Newspapers have been getting into some rather non-newspapery businesses of late: from the now-ubiquitous wine clubs to The New York Times’s film club. The Guardian even has a fashion store. Desperate times, it seems, call for gentry-baiting measures.

This Tuesday, The Washington Post added to this collection of extra-curricular revenue streams an online education venture called MasterClass. The paper is offering seven online courses written and conceived by Post editors and writers and designed by curriculum and new media experts. Prospective students can take “Building Audiences for Your Digital Content” with the Post’s head of digital news products, Katharine Zaleski, or “Spy Fact and Spy Fiction” with David Ignatius. One course that sounds particularly useful, given the rate at which the abacuses are moving in Congress, is “How the Federal Government Budgets and Operates.”

For now, the courses cost a cool $199-$299—and its creators are hoping enough readers will fork out to make the venture worthwhile.

Candy Lee, MaterClass’s chief advisor and developer, says that discussions about the classes began last year as a way of further utilizing the Post’s experienced and talented editorial team. As the paper’s VP of marketing, Lee had been holding events with Post staffers for years, but these had their limits. The events were “wonderful and popular,” says Lee, “but they require readers to come to specific location, and you need to be local. We have so many people who love our journalists and would like to hear more from them but aren’t local. Or, they are local but can’t get to a particular place at a particular time to hear them speak.”

The initial idea was to reach readers online through something simpler than fully developed curricula—something more a talking heads-type deal. But Lee, who has a Ph.D. in media and education, was attracted to the idea of designing courses that would pair Post staffers’ expertise with online interactive media, like simulation and exploding maps, which she says are “great learning tools.” A series of reader surveys suggested there was interest and revealed potentially popular subject areas. “The Wines of Bordeaux” was presumably a no-brainer.

Some readers will hear a familiar ring in the Post’s latest revenue grab. The New York Times has been involved with higher education for decades and solidified its dedication to schooling in 2003 with The New York Times Knowledge Network. Through the Network, the Times has provided newspapers and supporting curriculum guides to universities and in 2007 expanded significantly by offering the paper, webcasts, and archival material online to students in non-credit courses across the country. In January last year, the Times went further and began awarding for-credit certificates in conjunction with fully accredited colleges.

The difference between the Post’s venture and the Knowledge Network is that MasterClass’s courses were created from scratch, over nine months, by staffers and curriculum experts, rather than professors, and are in no way affiliated with universities. “The courses are meant as personal enrichment courses and an opportunity to develop your own interests further, whether you’re a novice or well known in a particular field,” says Lee. Pass an end-of-course quiz and you will get a certificate of completion, true, just don’t staple it to your Yale application.

Ignatius’s spy course, like all of the others except for Bordeaux 101, is broken up into eight sections and will take you about fifteen to twenty-five hours to complete, depending on how much of the supporting material you read. Students kick off with British moles and John le Carré and end with the world’s great spy cities. It sounds fun enough for fans of codewords and dark alleys, and Ignatius—seen in a video here explaining the course—has as formidable a résumé as you could expect for anyone teaching a spy fact-and-fiction course for a major US newspaper (a unique position, admittedly). He’s the paper’s twice-weekly columnist on international affairs and has written eight spy novels, including Body of Lies.

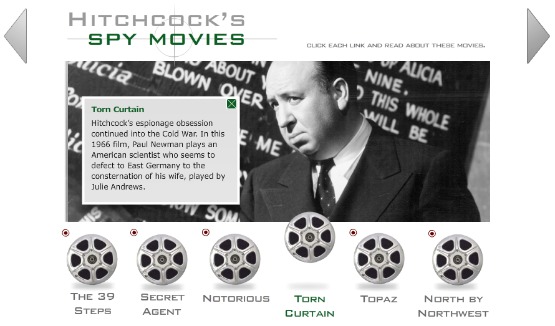

Here is an example of what the course looks like on screen:

But when I had him on the phone today I had to ask: Why the hell would he want to do this? Surely this was a time-suck and distraction from the day-to-day. Another get-out-there-and-save-the-paper deal journalists increasingly have to endure.

For one, Ignatius told me, he’s known Lee since college. But it’s more than that. “For years as a Post editor, I thought we should find better ways to make use of the things that people on our staff know,” Ignatius says. “One of the most frustrating things as an editor sometimes is to feel like you’re getting only a little bit of the creativity that’s there with the people who are partaking.”

Lee says the enthusiasm was similar among all of the newsroom staff she approached. “The newsroom understands the value of new media,” Lee says. “They’re deeply absorbed in it themselves. The idea that they could be on the ground floor of something that combines their expertise with new media was very attractive to them.”

It did prove a time-suck, though. Ignatius was initially told it would take fifty hours to write the curriculum, but the project took much longer. A frequent international flyer, he remembers typing out sections of the course in airport lounges where his “computer crashed” and was plagued by “all those nightmare things that can happen technically.”

Now that the course is together, three “learning advisors”—all trained teachers—will take over, interacting with enrollees and fielding any questions. Ignatius is relieved. Describing the advisors as MasterClass’s equivalent of teaching assistants, he says, “I am hoping that the professor, which would be me, won’t have to do much work at all, because I have lots of other things to do.”

There have been some minor concerns in past cases of newspapers venturing out in search of extra dollars. Some grumbled about potential conflicts of interest in newspaper wine and film clubs—but those clubs operate independently from their papers’ related editorial sections. And famously, at the Post itself, publisher Katharine Weymouth landed in hot water last July after it was revealed she had invited lobbyists to her home for an exclusive “salon” where, for a price of up to $250,000, guests would mingle with Congressmen, Obama Administration officials, and—most alarmingly—Washington Post staffers. The planned dinner was cancelled and the paper properly shellacked by its rivals and its own workers.

There appears to be little potential for conflicts in MasterClass, a kind of digital leisure college for the paper’s educated and established readership. But it probably wouldn’t sit well with more traditionalist pressman like, say, Len Downie. After all, in these courses, Post journalists are opening up about both themselves and their technique, extending their brand, and taking a further step away from the more dispassionate and impersonal reportage of yesteryear.

“The bundle that used to be marked ‘journalist’ is being unbundled right now,” says Ignatius, who remembers the days when he avoided the vertical pronoun. “That’s just the way it is. Every columnist is a brand name. The David Ignatius brand is associated with a certain subject and body of experience. What I’ve done [with this course] is really to open that up and share a different and deeper part of it. Once upon a time, somebody might have said that’s un-journalistic to do. But I don’t think any sensible person would say that now.”

Joel Meares is a former CJR assistant editor.