It was inevitable that the FDA’s new proposal to put graphic, and often gruesome, pictures of dead bodies and diseased lungs on cigarette labels would provide a field day for clever headline writers and pundits.

“FDA is stepping up and kicking butts,” said the Newark Star-Ledger, whose editorial board compared the proposed designs to “a fortune cookie with a death message.” Newsday opined that “for cigarettes, a picture is worth a thousand warnings,” so “bring the images on, and the starker the better. Show tracheotomy patients inhaling through the holes in their necks. Show the blackened, failing lungs. Add in pictures of children at the funerals of their tobacco-addicted parents. Perhaps showing the effects will prevent them.”

That’s certainly what government health officials and anti-smoking advocates are hoping. They were given an added boost this week from media coverage following the highly publicized announcement of the Food and Drug Administration’s new cigarette labeling campaign. The combination of disturbing pictures and new warnings provided a perfect opportunity for prominent display in print and on television (lots of local TV stations jumped on it). But the chance to showcase new website bells and whistles with slideshows and real-time online voting really lit up the online world. If you didn’t see them, you must have been camping or otherwise cutoff from civilization.

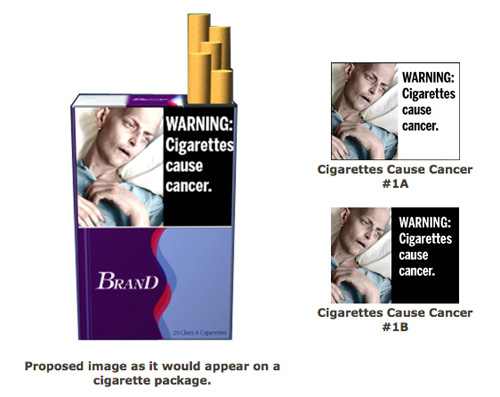

Of course the disturbing anti-smoking images—close-ups of a corpse’s tagged toe in a morgue; rotten teeth and cancerous lips; a mother exhaling smoke into her baby’s face—were as much a part of the story as the more familiar dire words: “WARNING: Smoking Can Kill You,” “Cigarettes are addictive,” or “Tobacco smoke can harm your children.”

The publicity was also fueled by a contest of sorts, with the FDA urging the public to vote on which warning labels are most likely to make smokers and non-smokers alike pause before lighting up a cigarette. The agency unveiled 36 different warning labels, available on its website, which will be winnowed down to nine finalists by June 22, 2011. In the meantime, over the next two months it will gather public comment from all sides, with a cutoff date of January 9.

Starting October 22, 2012, cigarette makers will be required to put the new warning labels on packaging and advertising in order to market their deadly products. FDA’s move to beef up warning labels is the result of a congressional mandate allowing regulation (but not banning) of tobacco products for the first time.

Studies detailing the latest health consequences of smoking, the single largest cause of preventable death and disease in the United States, often get relegated to second-class media status. It’s a kind of been-there-done-that story that is hard for health reporters to sell to editors, who always ask, “Doesn’t everyone know that smoking kills people?”

It would seem so, but the proposed new labels will be harder to ignore and much more prominent than the easily overlooked current warnings printed on the side of cigarette packs. The proposed new warning labels will be required to cover half the front and back of each pack of cigarettes and one-fifth of each large cigarette ad. Presumably, it will seem much less cool to see close-ups of the sick, dying, and dead than images of yore, such as the gorgeous Virginia Slims models used to market cigarettes to young women.

Slide shows of the proposed new warning labels images were rampant across the web. At the Huffington Post, the straightforward and dry AP story quickly came to life (or death) with a slide show of the proposed American cigarette labels, as well as others from around the world. Huffington Post’s readers were encouraged to rate them on a scale of 1 (“not scary”) to 10 (“terrifying”). It was a moving target, but when I looked, the top ranked label was a haunting image of a gaunt, bald, dying patient (average scare rating of 8.6), followed closely by the revolting mouth shot of rotten teeth and a cancerous lip (8.4), while in third place was a picture of a patient’s naked torso with large surgery staples running down the middle of his chest (7.9).

You get the idea. To some degree, it is obviously a Rorschach test, with the emotional reactions of viewers based to some degree on how squeamish they are, their experience with smoking and, of course, whether they are currently hooked on the habit.

CBS News posted a similar slideshow on its HealthWatch web page, as did The Washington Post and many other outlets.

It turns out that other countries are far ahead of the U.S. in this regard and many of their cigarette labels are even more disturbing and graphic. An excellent round-up piece by medical writer Rob Stein in The Washington Post, posted on its website Wednesday afternoon and on the paper’s front page on Thursday, noted that “at least 30 others countries already require graphic warnings, including some, like Brazil, that often go even further than the proposed U.S. messages.” Stein’s piece said that “Canada, which became the first country to require more graphic warnings in 2000, has seen a significant drop in smoking,” and that most research indicates that more graphic images can help discourage cigarette use.

“All the evidence does point to the fact that these things do help,” said David Hammond, a Canadian researcher who worked with the ad agency that helped develop the FDA. Stein quoted his estimates that about one-third of smokers say the graphic warnings reinforced their motivation to quit, and a similar number of former smokers said they were reminded of why they quit. Experts say that the warnings need to be rotated and stay fresh because they get stale.

However, Stein noted that some studies suggest that, “some strong warnings may, paradoxically, encourage smoking.” That position was echoed by historian Edward Tenner, an online correspondent for The Atlantic. “There’s evidence it may backfire,” he said, citing research linking smoking to self-esteem. “Actually Death Cigarettes were a popular novelty brand in England in the 1990s. Wouldn’t it be better to have, say, quit-smoking toll-free numbers in ultra-bold print, and other links to anti-smoking resources? We need not blows to the solar plexus, but the same sophistication and ingenuity that promoted the cigarette habit to begin with,” he wrote.

Other reactions voiced in comments on various sites ranged from the “It’s not enough” camp to the “don’t tread on me health police” variety: “How lovely. I have to see the stained consciences of the morality police externalized in technicolor when I indulge in an occasional cigarette, for pleasure and by my own free choice,” wrote Jacob of New York on The New York Times’s site. The paper splashed its story across the front page too, accompanied by the headline “U.S. Wants Smoking’s Costs to Stare You in Face.”

Finally, turning to some unscientific, man-on-the-street evidence, this correspondent encountered two Italians smoking outside a Stamford, Connecticut restaurant. Turns out they had not yet seen the American media splash over the new warnings but had seen similar warnings on cigarette packages in Europe. They dismissed them as unlikely to be effective, saying they were well aware of the hazards they faced but weren’t willing to give up the habit. Siena Restaurant owner Pasquale Conte, age 45, and a pack-a-day smoker who started in Italy at age 15, thought a far more effective approach was economic. “Raise the cigarette taxes and make them $25 a pack and you’ll have more impact,” he suggested, saying that he was not deterred by the $8.50 he now pays for a pack of Marlboros.

Cristine Russell is a CJR contributing editor and the immediate past-president of the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing and a senior fellow at Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. She is a former Shorenstein Center fellow and Washington Post reporter.