The media has undergone a strange change of mindset. Immediately before last Tuesday’s election, many reporters and commentators ignored or dismissed the consensus among forecasters and betting markets that President Obama was very likely to defeat Mitt Romney and acted instead as if the candidates were neck and neck or Romney was ahead. Afterward, however, coverage of how Obama won betrayed far less uncertainty about the outcome of the election, which was frequently portrayed as a fait accompli—an inevitable consequence of how Romney’s image was defined by Obama’s early ads or overwhelmed by the President’s superior ground game.

Before the election, for instance, Wall Street Journal editorial page editor Paul Gigot said on the October 27th edition of Journal Editorial Report that “Polls continue to show the race in a dead heat nationally, and too close to call in no fewer than 10 swing states.” Afterward, however, Gigot asserted on ABC’s This Week that while Romney “could have won,” he “never recovered” from the negative ads Obama’s campaign ran against him during the summer. “[I]f he wanted to win, clearly they needed to respond somehow, and they didn’t.”

Similarly, National Journal‘s Michael Hirsh declared after the election that “perhaps the most successful chunk of advertising money ever spent in modern American political history was the initial $50 million or so the Obama team devoted last spring to defining Romney as an exploitative, job-exporting Wall Street plutocrat.” While his lede states that “Romney could have won,” he approvingly quotes GOP strategist Rick Tyler saying “The early ads paid off… I don’t think [Romney] ever really recovered.” But just a few weeks ago, Hirsh described Obama as “an imperiled incumbent who faces a must-win situation” in his second debate with Romney and later described Hurricane Sandy as necessary to stop Romney’s (mythical) “momentum.”

ABC/Washington Post pundit George Will went even further than Gigot or Hirsh before the election in predicting a Romney win with 321 Electoral College votes. When that prediction was falsified, Will reversed course and declared that the outcome was “foreshadowed by Mitt Romney struggling as long as he did to surmount a notably weak field of Republican rivals.” The foreshadowing was apparently more obvious in retrospect than it had been five days earlier when he made his prediction.

This pattern of seeing an outcome as inevitable in retrospect, which is known as “hindsight bias,” was unfortunately all too predictable (and not just in hindsight!)—here’s what the New York Times‘s Benedict Carey wrote before the election:

Amid the many uncertainties of next Tuesday’s presidential election lies one sure thing: Many people will feel in their gut that they knew the result all along. Not only felt it coming, but swear they predicted it beforehand—remember?—and probably more than once.

These analysts won’t be hard to find. They will most likely include (in addition to news media pundits) neighbors, friends, co-workers and relatives, as well as the person whose reflection appears in the glare of the laptop screen. Most will also have a ready-made argument for why it was inevitable that Mitt Romney, or Barack Obama, won—displaying the sort of false, after-the-fact “foresight” that psychologists call hindsight bias.

The hindsight bias we have seen is fueled in part by the wave of post-election spin that follows every election. Inevitably, the press reports, as it has this time around, that the winner won due to the strategic genius of the candidate and his campaign (often based on source-greasing interviews with staffers taking a victory lap) and the loser lost due to disarray and mistakes within his campaign (typically fueled by internal leaks seeking to deflect blame).

Still, many political observers seem to struggle to understand how hindsight bias is clouding their judgments and the media’s coverage. It can be difficult to imagine the stories we would be seeing now if Romney had won, for instance. That’s why it’s instructive to consider Politico’s premortem on how an Obama loss would be interpreted, which seems like a plausible counterfactual account of the stories that would now be circulating. (They also wrote a Romney premortem that didn’t anticipate the emphasis that would be given to Obama’s ads and the ground game.) Or consider the story of the 2004 election. According to an American Journalism Review article, reporters relying on flawed exit polls ended up writing stories “explaining” why Kerry won that had to be replaced by alternate accounts recounting how Bush won a narrow victory:

Like their TV counterparts, many newspaper reporters saw early exit polls, and some crafted preliminary stories relying on those numbers.

Jack Torry, a Washington reporter for Ohio’s Columbus Dispatch, helped write two different analysis stories on election night. The first, never published, was based on late afternoon exit polls and explored how Kerry won the election, a “referendum on President Bush.”

“The more I kept checking with Republican sources who I really do trust, the more I began to wonder: Could those exit polls be right?” Torry says. He and his colleagues scrapped the first piece around 9:30 p.m. Their second analysis, which actually appeared in the paper, examined why the race was so tight.

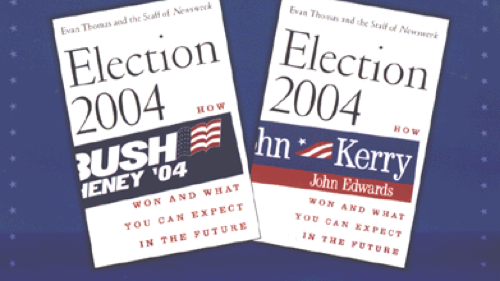

Before that election, Newsweek went so far as to promote two different versions of a post-campaign book about how either Bush or Kerry won before the election had even happened—check out this amazing image:

A similar process of retrospective justification would have likely ensued among observers had Kerry’s reported lead held up.

Of course, it may actually be true that Obama won this election because of his superior ground game or devastating barrage of negative advertising, but convincing evidence does not yet exist to support either claim. Obama performed about as well as we would have expected given the political and economic fundamentals of the race. Until proven otherwise, little credence should be given to post-election narratives that are constructed after the fact to “explain” the outcome we have observed.

Brendan Nyhan is an assistant professor of government at Dartmouth College. He blogs at brendan-nyhan.com and tweets @BrendanNyhan.