A piece on NPR’s All Things Considered that aired Monday did little to enlighten listeners about a major change to Social Security rolling rapidly down the pike, an issue that may ultimately find its way into next year’s congressional races.

As those who follow this stuff has know for a while, the president’s budget, released Wednesday, calls for a big change in the way cost of living benefits will be calculated for Social Security recipients (as well as those who receive other government benefits, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, aimed at low income Americans). It’s nickname: Chained CPI, for Consumer Price Index.

To review: The Chained CPI is a way to cut spending and raise revenue. It has been pushed hard by fiscal conservatives and the co-chairs of the president’s deficit commission, former Wyoming Sen. Allen Simpson and former Clinton chief of staff Erskine Bowles, as well as a small group of influential liberals who fear programs like Social Security could eventually crowd out spending on such things as poverty programs or infrastructure investment. Under Chained CPI, Social Security benefits would increase 0.3 percentage points less per year, on average, than under the current formula.

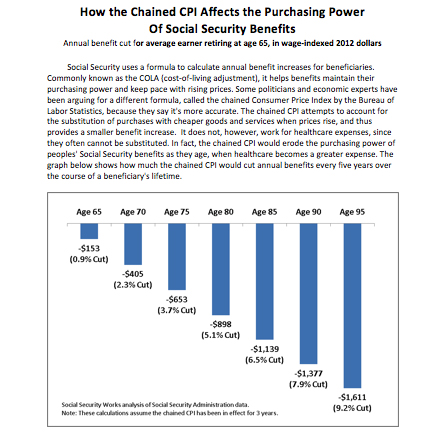

The problem? The slower increase in benefits compounds year after year, so that as a person gets older, the effect is greater. After 10 years, the cut amounts to three percent, and it continues to grow over time. That means the oldest of the old, who sometimes have used up most of their assets, will get the biggest hit. The advocacy group Social Security Works has estimated that the change could mean that an 85-year-old would have $1,139 a year less to live on–not an insignificant sum for people who may hav little money left at this stage of life. Here is a chart showing the loss of income the Chained CPI would bring (click to enlarge):

|

The change, on the other side of the ledger, saves the government gobs of money. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the new calculation method could produce $217 billion in savings over 10 years, with about $145 billion coming from cuts to Social Security and other benefits.

Until recently, the media have pretty much ignored the Chained CPI, and when they have done stories about it, they’ve mostly taken the view that it’s a “technical adjustment”–a characterization NPR’s Scott Horsley allowed the White House spokesman, Jay Carney, to make, without adequately explaining that it is, in fact, more than that. Overall, NPR’s effort on this big development provided the classic “he said-she said” treatment–a framing that is ineffective for a story of this importance and complexity.

Horsley did note that Carney said the president would seek special protections for the oldest seniors. It would have been good for Horsley to tell his listeners exactly what that means. It’s a “modest lump sum,” as The Washington Post described it–Obama’s proposal calls for a universal bump in benefits to the oldest beneficiaries. Still, Social Security advocates believe that you can only soften the blow so much, and that the new CPI would nonetheless hurt many low- and moderate-income people.

To some extent, NPR flirted with the “greedy geezer” meme about seniors and social benefits. Right after annoucing the president’s new budget, the story reported that “there are already protests about it from seniors and others who oppose reductions in spending for Medicare and Social Security.” That seemed to convey the notion the greedy geezers weren’t about to give up anything. After noting the change would result in smaller Social Security adjustments, Horsley moved on to the critics–both pro-Chained CPI and anti-Chained CPI–who Horsley said “are giving lawmakers an earful.”

On one side was Marc Goldwein, identified as from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a group that operates with money from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. Peterson is a long-time critic of Social Security. Goldwein, who is often quoted on these matters, tried to make the wonk case for changing the CPI calculation, noting that the current calculation formula overstates the price increases that consumers actually pay, and “doesn’t have the ability to measure the difference between an apple and an orange or a tangerine.”

The critic from the other side was Max Richtman, who heads the advocacy group the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare. Horsley summed up Richtman’s thinking, saying “if anything, he says, the current measure of inflation understates senior’s costs, especially for things like healthcare.” Richtman didn’t do much to illuminate potential problems with the Chained CPI. The story became a political piece–with Richtman saying his members want no part in such a compromise, but without making the case why the Chained CPI might not be good for many of them. Nor did Richtman or Horsley take the story further and explain how that all of this is related to other parts of Obama’s budget that will make them pay more for their healthcare, even with Medicare.

If NPR were really interested in discussing the Chained CPI, this was an opening to discuss one of its major controversies. The idea behind the proposed measure is to allow for the way people substitute cheaper goods and services when prices rise. As we’ve reported, that kind of calculation may not measure the cost of living with as much accuracy as its advocates promote. Healthcare is the biggest expense for many older persons. Half of all Medicare beneficiaries live on $22,000 or less and spend one-third of their household income on healthcare.

Furthermore, you can’t easily substitute one medical procedure for another. If you need a heart bypass, you can’t substitute a hernia operation the way someone can choose chicken instead of steak. Reporters would do well to go talk to some old people of modest means, and see where their money does go. They might be surprised.

Because of these spending patterns, the government has tinkered with developing a special cost-of-living index based on what seniors actually spend their money on. But neither the press nor the politicians have given that effort any prominence, and the government hasn’t devoted enough resources to measuring and testing it. Which is also worth reporting.

So there you have it. Listeners in NPR-land may be as confused as ever about a change that maybe be moving beyond a Beltway story and into people’s lives. Surely NPR can do better helping them understand what the fuss is all about.

The Second Opinion, CJR’s healthcare desk, is part of our United States Project on the coverage of politics and policy. Follow @USProjectCJR for more posts from this author and the rest of the United States Project team. And follow @Trudy_Lieberman.

Related stories:

Faces the Congress doesn’t see

Medicare Uncovered: Parsing Senator Corker’s big bill