Bernstein, created in 1964 and 1968, in which headlines about Jim Crow and the Vietnam War were covered with pieces of American flag and the artist’s angry scrawls. (One of them, “Are You Running With Me Jesus?” pictured below.) The description of the pieces compares this process to blogging: “Much like a contemporary blogger who conjoins content from multiple sources and then reacts passionately, this work evinces a desire to claim a voice with which to speak back to the stories of the day.” That comparison, of course, is itself a superimposition of a new meaning onto the artist’s work, as the art was created decades before “bloggers” existed.

In lieu of an exhibit catalog, an editorial duo borrowed from the Latitudes project are producing a weekly tabloid newspaper about the exhibit from within the gallery itself, called “The New City Reader.” Several specialty “information-gathering” organizations—like StoryCorps, the Center for Urban Pedagogy, Columbia University’s C-Lab, etc.—have also set up shop in one of the floors of the exhibit to work there for the duration of the show. This was probably meant to give a “newsroom” feel to the gallery, highlighting the interactive nature of news and information. In actuality, though, seeing people sitting silently at desks staring at their laptop screens, looking bored, has the opposite effect.

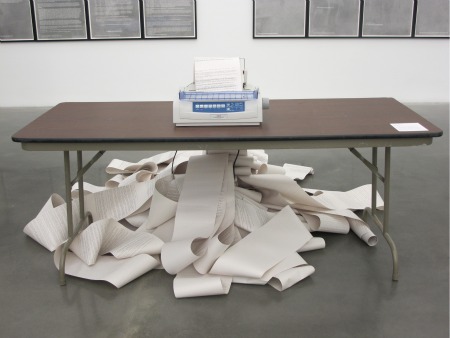

The benefit of spreading the newsprint issues around the gallery and inviting visitors to pick them up, though, is the pleasant surprise of seeing ink smudges around all the doorways and elevator buttons on the museum’s bleach-white walls. Similarly, another piece, below, splits through the gallery’s silence every few minutes with the welcome buzz of an inkjet printer. Hans Haacke’s piece pulls news stories from 30 RSS feeds and prints them out onto a long spool of paper. Its plaque declares that “The massive tangle of recent tragedies and injutices highlights the temporality of ‘the news’ in any given moment.”

In the end, “The Last Newspaper” does not necessarily tell us anything new about the business of news, nor the process of reporting or storytelling, nor does it address the changes in technology that are lately causing upheaval in the industry. I do not understand why it is called “The Last” anything, and at times it seems to have no coherent message, no urgency at all. That may just be disappointing to a museumgoer who happens to also be interested in journalism. Kyle Pope, editor of The New York Observer, wrote in his entertaining review, “the exhibit suffers from a randomness that reminded me of a bad small-town daily, a mixing of spaghetti dinners and Eagle Scout announcements I do my best to avoid,” and I am inclined to agree.

Its misleading name aside, the exhibit seems to be a celebration of the newspaper as a physical object of art, and as a means for social and political expression. The best pieces are the ones that play with the abstract concept of a daily newspaper: the absurdity of collecting a day’s events, filtering it and framing it into a compact bundle of paper, which then in turn shapes its readers’ perception of those events while supposedly providing a definitive historical record of them. Until, that is, the paper crumbles and the ink fades away.

Lauren Kirchner is a freelance writer covering digital security for CJR. Find her on Twitter at @lkirchner