DETROIT, MI — An average time-on-page of nearly 17 minutes. Nearly 50,000 users and 100,000 pageviews, with more than 50 percent of those pageviews from the mobile site or mobile apps—for long stories studded with graphics and interactives. Fifty-two percent of the audience between ages 25 to 34. And an almost incredible bounce rate of .08 percent.

Even as the debate over Web analytics and how best to measure “engagement” continues, that’s a set of numbers that will make any news editor sit up and take notice. The journalism that produced it? “Dividing Lines,” an exhaustive, densely analytical, data-rich four-part series (one, two, three, four) on partisan polarization in metropolitan Milwaukee, produced this month by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Don’t let anyone tell you that wonky political reporting won’t play on the Web—or that it only works in Washington.

The response to the series was “extraordinarily gratifying,” said Thomas Koetting, the paper’s deputy managing editor, who provided metrics to CJR. “People feel like they need this kind of deep information to have intelligent conversations and move the region forward.”

It no doubt helped that, while there are always nits to pick with an effort this ambitious, the series was extraordinarily good—as political journalists around the country were quick to acknowledge. It painted a compelling, and in many ways worrying, picture of a region that is a microcosm of American politics, only distilled and amplified. Partisan polarization, political segregation, and relentless, seemingly intractable conflict have grown across the country over the past generation. Nowhere is that more true than in bright-blue Milwaukee and its deep-red suburbs, which are like rival base camps for the many high-stakes campaigns that roiled Wisconsin over the past few years—including the election, recall, and re-election of Gov. Scott Walker, who understands the dynamic as well as anyone. As reporter Craig Gilbert wrote in the opening of the series: “In its ultrapartisan geography, this is arguably the most polarized place in swing-state America.”

And as Part 3 of “Dividing Lines” makes clear, while that dynamic has real downsides, it paradoxically spurs political engagement—which would have helped whet reader appetites for this sort of granular coverage. A few other unique ingredients were in place as well. In Gilbert, whom CJR dubbed “the most political science-friendly reporter in America,” the Journal Sentinel had a veteran journalist who had witnessed the striking rise in polarization since the 1980s firsthand and documented much of it on his Wisconsin Voter blog. The series was published on a new responsive project template that allowed the paper’s online producers to incorporate interactives and other media inline, unpacking the data where it made the most sense, while also featuring related content. And it was supported by the Marquette University Law School, which is cultivating a role as a leader of civic conversations.

In short: The series represented a major investment, it was the right story for the right time and place, and it was a success.

Which is not to say it was easy. While the series tracks a changing political culture, there are no central characters whose personal narratives pull the reader through. For this sort of work, “the writing is harder than just telling a story,” Gilbert said. Gilbert and Koetting mulled over just about “every word in every phrase,” the editor said, in order to make the writing as clear as possible. The result is clean but dense, sometimes demanding but often rewarding. Even in Milwaukee, the result may not be for everyone (I would have liked a little more narrative myself, and the bland video interviews with voters were one of the few disappointments). It certainly wasn’t optimized for Facebook. But there’s a substantial audience that read every word.

“What we discovered is we need to give readers some credit,” Gilbert said. This is political journalism, he said, that is “not about what both sides say about one another, but is driven by authority because it is fact-based.”

Reader engagement and understanding was supported by some outstanding graphics and interactive maps, created by Allan Vestal, that made the seemingly bottomless data digestible and relieved Gilbert of some of the heavy lifting. And a new project template allowed the paper, for the first time, to incorporate interactive features “within a story as storytelling tools, instead of just as exploratory elements,” said Jennifer Amur, who oversaw the digital design. (In an earlier major series supported by Marquette, interactives and other multimedia open in separate windows. It’s also worth noting here that of course the series ran in print as well, where it would have reached many more readers, even if we don’t have metrics on notes taken in ballpoint pen. Here’s what the first installment looked like on A1.)

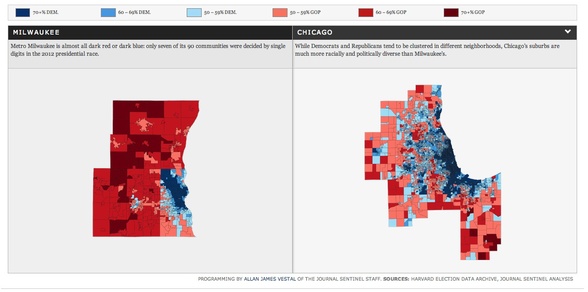

Some of the graphics, like the text, are clear but dense with information. Others are arrestingly simple. These maps, for example, show how the partisan divide in Milwaukee contrasts with relative political diversity in Chicago:

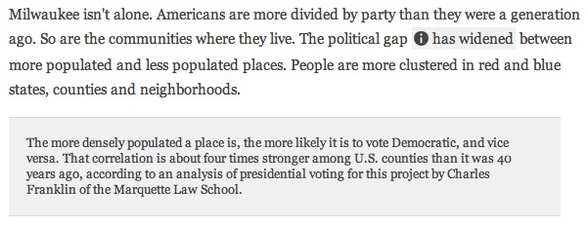

The work was supported by Marquette, which offered Gilbert office space and covered a portion of his salary during a six-month fellowship, so the Journal Sentinel could hire a freelancer to fill in for day-to-day political reporting. The affiliation also created an opportunity for Gilbert to collaborate with Charles Franklin, director of the Marquette Law School Poll, whose research is cited throughout the series, often in in-line footnotes like this:

The law school also hosted a “Dividing Lines” conference at the series’ conclusion; for the especially engaged, full video coverage of the conference is here.

For the Journal Sentinel, the project was a way to develop new platforms and skills. And the paper’s investment, Koetting said, lives beyond the bounds of the series. The market, economic, and demographic information amassed by the reporting is expected to inspire and substantiate future stories.

The project was also a reflection of the paper’s strategic response to the business challenges facing newspapers. Despite the Journal Sentinel’s relative market success and acclaim—it boasts one of the strongest market penetration rates in the country—the paper closed three suburban bureaus and drastically cut staff members through multiple buyouts in recent years. At times, it was a struggle to keep morale up.

Rather than “a nip here, a tuck there,” Koetting said, the paper decided to drop some coverage assignments and focus on three critical areas: breaking news, beat expertise and enterprise reporting, and in-depth investigative/explanatory reporting. “All three of those things are seen through the prism of watchdog journalism,” he said. (CJR has written about the Journal Sentinel’s impressive investigative team.)

“In a way, going through challenging times has forced us to figure out what we’re really, really good at, and focus like a laser on those things,” Koetting added. “When you have a reporter like Craig with a singular expertise, and the ability to do a piece of in-depth, data-driven journalism that can raise the conversation of the entire community, you have to find a way to make it work. That means giving up other things, but at the end of the day, what we gave up is worth it.”

It’s worth noting that, while the series spells out some of the downsides to polarization, “raising the conversation” doesn’t mean “trying to fix the problem.” Though it offers theories, the series never quite makes a case for why polarization is uniquely extreme in Milwaukee. Nor is there a strong sense of “where to go from here”—and from Gilbert’s perspective, that’s purposeful.

“It’s not really designed to be, ‘here’s what we need to do to end polarization,’” Gilbert said. “Wisconsin’s gone through incredible upheaval the last few years. One of the themes of the project is that this is about deep-rooted trends and patterns. It might be a depressing thought, but one of the conclusions was that this is not a fleeting phase in our politics.”

That is depressing—especially given how the political divide Gilbert identifies mirrors other social divides, like race. But even if its conclusions are grim, the existence of “Dividing Lines” is reason for optimism. And the Marquette partnership could be a model, in some markets and for some types of subject matter, of how to sustain this sort of work.

Speaking of which, will another fellowship be forthcoming to the newsroom? The Journal Sentinel isn’t sure yet—but the law school is open to it. At the “Dividing Lines” conference, Koetting said, the dean approached him, smiling, and said, “This was fun. Let’s do it again.”

“I almost grabbed a microphone to get that on tape,” Koetting said, with a laugh.

Anna Clark is a journalist in Detroit. Her writing has appeared in ELLE Magazine, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Next City, and other publications. Anna edited A Detroit Anthology, a Michigan Notable Book, and she was a 2017 Knight-Wallace journalism fellow at the University of Michigan. She is the author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, published by Metropolitan Books, an imprint of Henry Holt. She is online at www.annaclark.net and on Twitter @annaleighclark.