FAIRWAY, KS — It’s no secret: with a few exceptions, newspapers remain way behind the journalistic curve in taking advantage of what the Web can do. But those same newspapers are still a leading source for important investigative and accountability journalism–especially in areas away from major media markets, like the Midwestern states I cover for CJR. The result is that we get a lot of valuable reporting that isn’t, as they say, optimized for digital.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Many newspapers these days are hard-pressed to pay for serious programming and data expertise, but there is a lot you can accomplish with a little creativity and flexibility, and an awareness of how people read online. Here are a few lessons, drawn from some recent special reports that worked well on the Web–and some other instances of good reporting that weren’t as well-served by their digital display.

Link, link, and link some more

The most glaring omission in many newspaper stories as they appear online–and the clearest sign that reporters and editors, even in 2013, aren’t working with the Web in mind–is the lack of hyperlinks. This is true even in major investigative reports. The Kansas City Star‘s series on “Beef’s Raw Edges,” an investigation into food safety published in January, has an attractive landing page, but the stories themselves contain almost no links at all. The same is true in this Des Moines Register series on gun permits published in March and May. This year’s St. Louis Post-Dispatch series on Missouri soldiers in Afghanistan does feature related links in a sidebar, as most P-D online stories do, but no links in the story text itself.

The lack of hyperlinks is, above all, a huge missed opportunity for self-promotion. An online news package needs well-placed links to move the reader from one story to the next. Internal links are the best way to keep readers on-site.

To see internal linking done right, check out this article from the Tampa Bay Times‘ award-winning 2012 “Stand Your Ground” series, which features no fewer than 12 links embedded in the text leading to other stories in the series–in addition to a half-dozen sidebar links to related content. This kind of Web curation takes a little time to do, but it makes it that much easier for the interested reader to discover all of the hard work your staffers have done on stories of this magnitude.

But internal links are not enough. For the investigative journalist, external links can be particularly useful. The best way to substantiate your reporting is to link to your source material.

This summer, in an ongoing probe into mass-transit contracting practices, the San Diego-based investigative nonprofit inewsource.org tried a novel approach to linking. Reporter Brad Racino offered readers two versions of the same June 13 story, one with minimal hyperlinks and another with links in nearly every sentence–as seen here.

This approach allowed Racino to substantiate his reporting by linking to all of his source material, while not overwhelming readers who might be put off by so much hypertext. As it turned out, he later wrote, the hyper-hyperlinked version drew more page-views and longer visits than the conventional version.

Show your work

Most of the links in Racino’s story were to materials uploaded via DocumentCloud. This service, and others such as Scribd, make it easy for journalists to upload primary documents that substantiate their investigative work and share them with their readers.

For the KC Star report on the beef industry, the editors noted that “reporters … studied thousands of pages of documents obtained through a dozen state and federal open records requests and pored over thousands of pages of lawsuits, scientific studies, government audits and research reports.” But while a single, large, un-annotated PDF file was linked from the landing page–where it was confusingly labeled a “graphic”–none of these hard-won documents are linked in the stories themselves.

The Des Moines Register gun series did link to source material posted via DocumentCloud–and in one case used an annotation to draw readers’ attention to the relevant portion of a document–but buried the links at the bottom of an article rather than embedding them in the appropriate text in the body.

For investigative reports, such documents can and should receive more prominent placement. A 2010-2011 series in the Memphis Commercial Appeal, which revealed a prominent Civil Rights Movement photographer’s role as a longtime FBI informant, linked to dozens of materials uploaded via DocumentCloud in individual stories and highlighted them on the landing page as well:

Reporter Marc Perrusquia doggedly compiled FBI reports in investigating the photographer, and his colleague Grant Smith undertook the work of uploading the document archive for readers to see.

Many readers, of course, will have little interest in getting this far into the weeds on a story. But even for them, the presence of such documents builds credibility, which is the most basic prerequisite for the successful investigative reporter. And the deeply engaged readers who are interested in looking at such documents will spend that much more time on the site, and be that much more likely to return.

Hang out and chat awhile

Another advantage the Web can offer for a major investigative package is a variety of different platforms to get the message out. Newspapers have made great strides in adopting video reports and slideshows as part of their toolbox–the Star, the Post-Dispatch, and the Register have each effectively used these techniques in their packages. But video and photographs are still conventional, old-media reporting formats migrated to the Web.

By contrast, online video, audio and text-based chats offer reporters the opportunity to communicate in a more relaxed, direct, and casual voice than they can within the time, space, cost constraints, and stylistic conventions of print and TV venues.

To be fair, that opportunity may fill some tradition-minded reporters with dread. But contemporary journalism demands that we communicate directly with readers, explain our work, and hear feedback. See, for instance, this live chat from last year conducted by Seattle Times investigative reporter Christine Willmsen regarding her series on indefinite detention of sex offenders. Willmsen had to know ahead of time that it could be a bumpy ride given the uncomfortable subject matter–and indeed, many of the questions in the one-hour session were antagonistic. But the honest exchange provided a valuable user experience in fleshing out the implications of the controversial story.

For a less stressful chat option, journalists looking to enhance their investigative series might consider Google Hangouts, which offer a low-cost, low-tech venue for video exchanges between reporters and their colleagues. My United States Project colleague Joel Campbell recently highlighted the Salt Lake Tribune‘s use of Google Hangouts to supplement an investigative series on a scandal in the Utah attorney general’s office. Time magazine also hosted a Google Hangout in February with Steven Brill, in which he discussed the reaction to his “Bitter Pill” cover story on medical costs.

These free-form, unedited conversations won’t suit every taste, but many users may find them more accessible and less daunting than traditional news pieces. Plenty of Star, Register, and Post-Dispatch readers would surely appreciate the opportunity to hear ace reporters like Mike McGraw, Jason Clayworth, and Jesse Bogan discuss their work and its larger implications in a relaxed, unhurried format.

Make it pop

A final piece of the puzzle in assembling a special report–and one that can require some expertise–is to make it visually arresting. On the Web, this means not only creating appealing graphic images but endowing them with dynamism and interactivity.

See, for instance, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel‘s interactive map identifying infant mortality statistics within the city by ZIP code–an invaluable supplement to the paper’s ongoing “Empty Cradles” series. This tool allowed users to select for various healthcare data in their own neighborhoods.

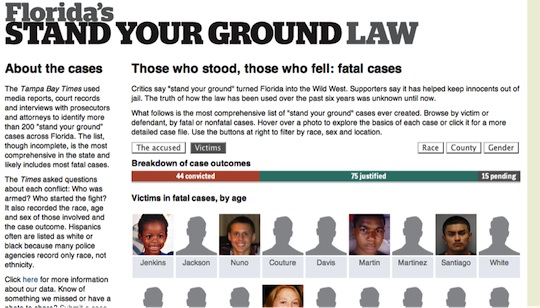

The Tampa Bay Times‘ “Stand Your Ground” series offered another impressive interactive feature with its database of case files, which revealed that the Trayvon Martin case is only one among hundreds that have been affected by Florida’s controversial self-defense statute:

Users can sort cases by race, county, and gender; view a gallery of the accused in each case or the victim; and roll over each mug shot to see a detailed account of each case at the left side of the screen. And each mug links to a separate case file–the same files that provided most of the 12 links in the story I mentioned earlier.

The Post-Dispatch, to its credit, uses a similar feature to tell the stories of St. Louis-area soldiers who have been killed in Iraq and Afghanistan, but the page architecture is a letdown. Reading the capsule bios of soldiers below the first few rows means scrolling down to a thumbnail picture, clicking on it, then scrolling back up to the top of the page for the info and links to related stories.

Of the three Midwestern papers singled out here, the Register stands out for its use of interactive graphics, with a clickable state map that allows users to see gun-permit statistics by county. We can only hope that features like this one point the way to more creative work from legacy news organizations in the region and beyond.

Of course, the ideal scenario–indeed, the inevitable one, if newspapers are going to survive–is that reporters and editors conceive and write all of their stories with the Web in mind. This could eventually mean, among other things, a reconsideration of conventional storytelling methods–perhaps a shift away from the AP-style newswriting voice altogether. In the meantime, the Web offers plenty of low-hanging fruit that newspapers can grab to bolster their reporting. Everyone in the newspaper business knows the difficulties presented by the Web. But too few are embracing its benefits.

Deron Lee is CJR’s correspondent for Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska. A writer and copy editor who has spent nine years with the National Journal Group, he has also contributed to The Hotline and the Lawrence Journal-World. He lives in the Kansas City area. Follow him on Twitter at @deron_lee.