Except for Los Angeles Times columnist Michael Hiltzik, and a few stray media outlets here and there—The Providence Journal, The Palm Beach Post and, of course, The Washington Post—there had been little media attention to possible changes in the way Social Security cost-of-living adjustments would be calculated. That is, until the last several days. Almost as if on cue, Beltway columnists came forth with their takes on what is called the “chained CPI,” a method of calculation that is near the top of the wish list for DC deficit hawks and budget cutters.

Why is the chained CPI (chained Consumer Price Index) so attractive to such people? As we reported a couple of weeks ago, it cuts spending and raises revenue. The Congressional Budget Office Office estimates it could produce some $217 billion in savings over ten years, with about $145 billion coming from cuts to Social Security benefits and other government pensions.

It’s a juicy target for another reason, too: the public knows next to nothing about it. Its obscurity may have led Slate to characterize it as “the sneaky plan to cut Social Security.” The headline on a blog post by The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson called it “The Sneaky, Complicated Idea That Could End the Fiscal Cliff Showdown.”

Whether that will happen is very much up in the air at the moment. Some Washington writers and columnists aren’t keen on the idea. The idea behind “chaining” is to allow for the way people substitute cheaper goods and services when prices rise. Timothy Noah, writing for The New Republic blog, gave a good description of why the Chained CPI may not measure the cost of living with as much accuracy as its advocates promote. “Would chaining really bring Social Security benefit increases in line with spending patterns? Actually no,” he argues, pointing out that the proposed index doesn’t deal with healthcare spending very well. Healthcare is the biggest expense for many of the elderly, and consumes a larger share of their budgets than does for the rest of the population. If you need a heart bypass, you can’t substitute a hernia operation, the way someone might substitute chicken for steak.

While it didn’t take a position on the proposed formula, the National Journal’s good reporting clearly explained what the new index was all about. It noted the drawbacks of making a change, even quoting Andrew Biggs, a resident scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute and former principal deputy commissioner of the Social Security Administration, who expressed serious doubts about switching over to the chained CPI. “One reason is, it’s not based on the purchasing habits of the elderly,” Biggs said. “The consumption patterns of a working household aren’t the same as the consumption patterns of, say, an 85-year-old Alzheimer’s patient living on a fixed income.”

Others in the media seemed to be in the “on the one hand, on the other hand” mode. Count Matthew Yglesias in Slate and Thompson in The Atlantic in this camp. Says Thompson at the very end of his post:

There is a real risk that low-income seniors who live long lives could see smaller Social Security checks than they would today. But if this moderate and slow-moving deficit saver is the linchpin to an otherwise fair deal, Republicans and Democrats can do much worse than adopting a chained CPI.

It’s too early to tell whether media resistance to the chained CPI is a mini meme in the making, but as CJR has urged, the press is beginning to examine what it will and won’t do, and how it will affect America’s oldest and most vulnerable citizens.

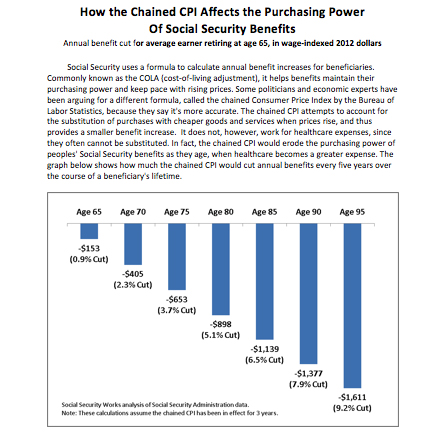

Here’s the short version: Chained CPI increases benefits 0.3 percentage points less, on average, each year than the current cost-of-living formula, according to Social Security’s chief actuary. Importantly, the slower increase in benefits adds up each year, so that as a person gets older, the effect is greater.

The advocacy group Social Security Works estimates that a person age 75 in the future will get a yearly benefit that’s $653 lower after ten years of chained CPI than that person would get under the current formula. An 85-year-old will have $1,139 less to live on. While this doesn’t seem like a princely sum to an investment banker, it is to the very old.

(See the chart below; click to enlarge).

|

Speaking to a group of journalists this week at Columbia University, Sherry Glied, a professor at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health, pointed out that “the ‘older old’ outlive their assets and need long-term care and home care.” Public policy has to work for these groups, she said, and she urged reporters to look at how various prescriptions to fix the deficit affect the different groups of the elderly who have different needs and financial assets.

The ‘younger elderly’—the 66 and 67-year-olds—may be okay financially for the time being, since the chained CPI won’t substantially affect them for years, and they have not outlived their assets. That makes it easier medicine for policy makers to swallow.

Some chained CPI advocates believe that the very old—the ones WaPo calls “those who are well into their 80s,” could receive “a modest lump sum” to help them over their financial hump. The Simpson-Bowles blueprint proposed that those in this age group receive a small increase after they’ve been getting Social Security checks for 20 years.

Will this be enough? Who knows? In theory, it sounds like it solves a problem. In practice, it may not. Imagine 85 year olds barely able to walk having to show up at a Social Security office clutching financial documents, along with the light bill, to prove they are poor enough for the modest lump sum! Opponents argue that’s not what Social Security is about, and the media are beginning to report on that side effect.

Follow our coverage of the coverage of politics and policy on Twitter @CJRSwingStates. And follow the author @Trudy_Lieberman.

Related stories:

Can people afford to lose their Social Security COLA?

What a higher Retirement Age really means

Dart: CBS and the Goldman Sachs solution

Trudy Lieberman is a longtime contributing editor to the Columbia Journalism Review. She is the lead writer for CJR's Covering the Health Care Fight. She also blogs for Health News Review and the Center for Health Journalism. Follow her on Twitter @Trudy_Lieberman.