SOUTH CAROLINA — The campaign media horde congregated in Charleston Thursday night for the Republican presidential debate, eagerly billed by host network CNN as the “First in the South.” I was there, too—not for the debate, but for the horde. There were about three hundred of us in all, lined up at our stations in the filing center, glancing between large screens (the TV monitors showing the debate occurring in the adjacent hall) and small ones (computers, tablets, smartphones).

The whole scene kind of reminded me of industrial farming. Here’s how the sausage gets made.

CNN opened the doors of the North Charleston Coliseum to credentialed journalists at noon, and at three offered a sneak preview of the debate hall. Possibly because it was so early, possibly because this was the twenty-third debate of the season, or possibly just because news reporters have better things to do, the tour group consisted of a few international reporters, some local television crews, myself, and twelve-year old twins from Daniel Island, S.C., who were on assignment for the Scholastic Kids Press Corps.

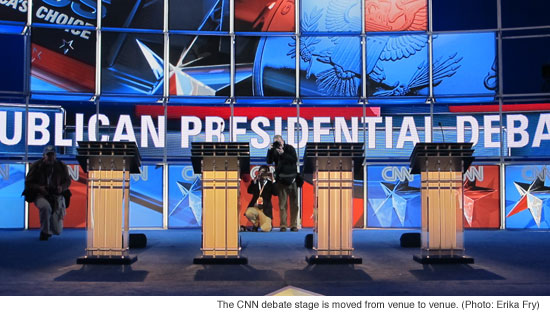

Sam Feist, CNN’s Washington bureau chief and executive producer of the debate, played tour guide. He told us it was the same set that CNN has used at all the other debates this year—it’s just packed up and moved from place to place. He encouraged us to feel the carpet, still cold from the ice lying beneath it (the Coliseum is home to the South Carolina Stingrays, a minor league team in the East Coast Hockey League). And he told us it had been a wild day in debate-planning: the CNN crew had learned that morning that Mitt Romney hadn’t really won the Iowa caucuses, and that Rick Perry, who was supposed to occupy the furthest podium at stage right and receive a fifth of the night’s questions, had dropped out of the race. (Not to mention the interview given by Newt Gingrich’s second ex-wife to ABC, in which she said he’d asked for an “open marriage.”) The moderators had been busily working on more queries for the remaining candidates.

Feist pointed out the red chairs in the center of the debate hall, which would be filled by select audience members who might get the chance to ask a live question at the debate. (When I asked how the lucky questioners were chosen, a CNN spokeswoman didn’t seem eager to tell me the secrets of the sauce, but left it at, “They are vetted very carefully—to make sure they’re not part of any campaign.”) The red chairs were ringed by tiers of blue ones, which had been labeled with masking tape bearing the names of various VIPs—politicians, conservative bigwigs, candidates’ spouses, CNN personnel. South Carolina governor Nikki Haley’s chair was starred. Beyond the blue seats was the arena seating that would be filled by two thousand audience members.

I asked whether the audience was briefed on how to react during the debate. Yes, I was told—audience members would be encouraged to applaud and react, but to do so respectfully. The producers said they’d had no problems with disrespectful audiences in previous debates this year. (Huh.) The tour concluded on the stage itself, where the podiums were labeled with small nametags—Rick Santorum, Mitt Romney, Newt Gingrich, Ron Paul. Many of the journalists took turns being photographed behind the podiums.

Then it was back to the filing center, which by about seven o’clock was starting to fill up with reporters reading, checking e-mail, and eating sandwiches out of Styrofoam boxes. The assembled journalists were arranged roughly by media type. Up front were the wire reporters (as well as the Scholastic kids), followed by the newspaper reporters, followed by the weekly magazines, followed by the monthly magazines. Behind them, the internationals. Then, in the far back corner, the bloggers, working more constantly and frantically than anybody else. There seemed to be more bloggers than chairs. (The seating arrangement put me back center, between seats reserved for Vanity Fair and CQ, each of which remained empty.)

Around 20 minutes before the 8 p.m. start time, the pre-game festivities began in the debate hall. Governor Nikki Haley spoke, and the Pledge of Allegiance was recited. If you’ve ever been in a studio audience, what happened next will be familiar: an enthusiastic, muscular man, wearing a headset and all black—he looked like a burglar, or maybe a Tae Bo instructor—came out and baited the audience. “Who wants to be on TV tonight?” He encouraged them to applaud energetically—“We want to feel your love!” “We want to hear your hands clapping!”—but to avoid heckling, shouting, and standing.

Meanwhile the reporters, most of whom must have seen this routine many times over, were making last-minute runs to the food table. But just about every journalist was settled into his or her seat and had opened up Twitter—Tweetdeck or Hootsuite for the younger and more tech-savvy in the room—by the time CNN’s intro package went on air. Santorum was pronounced to have “renewed momentum”; Paul, “an insurgent army of young people.” And just in case you forgot where we were: “Welcome to the South” (“where values matter”). The reporters in the room seem to relish the hokiness of these promos; snarky 140-character comments are de rigeur.

And with the action underway, the wild tweeting (and more) began. For most journalists in the filing center—my row excepted; some of my fellow monthly magazine colleagues didn’t even bring a computer—it’s no longer enough to sit, watch, and then write quickly about the debate. There is also the tweeting, live-blogging, storifying, and simultaneous fact-checking that is part of debate coverage. I have no idea how they do it; I struggle to merely read Twitter as I process what the candidates are saying.

I also have little idea who reads all of this in real time, other than the journalists themselves. It is an odd experience to sit in a large, often silent room with three hundred people who are furiously tweeting, retweeting, and reply-tweeting to each other (and their professional peers who aren’t in the room)—cracking jokes, settling on sound bites, ranking candidate performances and ties. While there’s certainly a little (very little, in 140 characters) debate in these exchanges, there is far more consensus-building. This is how the hivemind is made.

As you’ve heard by now, the debate got off to a fiery start. (So much for those audience ground rules.) In the filing room, the journalists—the despicable “elite media” all in one place!—appeared to be more entertained by the theatrics of Newt Gingrich’s angry denunciation of moderator John King and the press corps than insulted by its substance. There were lots of laughs in the room (it’s not entirely silent); Twitter went wild. The consensus seemed to be that Gingrich had handled the episode marvelously.

There were plenty of laughs over the next hour, too, most prompted when a candidate’s tics came to the surface. Newt attacks the media; Newt invites a “Lincoln-Douglas debate”; Romney reminds everyone how long he’s been married; Romney says he’s from the “real streets” of America; Ron Paul gets ignored and ignored and ignored.

At 9:02, my closest seatmate, Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi, got up and left (or at least relocated). This was not long after he buried his head in hands in reaction to Romney’s “real streets” comment.

That flagging spirit seemed to have infected the room by about 9:15—there was more milling about; less tweeting. By ten o’clock, the debate was done.

The work is hardly over when the debate is, though. That’s the signal for journalists to begin the oddest portion of their night: time in the “spin room.” Think the concept of “spin” is antithetical to journalism? That’s not the case here, where most of the reporters herded into an adjacent room with their cameras and equipment. Surrogates for each of the candidates stood beneath signs held up by unfortunate young staffers, waiting to be approached by journalists. (At each station, a second employee was dispatched to hold a “CNN Politics” sign.) You know these folks are going to say something positive—the only suspense is how they get there.

Romney backer Tim Pawlenty, for example, when asked about Romney’s “maybe” moment, said his candidate’s stated plans to release his tax returns far surpass those of any other: Gingrich has just released his returns for one year, Santorum gave a “non-answer,” and Paul doesn’t have any plan to release his.

And Pawlenty, no surprise, thought King’s opening question about Gingrich’s ex-wife’s comments was A-OK. “It was the lead story of the day,” he said.

When a reporter followed that up with, “How do you think Governor Romney did tonight?” I left and headed over to the Gingrich section. Gingrich’s press secretary, R.C. Hammond, was telling journalists how inappropriate King’s question was.

It’s probably worth considering how much value this sort of commentary adds, but in the moment, there’s not a lot of time for that. The spin room is a crush of people, and the best strategy is to quickly glob on to the scrum, thrust out your recorder, and push to the front. If the filing center is journalists in their pens, the spin room is reporters at the feeding trough. (Or, in the words of Scholastic Kid Reporter Zach Dalzell, the reporters were “swarming… like bees at the smell of honey.”)

By 10:40, the spin room crowd had thinned out and reporters were returning to their places to file their stories. Being a writer for a bimonthly magazine, I did what seemed like the sensible thing—went home to get some sleep.

Erika Fry is a former assistant editor at CJR.