This report is part of an ongoing, multi-year study by the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism School into the relationship between large-scale technology companies and journalism.

The findings are taken from a combination of two years of original data collection, over a hundred interviews with journalists and platform executives, and three in-depth workplace studies. Results from a newsroom survey of 1,100 journalists undertaken on behalf of the Tow Center by API /NORC are also included in the study.

This research is generously funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Open Society Foundations, John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Abrams Foundation, and Craig Newmark Philanthropies.

Executive Summary

By Emily Bell

The relationship between technology platforms and news publishers has endured a fraught 18 months. Even so, the external forces of civic and regulatory pressure are hastening a convergence between the two at an accelerated rate beyond what we saw when we published our first report from this study, “The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley Reengineered Journalism,” in March 2017. Journalism has played a critical part in pushing for accountability into the practices of companies such as Facebook, Google, and Twitter, yet newsrooms are increasingly oriented toward understanding and leveraging platforms as part of finding a sustainable future.

In the latest phase of our multi-year research into the relationship between platforms and publishers, we found that despite negative rhetoric and sentiment in newsrooms toward technology companies, there is a rapid and ongoing merging in the functions of publishers and platforms, and an often surprisingly high level of involvement from platform companies in influencing news production.

Technology platforms that host, monetize, and distribute news are attempting a “pivot to civics,” pushing them further into the traditional territory of news publishers as they provide more direct support for journalism and develop larger teams of editors and moderators to shape content. We’ve seen extensive and well-documented efforts to fight against a narrative that has placed them as squarely to blame for a series of failings in the information ecosystem. Platform companies have become more explicitly editorial in their own practices and structures, whether by reverting to more human “curation” of stories and feeds, or in the case of Apple News, publishing its own “exclusive” content from a newsroom staffed with writers and editors.

The perceptible change in strategy among these companies was precipitated by the spread of misinformation, scandals involving the misuse of personal data, and an ongoing funding crisis in journalism. But as technology platforms lean into the role of publisher, and become more enmeshed in the journalistic ecosystem, news organizations are showing signs of pushing back with strategies that help them retain some autonomy and control over their destiny.

In 2017 and early 2018, a series of damaging revelations highlighted the poor governance and ill-preparedness of technology companies such as Facebook, Google, and Twitter to fulfill their roles as gatekeepers of the news and information environment. From the circulation of Russian propaganda during the 2016 US presidential election campaign, to the misuse of Facebook users’ data by Cambridge Analytica, the dysfunction in the design of social media platforms and business models is now central to global policy debate.

The Tow Center research project into platforms and publishers follows the contours of this new dynamic insofar as it relates to the production of journalism. The picture for both platforms and publishers is mixed. While news organizations are just as engaged with social media as ever, we see strong signals that they are adopting a more discriminating approach to platform use, favoring bringing audiences back to their own properties over “social first” publishing.

Platforms’ mercurial behavior, and rapid changes to their own businesses, make formulating long-term strategy for publishers nearly impossible. The Tow Center has long been tracking decisions by platforms that affect publishers, from policy and product updates to monetization opportunities. We’ve observed over 600 developments in the course of our research that have, in some cases, resulted in costly outcomes for publishers. Facebook’s tendency, in particular, to frequently update and launch new products, and tweak the algorithms which surface content on its News Feed, are fatiguing publishers.

And yet, our survey data from journalists across 1,025 unique newsrooms in the United States and Canada—with 94 percent of respondents working in news outlets considered to be local—suggests that the vast majority of organizations have taken steps to adapt to this social-mediated news environment. Four in 10 journalists (41 percent) say their newsrooms have made major changes to how it produces news in response to the growth of social media platforms. About an equal share (42 percent) say their newsroom has made minor changes. Just 15 percent believe their newsrooms have made no changes to their news production routines.

At the start of our interviews in early 2016, publishers spoke about platforms with more detachment than they do today; they were distribution channels to put content in front of audiences. But in interviews conducted over the past six months, both platforms and publishers repeatedly used words like “partner” and “partnership” to describe their increasingly close relationship. We have been consistently surprised by how much newsrooms discuss with platform teams—in some cases, this includes budgets, workflow, and even the content of as yet unpublished stories. One large publisher described the evolution this way: “Now it’s becoming, ‘how do we collaborate on new products? How do we do co-sale things together?’”

This evolving partnership is unequal, however. Platforms wield more power over formats and data and earn more advertising dollars than publishers, even as platform choices increasingly inform publishers’ editorial and distribution strategies. For example, in May 2017, Apple hired its first editor in chief to oversee other Apple newsroom personnel who curate content alongside its algorithm. One news publisher told us, “We’re on Slack with the Apple editors every day. We’re pitching stories. They know what’s coming from us. They know our budget.”

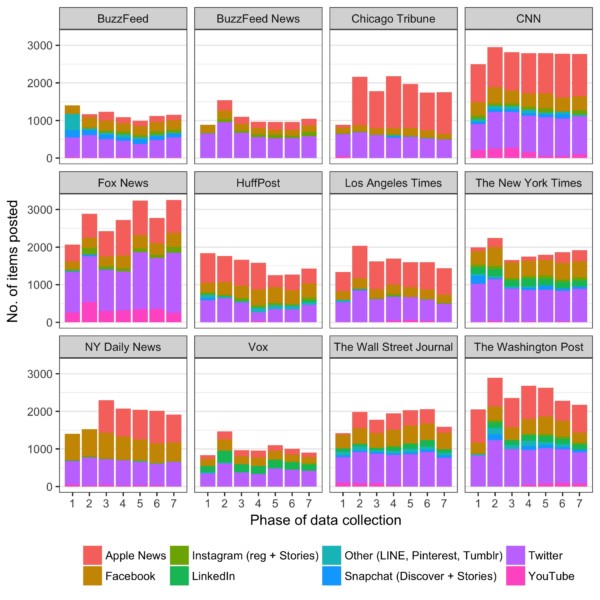

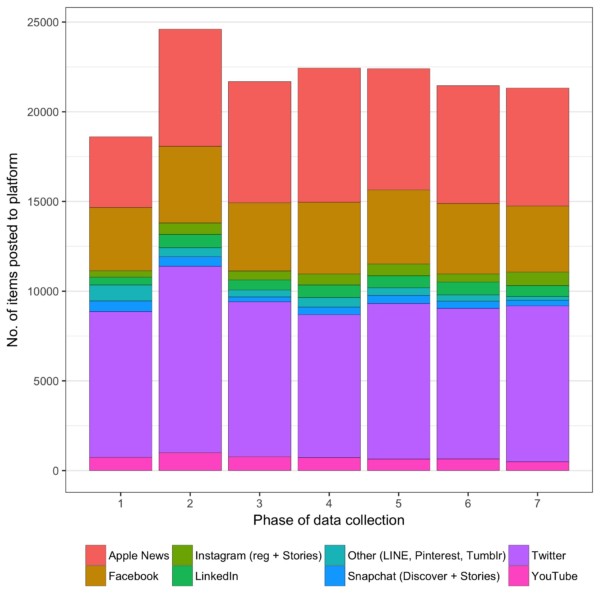

While our interviews highlight the various misgivings that publishers have about relinquishing control over the publishing process to tech companies, our data suggests that publishers continue to post their content to social platforms at high volume. In tracking the platform use of 12 major publishers, the amount outlets posted to 14 platforms remained remarkably consistent over our 18 months of analysis. The total number of items posted hovered around 22,000 during each of seven, weeklong analyses, accounting for an average of 1,800 items per publisher.

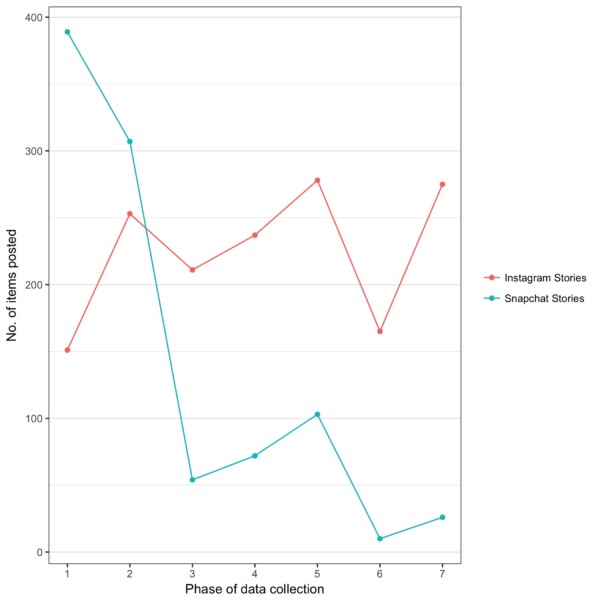

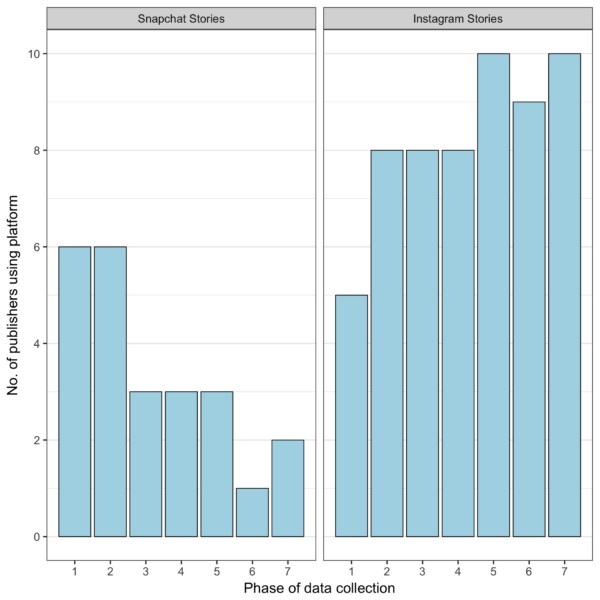

We did, however, observe some consolidation in platform use, with the use of Snapchat stories declining, and Instagram (owned by Facebook) strengthening its hold on visual storytelling. The highest volume of content posts among the 12 news outlets we studied went to Apple News, Facebook, and Twitter. Medium-volume platforms included Instagram, Instagram Stories, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Snapchat Discover, Snapchat Stories, and YouTube.

Simultaneously, technology companies—most notably Facebook, Apple, and Google—have increased initiatives around more direct means of supporting journalism. Initial efforts by platforms to offer advertising opportunities through their own products have declined and been replaced by both small injections of resource and money, and the development of subscription products for publishers. As news organizations currently see the key to survival as diversifying revenue streams both on and off social platforms, the most important of those streams is reader revenue. This can include events, paid subscriptions for publishers with paywalls, and membership and donation revenue for publishers who want to keep their journalism open. Platforms by and large say they are trying to find ways to accommodate publishers, but never at the expense of their own relationship with their users.

Our key findings from this phase of research are:

- According to a survey of over 1,100 working journalists conducted in partnership with API and NORC, journalists have a conflicted relationship with social media. While the vast majority of journalists said they had adapted practices in the newsroom in response to social platforms, an overwhelming number (86 percent) felt that social media had contributed to a decline in trust in journalism.

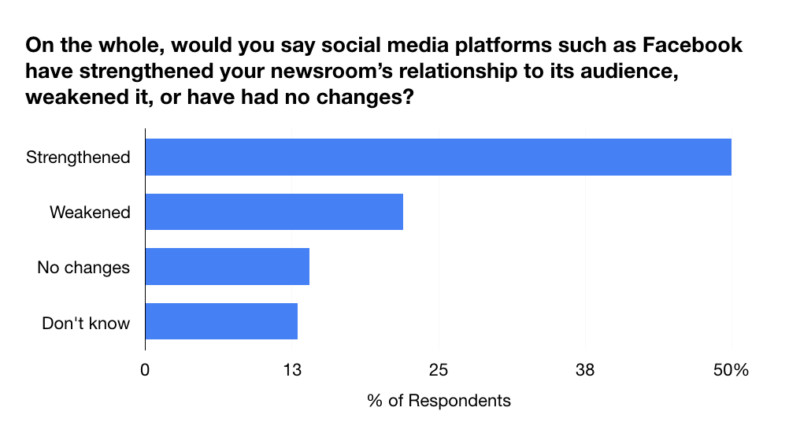

- Half of the survey respondents said social media platforms (such as Facebook) strengthened the relationship with their audience, while 22 percent said it had weakened as a result of social media platforms; 56 percent of respondents said platforms should take “a great deal/quite a bit” of responsibility for financially supporting journalism; and 76 percent of respondents said that Facebook wasn’t doing enough to “combat the problem of fake news and misinformation” on its platform, while 71 percent said the same about Twitter, and 65 percent about Google. Facebook consistently drew the strongest criticism from publishers in all areas of our research.

- Despite the apparent toxicity of the rhetoric toward technology companies in general, and Facebook in particular, this did not appear to diminish the amount of material publishers directed through social platforms. We have, however, seen a sharp adjustment from publishers away from creating material which lives entirely on third-party platforms. As publishers practiced a “conscious uncoupling” from social media’s influence, platform companies have intensified their own efforts to remain involved in shaping the future of journalism. Whether this is a long-term strategy or a public relations initiative remains to be seen.

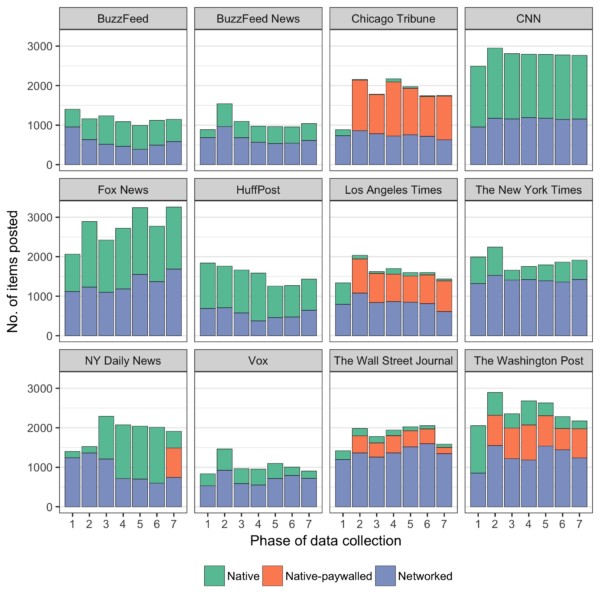

- Of the 12 news outlets we tracked over an 18-month period—CNN, Fox News, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, New York Daily News, BuzzFeed, BuzzFeed News, HuffPost, and Vox—the larger, better-resourced publishers consistently posted more content to a greater range of platforms. The smaller outlets were almost entirely focused on Apple News, Facebook, and Twitter. This was particularly pronounced at the three regional metros, the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and New York Daily News. By the time of our final analysis, in March 2018, just one percent of posts made by these three local publishers went outside of Apple News, Twitter, and Facebook.

- Larger publishers still have more access to platform partnership teams and product offerings than smaller and local publications. Local news publishers, in particular, have been hit hard by the loss of advertising revenue. It’s becoming clear that attempting to translate the advertising-driven business model of news publishing from print to digital by posting high volumes of content to social platforms and adopting platform-native products like Facebook’s Instant Articles—which more than half its original partners abandoned once payments to use it ran out—has been a failure. Newer efforts by technology companies, especially Facebook, to help local journalism have borne little fruit, and in some cases have been counterproductive. For instance, even the Facebook News Feed algorithm change announced in January 2018 to prioritize interactions with local news caused a steep drop off in some outlets’ website engagement figures.

- Platforms continue to shape both the style and substance of publisher content, either directly with financial incentives (Facebook has offered publishers substantial advertising credits on its platform to participate in product rollouts), or indirectly (Apple accepts pitches from publishers seeking to be featured in its news app). There are no signs that this will change. Since news broke in late 2017 that both Apple and Facebook had one-billion-dollar budgets for original programming, with Facebook reportedly offering three to four million dollars per episode of new programming and Google-owned YouTube offering two to three million dollars for the same, there has been a distinct pivot toward creating video content among the most well-resourced publishers we interviewed. One publisher told us that platforms are looking toward more “Netflix-style” deals and treating publishers like production companies.

- Current platform strategies toward news publishing are being shaped less by market forces and more by a mixture of civic duty and fear of regulation. This is leading to the adoption of much more explicit “editorial” practices, including hiring more newsroom journalists and human moderators, and active engagement in other strategies to elevate “higher-quality” news. This will inevitably lead to technology companies having an even greater influence in deciding which news publishers benefit from the environment, and what news consumers see in their feeds and search results.

- Major concerns persist over the opacity of algorithm changes, the control of the relationship with audiences, the financial support for smaller-scale journalism, and promotion, deletion, or suppression of different types of news stories.

- We anticipate much more investment from platform companies in curation, whether human or automated, and more resources directed at journalism practice. One unexpected outcome of the past two years of revelation and public debate about platform roles in news has been an expeditious cultural shift within the companies themselves.

Our research suggests that negotiations between platforms and publishers have become more mature and realistic. As the platform press grows up, however, there is still an insufficiently stable environment for a consistent supply of news at all levels. And there remain a number of outstanding issues about the power and opacity of technology companies.

While the latest earnings reports from Facebook, Twitter, and Google don’t indicate financial implications, and in fact exceeded expectations in the first quarter of 2018, we may be entering an era of reckoning for platform power. It’s becoming obvious that platforms cannot scale advertising revenue in tandem with the robust intervention needed to ameliorate the type of material they publish. Hate speech, fraudulent material, deliberate propaganda, and misinformation all grew largely unchecked in an environment where platforms did not police the content they hosted with enough rigor.

Important as it is for the business relationship between platforms and publishers to reach equilibrium if journalism is to have a sustainable future, it is not the only concern. The part platforms play in deciding how news should be distributed and their decisive role in qualitative questions about news production face a severe global challenge. As techniques for fabricating, editing, and reframing news in harmful ways develop faster than they can be detected and countered, journalism and technology companies have a strong mutual interest in finding solutions. The health of democratic debate and process rests on their ability to do so.

Introduction

It’s fair to say that platforms officially began targeting news publishers and their content as early as January 2006, when Google launched its news aggregator, Google News. (The product, however, had been in beta since 2002.) Six months after its public rollout, a Google senior vice president emailed a video presentation to the company’s CEO, Eric Schmidt, and its co-founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, that stated the following: “Pressure premium content providers to change their model towards free,” citing a model based on a “play first, deal later” around “hot content” and the ability “to coax or force access to viral premium content.”

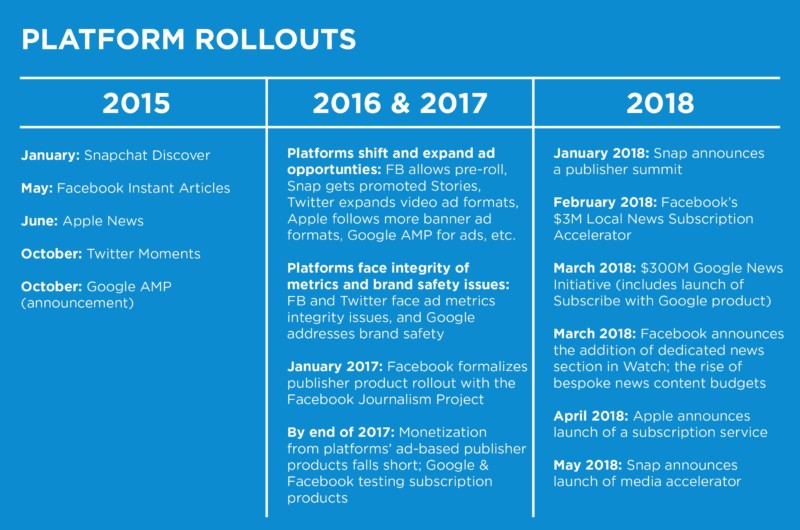

Fast-forward nearly a decade to 2015 and platforms had fully pivoted toward collecting as much news content as possible into their ecosystems. Beginning in January 2015, Snapchat launched its Discover feature, which acts as an in-app magazine rack allowing publishers to deliver Snapchat-specific editions to users. This was shortly followed by the introduction of Facebook Instant Articles, Apple News, Twitter Moments, and, in December, the announcement of Google’s Accelerated Mobile Pages—a product similar to Instant Articles which rapidly loads a publisher’s stories for mobile users reading on Google. Platforms were no longer just places for publishers to distribute content in hopes of driving audiences back to their sites. They were now home to vertically integrated publishing products through which publishers could directly monetize audiences by placing ads against their news content on platforms.

Since publication of our first report from this study in March 2017, during which time the spread of misinformation and rising platform influence over editorial were key issues, publishers have fully moved into platform ecosystems. In “The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley Reengineered Journalism,” Tow Center Director Emily Bell and former Tow Center Research Director Taylor Owen concluded that a “convergence” between platforms and publishers was yielding unintended consequences. Journalism with high civic value—that investigates power or reaches underserved and local communities—is “discriminated against by a system that favors scale, shareability, and algorithms to sort and target content,” they wrote. Still, publishers continued to push more of their journalism to platforms despite no guarantee of consistent return on investment.

The “critical dilemma” publishers were facing then was: “Should they continue the costly business of maintaining their own publishing infrastructure, with smaller audiences but complete control over revenue, brand, and audience data? Or, should they cede control over user data and advertising in exchange for the significant audience growth offered by Facebook or other platforms?”

Over the last year, we’ve seen a continued increase in concern among publishers around their failure to reclaim advertising revenue vital to the news business, crafting long-term strategy amid changing platform priorities, and data privacy—especially as proof emerged that Facebook, Google, and Twitter fostered election-related meddling by Russian actors. What this means for the viability of journalism and civic participation, and who controls both, is at stake.

Methodology

The Platforms and Publishers research project, conceptualized in the late summer of 2015, began in November at Columbia University with the daylong event “Journalism + Silicon Valley.” At the heart of nearly three years of study are two research questions motivating our work: what is the current relationship between social platforms and publishers, and how has it changed newsrooms, platform companies, and audience news consumption to date? What are the future implications of this relationship?

Our deep interest in these pressing issues led us to devise a proposal for a multi-year project looking into the relationship between journalism and platforms with the aim of promoting mutual understanding and best practices for conducting journalism on the social web.

We hope to provide news publishers and journalists with a more granular understanding of how journalism and independent publishing are affected by integration with platforms, and make explicit how platform companies are having to adapt to a new role.

Interviews

Between early 2016 and early 2018, we conducted 109 interviews with individuals from 44 news organizations (representing both national and local legacy outlets, local digital, digital-native, broadcast, audio, and magazine newsrooms), six platform companies, and three industry experts. These interviews were carried out primarily over the phone, lasting 30 to 90 minutes, and were tape-recorded and transcribed. Interviewees were promised anonymity and confidentiality, and guaranteed that their responses would not be identifiable in the final results. The conversations were semi-structured, and centered mostly around editorial and revenue-related platform strategies. Because the focus of this research was publisher reactions to the evolving platform ecosystem for news, the bulk of our interviews were conducted with publishers. (See Appendix III for a detailed breakdown of interviews by type and timing.)

For the purposes of this research, we define a publisher as any organization that regularly publishes accounts and analyses of current events using a staff of journalists and editors. The size and reach of publishers in our sample varied (hyperlocal, local, regional, national, or global), as did their production formats (print, audio, video, digital-native, or platform-native) and revenue models (membership, subscription, or advertising).

We use the term “platform” to refer to technology companies which maintain consumption, distribution, and monetization infrastructure for digital media—though each is distinct in its architecture and business model. Google, for example, is a search engine, while Facebook is a social network. In both cases, the majority of each company’s revenue comes from advertising. Meanwhile, Apple makes money from hardware sales, proprietary software, licensed media, and hosted apps. All have used their technology, however, to create products for news publishers to find audiences and monetize readers within their own ecosystems. Our interviews with publishers focused primarily on Facebook (and Instagram), Google (and YouTube), Twitter, Apple, and Snapchat.

Data analysis

In an attempt to track the evolution of news outlets’ distributed content strategies, we conducted quantitative analyses of 12 publishers’ posts to 14 platforms from August 2016 to March 2018, approximately once every three months in weeklong phases.

Our content analysis was designed to include news outlets of diverse types, covering legacy broadcasters (CNN, Fox News), legacy national publishers (The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post), legacy regional metros (Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, New York Daily News), and digital natives (BuzzFeed, BuzzFeed News, HuffPost, Vox).

Data about the volume of posts made to the following platforms from each publisher’s main brand account (e.g., @cnn, @nytimes, etc.) was gathered over one-week periods, seven times: Apple News, Facebook, Instagram, Instagram Stories, li.st (formerly The List App), LINE, LinkedIn, Messenger, Pinterest, Snapchat Discover, Snapchat Stories, Tumblr, Twitter, Vine, and YouTube. The beginning dates of the weeklong data collection periods were: August 8, 2016; November 7, 2016; February 6, 2017; May 8, 2017; August 14, 2017; November 13, 2017; and March 28, 2018.

Where possible, data was gathered via the platforms’ own APIs. For platforms or products that did not offer public APIs (e.g., LinkedIn, Facebook Instant Articles, Apple News, Snapchat, Instagram Stories), data was either scraped via websites or collected manually.

Workplace study

In parallel to our interviews and quantitative data analysis, we also conducted a workplace study on how platforms are impacting the workflows, roles, and organizational structures of newsrooms. We studied three newsrooms in depth, interviewing 20 people in platform-related roles between January 2018 and March 2018. These interviews were carried out via video conference or in person. Supplementary interviews by phone were conducted with an additional three executives at three newsrooms in February and March 2018 to get a sense of variations in organizational structure by ownership type.

We drew on workplace-related interview material from an additional 18 interviews conducted in 2016 as part of a larger, forthcoming study (to be published independently) for a sense of how the context of platform roles had changed. Our analysis paid particular attention to the dynamics of bridge roles—the people who work in between business and editorial functions in groups like audience engagement, social media, and product. It’s these people who are often in the position to notice, interpret, and implement changes in social platform functionality.

Journalist survey

The Tow Center developed a questionnaire in consultation with the American Press Institute, which was used by NORC at the University of Chicago to conduct a survey across local and national newsrooms in the United States and Canada focusing on journalists’ perceptions of platform companies and their relationship with them. Spanning six weeks, between March 1, 2018 and April 12, 2018, there were 1,127 respondents to the survey from 1,025 unique newsrooms across multiple media outlet types (local newspapers, local TV stations, magazines, digital-only, etc.). Ninety-four percent of the respondents were working in news organizations primarily considered to be local, with the rest from national outlets. All survey respondents had roles in the newsroom, including (but not limited to) as editors, reporters/writers, producers, and hosts/anchors. The topline findings and detailed methodology are available in Appendix II of this report.

Focus groups and policy exchange forums

As part of this research, we also ran a series of focus groups with news consumers in four cities to explore the changing context of consumption behavior, and whether and how the shift to social distribution is being registered as a concern among news audiences. Focus groups were attended by 58 residents from Bowling Green, Kentucky; Elkhart, Indiana; New York, New York; and San Francisco, California. Among the key findings were that audience members often had simplistic and/or inaccurate understandings of the algorithms that surface news on tech platforms; they felt local news was often less visible in their news feeds; and audience members intrinsically linked fake news to social platforms.

In addition, the Tow Center convened four policy exchange forums aimed at examining the emerging implications of social distribution for four areas of publishing policy and technology: artificial intelligence, advertising, content moderation, and archiving. During these sessions, participants representing both the platform and publishing sides of the news industry engaged on issues related to the ethical and civic values of journalism. The forums were closed, by invitation only, and followed the Chatham House Rule providing anonymity to speakers. The summary of findings from the first two were published independently, with the others forthcoming.

State of an Uncomfortable Union: The Platform-Publisher Relationship

Platform companies are now at the core of every stage of the publishing process, from newsgathering and editorial strategy, to distribution and communication with audiences, to monetization. This marks a qualitative shift from when our study began.

From distribution to product partnerships

At the start of our interviews, in early 2016, publishers spoke about platforms with more detachment than they do today: these were distribution channels to put content in front of audiences. The sentiment worked both ways. At the Tow Center’s “Journalism + Silicon Valley” conference in November 2015, Facebook’s then-product manager for Instant Articles, Michael Reckhow, said, “We think of our readers as the customers we want to serve with great news—and then with publishers, we also treat them as customers … that’s the language we use because I think that explains the role we play.”

But in interviews we conducted over the past six months, both platforms and publishers repeatedly used words like “partner” and “partnership” to describe their increasingly close relationship. While it’s unclear which side first pushed this more intimate vocabulary, it fits. The relationship between the two has evolved from one based on simple distribution to one built around product opportunities. One large publisher described the evolution this way: “Now it’s becoming, ‘how do we collaborate on new products? How do we do co-sale things together?’”

Accordingly, there’s been a notable increase in the frequency and type of communication between platforms and publishers as both sides formalize the management of these relationships. It was clear from our interviews with larger, well-resourced news organizations that their platform interactions happen across multiple departments, and generally more frequently than with smaller publishers who might only interface with a platform’s product support team. One larger publisher told us:

“Platforms used to primarily anchor their relationship with publishers around the distributing of content on their platforms. The platforms have gotten smart to the fact that several partners need the benefit of interfacing with multiple parts of their company. As a result, I’ve noticed that some of the big platform companies have worked to create more central, holistic management of touchpoints across their organizations.”

In interviews, we heard a growing list of terms among publishers that accompany these new relationships:

Overall, while the specifics (including the platforms interacted with, and the format and frequency of those interactions) varied from publisher to publisher, in our interviews many spoke of weekly and monthly calls and in-person meetings, as well as routine trainings around best practices or specific products. Apple News, for one, has increased in importance among publishers, and many larger outlets are in frequent contact with its newsroom. One publisher said:

“We’re on Slack with the Apple editors every day. We’re pitching stories. They know what’s coming from us. They know our budget. They tell us when they have opportunity for certain kinds of collections or curations and [ask] if we have anything that would fit that bill. We don’t contort ourselves, but certainly if there’s an opportunity [to be showcased on Apple News] we think about: does it make sense for us, editorially?”

The uneven power balance

This evolving publisher-platform partnership is unequal, however. Platforms wield more power over formats and data, and earn significantly more advertising dollars in aggregate than publishers, even as platform choices increasingly inform publishers’ editorial strategies, distribution strategies, and workflows. One larger publisher told us that when they meet with a platform’s business department to discuss direct monetization opportunities, these types of meetings can be “fraught,” because they directly involve revenue.

This publisher said, “Platforms come in and say, ‘Here’s what we’re launching. Here’s how it’s going to work. Here’s how you can participate.’ They never once asked, ‘How do you see this working for your businesses?’”

If news outlets were once cautiously optimistic about what their relationships with platforms might yield, that has now turned to seasoned skepticism. As one publisher told us, “Platforms are proactively getting in touch a bit more. They’re getting more active about scheduling meetings and check-ins. … There is more receptiveness towards getting more involved, though that doesn’t necessarily always mean a greater flow of information or answers to all questions that we ask.”

Publishers remain frustrated by the inconsistency and depth of audience insights and analytics provided to them by platforms. And even as platforms cede select additional data to publishers, including, for example, the change Facebook made in May allowing publishers to see whether video viewers are followers or non-followers and “audience retention by gender,” one platform told us that they “draw the line” on providing audience insights to publishers where “it’s competitive information for us.”

Platforms by and large say they are trying to find ways to accommodate publishers, but never at the expense of their own relationship with their users. One platform described a certain publishing product rollout, saying, “It was not really outreach to the news industry as much as it was trying to fix a user problem.”

How publishers use these platforms

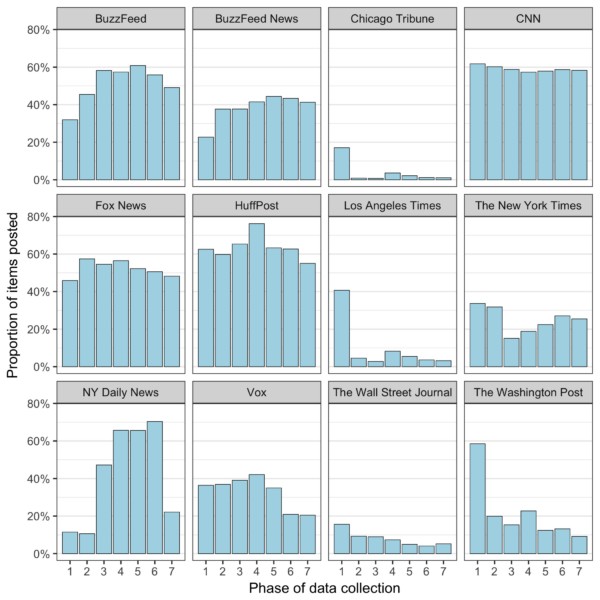

Our content analysis data shows that since early 2016 platforms have become central to where and how audiences find news content. While our interviews highlight various misgivings that publishers have about relinquishing control over the publishing process to tech companies, our data suggests that publishers continue to post their content to social platforms at unwavering rates.

In tracking the platform usage of 12 major publishers, the amount and frequency these news outlets posted to 14 platforms remained remarkably consistent over the 18 months of our analysis. The total number of items posted hovered around 22,000 during each of seven weeklong phases of study, accounting for an average of 1,800 items per publisher.

This rate of third-party publishing continues even as many news outlets are realizing they cannot win the scale-based game that seeking sustainable digital ad revenue requires. Currently, more than 70 percent of all US digital ad revenue goes to Google and Facebook. And these gains do not appear to have been shared: a recent study of the digital revenue composition of 21 large publishers revealed that earnings from Google and Facebook represented only five percent of the average total.

Platform Usage by the Numbers

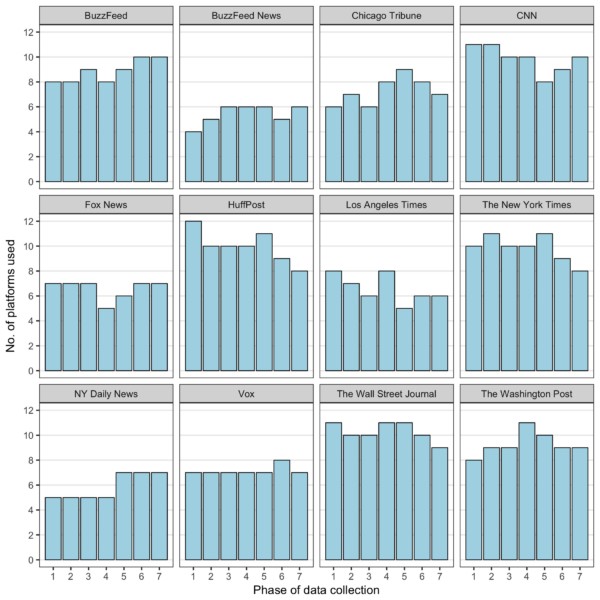

Chart 1 shows the number of different platforms used by publishers in our study during each of seven weeklong phases of analysis beginning in August 2016 and concluding in late March 2018. The platforms included in our study were Apple News, Facebook, Instagram, Instagram Stories, li.st (formerly The List App), LINE, LinkedIn, Messenger, Pinterest, Snapchat Discover, Snapchat Stories, Tumblr, Twitter, Vine, and YouTube.

Chart 1: The number of different platforms publishers used during each phase of data collection (August 2016–March 2018).

All publishers posted to multiple platforms during each week of analysis—with many frequently posting to 10 or more. BuzzFeed News’s use of four platforms during the earliest phase of analysis, in August 2016, was the lowest observed.

The highest number of different platforms employed in a week was 12 by HuffPost in November 2016 (Apple News, Facebook, Instagram, Instagram Stories, LINE, LinkedIn, Messenger, Pinterest, Snapchat Stories, Tumblr, Twitter, and YouTube). CNN and The Wall Street Journal both used as many as 11 platforms on different occasions, and The Wall Street Journal never used fewer than nine.

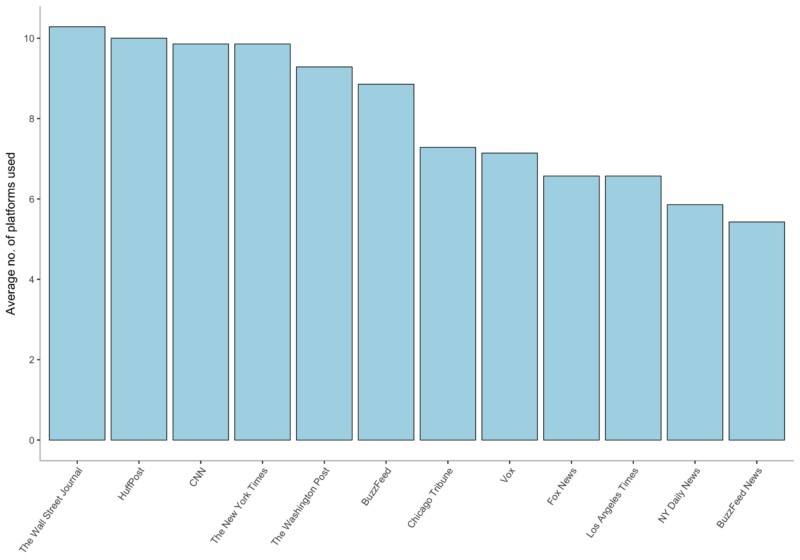

CNN, HuffPost, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal all used an average of 10 platforms per week, closely followed by BuzzFeed and The Washington Post with nine. The three local publishers—the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and New York Daily News—were at the lower end of the scale, typically using six to seven platforms per week.

Chart 2: The average number of platforms used by each publisher per phase across all seven phases of data collection (August 2016–March 2018).

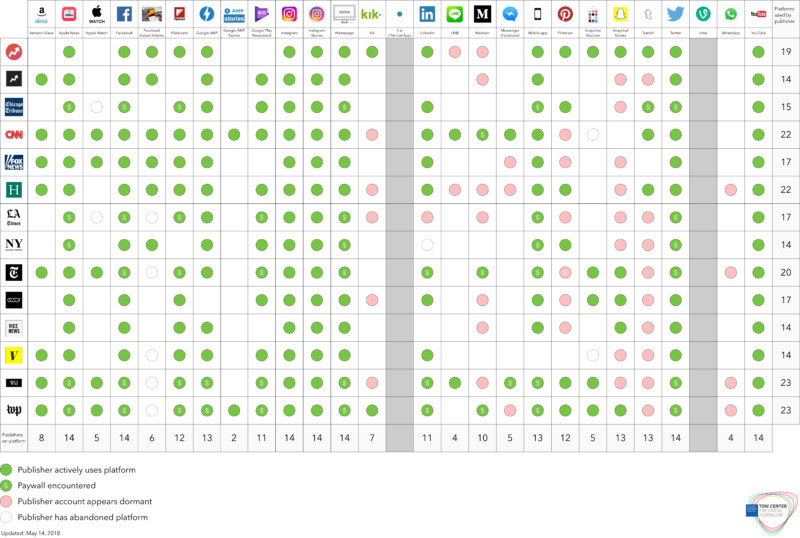

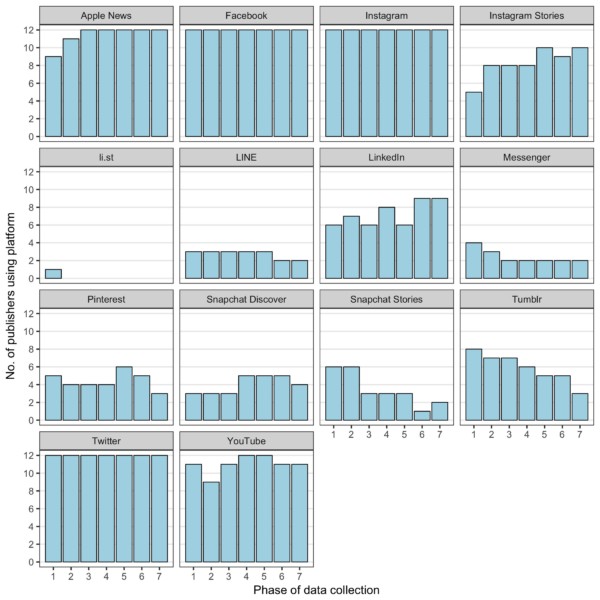

Assessing platform use highlights the indispensability of Apple News, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to these 12 publishers. YouTube and Instagram Stories were not far behind, but most others were used far more selectively.

Chart 3: The number of publishers using each platform during each phase of data collection (August 2016–March 2018).

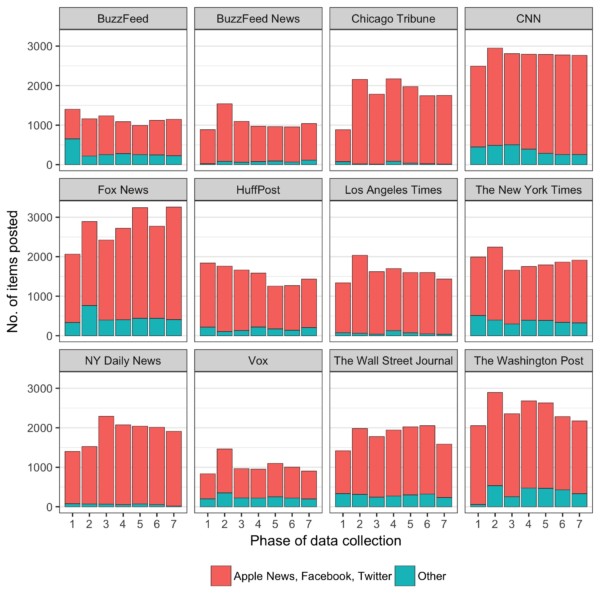

Apple News, Twitter, and Facebook dominated—particularly at the regional metros. For every publisher, the amount of content posted to Apple News, Twitter, and Facebook dwarfed that distributed to the 11 other platforms we tracked.

This was particularly pronounced at the three regional metros—the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and New York Daily News. By the time of our final analysis, in March 2018, just one percent of posts made by these three regional publishers went outside of Apple News, Twitter, and Facebook.

This is in stark contrast to some of the other publishers. For example, around 20 percent of posts made by two of the digital natives—Vox (22 percent) and BuzzFeed (20 percent)—went to platforms outside of Apple News, Twitter, and Facebook. These were closely followed by the three bigger, more-resourced publishers—The New York Times (17 percent), The Wall Street Journal (15 percent), and The Washington Post (15 percent)—all of which continued to try and reach their audiences in different places with posts across a wider variety of platforms.

Chart 4: The proportion of posts made to Apple News, Facebook, and Twitter (red) versus the other 11 platforms studied (August 2016–March 2018).

Informing editorial and newsroom strategy

Platform audience insights and priorities both factored heavily into the types of stories commissioned by publishers we spoke to, and also the formats through which those publishers chose to tell stories. Anything from, for example, platform data provided about average video view time to Facebook’s decision to promote Live video in its News Feed, informed publishers’ editorial choices. One publisher noted that audiences on Facebook would watch videos longer if they opened with a climax that traditionally comes later in the video, so the publisher began to produce videos that way.

Platforms’ quickly changing priorities, however, make formulating long-term strategy for publishers nearly impossible. The Tow Center has been tracking decisions by platforms and platform-related events that affect publishers, from policy and product updates to monetization opportunities, and we’ve observed more than 600 developments in the course of our research that have accumulated and, in some cases, resulted in costly outcomes for publishers.

Platform Changes Informing Newsroom Strategy

The power of platform decisions to influence publishers’ distributed strategies can manifest in a variety of ways.

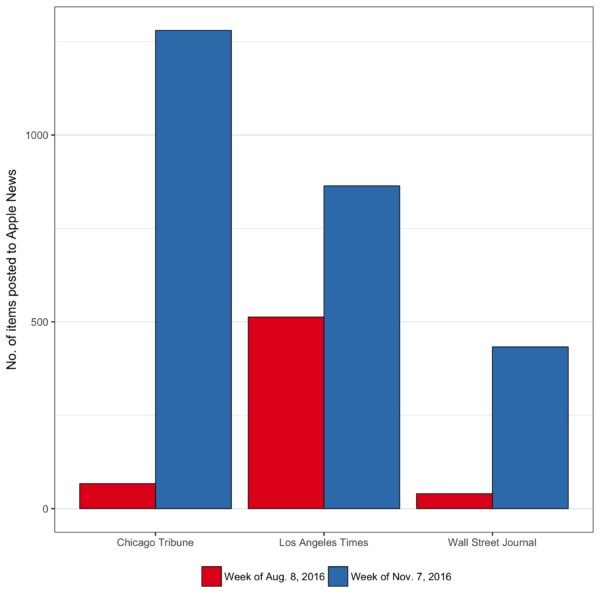

When Apple News introduced a paywall facility in September 2016, the number of articles posted to the platform by subscription-based publishers such as the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and The Wall Street Journal shot up. Apple News has a massive potential audience and the introduction of a paywall offered a new source of potential income for publishers.

Chart 5: The number of articles posted to Apple News in weeklong periods before and after the paywall facility was introduced.

Platform changes also influenced publishers’ distribution strategies in other, more subtle ways.

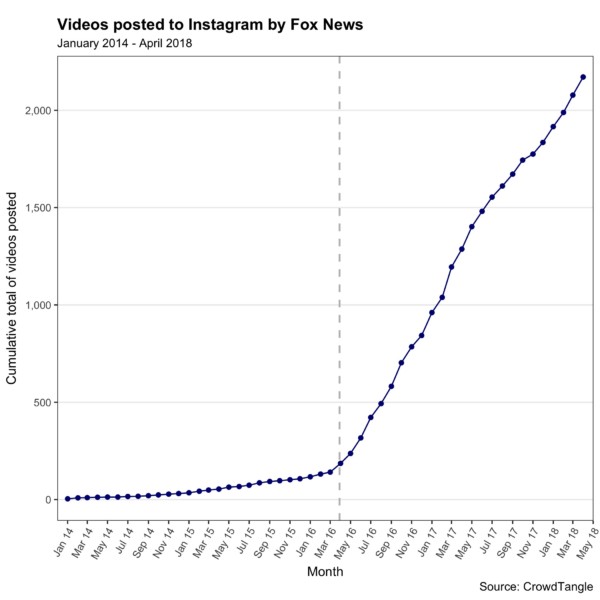

For example, when Instagram rolled out an update increasing the maximum length of videos from 15 to 60 seconds, the number of videos published to the platform by Fox News jumped substantially and near immediately.

Unlike the Apple News paywall, or publishers opting in to new products like Facebook Instant Articles, this uptick in usage was not about exploring potential sources of revenue—as Instagram does not offer any kind of revenue share. An increase in Instagram posts was purely a brand play.

Chart 6: Videos posted to Instagram by Fox News (January 2014–May 2018).

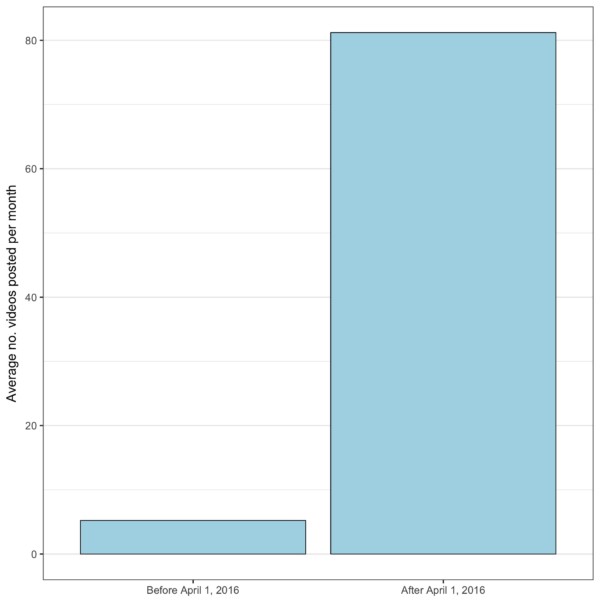

In the 27 months spanning January 2014 to March 2016, Fox News posted an average of five videos to Instagram per month. In the 24 months after the maximum video length increased to 60 seconds, beginning in April 2016 and running through March 2018, the monthly average increased 1,520 percent to 81 per month.

The 156 videos posted in March 2017 alone—an average of five per day—equates to 15 more than were posted in the 27 months prior to the introduction of one-minute videos.

Chart 7: The average number of videos posted to Instagram by Fox News before and after Instagram increased the maximum video length from 15 seconds to one minute.

Audio is emerging as the newest example of the continuing power of platform products and priorities to influence editorial strategy. With the availability of Amazon’s Echo and Google’s Google Home Assistant—and with Facebook soon introducing its own smart speaker—publishers are beginning to rethink content creation based on new formats and audience behavior on smart speaker platforms. Just one month after the May 2017 launch of Amazon’s new video-enabled smart speaker, the Echo Show, CNN, Time Inc, and Bloomberg already had content in the works.

Designing news content that fits the home speaker platform is not straightforward, though. In one interview we conducted, an audio publisher noted the challenge of creating output for smart devices that live in intimate spaces, like the bedroom:

“The adoption in smart speakers is really bringing radios back to those counters and bedside tables and everywhere else in a way that is terrifically promising. Where user behavior goes next is a big open question. Are people going to really learn to talk to these speakers? Will they become trusted companions? … It’s something where we’re investing a lot of time and energy right now because we do believe there’s a lot of audio opportunity and content opportunity on those platforms.”

Publisher pushback

Despite a trend that sees publishers tailoring news outputs to platform products, which we observed beginning in our 2016 interviews, in some cases publishers are becoming more cautious about how and when they adjust editorial strategy to fit platform requirements.

One said, “I think the platforms started influencing content creation because they rewarded a certain type of content. That made everyone want to maximize that and create stuff the same way. Over time, though, once publishers realized that this contract with the platforms wasn’t going to pay off the way they thought it would, it became a little bit of ‘back to the basics.’”

A digital-native publisher reflected, “Platforms don’t always reward the best behavior. So you can end up in a rabbit hole where you look at your product in the rear-view mirror and think, ‘Is that what I intended to create?’” Even these publishers that once thrived by conforming almost entirely to platform priorities are increasingly asking, “How do we match up what we consider important journalism with extreme audience optimization … those things don’t always click.”

Still, ad-supported digital-native and platform-native publishers remain the most inclined to be directly responsive to platform interpretations of what users want. One said, “Publishers will talk as if Mark Zuckerberg is literally the Wizard of Oz, the man behind the curtain, [who is] going to suddenly point all of the audience at a thing, or away from [it].” The publisher added: “We are very concerned with what the audience is telling us they want more of. Not every publisher is that type. For some publishers it’s all about writing for the right audience. Our interests are in talking to bigger audiences. So if you’re going to do that [as a publisher], then you need to pay attention to what people want.”

One question remains central to this struggle: to what extent are platforms reflecting user desires versus shaping user behavior? One local publisher reflected on the day-to-day nature of this tension: “There are, I believe rightly so, conversations we have internally about if we’re doing a story because we think it’s going to do well on social. Do we think this is going to be a win on Facebook? Is that the reason we’re posting this story?”

Facebook dominance and discontent

Throughout our research, Facebook has remained for the majority of publishers we interviewed the top platform for reaching and engaging audiences, and for subsequent monetization opportunities. It continues to dominate every part of the digital publishing value chain. Its publisher products are not only for distribution and audience engagement (e.g., Instant Articles), but also for production (e.g., Live), and for multiple forms of monetization (e.g., the Audience Network, which allows publishers to insert ads from Facebook’s ad network into, for example, their Instant Articles as the platform acts as a sort of middleman between publishers and brands).

Facebook, therefore, has had more touchpoints with the publishing industry than other platform companies. Because of this prominence, publishers expressed more frustration toward Facebook than any other platform—and those frustrations are mounting. As one publisher put it, “The other social platforms, like a Twitter or a Snapchat or a Reddit, I think we don’t get as angry with them because our business isn’t affected by them as much.”

While Google has collected more user data and captured more digital ad revenue than Facebook, there are crucial factors which differentiate the two platforms with regard to publisher usage—and which explain publishers’ most common reactions to Facebook. The Facebook user experience is designed to keep audiences on the platform, displacing control over audiences and monetization from publishers. Google’s search and news products, on the other hand, connect readers to publishers’ content across the open web by pointing traffic at publishers’ own sites and article pages.

Though Google’s PageRank is no longer public, publishers generally know the types of inputs to the algorithm and how to optimize their digital content for Google search. Facebook’s News Feed algorithm, by contrast, is mostly a black box. Publishers hear when the News Feed is, for instance, prioritizing video one month and posts from friends and family another. But the only way for a publisher to ensure prominence in users’ feeds is to pay for placement via promoted posts.

Our interviews with publishers, therefore, indicate two major areas of discontent with Facebook. First, publishers are frustrated by frequent changes regarding the platform’s products and how they are prioritized and monetized—since this has a direct impact on newsroom workflow and revenue outlook. Because Facebook is a platform built around fostering and monetizing on-site user engagement, it cares deeply about the functionality and relevance of its product to its users. This central concern with the user-product relationship—and the product-advertiser relationship—means that Facebook engages in frequent product updates and new product rollouts to test ways to keep users on the site and help advertisers locate new customers.

One publisher nicely summarized the sentiments of many others around the volume of changes: “Now I think everyone is kind of getting frustrated. We’re not going to change our workflow entirely because of something Facebook is changing.” Another publisher, commenting on the specific product changes which publishers have had to navigate, said, “Pivot to live, pivot to video, pivot to groups. You know, at some point, people are going to just get a bit tired.”

Additionally, publishers struggle with what they perceive to be opacity and capriciousness around the News Feed curation algorithm. In our earliest interviews, publishers wrestled with just how much to allow Facebook’s algorithm—a reflection of its priorities when surfacing popular and engaging content—and audience insights to factor into editorial strategies. Lighter content, or “soft news,” is easier to like, share, or react to, and generally performs better on a platform like Facebook. As one publisher put it, “A major news brand can’t say, ‘Our audience doesn’t care about Haiti right now unless Trump calls it a shithole’ … You still have to put it [on Facebook].”

Even in more recent interviews, there has continued to emerge a language of helplessness around the News Feed algorithm. Though Facebook has signaled increasing openness to collaboration and feedback on other parts of its product, the News Feed remains a closely guarded component of the platform. One publisher described the effect of shifting News Feed priorities as “riding these traffic waves and hoping that the height of the wave this month is sufficient to keep the lights on.” And because the News Feed algorithm is not designed to build loyalty to a single publisher, but to tailor individualized streams of content and advertising for the Facebook user, publishers described reluctantly having to “pay to play,” meaning pay to promote posts in order to ensure that their content reaches a News Feed audience.

A month after Facebook made yet another significant change to its News Feed, in January 2018 to de-prioritize news in favor of more “meaningful interactions with family and friends”—one that particularly threatened the livelihood of some smaller publishers and forced at least one to shut down—Facebook’s publisher-wrangler-in-chief Campbell Brown shrugged at disgruntled newsrooms, saying, “If someone feels that being on Facebook is not good for your business, you shouldn’t be on Facebook.”

Despite rising disillusionment, many publishers continue to maintain cordial relationships because they do not want to miss out on new product rollouts or other opportunities. One national publisher described wanting “to be in Facebook’s good graces.” Another local publisher was more resigned, saying, “We feel like we can’t afford to be critical, because God forbid there is some sort of resource or benefit that we need to be considered for down the road.”

A handful of publishers, however, have come to Facebook’s defense. Their view is that Facebook is too often the scapegoat for all of news publishers’ revenue and audience problems, and that news outlets expect more than they should from platforms—more than they might give if the tables were turned. In our initial interviews in 2016, one national publisher said:

“I know there’s a desire to put them in the good or bad bucket, but I feel like every time we have a conversation about Facebook there’s this need to ascribe intent. Do they have good intentions or bad intentions? But I just don’t think it’s either or. I think they are very focused on making sure they have an engaged audience that continues to grow and invest in Facebook, and they need publishers to continue to build out that ecosystem. They’re definitely not going to put the publisher needs and desires first. They’re putting the Facebook audience needs and desires first.”

In recent interviews, a local publisher said of frustrations with Facebook’s news partnerships team, “I think people sometimes forget that those who can make things happen are not necessarily the people we’re talking to. It’s people above them who have to make decisions that fit into Facebook’s overall strategy, and I doubt they’re going to pick something that hurts them to help us.”

However, when it comes to Facebook’s dominance in publisher complaints, it could also be that publishers have short memories. After all, it was Google’s First Click Free policy that initially upset publishers looking to reach audiences online. First Click Free raised a generation of internet users on free news, and conditioned users’ willingness to pay down to almost zero. This rock-bottom readiness to pay played a role in the evolution of digital publishers’ business models toward the focus on advertising and social scale; it is also one of the major challenges publishers face in pivoting to reader revenue through subscriptions and donations. Though Google has recently abandoned First Click Free, and now allows publishers to choose how many articles to allow Google users to read before they hit a publisher’s paywall, it remains to be seen how the partnership between publishers and Google will take shape in the wake of Facebook’s PR problems.

Local News and the Diverging Experiences of Smaller Publishers

Local news publishers in particular have been hit hard by the loss of print advertising revenue, and in our initial interviews in early 2016 felt de-prioritized by platforms and cut off from these potential new monetization opportunities. One local publisher told us then that platforms were taking a “class-based approach.” Small publishers felt left out of early platform products like Instant Articles and Snapchat Discover, and, in many cases, still don’t have the resources to experiment or participate with new products like Facebook Watch, a section of the platform for video on demand shows that launched in August 2017.

One local publisher asked, “In newsrooms where your workforce is shrinking basically every year, is it worth it to spend time on an Instagram Story?” Another local publisher said, “Apple News is not picking up the phone and saying, ‘Hey, would you like to be a partner with us?’ So being a little fish in a big pond, sometimes we can get skipped over. Sometimes we have to go the extra mile to get in on the newest thing.” Yet another local news publisher said, “We still don’t have the staff in place to do the kind of journalism that people are looking for on these platforms now … we don’t have the people to build the kind of content that these social media platforms want to bubble up.”

Exclusion from platform opportunities

Platforms consistently privilege larger publishers, who generally hear about monetization opportunities first and have more access to platform partners. As platforms expand their offerings, publishers who don’t fall into this group can still ingratiate themselves with new platform initiatives if they align with a platform’s product development goals at any given moment (for example, a local publisher with a paywall might be asked to join a test of Facebook’s subscription product, but is unlikely to see outreach from Twitter to create a show for the platform).

In platforms’ initial rollout of publisher products, audio publishers were also shut out. In our early interviews one audio publisher described creating a workaround to the Facebook video player to get audio prioritized by Facebook’s News Feed algorithm. Another audio publisher said, “The main platforms are all so concerned with video and visuals and text, it’s been hard to convince them otherwise.”

One factor explaining the disparity in publisher experiences vis-à-vis platforms is larger publishers’ ability to manage more sophisticated relationships, and the return on investment that platforms see in those publishers. As one national publisher put it, “Some of the bigger publishers have always had good business development teams and abilities to manage that ongoing relationship, because it’s not exactly editorial. It’s a combination of editorial and business value that you’re constantly exchanging with these platforms.”

A local publisher described “clawing and scratching and screaming” to get platform attention while a large publisher acknowledged that due to its size and audience “[platforms] come to us with more opportunities and therefore we take advantage of those opportunities … it’s a virtuous circle.”

Disparity in platform usage

Our data shows that the larger, better-resourced publishers consistently posted more content to a greater range of platforms. The smaller outlets were almost entirely focused on Apple News, Facebook, and Twitter. This was particularly pronounced at the three regional metros, the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and New York Daily News. By the time of our final analysis, in March 2018, just one percent of posts made by these three regional publishers went outside of Apple News, Twitter, and Facebook.

Volume of Content/Diversity of Platforms Used by Publisher Size

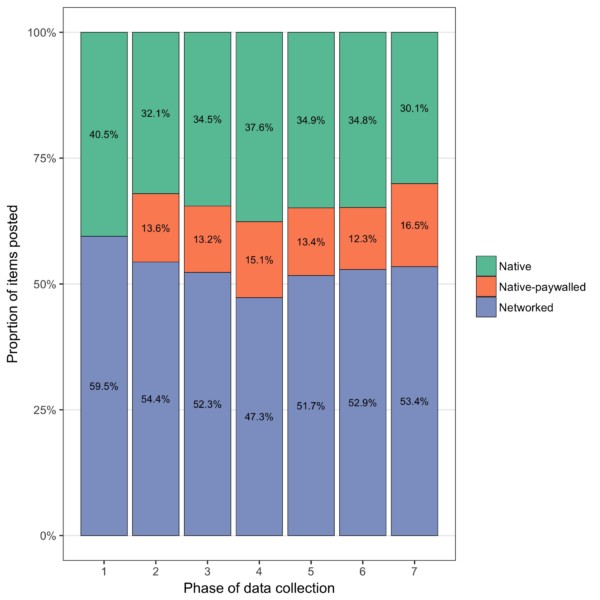

Assessing the distribution of posts on a publisher-by-publisher basis, it is useful to compare the lesser-resourced newsrooms with their larger counterparts.

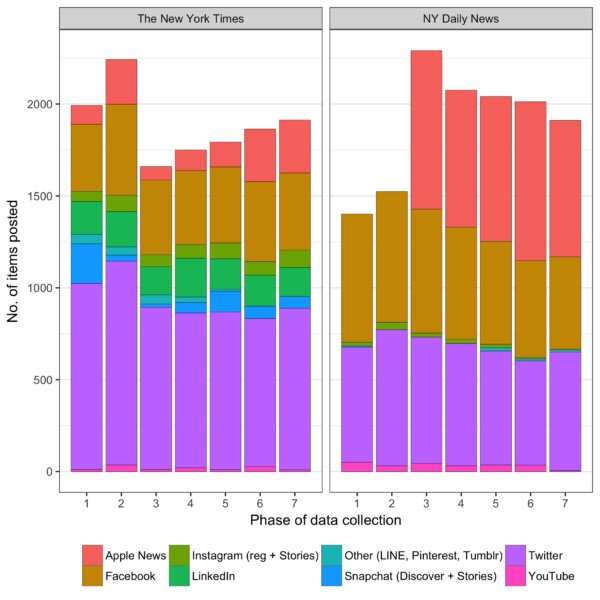

Take, for example, the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and New York Daily News—all dominated by three colors in Chart 8 representing Apple News, Facebook, and Twitter—with the multicolored charts representing the likes of CNN, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post.

Chart 8: Total number of posts made by each publisher during each phase of data collection, separated by platform.

If distribution is about meeting audiences where they already are, then data shows how bigger publishers have the ability to pump out more content to a wider variety of destinations (thereby increasing the chances of meeting more people in more places), while the lesser-resourced ones are forced to prioritize certain platforms—Apple News, Facebook, and Twitter, in particular—while making rarer, more sporadic posts to other platforms when time or resources permit.

Comparing the two New York-based titles, for example, there is stark contrast between the rainbow of colors in The Times’s distribution chart and the almost tritone equivalent produced for the Daily News.

Chart 9: Comparing the destinations of platform posts made by The New York Times and New York Daily News.

Concern for the health of local news and the promise of platform help

Platforms are, however, increasingly turning some of their attention toward the needs of small and local publishers. Since the 2016 presidential election, as questions around an informed public and democracy came into the spotlight, some platforms have been more inclusive of small and local newsrooms in product rollouts, and have launched initiatives to support local news.

The 300-million-dollar Google News Initiative, which houses news-related efforts like partnerships with nonprofit organizations that represent local media, and Facebook’s Local News Subscriptions Accelerator, which promises to help a dozen or so news organizations gain digital subscribers, both launched in the first months of 2018.

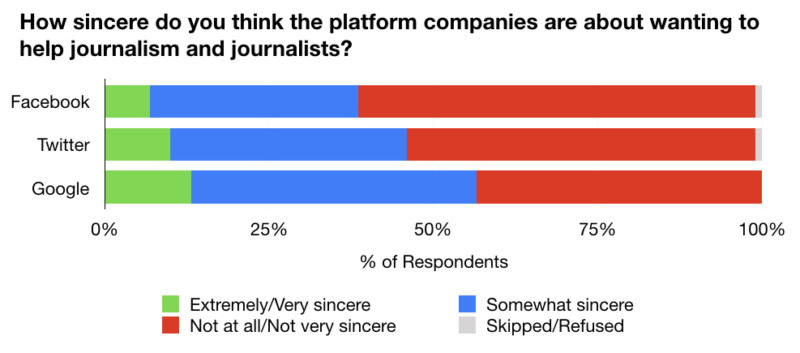

However, our data and survey findings suggest that publishers remain wary. According to the API/NORC survey, most of the skepticism (by journalists working at local and national news organizations) is reserved for Facebook—with only seven percent of the respondents saying they think the company is “extremely sincere” or “very sincere” about wanting to help journalism and journalists. Still, neither Twitter nor Google had particularly flattering numbers, with 10 percent of respondents believing the same of Twitter and 13 percent of Google.

Publishers we interviewed who participated in one of Facebook’s recent local news initiatives found their involvement to be frustrating and ineffective. One participating publisher said, “There’s all this PR speak about the importance of local journalism, but when it comes down to it [the platforms’] actions do not align with that.” Another local publisher said, “Facebook always puts out a fat mic: ‘we’re here for you, we’re here for journalists.’ But ultimately getting in touch with them is very difficult. Getting a straight answer out of them is difficult.”

Furthermore, although both Google and Facebook have made public statements about prioritizing local news, some local publishers noted that the platforms’ algorithms will often surface national or aggregated takes on stories they break. One local publisher said, “That is something that completely chaps my ass routinely—when I see people [locally] sharing national versions of stories that were broken by my news organization. It just makes me lose my mind.”

In late January 2018, Facebook also promised local newsrooms that a change to its News Feed algorithm would prioritize local journalism. Mark Zuckerberg posted on his personal Facebook page: “Today our next update is to promote news from local sources. People consistently tell us they want to see more local news on Facebook. Local news helps us understand the issues that matter in our communities and affect our lives. Research suggests that reading local news is directly correlated with civic engagement. People who know what’s happening around them are more likely to get involved and help make a difference.”

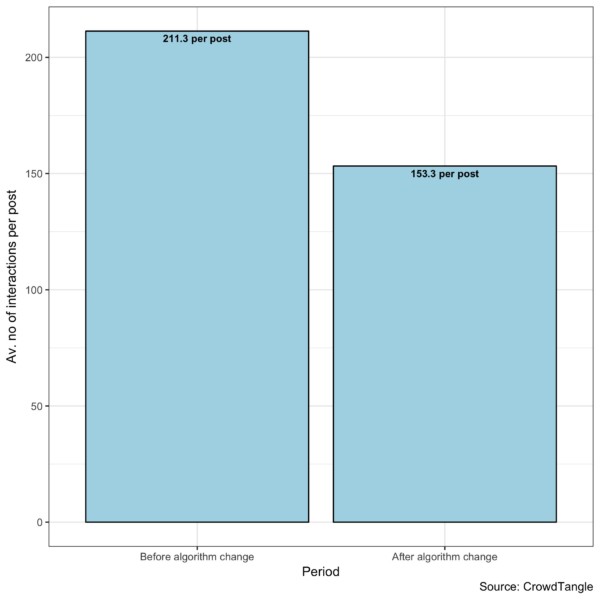

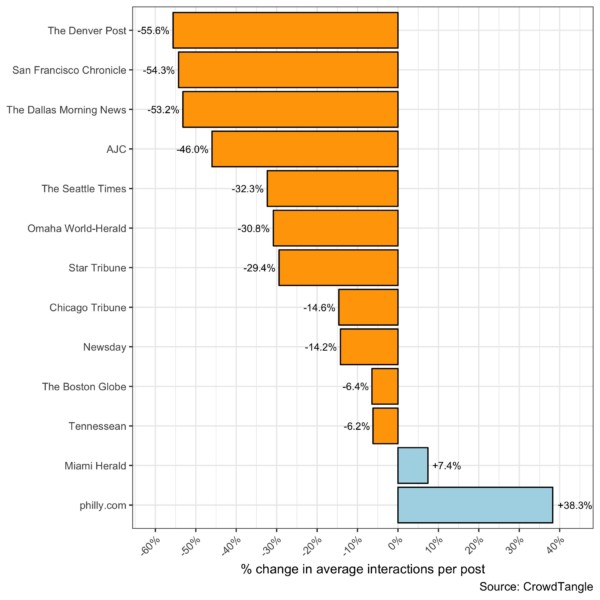

As Tow researcher and report author Pete Brown wrote for CJR in April 2018, based on analysis of 13 regional metros both before and after the algorithm change, Facebook “is already missing the mark on one of its central goals for 2018: giving local news a shot in the arm.”

Our data indicates that Facebook interactions with local journalism posts are down by as much as 56 percent compared to the two years prior, as 11 out of 13 regional metros averaged fewer interactions per post in the nine weeks following the pro-local algorithm change than in the two years before.

Local News and the Facebook Algorithm Change

To assess the impact of Facebook’s January 29, 2018, algorithm change to promote “meaningful interactions” with local news, we evaluated 13 regional outlets—chosen because they participate in Facebook’s Local News Subscriptions Accelerator. Data was collected from CrowdTangle (the monitoring tool now owned by Facebook) on Tuesday, April 3, 2018. It covers the period between January 1, 2016, and April 1, 2018. Interactions were calculated by summing reactions (likes, hahas, etc.), shares, and comments for each post. (This research does not assess the success of the Local News Accelerator, which Facebook announced in February to help news organizations gain subscriptions.)

Chart 10: Average interactions with Facebook posts before and after the pro-local news algorithm change (January 1, 2016–January 28, 2018, versus January 29–April 1, 2018).

Chart 11: Change in average interactions with Facebook posts before and after the pro-local news algorithm change (January 1, 2016–January 28, 2018, versus January 29, 2018–April 1, 2018).

Inability to Monetize On-Platform

When we asked publishers in our interviews about monetization on platforms, the answers we heard varied significantly. Some said monetization on YouTube is good. Others said it’s awful. Some said Apple is reliable for making money and others said it’s nonexistent within their revenue strategy. One publisher called Snapchat a “suboptimal monetization platform” and another said it’s “just horrible,” while a third said it’s become a worthwhile partnership. While most publishers whom we spoke to were happy with Twitter, one publisher called it “a garbage fire.”

What is becoming clear is that attempting to translate the advertising-driven business model of news publishing from print to digital by posting high volumes of content to social platforms and adopting platform-native products has not been lucrative for publishers.

Failed products

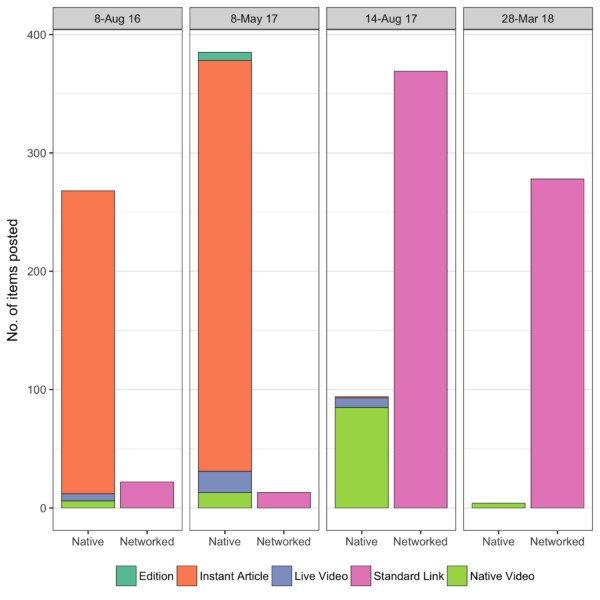

The data for financial success around Facebook-specific products, especially, tell a story of limited outcome. Take, for example, Instant Articles. As Pete Brown wrote for CJR in February 2018:

“When launching the product in May 2015, Facebook presented its new initiative as a commitment to helping publishers monetize journalism distributed via its platform. Instant Articles, it was claimed, would solve the problem of sluggish mobile websites. While publishers would have to host their articles on Facebook’s servers and post natively to the platform, they would supposedly reap rewards—in terms of scale, engagement, and revenue—from being able to serve mobile content that loaded at lightning speeds via Facebook’s app.”

Michael Reckhow, then-product manager for Instant Articles, introduced the product this way: “We designed Instant Articles to give publishers control over their stories, brand experience, and monetization opportunities. Publishers can sell ads in their articles and keep the revenue, or they can choose to use Facebook’s Audience Network to monetize unsold inventory. Publishers will also have the ability to track data and traffic through comScore and other analytics tools.”

When Instant Articles launched, many high-profile publishers jumped at the opportunity to try it. In September 2015, The Washington Post announced it would “send 100% of its stories to Facebook so that all Washington Post content can be formatted as Instant Articles, giving readers a lightning-fast user experience for reading, sharing and commenting within the Facebook iOS app.”

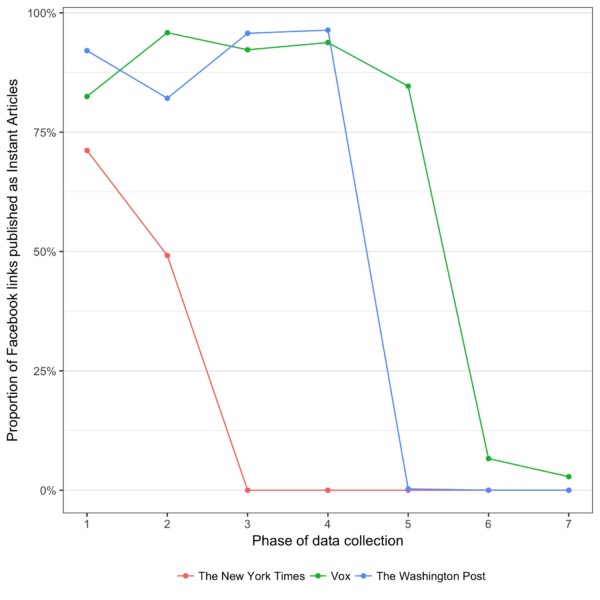

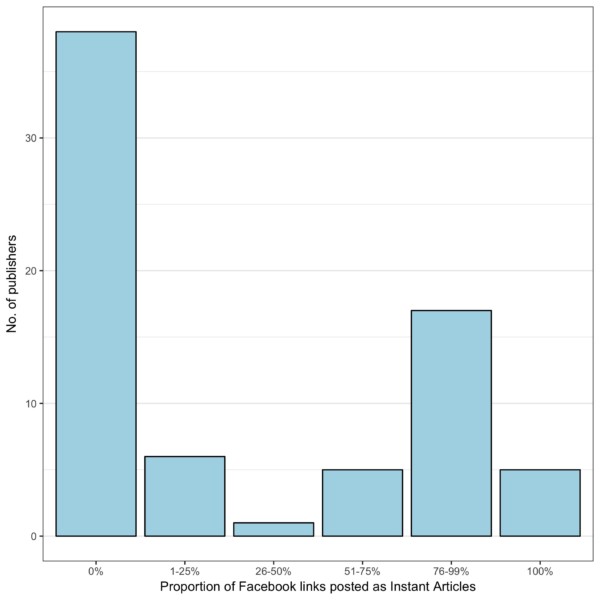

But a little more than two years later, in early 2018, over half of Facebook’s launch partners for Instant Articles were not using the format. Of 72 publishers that Facebook identified as original partners in May and October 2015, our analysis of 2,308 links posted to their Facebook pages on January 17, 2018, found that 38 publications did not post a single Instant Article.

Abandonment of Instant Articles

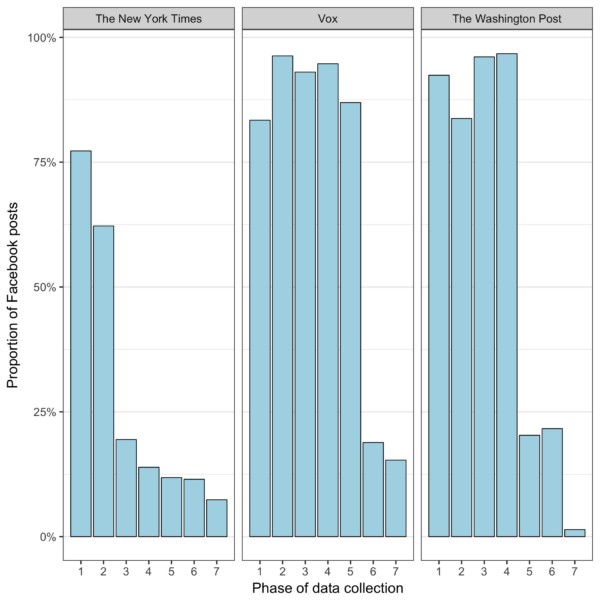

Chart 12: The proportion of Facebook links published as Instant Articles by three news outlets that have now abandoned the product (August 2016–March 2018).

Chart 13: Use of Instant Articles by 72 early partner news outlets, as of January 17, 2018.

The decision to shun Instant Articles means that considerably more links direct traffic back to publishers’ websites than remain native to Facebook. Of the 2,308 links analyzed, 1,491 (around two-thirds) went to a publisher’s homepage, leaving 817 as Instant Articles.

For CJR, Brown concluded: “Instant Articles has been criticized for underwhelming monetization, limited user data, and underwhelming options for subscription-based outlets.” Even so, he noted that it’s difficult to argue that Instant Articles is an altogether failing product when Facebook can still point to growth and huge usage numbers. “Last June, the company boasted that it had ‘10,000 publishers around the world using Instant Articles, growing over 25 percent in the last six months alone.’ But, with the high-profile publishers moving out of Instant, is this another example of Facebook prioritizing quantity over quality?” Brown asked.

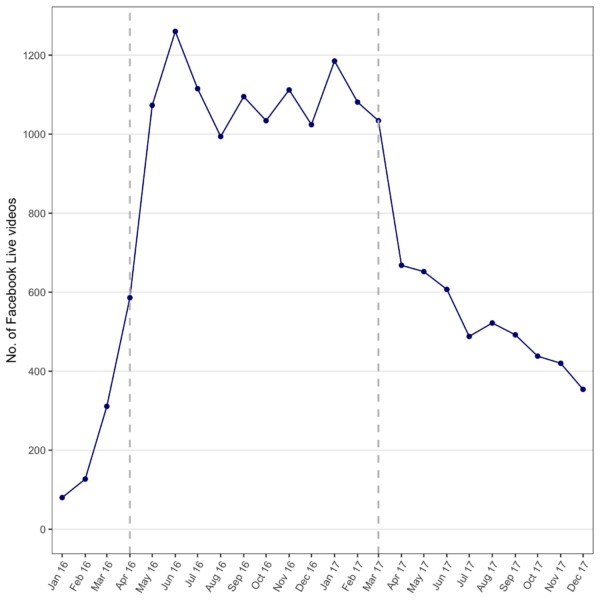

In another case, our data shows that publishers seemed to have also abandoned Facebook Live once financial incentives from Facebook to use it expired. According to The Wall Street Journal, Facebook reportedly began paying select publishers and personalities in March 2016 to produce Live videos for its platform. A select few included BuzzFeed, The New York Times, CNN, HuffPost, and Vox Media. (The Wall Street Journal estimated that these top outlets each received anywhere between 1.2 and 3.1 million dollars in compensation.) At the time, Facebook also calibrated its News Feed to prioritize Live videos over other types of content.

As Brown published on CJR in February 2018, “A year later, Live swiftly fell out of favor and ‘longer, premium video content’ became the new priority. Watch, the platform’s video on demand service, has become Facebook’s video product du jour.”

As such, the number of Facebook Live videos produced by paid partners more than halved by the end of 2017 our data suggests—and in one case fell by as much as 94 percent—once guaranteed payments ended and Facebook de-prioritized the product.

Abandonment of Facebook Live Once Financial Incentives Ended

Our data analysis shows that of the 17 brands paid by Facebook to make live videos for the platform, the number published from April to December 2017 fell by an average of 51 percent when compared to the 12-month period from April 2016 to March 2017.

Chart 14: The number of Facebook Live videos posted by 17 paid brands during 2016 and 2017 (n=17,752).

Even with minimum guarantees in place, the terms around payment could change suddenly. As one large publisher detailed to us in an interview, in their case (publishers negotiated specific terms), first they received a monthly fee if they produced a set number of Live videos. The platform was, as this publisher put it, “paying to fill the pipes.” But when Facebook decided to focus on mid-roll ads placed against longer videos (meaning advertisement breaks that occur in the midst of viewing), the arrangement changed to mean that the publisher earned ad revenue only when it exceeded the monthly guarantee from Facebook—which did happen. So when the monthly guarantees stopped, the publisher assumed they’d continue to earn at similar rates even against mid-roll ads alone. Instead, they saw a dramatic decline in revenue they said they were not prepared for.

Still, no decrease in volume of content posted

Yet for all the turmoil and uncertainty in publishers’ relationships with tech platforms, those in our study have continued to populate third-party platforms with substantial amounts of content.

Volume of Content Posted

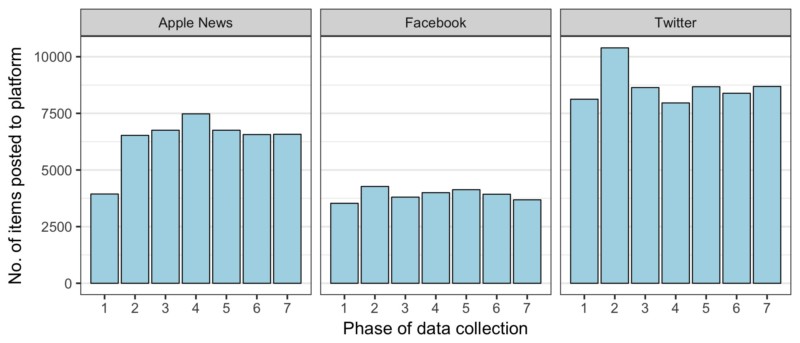

Following an unsurprising spike during the week of the US election (week beginning November 7, 2016), when a combined total of almost 25,000 items were posted, the number of posts pumped out to platforms remained remarkably consistent. The 12 publishers in our study typically posted a combined total of about 22,000 items per week—an average of 1,800 each—during each phase of data collection.

The consistency and sheer volume of content being posted to platforms highlights these publishers’ ongoing commitment to meeting their audience where it is—even though it’s on somebody else’s turf.

Chart 15: Aggregated number of posts recorded during each phase of data collection, separated by platform (August 2016–March 2018).

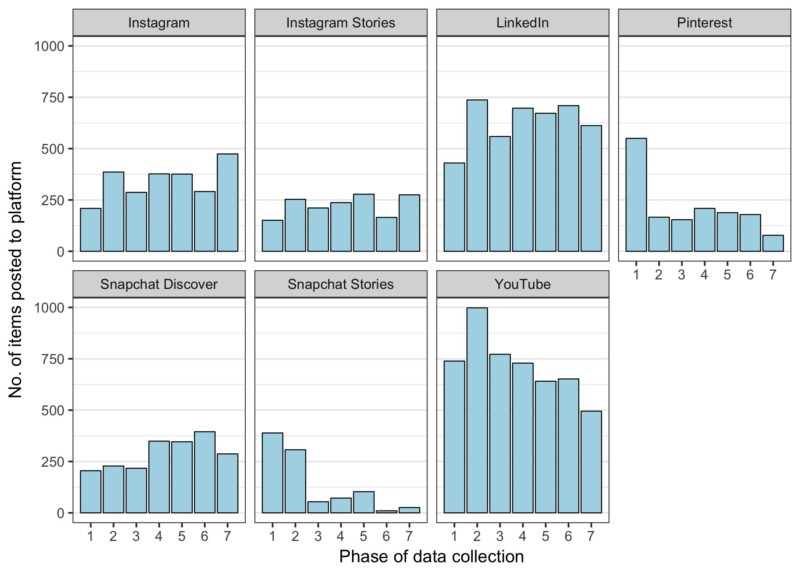

To evaluate how much content was published to each platform over our analysis, the 14 platforms in our study are best understood if they are broken down into three categories:

- High volume: Apple News, Facebook, and Twitter

- Medium volume: Instagram, Instagram Stories, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Snapchat Discover, Snapchat Stories, and YouTube

- Lower volume: li.st (formerly The List App, now defunct), LINE, Messenger, and Tumblr

Chart 16a: Total number of posts made to high-volume platforms during each phase of data collection (August 2016–March 2018).

Chart 16b: Total number of posts made to medium-volume platforms during each phase of data collection (August 2016–March 2018).

Chart 16c: Total number of posts made to lower-volume platforms during each phase of data collection (August 2016–March 2018).

A retreat from platform-native content

However, accessing the volume of content posted to platforms in isolation only tells part of the story. Our data also demonstrates how publishers attempted to wrestle back a degree of control from platforms by both reducing the amount of “free” content “given away” in the form of platform-native content and increasing the proportion of content placed behind platform-provided paywalls.

Networked versus Native Content by Publisher

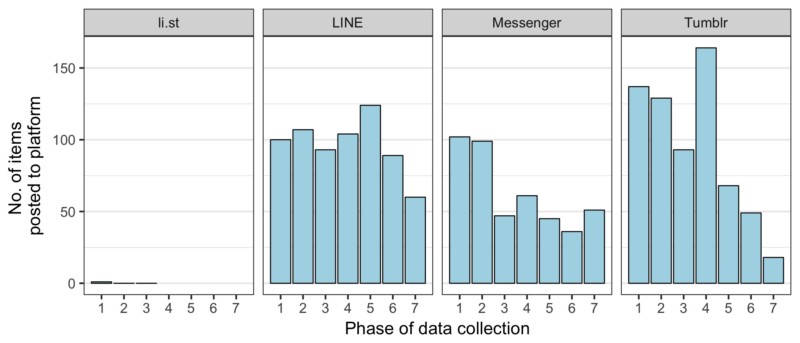

In our study we differentiated between three types of content:

- Networked—Posts made to platforms whose primary purpose is to drive audiences back to a publisher’s website (e.g., Twitter, Pinterest, LinkedIn, and Facebook links that are not Instant Articles).

- Native—Posts that were hosted natively on third-party platforms and could be viewed for free without a subscription (e.g., Instagram, Facebook Instant Articles, native Facebook videos, paywall-free Apple News channels, and Snapchat). This is content that publishers are sometimes said to have “given away” to platforms.

- Native paywalled—Posts made to third-party platforms that could only be viewed with a subscription (e.g., paywalled channels on Apple News).

The proportion of the content “given away” in the form of platform-native posts reached its lowest point in the March 2018 analysis, when it was recorded at 30 percent—down 25 percent from the level observed in August 2016.

Broadly speaking, as of the final phase of analysis, 70 percent of content was either (a) intended to drive traffic back to publishers’ websites or (b) required readers to pay to view paywalled content on a third-party platform.

Chart 17: The overall proportion of native, networked, and native-paywalled posts during each phase of data collection (August 2016–March 2018).

Chart 18: A breakdown of native, networked, and native-paywalled posts by each publisher during each phase of data collection (August 2016–March 2018).

Zooming in on the proportion of native (“free”/un-paywalled) content “given away” to platforms (Chart 19), a range of approaches come into focus.

- CNN’s approach to native content remained remarkably steady, settling on a strategy of posting around 60 percent of content in platform-native form. Similarly, HuffPost, a digital native, consistently made over half of its posts available in platform-native form.

- At the other end of the scale, the Chicago Tribune and Los Angeles Times remained steadfast in their refusal to give much away as native content, particularly once Apple News introduced its paywall. Another of the subscription-based outlets, The Wall Street Journal, frequently posted to a wide range of platforms, but typically made less than 10 percent of posts available in free, platform-native form.

- The New York Times flip-flopped to some extent, initially curbing its use of products such as Facebook Instant Articles and Facebook Live, but later embracing other native platform products such as Snapchat Discover, Instagram Stories, and increasing the number of articles posted to Apple News.

- Vox reeled-in the amount of platform-native content it posted by around half (largely due to its abandonment of Facebook Instant Articles). But by far the biggest change of heart came from The Washington Post. In the earliest analysis, The Post was not only posting vast quantities to Apple News (which at that point did not have any paywall facilities), it was also “all in” on Facebook (The Post’s evolving approach to Facebook is discussed below and shown in Chart 22). Consequently, the proportion of platform-native posts by The Post clocked in at just under 60 percent. Even as The Post embraced native platforms such as Instagram, Instagram Stories, and Snapchat Discover, it put its Apple News channel behind the post-iOS 10 paywall and scaled back its use of native Facebook products such as Live, Instant Articles, and videos. By the final analysis, the proportion of native content pushed out by The Post had fallen below 10 percent.

Chart 19: The proportion of posts “given away” to third-party platforms in the form of native (free/un-paywalled) content.

Unlike most platforms, which are typically either primarily native (i.e., publishers’ posts are hosted and consumed on the platform, e.g., Instagram) or primarily networked (i.e., posts are intended to drive traffic to the publisher’s website, e.g., Twitter, LINE), Facebook has a degree of flexibility.

Facebook Videos, Live videos, photos, etc., are always native to Facebook. However, publishers have a choice when it comes to their articles—they can either post a link that directs the Facebook user to a post on their own website (networked), or upload the content of the article in Facebook’s proprietary format, known as an Instant Article, which is hosted and consumed on Facebook (native).

The chart below shows the proportion of each publisher’s Facebook posts that were designed to live natively on Facebook (Instant Articles, videos, Live, etc.).

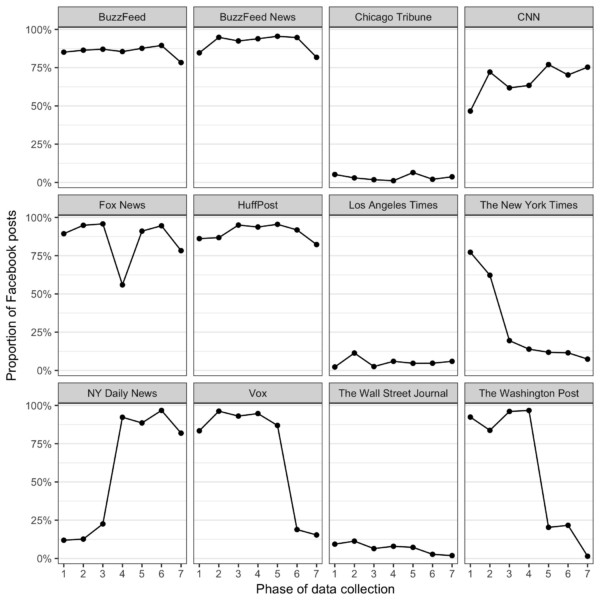

Chart 20: The proportion of each publisher’s Facebook posts that remained native to the platform during each phase of data collection (e.g. native video, Instant Articles, Facebook Live, etc.) (August 2016–March 2018).

Three of the publishers in our study stand out for their retreat from Facebook native—The New York Times, Vox, and The Washington Post. All initially made a majority of their Facebook posts native (albeit to varying degrees). Vox and The Washington Post, in particular, were very much “all in” on Facebook—it was not uncommon for these two publishers to make 90–95 percent of their Facebook posts native to the platform. The proportion of Facebook-native posts made by The Times peaked at 77 percent.

But the three publishers eventually did an about-turn in their approach to Facebook-native content. The New York Times was the first to go cold on Facebook—the proportion of Facebook-native posts had fallen to 19 percent by February 2017. Next was The Washington Post, whose native posts fell from 97 percent in May 2017 to 20 percent in August. Finally, Vox’s plummeted from 87 percent in August 2017 to 19 percent in November 2017. In each case, the proportion of native content reached an all-time low for the publisher by the time of our final analysis in March 2018.

Chart 21: The retreat from native Facebook posts by The New York Times, Vox, and The Washington Post (August 2016–March 2018).

The Washington Post’s change of heart around Facebook-native content is particularly striking and can be traced over time (see Chart 22). During our first analysis, in August 2016, native Facebook content dwarfed networked links back to The Post’s website. This approach continued through the May 2017 analysis, when 97 percent of content posted to Facebook by The Post was designed to be consumed natively on-platform.

However, the tide had turned by August 2017 when, having abandoned Instant Articles, the proportion of Facebook-native posts fell to 22 percent—this native content being made up of 85 videos and eight Live videos. Fast-forward another seven months and all but four of The Post’s 282 Facebook posts were networked links. This meant that just one percent of its Facebook posts for the week were designed to live on Facebook—the remaining 99 percent were intended to drive Facebook users back to The Post’s own websites. In other words, by this point Facebook had become little more than an RSS-style link factory for the publication.

When The Washington Post first partnered with Facebook on its then-nascent Instant Articles in September 2015, a blog from its PR team announced: “The Post will send 100% of its stories to Facebook so that all Washington Post content can be formatted as Instant Articles, giving readers a lightning-fast user experience for reading, sharing and commenting within the Facebook iOS app.” The same announcement quoted Washington Post publisher Fred Ryan saying, “We want to reach current and future readers on all platforms, and we aren’t holding anything back.” Two and a half years later, The Post was holding almost everything back.

Chart 22: The Washington Post’s retreat from almost all forms of native Facebook content.

Diversifying Publisher Strategies

The inseparability of social and search platforms from digital publishing in terms of audience reach and monetization means that the platform-publisher relationship is now a permanent feature of the news ecosystem. Today, it is clear that few news monetization strategies will be complete without platforms. However, the questions are which platforms, how to work with them, and why.

Since our research began, publishers now have a clearer view of what platform product offerings do and don’t include, what each platform’s priorities are, and how they move and change over time. So while long-term platform strategies remain difficult to craft, publishers are beginning to approach monetization more intelligently with the benefit of hindsight. They currently see the key to survival as diversifying revenue streams both on and off social platforms