Executive Summary

This research report examines perceptions of—and approaches to—personalization among news organizations and technology companies in China and aims to identify the current state of personalized recommendation technology within the Chinese digital news landscape. Between September 2019 and August 2020, we conducted interviews with 26 individuals from 19 organizations, pausing to adjust for the COVID-19 outbreak, and re-interviewing people we spoke with before the pandemic occurred.

We found that our interviewees considered personalization a defining element of the Chinese online news ecosystem. Personalization was a core factor for revenue generation, or, for state-sponsored media organizations, it was key for boosting relevance and attention.

In addition, regulatory bodies withhold interviewing rights for internet companies and limit their ability to create original content. As a result, platforms rely on publishers to produce content of political and social importance, while publishers turn to platforms for their popularity and distribution channels, leading to dynamic and multifaceted forms of cooperation and competition between the two. Subsequently, what we found was the occurrence of blurred boundaries between media organizations and technology companies, leading to the loss of news branding and a struggle to redefine the concepts of information, news, and entertainment.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw implemented personalization largely decrease; however, as our interviewees emerged from lockdowns and resumed operations, all agreed personalized distribution of information would continue to ramp up.

As Chinese-based media technologies become a larger disrupting influence globally, the findings of this study should provide insight into—and comparison with—a news landscape that is increasingly algorithmically curated yet politically restrictive and dominated by news apps that market their personalization AI technology as their core product, instead of only relying heavily on it. The report also explores the Chinese news environment before and after COVID-19.

Key findings

- Platforms and publishers’ definitions of personalization have been directly affected by ByteDance’s news aggregator Jinri Toutiao’s popularization of personalized recommendation technology. The term “Toutiaoization” has been adopted to describe the widespread use of implicit personalization when targeting content for individual users.

- Personalized recommendations are now considered a core aspect of media technologies, with all organizations among those interviewed pursuing it to varying degrees, from experimenting with personalized feeds on their apps to managing accounts on personalized news aggregators. The extent to which these organizations use personalization is generally influenced by their positioning, priorities, and technical capabilities.

- Our interviewees considered traffic, engagement, and advertising revenue key reasons to pursue personalization, outweighing numerous worries about the negative effects of algorithmically driven, personalized content. These concerns ranged from echo chambers to misinformation; however, proponents of personalized algorithms argued that they are great equalizers between media organizations and platforms and are able to satisfy the needs of users.

- Despite the structure of China’s news ecosystem, which divides commercial media from state-sponsored ones, noncommercial institutions feel the same drive to ramp up personalization for attention and relevance, if not for revenue.

- While engagement and traffic were priority concerns for our interviewees, we found commercial and noncommercial publishers turned to personalization because of a general desire to increase news distribution. Platforms, on the other hand, did so to augment their stickiness, meaning their product’s ability to engage users, and profit generation.

- Platforms rely on publishers for content, while publishers use platforms to increase distribution rates and attention, a dynamic that has resulted partly from China’s media regulations and partly from the popularity of technology platforms. This has resulted in closer cooperation between platforms and publishers.

- Some interviewees viewed such cooperation positively, while others cited problems including blurred boundaries, a loss of news branding, and changing definitions of media as a result of the clamor for attention and engagement and a shift from providing information to offering entertainment. The collaboration and competition affects how media companies work and the content they produce, which is further complicated by publicity and propaganda requirements.

- In China, media organizations operate under a shifting yet ubiquitous regulatory framework, but the majority of our interviewees did not feel it adequate enough to fix quandaries such as filter bubbles or rein in the prevalence of algorithms in their work.

- Our interviewees did not expect Toutiao to take responsibility for the health of journalism. Instead, they saw current problems as built upon long-standing issues that accompanied the rise of the commercial web.

- At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, implemented personalization largely decreased as media companies pivoted to pushing information about the novel coronavirus. However, all of our participants agreed personalization is an irreversible, growing trend.

Introduction

The flood of technology companies into the news ecosystem, and their emphasis on attention and advertising, has driven news institutions to restructure and refocus their processes and approaches. Previous Tow Center research has noted how “technology platforms have become publishers in a short space of time, leaving news organizations confused about their own future,” highlighting the disruptive influence the digitization of media has caused as it breaks down material and cultural barriers to mass publishing.1 In the West, technology platforms like Facebook or Twitter have become key players in the news environment, often in spite of intention or desire. Moreover, any level of concern these businesses have for the health of journalism is overshadowed by their commercial pursuits and goal to increase user counts on their platforms.2

One of the most visible changes accompanying the switch to digital, and the dominance of technology companies, is the prevalence of algorithms that “influence, to some extent, nearly every aspect of journalism, from the initial stages of news production to the latter stages of news consumption.”3 Since the 2002 introduction of Google News, automating and semi-automating functions formerly overseen by human editors have steadily increased. Today’s media technologies are often defined by algorithms, which are also assuming a greater place in newsrooms as well as becoming more responsible for selecting the news people see online.4

This has swung a newsworthiness metric toward personalization, defined here as “a form of user-to-system interactivity that uses a set of technological features to adapt the content, delivery, and arrangement of a communication to individual users’ explicitly registered and/or implicitly determined preferences.”5 In the Western world, news aggregators, search engines, and social media platforms increasingly offer personalized content through machine-learning models, but news publishers too, hoping to expand their stickiness, have progressively adopted personalization strategies both explicit, using direct user inputs, and implicit, inferring preferences from collected data.2 Aside from this distinction of self-selected recommendations with user-fed criteria, and pre-selected recommendations determined by the media organization, news recommender algorithms also make suggestions on the basis of metadata and content, collaborative filtering (based on user and community data), data on their users, or a combination of the three.6

The algorithmic culture built up from the proliferation of machines and Big Data, which are driven by human thought and conduct, has led to uncertainty and concerns. Publishers must decide how best to navigate their relationships with technology companies while algorithmic opacity complicates decision-making processes. The pursuit of attention and audience, manifested through an emphasis on personalization by news organizations, raises questions about bias, invisible gatekeeping mechanisms, and protection of consumer data.

While personalized algorithms potentially filter out a diverse range of content in favor of user-directed interests, these filtering decisions can also mean downplaying or overemphasizing certain information, especially in the politically surveilled Chinese cybersphere, where algorithms continuously scan and censor material they deem unacceptable.7

As news organizations compete with platforms for attention, relevance, and revenues, their approach to personalization is directly affected and defined by the competition with technology companies; a clear phenomenon within the Chinese digital landscape.

Of China’s 904 million internet users, 99.3 percent go online via their mobile devices, spending significantly more time and money on apps compared to their American counterparts.8 For reasons including the proliferation of smart devices and the digitization of the retail industry, research suggests the time a Chinese mobile user spends online may be twice the amount of the average US adult’s, the length of which has only increased during the pandemic.9 As of March 2020, almost all of China’s 731 million online news consumers read, watched, or accessed news sources through their mobile devices, where the news ecosystem is largely made up of publisher apps, news aggregators or distributors, and social media platforms.8

News aggregators and their predecessors, news portals, are a leading source of news in China, and have been around since the early development of the commercial web. In the mid-1990s, the internet introduced web-based news portals, which later developed into news apps as smart technology proliferated. In subsequent years, traditional party media retained their political prominence and state-backed funding, but the news industry has diversified, with new competitors and information distribution avenues like mobile apps or independently operated social media accounts. Technology platforms began to compete with state and traditional publishers for attention and revenue. A distinct shift occurred after news aggregator Jinri Toutiao, the flagship product of Beijing ByteDance Technology, was launched in 2012 to provide a “unique, personalized and comprehensive content experience” powered by “machine and deep learning algorithms.”10 Unlike technology companies such as Facebook or Google that heavily rely on recommendation algorithms, Toutiao sells an AI-centric approach, positioning personalization as its core service when distributing information to users. As ByteDance CEO Zhang Yiming spelled out in 2015, Toutiao is, “technically speaking, the mobile internet plus a personalized recommendation engine.”11 The mobile news app aggregates and recommends content to users. Publishers can also open and manage accounts on the platform, which they frequently do, along with maintaining accounts on various other social media and news apps. Larger publishers also run their own news apps.

ByteDance is currently the world’s most valuable unicorn startup with personalization driving all of its subsequent products, including the best-known, TikTok (douyin), a social media service for sharing short-form videos.12 However, while TikTok falls comfortably into the categories of social media and entertainment, Toutiao’s origin as a news provider has altered the entire Chinese news industry and pushed it toward the adoption of personalized recommender technology.

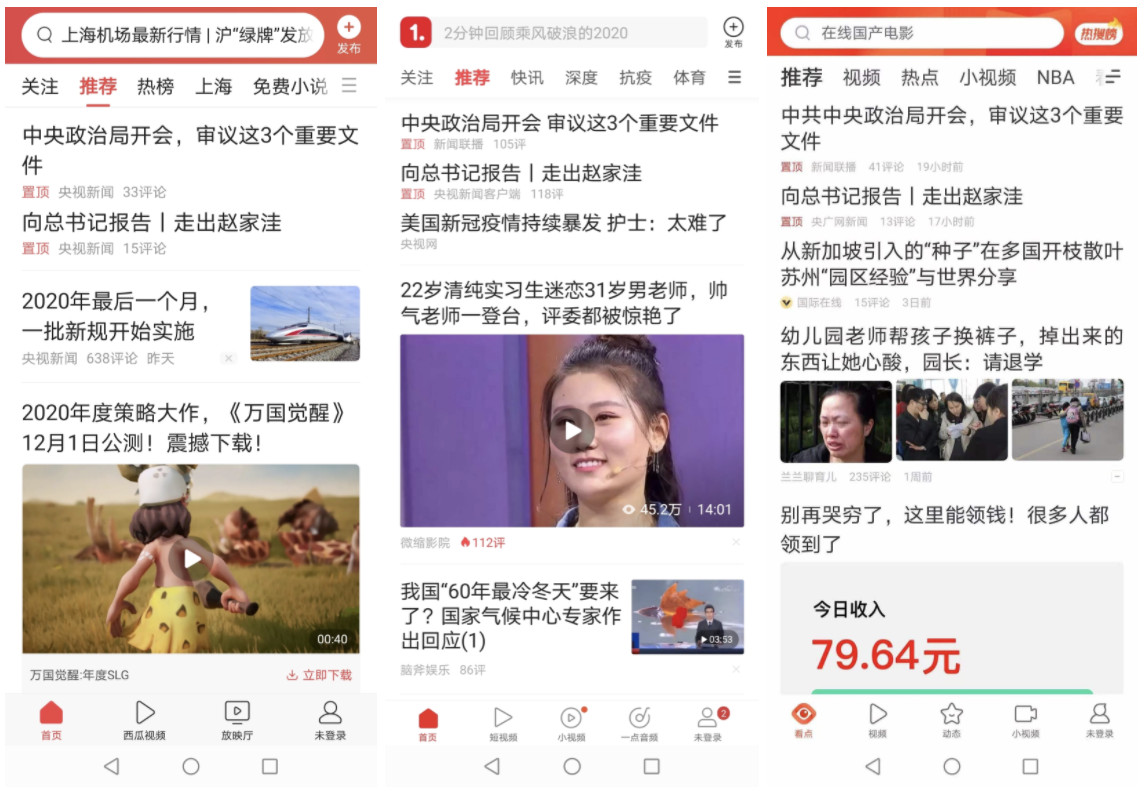

Within the Chinese media studies and industry, the term “Toutiaoization” (“头条化 toutiao hua”) has emerged to refer to the widespread use of algorithm recommendation technology by information distribution platforms to provide users with personalized and targeted content on a curation level, as opposed to on the article level.13 In other words, the newsfeed offered to the user was itself being personalized, not the contents within a news article. The model of personalization as the product began with Toutiao and has since been similarly applied to other news platforms, including Kuaibao and Yidian Zixun (Figure 1). These personalized news aggregators (PNA) prioritize the personalized distribution of information and content beyond the latest news headlines, often bordering on entertainment.

Figure 1: Home interfaces for three personalized news aggregators. (From left to right: Toutiao, Yidian Zixun, and Kuaibao.)

The drive for personalization in news aggregators is galvanized by a pursuit of traffic and advertising and enabled by vast amounts of data.14 This, combined with the underdeveloped legacy market, a fast rate of turnover that forces companies to “compete on the edge,” and a government-backed push for algorithm and AI development has led to deep changes within the news ecosystem.15,16 Just like their Western counterparts, Chinese publishers are adapting to the rise of platforms that are restructuring the media environment, including the diversification of avenues and channels through which content can reach an individual, leading to a potential loss of branding, user data, and revenue.

However, top-down, ever-present regulation in China means that publishers and platforms coexist under a set of governing rubrics that are very different from those in the West. Examples of government oversight include directives from the Cyberspace Administration of China, restrictions on visas and press credentials for journalists, and delineation of which media organizations are certified to report on issues of social and political importance. These boundaries and forms of media control are continually shifting, requiring Chinese media and technology companies to adapt to dynamic sets of hidden and overt provisions and obstacles, which often translate into a heavy amount of self-enforced regulation and censorship. Mass data collection has provided the Chinese technology industry with an edge, outstripping the amount the United States or Europe can collect. In 2020, however, China proposed a draft Data Security Law that begins to set out how consumer data are accessed, handled, and gathered.17 Anti-Monopoly Guidelines and the Personal Information Protection Law in draft forms followed in subsequent months, introducing restrictions designed to rein in internet and technology companies; in the months leading up to 2021, large technology companies including Tencent and Alibaba have been the recipients of fines, investigations, and increased scrutiny.18–20 The consequences of these developments remain to be seen, but offer a clear example of the prevalent and shifting forms of supervision under which our interviewees work.

We describe how publishers and platforms view and approach personalized distribution of news and examine how they operate within an increasingly algorithmically curated yet politically restrictive environment. We compare their responses from before and after the outbreak of the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, as the pandemic introduced new business realities.

Methodology

This project on news personalization in China began in July 2017 at the Columbia Journalism School and was conceptualized at the Digital Media and Press Freedom in the Era of Big Tech—A Case Study on China conference, hosted by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism and the Brown Institute for Media Innovation. The one-day conference discussed the difficulties of delving into digital media research, the information ecosystem, and the role of platforms and publishers within China.

The main research questions that underpinned our work included examining the perceptions of personalization among news organizations, so we asked how personalization affected decision-making processes. How do publishers perceive the role of personalization at their media outlets? How important has it been for the growth of their companies? What attitudes do they hold toward personalization? How do they see the future of personalization in news in China?

Another line of inquiry focused on the practices and policies of personalization within Chinese news organizations. How does personalization affect journalistic practices? How much does competition with other organizations factor into it? What level of human intervention do they have?

We also asked our interviewees about the current state of the Chinese news market, and how certain characteristics or restrictions shape the work they do.

Lastly, as a result of COVID-19 occurring in the middle of our project, a component of our research concentrated on alterations to work practices and attitudes before and after the outbreak.

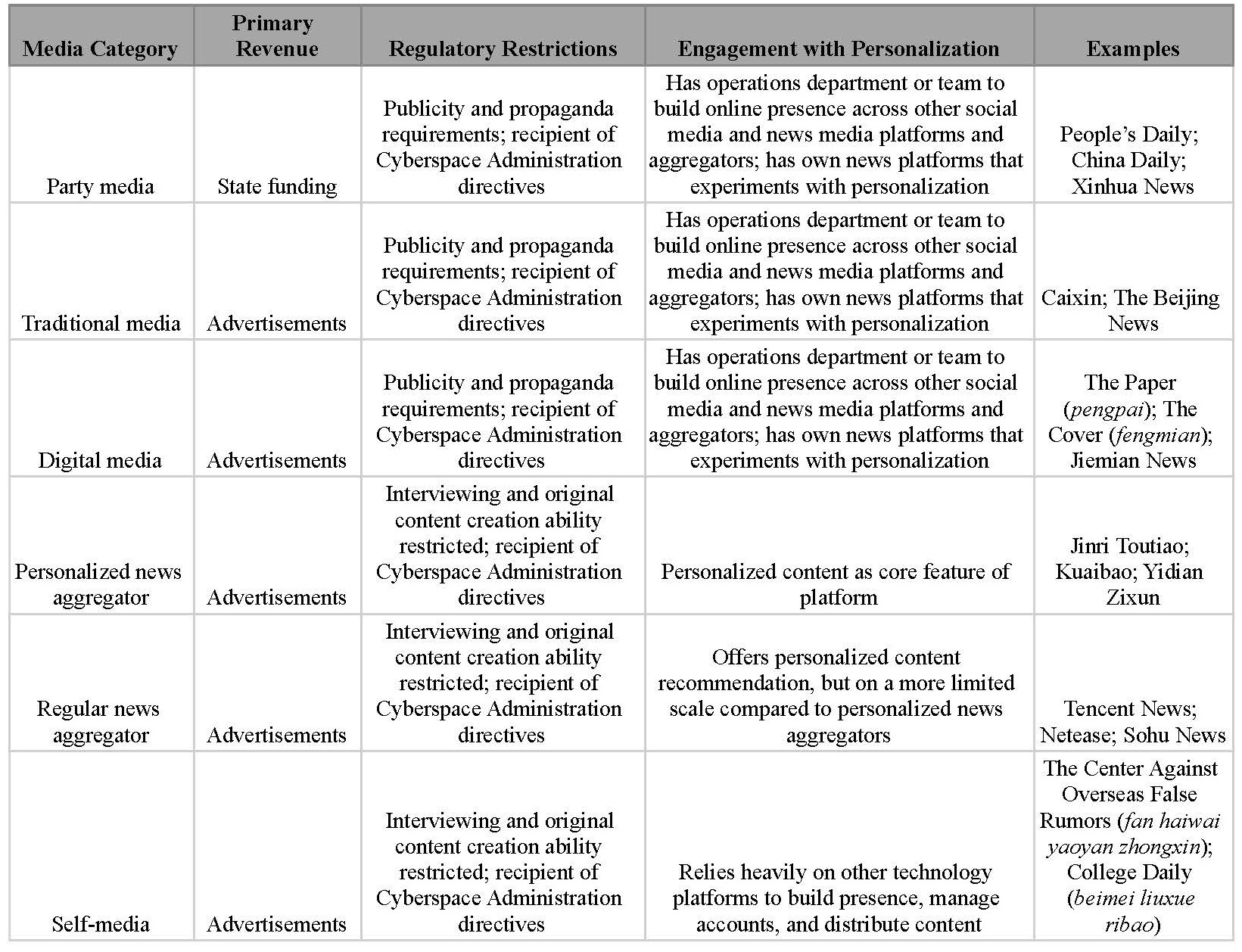

For the purpose of our research, we created a list of Chinese media outlets including regular news aggregators (RNA), personalized news aggregators (PNA), party media, traditional media outlets, digital media outlets, and self-medias: a term popularized in China after the mid-2010s that refers to independently operated accounts run by individual users who produce news content on larger social media platforms21 (Table 1). News aggregators were divided into those defined by personalization and those that were not. Personalized news aggregators market their personalization as the core feature of their product, while regular news aggregators have a personalized component but did not build their platforms around it. Traditional and digital media outlets were separated by their origin point. In other words, while all traditional media outlets curated a presence on various platforms, we set apart those that began online. We also separated traditional media and party media into two categories, with the latter as news organizations that were state-sponsored even though both types originated from offline publications. They produce news and compete with news outlets for attention. This categorization considers both an outlet’s emphasis on personalization and its relationship to social media. We added to the list professionals and experts on news personalization in China, representing academia as well as the industry.

We started to schedule interviews in September 2019, introducing ourselves as researchers from Columbia University working on a Tow Center for Digital Journalism project. The COVID-19 outbreak in China in December 2019 derailed and delayed our project by approximately five months, during which time our three researchers were also under various stages of quarantine multiple times in China and news organizations were unable to schedule interviews. As a result of the pandemic, we re-interviewed all previous interviewees to ask them if their attitudes toward or policies of personalization had altered as information channels and content focused on coronavirus news. Those we interviewed after the outbreak began were specifically questioned whether their responses would have differed before and after COVID-19.

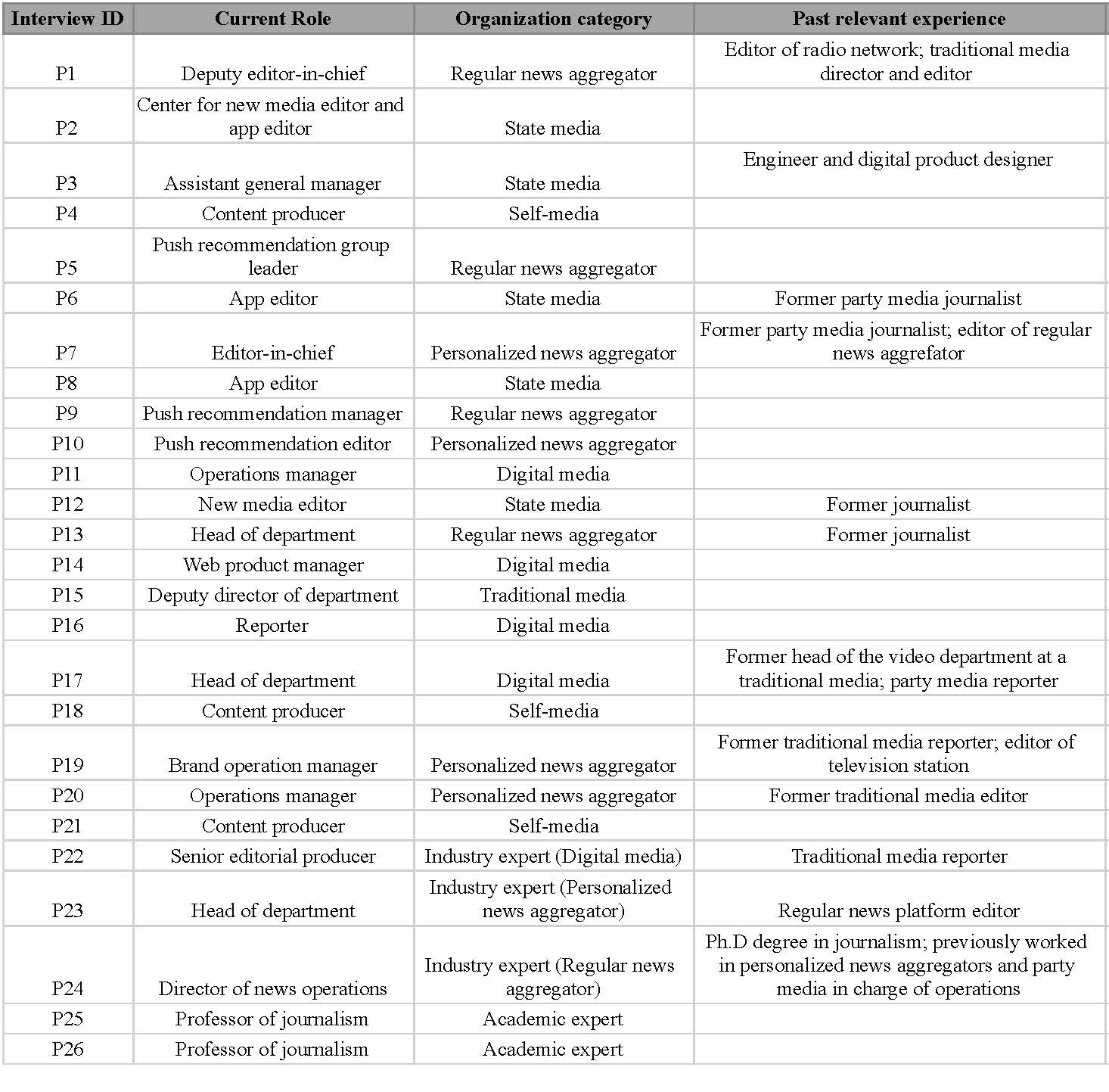

In total, we conducted interviews with 26 individuals from 19 organizations, including professionals with academic or industry expertise. In all cases, we aimed to find interviewees in high editorial or managerial positions. Interviews were conducted and transcribed in Mandarin Chinese, in which all researchers are fluent, before being translated into English by the authors for this report. In cases where interviewees used English terms in their responses, the words have been italicized.

We promised the participants anonymity in regards to the use of their names and their organizations. Instead, we labeled them from P1 to P26 for quote attribution throughout the report and provided contextual information for each interviewee (Table 2). Since ByteDance’s Jinri Toutiao is a key player, we mentioned the organization by name when other media outlets referred to it; however, we have not distinguished interviewees who work for Jinri Toutiao. Identifying data have been kept confidential and are not discernible from the report.

Interviews conducted before January 2019 were completed in person in Beijing or Shanghai. After the outbreak began, the rest of the interviews and re-interviews were held largely by video or phone with only some exceptions. These were semi-structured interviews that lasted one to two hours. With the consent of all participants, the interviews were recorded, transcribed, and encrypted on our personal computers. Using the qualitative program Dedoose, we analyzed our corpus of interviews; specifically, all researchers read the transcripts and identified several themes. We coded the interviews in three waves to identify patterns and solidify concepts. Our researchers met periodically for peer debriefing and reached a consensus on subthemes to generate the following report.

Perceptions of Personalization

From our conversations with professionals, what emerged was clear acceptance of personalization as a core feature of the Chinese platform industry, along with recognition of and reflection on the problems associated with that reality. While there are some layers of explicit personalization, including the ability for users to customize interests categories, the news organizations we talked to intrinsically understood personalization as implicit, governed by sophisticated algorithms. We heard variations of this answer from all our interviewees, including those from state-sponsored, traditional media. As P6, a state media app editor, said, “Although personalization doesn’t equate to algorithms, in order to achieve it one must use algorithms. There are other functions for algorithms; however, in order to achieve personalization, you cannot move away from algorithms.” Likewise, P2, a state media app editor, said, “In fact, everyone now binds personalization with algorithms.”

“Basically, everyone is doing it.”

Interviewees across all our media categories considered personalization a central feature of the current digital news landscape, especially for platforms that viewed personalization as the foundation of their products. Several stressed that the defining business feature of their platform was its personalized algorithm, and that those who worked on the technology represented the true core of their company.

The general perception from our interviewees was that all professions in all industries were getting into personalization as a means of refining their content. Several times this was reasoned as a response to the proliferation of information, now that anyone can become a content creator. P10, a personalized news aggregator’s push recommendation editor, said, “It might be an irreversible trend because no matter if it’s a news app, or e-commerce like Taobao or short videos, all are doing personalized recommendations. If you don’t do this, it’ll seem like you’re still stuck in the era of web portals.”

Even state media viewed personalization as a core element. Reasons given for this included that it directly determines the content consumers receive, and is thus important for the product because personalized algorithms create user portraits that better match information with audience. P3, a state media assistant general manager, said, “Media organizations will definitely personalize. If they don’t do it, or they think it’s not important, it will definitely be because the cost of doing it is too high or they don’t need to do it. But if they need more users or more people for sustained engagement, and not just users opening their app only once a day, they will definitely need varied content and personalized recommendations.”

Interviewees from state-sponsored media also emphasized the relevance of personalization because users’ attention resources are limited. Moreover, while state-backed organizations can sustain themselves with government funding, they look to commercial pursuits to bolster their presence and freedom (including cooperating with brands to produce advertisements), thus rendering them unable to entirely discount the competition coming from platforms.

“Traditional media looks down on Toutiao, but they don’t dare ignore communication platforms,” said P17, a digital media publisher, citing Caixin Global, which has a presence on Toutiao and other distribution platforms to gain readers “outside their elite group.”

Although the general understanding was that all media institutions from the state-backed People’s Daily to digital media outlet Jiemian are engaging in personalization, several people told the researchers this did not necessarily mean it was being done well. Often, respondents said all companies were chasing Toutiao’s success to various degrees, but none have been able to emulate the platform’s level of stickiness and popularity.

The importance of engagement and traffic galvanized the push toward personalization. A common sentiment was that the more personalized a recommendation, the better its effect in terms of user activity and attention. Several news organizations said their internal data showed that personalized recommendations garnered better results than nonpersonalized ones in terms of click-through rate, engagement, or daily active user count. Personalization brought in the highest traffic on a publisher’s own apps and on third-party platforms; all news organizations told us the difference and impact were very clear. P13, a regular news aggregator employee, said, “Every news app is doing it. None can fight against it, because no matter what, you have to be user-oriented; otherwise your click-through rate is not good, your reposted comments are not good, and you will be criticized [by the bosses]. Even if you are not criticized, you are not comfortable.”

Many of our interviewees viewed personalization, specifically personalized push recommendations, as the best way to approach readers because of its speed, wide access, and user-interest targeting. P9, a regular news aggregator’s push recommendation manager, pointed to personalized algorithms’ ability to satisfy users’ desire to kill time. Personalized recommendations in an app, combined with an endless scroll, means users will continue to stay engaged, which generates traffic that the platform can then use to sell ads. “The business model has been proven to work,” said P9. “Maybe the value we’re creating for the user isn’t the highest, but the business model is definitely correct.” Moreover, P6, a state media app editor, noted a user may feel an emotional attachment to the news product because the user feels the “product understands him,” causing the user to engage and click more.

“This is a very bad influence on news.”

However, participants listed a litany of problems they saw as by-products, including the prevalence of vulgar (“低俗 disu”) content, which is often perceived as sensationalized information or gossip often sexual or violent in nature; echo chambers, fragmentation, misinformation, and privacy issues; and a changing perception of what news was.

From our conversations, there was an obvious concern with perceived high and low standards of news, with employees of traditional and digital media outlets more inclined to view themselves as producing serious, high-culture news, and to disparage the content they judged was prioritized by platforms. Interviewees from platforms, on the other hand, had a tendency to reject the label of low or vulgar news, a terminology the country’s internet watchdog has similarly employed to describe these platforms.22

When it came to personalization and personalized algorithms specifically, our interviewees were more aligned in their opinions. As expected, traditional and even digital media employees not only thought personalized algorithms would make consumers more likely to turn to perceived lowbrow content, but several also singled out Toutiao as the platform where such occurrences were prominent. “If you don’t exercise restraint with human intervention,” P6, a state media app editor, said, “the user may receive an unending stream of this type of information.”

The perception that personalized algorithms prioritize clickbait and vulgar content is similarly expressed by several regular and personalized news aggregators. P5, a push recommendation group leader at a regular news aggregator, related how their technologists and editors all “found that entertainment and vulgar social types have crushed all other news, which has caused many users to continuously scroll or receive or see this type of content” since the early phases of personalization. P5 shared with us their team’s experience and disappointment when they first discovered their algorithm pushed “all vulgar content; there wasn’t a single serious piece of news.”

One PNA made explicit the difference between the algorithm and the work of humans. P10 said, “On the human side, there is not much pursuit of traffic or catering to the audience with 95 percent normal news, but the algorithm recommendation side will go for more eye-catching content and prioritize traffic.” Although employees at personalized news aggregators were far less critical of the practice, P10 acknowledged that “it may be possible to attract users to click on content that verges on pornography and vulgarity.”

Several participants understood this phenomenon as a clear drawback of personalization and underscored the negative influences it had on the news industry. “But is there a way to change it?” P5 said. “It is a trend, and you can’t push it away because this trend brings us traffic, and then there is the boss’s approval, and the completion of all aspects of work, but in fact it has a very bad impact on the entire industry.”

One impact many saw being compounded by personalization was the practice of manuscript washing or article spinning (“洗稿 xigao”), a popular term inspired by money laundering (“洗钱 xiqian”). The phrase arose within the news industry to describe media (especially online media) using a variety of methods to repackage, alter, and repost original content and news.23 Given China’s weak copyright laws, protecting original content is a challenge that extends much further than the news industry, but within it, several interviewees saw self-media as the perpetrators and algorithmically driven platforms as the culprits for magnifying the problem. “Self-media lacks supervision, and it can obtain higher traffic on platforms than original authors through manuscript washing,” said P17. “In order to expand traffic, and partly to restrict the influence of traditional media, the platforms acquiesced to the existence of the practice.” As a result, publishers saw misinformation as being tied to the platformization of news, citing as an example the proliferation of conspiracy theories.

The tendency for algorithms to promote eye-catching content could thus inadvertently encourage manuscript washing. The traffic generated by secondhand articles, often due to their attention-grabbing titles and lack of paywalls, “may be judged by the algorithm to be a good thing,” P19, a personalization news aggregator’s brand operations manager, said. “This is also the reason why I think, especially at the beginning, people will think [our platform] is a manuscript washing platform, because many of our hottest articles were washed out just like this.” This only compounded the image of platforms as the home of low-cultured content.

The self-media publishers we interviewed talked freely about the practice. “Manuscript washing is a by-product of algorithm news distribution,” said P4, a self-media content producer. “We also wash what we’ve written before and what others have written. As long as the recommendation requirements of the algorithm are met, the reading volume of secondhand articles can exceed the volume of the original ones.” Another agreed that manuscript washing was an industry-wide issue and practice, but lay the blame at the feet of media control. “This problem is not only related to ineffective copyright protection but also the result of regulation,” P4 continued. “Self-media don’t have the right to interview, so if our original content has negative leanings, it can easily get banned. The result is that you either write soft articles based on firsthand information or become a secondhand information dealer.”

In the West, algorithms have been accused of downranking informative news on important social topics that are necessary for a democracy, and instead emphasizing clickbait and sensationalized information.24 Chinese scholars argue this is a quandary for China as well. “Users usually choose topics they are interested in for reading, so they often ignore some public topics,” Peng Lan, a journalism professor at Renmin University, writes. “In addition to meeting the individual needs of users, users should be guided to pay attention to public affairs, stimulate their interest in public affairs, and help them understand the wider world.”25 Others, however, have placed the onus on the values of the people behind recommendation technologies. “Algorithmic news recommendations in themselves are neither good nor bad for democracy,” writes Natali Helberger, a professor of information law at the University of Amsterdam. “It is the way the media use the technology that creates threats, or opportunities.”26

“If you only read Toutiao then your thinking will become very narrow, and you’ll increasingly become only concerned with specific things.”

Our interviewees also frequently mentioned other perceived problems. Firstly, platforms and publishers worried about whether personalized news recommendations could lead to the formation of information cocoons or echo chambers. Our interviewees often conveyed their fear that the biggest crisis of personalization is giving users what they would like to watch and thus narrowing people’s horizons. While none cited studies or concrete data to elaborate on their worries, it was a pressing concern for many. “The user only pays attention to what he wants to pay attention to,” said P13, a regular news aggregator employee. “He should pay attention to some other things too. If information isn’t spreading to you anymore, your vision will become smaller and smaller, and this is a problem.”

Intricately linked is the long-standing concern of fragmentation brought about by the rise of the commercial web. Publishers, especially, were worried this would mean important information the users should receive would not get to them. These apprehensions were frequently raised despite the daily standard content each news organization must promote. These are articles designated as of political importance, which are pinned (“置顶 zhiding”) at the top of all news apps and news websites whether they are run by publishers or platforms (Figure 2). Our participants did not believe the existence of the standard news (“固定新闻 guding xinwen”) was enough to counter the negative effects of personalization, especially when there is a clear propaganda element to the fixed news.

Figure 2: The home interface of the People’s Daily news app. News articles of political importance are designated with a red “Pinned.”

Studies examining the siloing of information as a result of personalization continue to debate the magnitude of their effect on changing patterns of news exposure and consumption. On the one hand, much has been written to warn against fragmented or “balkanized” media environments, with scholars finding that platforms’ ability to tailor user information experiences has led to information narrowing.27 On the other hand, several academic studies have found the existence of filter bubbles and audience segmentation to be relatively modest, while others point to polarization that stems from news outlets’ decisions and users’ self-selection.28 Others find online audiences to be no more fragmented than offline ones.29

Advocators of personalization argue that it serves users by mitigating information overload in the face of information abundance, an argument we heard in our conversations as well.30 According to our interviews, both publishers and platforms view information abundance as a reason for personalization because within the current attention economy, there is too little time and too much content for users to focus on. Others have found, however, that the degree of user satisfaction with recommended news was relatively separate from perceptions of information overload, and users often remain unaware of information narrowing and filtering in their newsfeeds.27 Toutiao and TikTok are sensitive to the debate and have said they attempt to increase the diversity of their recommendations by pushing other trending stories into users’ For You feeds.31 Toutiao has been named by state media and government bodies and criticized for similar worries concerning its AI-driven news, leading to Toutiao’s promises to adhere to core socialist values, the fight against misinformation, and the development of its content detection tool in 2018, the Spirit Dog Anti-Vulgar Assistant.32 Among our interviewees, these concerns existed before the novel coronavirus outbreak and were more frequently voiced when we interviewed them after the pandemic.

Several also blamed personalization for instances of toxic behavior online. P13, a regular news aggregator employee, said, “Many of these types of cyber violence have a lot to do with personalization. Some circles will be formed. Many people in the circle are fearless, feeling like they can do anything in the circle and scold others. … It amplifies the evils in people’s hearts.”

Other interviewees raised the issue of privacy and giving information to these apps. “When you offer a user personalized content, you’re actually making the user give up their privacy to you,” said P6, an editor for a state media app. However, as more than one person acknowledged, while it was a personal concern, it must be pushed aside in the face of the traffic personalization can bring: “For many journalists and practitioners in the news field, personalization is too attractive a means for bringing in users.”

Some pointed to other Chinese non-news apps, and the notoriously high number of permissions their users must agree to, and stated that, in comparison, personalized news platforms required hardly any more data. P1, a deputy editor-in-chief at a regular news aggregator, echoed a controversial opinion made by Baidu CEO Robin Li two years ago that landed Li in trouble with Chinese netizens and said, “Chinese users are more generous than overseas users. Chinese users are less sensitive about privacy.”33 P1 attributed the phenomenon to the plethora of permission-seeking apps and the makeup of Chinese internet users, where fewer than 20 percent hold a university-degree education or higher, which we explore further in the next section of the report. Others we interviewed agreed to an extent that users with higher education levels were more likely to have privacy issues. They also worried that strongly personalized content could alienate more highly educated users, due to data-collecting concerns and a perception of low-cultured content, further entrenching the divide between perceived lowbrow and highbrow audiences.

“Is it worth doing in-depth reporting anymore? I tell you honestly, I do not know.”

The concerns we’ve laid out above have left many of our interviewees worried and confused over changing definitions of news and media while information distribution streams diversified and publishers competed for attention with technology companies that often held very different priorities. Publishers such as P16, a digital media reporter, variously discussed the “vague concept of news and the lack of a true sense of news” in their own work, especially as they ventured beyond newsmaking, whether in pursuit of traffic or for party propaganda purposes, including establishing museums. As P24, a director of news operations, said, “Look at People’s Daily: They make their own songs [and] concerts, and engage in other cross-media behaviors. No matter the media, there’s no need for them to be bound by traditional media concepts anymore.”

Others spoke of how the news stories they produced often competed for space online with cooking videos and makeup tutorials, all fed through the same algorithms. P11, a digital media operations manager, said personalization made it harder to conduct in-depth investigations and reporting, and posited that “Maybe as long as it provides an increment of information, it’s all news for users.”

The apprehension then was that news is devolving into entertainment, which was sometimes attributed to Toutiaoization. “My personal feeling is that what we are currently doing is to satisfy users’ demand for killing time,” P9, a regular news aggregator’s push recommendation manager, said. “Few people seem to be really trying to gain something like knowledge, new knowledge like understanding about the society, etc.”

Several others shared this gripe, boiling down the characteristics of news consumption in the age of algorithms to fragmentation, entertainment, and multimedia and conveying their helplessness against the challenge of such changes. Some spoke of seeking a balance between pursuing traffic and their own principles, while others pointed out the irreversible transformation that has swept up all organizations and self-media. Publishers griped about the devolution of news into a game of numbers, clickability, and eyeballs, forcing them to focus on packaging news stories that would be more appealing not only to consumers but also to the algorithms. P15, a traditional media publisher, reflected how in years past, “Making news I wanted to was like being in an ivory tower. I made [news articles] regardless of the reader’s reaction, I just did it. … Now we are basically following the trends.”

“In front of algorithms, everyone is equal, and we can compete with traditional media.”

Not all those we interviewed expressed solely negative opinions about personalization. Those who work for platforms, especially, emphasized its ability to break what they perceived as traditional media’s superiority, elitism, and monopoly. “Traditional media means, ‘This is what I want to show you,’” P13, a regular news aggregator employee, said. “The entire selection and dissemination criteria are in the hands of a small number of media elites, but in the time of social media, because there is too much information, with personalization you can see what you usually can’t see in traditional media.”

From this perspective, news aggregators were considered a great equalizer, with Toutiao seen as the best distribution platform. P4, a self-media content producer, said, “Toutiao chooses cooperation methods based solely on traffic. As long as the algorithm predicts that your article has a high reading volume, you can get 100,000 or even a million [news recommendation] pushes even if you only have two fans.” Toutiao founder Zhang Yiming himself put forth this line of argument for his flagship product in 2015, stating, “Before, only highly educated elites could produce content. But with the development of technology, the barrier to content production is becoming lower.”11 However, this also caused headaches for our interviewees, as a high number of followers did not guarantee high engagement and views. “Whether an article can be recommended or not is determined by an algorithm, and cumulative fans are useless,” P17, a digital media publisher, explained. “The algorithm is a black box, and Toutiao will not publish its rules. What we can do is to study its rules. For example, the characteristic of the algorithm is that the title is more important than the content. We will consider adjusting the title according to the characteristics of the headline.”

Others spoke about personalization’s ability to explore the needs of more users, readers, and audiences, calling the technology a double-edged sword. P2, a publisher at a state-subsidized media outlet, rejected the depiction of personalization algorithms of commercial media as inherently vulgar, saying: “If you don’t always consume those things, will [vulgar news] come out? … Personalized recommendation itself is harmless, and it cannot be equated with very vulgar content. Watching vulgar content itself is the subjective behavior of users. The algorithm itself is harmless.”

Interviewees from platform companies agreed, saying they see users’ needs are being met, whether they want to acquire knowledge or just pass the time. They do not judge people for their interests. “I know that the public I am going to face is a wider group of people who are more interested in juicy content,” P19, a personalization news aggregator’s brand operations manager, said. As a result, P19 said they recognized they had to cater to their users and asked, “Why is it up to you to say what a user should or should not read? Why do you have the final say?”

Section summary

- Among our interviewees, there was clear acceptance of personalization as a core feature of the Chinese news industry; all publishers and platforms engaged with it.

- Our interviewees understood personalization as implicit personalization built on collected user data and governed by sophisticated algorithms.

- The reasons they provided for the push toward personalization included the proliferation of information, enhanced user targeting abilities, users’ limited attention resources, and the desire for engagement and traffic.

- Although state media are able to sustain themselves with government funding, they look to commercial pursuits to bolster their presence and freedom to make them less dependent on state funding, thus rendering them unable to disregard personalization nor entirely discount the competition from platforms.

- Participants listed myriad problems they saw as by-products of the drive toward personalization, including echo chambers, fragmentation, misinformation, privacy issues, the prevalence of vulgar content, and a changing perception of what news is.

- Others noted the benefits of personalization, including its ability to cater to the needs of users and to level the playing field against the perceived monopoly of traditional media.

Approaches to Personalization

Through their attitudes toward personalization, we see publishers increasingly betting that personalized content will augment user activity and engagement. Publishers have adopted personalization strategies, including building their own operations teams to interface with news platforms and experimenting with personalization on their own apps for relevance and attention, even if they, like party media, did not prioritize revenue generation. Despite the individual concerns our interviewees expressed, the fundamental importance of personalization and the pursuit for traffic were irresistible. Even so, we found publishers to be generally driven by a “news logic of personalization,” an attempt to augment relevance and newsworthiness, in contrast to the “platform logic of personalization,” which emphasized stickiness and advertiser revenue, a bifurcation Balázs Bodó used to describe Western media technologies.34 While this dichotomy also played out among our interviewees, because of the way the Chinese news ecosystem is structured, our participants laid out different and unique considerations that affect their decision-making. This portion of the report will further examine positioning with and against competitors, content versus algorithm, and media regulation.

“The biggest difference is that we are definitely not as good as Toutiao.”

We have discussed the notion that all media groups are practicing personalization to a degree, a phenomenon frequently attributed to Toutiao’s rise to prominence. “Because before it rose up, all of our web clients were not personalized at all,” P5, a push recommendation group leader at a regular news aggregator, said. “Then when Jinri Toutiao emerged, it was completely personalized. Its [Toutiao’s] user engagement time was very long. Even now its user engagement time is longer than ours.”

We also laid out the ways our interviewees believed the news industry has changed as a result. Toutiao’s success has affected the way media organizations approach personalization. “They were a blow to our generation of traditional news apps, especially when the Cyberspace Administration didn’t regulate [them] as much,” P5 said. “And us apps, we were actually hit quite hard by Toutiao.”

Several people mentioned the inability of their apps to keep up with Toutiao. As P15, a traditional media publisher, explained, “There aren’t many platforms that have great impact. Toutiao is the biggest. Sina and Tencent are still behind Toutiao. … Right now, Toutiao is, for sure, the big boss.”

We heard different stories of how news organizations were experimenting with or implementing personalization, sometimes despite interviewees’ individual concerns or emphasis to the contrary. P15 said the traditional mindset of their outlet, a newspaper, meant they had less interest in personalization, but then went on to describe how they had begun hosting other public accounts on their platform in the last two years, thereby emulating Toutiao. “It can be regarded as keeping up with the new trend of the world,” P15 said. Interviewees from state-funded media also detailed their new personalized recommendation channels, many set up in 2019.

However, these changes came with the acceptance of platforms and publishers’ inability to win against Toutiao. P8, a state media app editor, said, “Tencent has a lot of traffic and Toutiao now has a lot of traffic. … There is no professional media organization in China that can match them.”

Several interviewees expressed similar ideas about the tangible technology and popularity gaps between their organizations and Toutiao. One reason given for the difference is the traditional mindset of employees, even at news aggregators. “The chief editors or our editors all think about it,” P13, a regular news aggregator employee, said. “We constantly try to find the balance [between traffic priorities and journalistic values] and try to stick to something akin to traditional media. … I can’t fully embrace personalization.” We found interviewees with journalism backgrounds or training, regardless of their current position, were particularly reluctant about personalization.

It was understood, however, that Toutiao’s success hinged on the vast amount of data it has and its first-mover advantage. In addition, our interviewees saw Toutiao as a technology company and not as a news media platform; therefore it was considered unfettered by a commitment to the same journalistic values and concerns, which allowed it to pursue what is most profitable. We will further explore this notion, and other perceptions of Toutiao, in the next section on news with Chinese characteristics.

“They are platforms, and we [provide] content, but we also have platforms.”

Within China’s news environment, information distribution platforms’ content production and interviewing rights are limited to certain subjects deemed less politically sensitive, including sports, technology, and finance. Some news organizations, especially state-sponsored and traditional ones, were quick to remind us of that fact. “Because of the special nature of China, internet companies do not have the right to interview,” said P2, a state media app editor. “So what aspect of the competition do you mean? They have platform advantages, we have interview and editing advantages, and these advantages are different. If you want to discuss the competition between platform advantage and interviewing and editing, I think there’s no discussion.”

P2 continued, “When comparing traditional media with internet companies, it may seem like you’re comparing the same thing, but actually the dimensions of comparison are different.”

Both regular news aggregators and digital media outlets frequently conveyed the difficulty of comparing their shortcomings to the strengths of others. “I think it’s best to adapt and face it,” P11, a digital media operations manager, said. “My personal view is we have to play to the most unique advantages of our own platform. Instead of saying that I must have what others have, I take my own points to directly compete with others.”

For traditional media organizations, this boiled down to a question of content. As P3, a state media assistant general manager, said, “The whole world does personalization the same way: that is, to make recommendations. You have to have something to recommend. … I think that if there is variety, personalization can be satisfied. Otherwise, personalization cannot be satisfied. For us, we feel that the variety of content is very important.”

At times, it was made clear to us that such content should be “better” and “not the kind that you see on Baidu or on the internet,” as P8, a state media app editor, said, referring to both low-quality and vulgar information. Traditional and state-sanctioned media have an editorial role, we were told, and a job to curate editorially responsible algorithms. “Our algorithm is different from that of pure commercial media, because more weight in our algorithm is placed on the aspects of public welfare and responsibility,” P2 said. “It is the kind of content control that an administrative media should have, and it is not like the traffic-only theory of commercial media.” Other publishers echoed this stance; even regular news platforms emphasized the importance of editorially curated algorithms. “We have stricter controls, because not all content is suitable for broadcasting on our platform,” P8, a state media app editor, said. “After all, we are here as a very important media organization. Toutiao is not like this. As long as you have information, even if you share a cooking video, it can push you to a very important position. But we are different; we have our own media standards.” These standards require content to be strictly screened and to meet the values and requirements of the organization.

In view of the overwhelming amount of traffic news aggregators receive, publishers often understood they could play to their own advantages by providing good reporting. “The main way to increase traffic is through influence and good journalism,” P17, a digital media publisher, said. “Make responsible reports; make authentic reports to make more people believe in your reporting.” However, despite our interviewees’ emphasis on quality journalism and reporting, in the face of clickbait and manuscript washing, good reporting is not necessarily algorithmically privileged.

In light of similar observations for the Western news market, previous Tow Center research asked, “Is publishing going to remain a core activity that supports journalism, or will it, over time, migrate more fully into the fabric of technology and hosting companies?”1 A similar question can be posed for the Chinese media ecosystem, but with an added layer of top-down regulation. Several of our participants laid out the ways they felt they were not in competition with Toutiao or other platforms because of how the news ecosystem is structured. Most publishers acknowledged that competition has to exist on some level because the user’s attention is limited, and, as P12, a state media’s new media editor, said, “the more time he spends on Toutiao, the less time he spends on your product.” However, in terms of content and standards, the inherent positioning of their organizations were set apart from news distributors. In part, this is due to the structuring of commercial versus noncommercial media. “We don’t need to make advertising money through market competition,” P8, a state media app editor, said. “So we don’t have a lot of competitiveness.”

“In many cases, we are actually seeking to cooperate with these platforms.”

From our conversations, it became apparent there was a sizable amount of inter-organizational cooperation between platforms and publishers, resulting in a close and, at times, symbiotic relationship. The biannual report on internet development in China noted how traditional media has actively sought to strengthen cooperation with “information aggregation and entertainment content platforms and accelerated their integration into the online content ecosystem,” while platforms valued the same partnership for the content opportunities it provided.8 Some state media mentioned platforms providing technology and expertise to them, including building the operating system for the state media’s own venture into platform news. Other organizations described having designated staff responsible for liaising with platform representatives. “Our operations guy will communicate with the editors of larger media platforms,” P15, a traditional media publisher, said. After discussion with the platforms, the platforms may opt to put the content in a more advantageous position. “You can dance with these platforms,” P15 continued. “Both parties get benefits and maintain a long-term cooperative relationship.” All news publishers, we learned, had operations teams with dedicated staff to target content toward specific platforms, and manage relationships with them.

As P12, a state media’s new media editor, put it, it is a question of achieving the effect of one plus one equals two rather than of simple competition. “Why can’t we all play to our respective strengths? Compared with us, commercial media is like internet companies. Their most dominant point is technology. Our most dominant point is content. If we combine our strengths with their strengths together, isn’t that a one plus twelve effect?”

Not everyone we spoke to was as optimistic about the collaborative nature between platforms and publishers. As previously indicated, we heard several misgivings about personalization that have been pushed aside in pursuit of traffic, and the perception of an inability to win against Toutiao or turn the tide of an irreversible trend. “After media was forced to become new media, I think what many media are doing is working for platforms,” P15, a traditional media publisher, said. “We cannot compete with them, but they do deprive us of channels, because they have a huge export, and we can only spread our things based on their ecology. But there is no other way. It can only be this way, because now you really don’t have good channels. We can say that there is no competition with them, because there is no way to compete with them.”

“News about General Secretary Xi Jinping in Toutiao has always been at the top.”

Several factors stood out during our interviews as influences on our participants’ decision-making processes, separating into three overarching approaches to recommending news: manual intervention, subject to the decisions of an editorial department; news articles based on the activity of your social circles; and algorithms. Among news institutions with traditional leanings, interviewees spoke frequently of prioritizing news value and quality, which was work that could only be done by humans; however, none argued against using personalized algorithms as the most efficient way to promote reader engagement, while manually editing content was the lowest. As P9, a regular news aggregator’s push recommendation manager, put it, “We rarely intervene manually, because you will find that once manual intervention is performed, the data will fall.”

However, P9 was quick to say that they essentially use algorithms to push their content “except for the articles that need to show on top,” thus demonstrating a level of human intervention that is integrated into China’s news governing structure. Even personalized news aggregators are beholden to these rules, which results in the tendency across all our media categories to mix the three approaches of human intervention, social circles, and algorithms when it comes to their news recommendation strategies. As P7, a personalized news aggregator’s editor-in-chief, summarized it, there are two steps underlying their internal process: “The first is to make the distribution efficiency and click-through rate higher. The other is to follow the basic principles of correct values. In short, there must be some ideological things in it. The ideological aspects are realized through the intervention of the chief editors.” Top-down regulations from the Cyberspace Administration dictate these correct values, thus providing the framework within which all publishers and platforms must operate, which means the algorithm must be more editorially responsible as well. “If you don’t believe me, try to write some [high-quality] content, but if you are anti-Party and anti-socialist, it will be killed immediately,” said P7. “This is a matter of values. So the algorithm has to learn how to understand the variables including the political left, middle, and right.”

Aside from media regulations, such intervention is necessary for traditional and digital media, as we have previously examined, in part because they see personalized algorithms as tied to lower standards of news and vulgar content. This was also because platforms were limited by what original content they could create as a result of media control. “This change was mainly brought about by the Cyberspace Administration,” said P5, a push recommendation group leader at a regular news aggregator. “They don’t let us create anymore. So now we basically don’t have original content, or very few—just in the fields recognized by the Cyberspace Administration. The areas where we can create original content are finance, and technology, and sports. Yes, finance, technology, and sports are what [the Cyberspace Administration] thinks we can do, and the rest are not original content, but they used to be.”

We look further into media control in the third section of the report, examining news with Chinese characteristics.

“It must be the kind of things that can be understood by the elderly and children in the streets.”

The final component many of our participants felt was a key concern was the demographic of their readers. Some organizations had clear target audiences, while others tried to appeal to a broader user base, but ended up falling short.

From state-sponsored media to regular news aggregators, these interviewees delineated the difference in accessibility and popularity of their platforms versus Toutiao’s platform. We heard these publishers underscore the importance of market segmentation and accept their inability to please everyone, something they perceived as different from Toutiao, as Toutiao could grasp individual preferences or attract people regardless of age, class, and gender. This was not necessarily viewed as a negative factor by our traditional and digital media interviewees, who saw their news curation as targeted toward a more educated audience. “The content is more in line with the needs of this group of people,” P6, a state media app editor, said. “Mainly people with relatively high levels of [education].”

In contrast, personalized algorithms, along with the perceived vulgar content they brought, were linked to appealing to the tastes of a larger, less well-educated group of Chinese internet users. “Our product must have a particularly low threshold, and users will only like it if the threshold is very low,” said P5. “And you must interact with them to make them think that you are not superior. They don’t like the kind that is better than them, superior to them, and talks down to them.”

Only 19.5 percent of Chinese internet users hold a university-level education or higher.8 Consequently, the staff we interviewed felt they had to cater to the less-educated majority. While we previously noted that some of our interviewees described the positive ability of personalization to cater to user needs, others who worked at news aggregators expressed the way their demographic considerations frustrated them and limited their approach. “You have to bend down to study and hug these middle- and lower-level users and young users,” P13, a regular news aggregator employee, said. “Because they are the most important users of social media and new media now, I have to consider them.”

Section summary

- Jinri Toutiao’s emergence has affected the way media organizations approached personalization, motivating other publishers and platforms to experiment with and implement personalization.

- The inability of most organizations to reach the same level of personalization as Toutiao was understood as primarily due to Toutiao’s first-mover advantage, their own media positioning, and professional standards.

- Publishers emphasized the advantages they had against the overwhelming traffic enjoyed by platforms, listing the importance of good journalism, variety of content, and stricter standards for what passed as news, while platforms were limited in their content creation privileges and subjected to other regulatory scrutiny.

- Publishers rely on platforms for traffic, and platforms turn to publishers for content, resulting in a relationship characterized by cooperation and competition.

- Government regulations insist upon a level of human intervention, with the required addition of pinned, standard news content of political importance, rendering even personalized news aggregators unable to disregard manual intervention and curation.

- Our interviewees perceived a divide between the audiences of news publishers and platforms, with the former comprising a better-educated group. Some expressed frustration that, due to the makeup of the Chinese internet, appealing on a mass level meant appealing to a less well-educated majority.

News with Chinese Characteristics

Previously, we delved into the drive for personalization affecting all of our interviewees across all types of media organizations. However, the nature of China’s political setting alters and obstructs the digital news landscape. This section explores both the ways our interviewees are limited, and the consequences of the interconnectivity between platforms and publishers.

“A defining attribute of Chinese news: I feel like it’s that there’s a bit more oversight.”

State control over media and information tools in China has intensified in recent years, resulting in particular consequences for different news media types, including the barrier to content creation faced by platforms that we addressed in the previous section. “Internet companies like us are very obedient now,” said P5, a push recommendation group leader at a regular news aggregator, said. “This was very different just a few years ago. And now if we want to do something, we have to anchor ourselves to party media.”

The majority of participants mentioned media regulation and control when asked about defining characteristics of China’s news market. Some danced around the issue, only briefly alluding to the political association their organization had to the Chinese ruling party. P2, a state media app editor, said, “We may be relatively more efficient in administration (行政 “xingzheng”). Do you understand my wording?” Other publishers accepted media oversight as an intrinsic part of the Chinese news industry, while others still saw it as no different than standard media regulation in other countries. “In the Chinese context, there is just some content that has to be done away with or has to be banned,” said P14, a web product manager for a digital media company. “It’s just that the line in each country is different, or your taboos are different. There is no speech that is completely uncontrolled.”

Regulation is built into the fabric of the Chinese news ecosystem and has become more all-encompassing over the last decade. News platforms particularly have come under heavy scrutiny and control in the last few years, with consequences ranging from sections of Toutiao’s apps frozen for 24 hours; news platforms removed from app stores; platforms required to hire thousands of censors to oversee content; and opinion articles published in party media condemning algorithmically driven news apps for superficial content and misinformation.35 “I think the biggest feature is that China inevitably cannot circumvent a party-oriented issue,” P12, a state media’s new media editor, said. “Therefore, it is difficult for us to discuss news issues from the viewpoint of the news market and news consumption, especially in recent years when we’re discussing these things with ‘Chinese characteristics.’ On the contrary, a word like ‘news market’ is not heard of much now.”

The most noticeable way state control is manifested is through standard content pinned to the top of front pages and app interfaces, something Toutiao also must abide by (Figure 2). We heard a variety of stories from regular and personalized news aggregators about notices from the Cyberspace Administration of China denoting sensitive words that must not appear, information that should be downplayed or hidden during important events, and news items that must not be pushed or recommended. These directives frequently arrive without warning and can change at a moment’s notice. Elaborate mechanisms of self-censorship are required of media technologies to navigate both formalized and quasi-formalized hidden rules, including internally hiring thousands of censors and checking content multiple times before publication. ByteDance currently employs 15,000 censors, according to the latest figures given to our researchers. Digital media outlets and aggregators also detailed how they label content from party and other large traditional media outlets to prioritize it. Government efforts to sanitize the internet have also led to technological interventions involving protecting minors, removal of sexual and violent content, and internet addiction. “Compared to media in foreign countries, I think this point might be a little more unique,” concluded a state media journalist.

“The average user thinks, ‘I read it on Toutiao, then it’s Toutiao who provided the news.’ They don’t care.”

Between the traditional media, who look down on platforms but cannot resist the enticement of traffic and user engagement, and the aggregators, who are popular, yet need content and are beholden to party regulations, there are a lot of blurred lines and interconnectivity between news producers and distributors. The increase in inter-organizational cooperation has deepened the platformization of media with traditional leanings, the intermingling of news and entertainment, and the muddling of news brands. In private conversations, academics discussed the outdatedness of using traditional definitions of “media” to describe even the People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s mouthpiece, when its new media department spent time holding public welfare concerts (for graduates during the epidemic, for instance), planning museum exhibitions, and organizing activities around major news events. These activities are mainly accomplished through cooperation between the People’s Daily and third-party technology companies. For example, the Time Museum, which commemorated the 40th anniversary of reform and opening up, was planned and executed by Beijing Broadview Information Technology Co., Ltd., or Broadview Consulting for short. Clearly, all news organizations are affected by the push to expand and integrate online content, but our researchers still observed the disparity between the editorial mission (and political missions) of publishers and the commercial objectives of platforms. In other words, publishers are driving up personalization, increasing their reliance on technology companies, and upping their entertainment value in pursuit of relevance, attention, and propaganda or publicity impact. Similarly, government-run accounts are appearing across Chinese platforms for propaganda outreach, with close to 83,000 accounts on Toutiao and more than 17,000 creating short-form video content on Douyin (the domestic version of TikTok).8

Blurred boundaries between information and entertainment, platform and publisher, and professional and user-generated content have resulted in a versatile digital landscape. Our interviewees thought one characteristic of the Chinese news environment was the more “modern,” or technologically sophisticated, ways domestic users receive news. This was especially apparent for our participants when they viewed news media in the United States and Europe. “I feel that for some Chinese marketing, there are many tricks to get new users and promote user stickiness,” said P10, a personalized news aggregator’s push recommendation editor. P5, a push recommendation group leader at a regular news aggregator, brought up the New York Times and other traditional media for comparison: “They are also working hard to do new media or doing apps themselves, but … it’s impossible for them to reach our heights.” This was attributed to various reasons including a vast amount of readily available data, micro-innovations as a result of competition, and cooperation among media organizations that has integrated and expanded distribution methods and content variety. “I think Chinese products have many more ways to play,” P10 concluded.

The popularity of news distribution platforms, which aggregate various sources of news and house a plethora of accounts that upload both professional and user-created content, has, however, led to a sharp loss in news branding. “When users read a headline on Toutiao, they wouldn’t pay attention to where this article came from,” P16, a digital media reporter, explained. “Only other media organizations would care.”

A number of publishers working at traditional and digital media outlets reported that they are frequently told by users, “Who reads your newspapers? Every day, we now read the news on Jinri Toutiao.”

“The news items on Jinri Toutiao are our news items and our content, but they don’t know that,” P15, a traditional media publisher, said in frustration. “The average reader doesn’t know that. They believe it’s Toutiao that provided it to them.” In response, our interviewees engaged in practices including placing content behind subscription-based paywalls and building out their presence on other news and social media platforms; however, they felt these methods were inadequate to counter the loss of brand recognition, especially in the face of rampant manuscript washing.

This interconnectivity also meant our interviewees seldom agreed on who had more clout within China’s news ecosystem. Some, again, emphasized the traffic and engagement that platforms enjoy. “The Chinese news market has a pretty distinct feature,” P5 said. “The organizations that produce news are relatively powerless, while the platforms that spread news, platforms like ours, while they do not produce news themselves and just spread news, these platforms are powerful. Because basically, the user’s time and the user’s attention are all pulled in by our platform-based products.”

However, several platforms expressed frustration at having to anchor themselves to party media and regulation, who held what they saw as a monopoly over official news, leaving aggregators unable to cover important current affairs. We saw this dynamic play out as we interviewed our participants during COVID-19, something we’ll touch on in the next section.

“Toutiao doesn’t care about news. It cares about quality content to keep users on their platform.”

All news organizations in China find themselves directly and indirectly enmeshed with third-party platforms. No news media is unaffected by the drive toward personalization. However, other publishers and platforms do not appear to hold Toutiao accountable for the health of the news industry. Certainly, the government’s censorship apparatus will occasionally accuse ByteDance and other platforms of harming journalism; however, such directives are often tinged with political motivations. While our participants expressed similar concerns about vulgarity and misformation and saw Toutiao as an active participant within the news ecosystem, this never translated to calling on the news aggregator to take responsibility in the way Facebook was after the 2016 US election.

Instead, those we talked to made it clear that Toutiao was a technology company. Some publishers stated that they weren’t worried Toutiao would replace certain media organizations because that was not the news aggregator’s expressed intent. Several said it should be considered more as a content aggregator than a news aggregator, featuring not only news, but also videos, livestreams, and games. ByteDance has also expanded to TikTok after acquiring Musical.ly, Faceu, and Flipagram. The company is seemingly interested in building up a chain of entertaining content, rather than necessarily providing news, a tendency that was clear when CEO Zhang Yiming, who has a background in technology and not in journalism, described Toutiao as the internet plus personalization. This isn’t isolated to Toutiao, as other PNAs have also said their distinguishing feature is their personalized recommendation algorithms and not news. In addition, while industry professionals and Chinese academics understood Toutiao’s effect on the Chinese news industry, they also considered Toutiao and other news aggregators “informational distribution platforms,” rather than news platforms, and not beholden to the same values and responsibilities as news publishers.36

One reason for these attitudes, we were told, might be that algorithmically driven content is so pervasive it has become larger than the responsibility of specific platforms or publishers. The algorithm itself must be restrained, improved, or altered. Others noted how regulatory bodies exist to curb the actions of platforms. Several mentioned the effect of this media control, with platforms stating they are now more “obedient” and less “wild” compared to a few years ago when there was less oversight. However, this same regulatory body has caused the decline of journalism’s independence by putting pressure on and increasing censorship demands for investigative reporting, journalists, and news organizations, leading to media that, first and foremost, serves the Party. Moreover, our interviewees said the problems they see, including manuscript washing and sensationalism, have been common since the rise of the commercial internet and exacerbated by China’s ineffective copyright protections, all of which existed before Toutiao. Some specifically pointed to news portals like Tencent as among the first to fragment the news sphere during the digital transformation process.