President Obama wants “to reach a level of research and development we haven’t seen since the height of the Space Race,” he said in his State of the Union address. Yet, as the twenty-first century approached, science productivity in United States actually declined, plunging 29 percent between 1990 and 2001, according to a recent National Science Foundation (NSF) working paper.

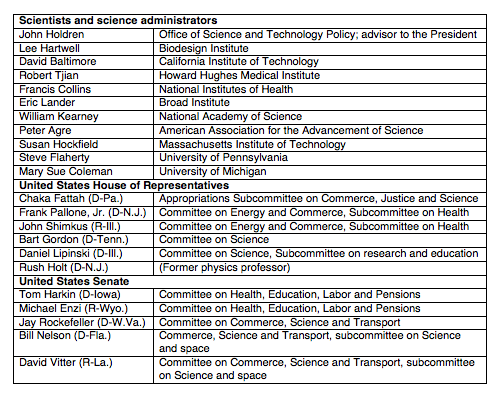

The paper measured productivity in terms of the human and financial resources needed to publish science and engineering papers. The trends, according to the NSF, “are worthy of attention because they indicate a marked shift from a historical pattern.” However, the study elicited only one article, in Scientific American. I wrote it. And no one from a who’s who of American science would comment for the story, including:

Why? Bad news jeopardizes funding. For scientists and science administrators, the preferred storyline depicts science advancing and generating breakthroughs, the master narrative informing President Obama’s speech.

The president puts biomedicine at the top of his list for additional investment. Over the last quarter century, health-related research has grown to 52 percent of U.S. government, non-defense R&D spending, with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) receiving the biggest tranche. However, according to the NSF, research productivity in medical and life sciences fell further than in any other field, by more than 30 percent between 1990 and 2001. During that period, the NIH budget nearly tripled, rising from $7.6 billion to $20.5 billion. Although we seem to be getting less for more, a spokesperson for NIH director Francis Collins declined to comment for the Scientific American piece and again for this article.

No comment came from the funders and overseers of science in Congress either. Representative Bart Gordon, who was chair of the House Committee on Science and Technology while I was reporting for Scientific American, was mum. Contacting additional members of Congress under the aegis of CJR produced the same result. The executive branch was no better. A spokesperson for Obama’s top science advisor, John Holdren, who heads the Office of Science and Technology Policy, declined requests for comment from both Scientific American and CJR.

The president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Alice Huang, did comment for CJR, although she emphasized that she was not speaking for AAAS. Huang criticized the NSF’s strategy of simply tallying the number of research papers.

“Such correlations between quantity of publications and the resources [necessary to produce them], and not in quality [of the publications], are hard to explain and may indeed not be meaningful at all,” she wrote in an e-mail, adding that several factors might account for the decline. First, “investigations are more technically complex and thus more costly.” Second, researchers are spending time “on tasks that do not result in peer-reviewed scientific publications.”

Johns Hopkins University is the number one academic recipient of federal research funding, according to the NSF. Its vice provost for research, Scott Zeeger, said the NSF study was “not a measure of productivity we as a society care about.” Zeeger added that “it takes a long time to know the significance of a paper,” and science has become more difficult and expensive because of the “maturing of the research enterprise.” Zeeger pointed to the Large Hadron Collider in physics as an example of increased maturity and expense, a dynamic he said was “also true of biomedicine.” Zeeger nonetheless maintained that recent years have been “the most exciting times for science” and that “we will see more groundbreaking discoveries in the next ten to twenty years than ever before.”

Scientists aren’t the only ones that have been reluctant to explore the twenty-first century decline in research productivity. The media, from scientific journals to popular science and general news outlets, have also been mute concerning the NSF study.

In 2007, Science reported on an earlier NSF finding that the absolute number of academic papers published by U.S. authors had plateaued—but its article missed at least one key detail. According to the NSF, the number of published papers leveled off as spending grew, an important (as far as taxpayers are concerned) observation omitted by Science. Moreover, Science did not cover the more recent NSF paper. A spokesperson for AAAS, which publishes the journal, declined comment for Scientific American, saying “it appeared to be a remix of a prior report…” The spokesperson “checked with multiple people and nobody had any other reaction or knew what to make of the findings…”

Those who believe science is advancing fastest may be least likely to recognize or acknowledge disconfirming evidence. The Singularity Hub is a blog and news network covering science and technology developments it expects to lead to the “singularity,” a moment, following exponential advances, “when we will transcend current intellectual and biological limitations and initiate an intelligence and information explosion beyond imagining.” I asked the Hub’s editor, Keith Kleiner, if there was a way to square the NSF study’s findings with exponential advance. Kleiner declined to comment.

A more widely read web publication, Xconomy, also posits a form of exponential progress, and did not cover the NSF study. Few people do their jobs better than the site’s national biotechnology editor, Luke Timmerman (recently named one of FierceBiotech’s top five writers, along with journalists from Forbes and The New York Times), and even he was not initially aware of the study. After reviewing it, however, his comments echoed those of AAAS president Alice Huang.

“I think it’s possible this could be an important and worrisome trend, but I’m not sure tallying the number of published articles is the best way to look at the question of research productivity,” he said.

Xconomy targets a readership of entrepreneurs, business and technology executives, venture capitalists, and university researchers and officials. So long as deals are happening, there seems to be little impetus to audit the value of basic research. When I asked Timmerman if faith in the exponential economy might create a coverage blind spot, he didn’t reply.

Xconomy, in addition to earning revenue from traditional online advertising, also derives income from an underwriting program which allows companies and other institutions to be listed as partners on the Xconomy site and receive other benefits such as participating in networking events. Thus Xconomy not only reports on science, technology, and industry, but facilitates interactions between them.

Similar dynamics obtain at The Economist which, with its events and intelligence arms, represents a kind of scaled-up, global version of Xconomy.

The Economist is one of the few publications that have lately explored scientific publication trends. In an article about international trends described in a recent UNESCO report, the magazine explained the age-old scientific dominance of North America, Europe, and Japan:

They spent the most, published the most and patented the most. And what they produced fed back into their industrial, military and medical complexes to push forward innovation, productivity, power, health and prosperity.

This basic model still works, the article implied, even if “the old scientific powers are starting to lose their grip.” When The Economist’s article went to press, however, the NSF study hadn’t been published. Subsequently, I asked the magazine’s health correspondent, Vijay Vaitheeswaran, about the productivity decline in the life sciences described by the NSF. He declined to comment.

The Economist’s coverage of biomedical research has been resolutely upbeat and undaunted. A dozen years ago, in a survey of the pharmaceutical industry entitled “Horn of Plenty,” it pronounced that “New genetic knowledge means more, and more effective, drugs.” However, by the end of 2000, the magazine no longer considered the genome as the holy grail of medicine, transferring its hopes to the proteome: “Know it and you will be a long way towards knowing how bodies really work.”

By 2010 the picture had only become more complicated, involving much more than genes and proteins. “Someone should have taken note” that “junk” DNA and RNA also play important roles, The Economist chided last year. Who should have taken note is not clear, but the oversight did not diminish the magazine’s optimism. Yes, “the pipelines are empty,” but not to worry. “Genomics has not yet delivered the drugs, but it will,” the article’s headline reassured readers.

Science and technology have turned in spectacular results, a performance which could reasonably be expected to continue. Questioning this assumption, however, elicits frowns or even termination from editors of science-focused media. In 1996, for example, veteran science writer John Horgan assembled his writings for Scientific American into a book titled The End of Science. It was the end of his job. Horgan says his “managers” thought his book was “bad for business” (though he has since resumed writing for the magazine.)

The nature of the NSF’s productivity report deters coverage by science journalists, according to Phil Hilts, director of the Knight Science Journalism Fellowships at MIT. The story merits coverage, he said, “but it is so unclear what might be happening [with research productivity], it dampens most reporters’ interest.”

Hilts wondered if the study simply reflected changing authorship patterns rather than pointing to something important and fundamental, echoing the views of Alice Huang and Luke Timmerman (a 2006 Knight Fellow). That view seems dismissive, however. After all, journalism is an exercise in clarifying the unclear. The president of MIT, Susan Hockfield, declined to comment.

Unfortunately, with so few scientists and science journalists willing to discuss the matter, we may never get a firm understanding of the situation. The NSF has stopped tracking the productivity metrics used in its working paper and won’t apply them to more recent or upcoming years, according to Derek Hill, senior analyst at the NSF for science and engineering indicators. I asked Rolf Lehming, program director for the NSF’s annual report, Science & Engineering Indicators, whether publication productivity measurements would be added to the dashboard of indicators. He declined to comment on the NSF study.

As President Obama mashes down the R&D accelerator, any problems with the engine will go undetected if scientists and journalists are not willing to look under the hood. That science has gotten more expensive, and thus less productive, seems to be undisputed. If Johns Hopkins’s Zeeger is right that the rising costs come from the maturation of the scientific enterprise, research will not only fail to move forward exponentially, the coefficient of progress will actually fall. If that is the case, scientists and science reporters must seriously reconsider the master narrative of rapid, ineluctable advancement. These giant questions are worthy of coverage—and comment.

Clarification: The text of this article has been changed to reflect that Horgan said his “managers” at Scientific American, not his editors, felt his book would be “bad for business.” After the article was published, Horgan specified that he was referring to publishing and advertising staff.

Robert Fortner is a contributor to CJR.