Before an otherwise unremarkable preseason game in August 2016, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick sat quietly on the sideline bench while his teammates stood for the National Anthem. The protest movement launched by that decision has since engulfed the national conversation surrounding the NFL, spread to other sports, and drawn attacks from the president.

What began as a protest against police brutality and unequal treatment of minorities in America has morphed into a controversy over free speech, patriotism, and who gets to control the narrative. During the current iteration of the debate, one voice has been missing: Colin Kaepernick’s.

Last spring, the writer Rembert Browne set out to tell Kaepernick’s story. The freelancer, who previously worked for Grantland and New York magazine, believed that he would have the chance to spend time with Kaepernick and those in his circle for a Bleacher Report feature. But as spring stretched into summer, it became apparent Kaepernick wasn’t interested in participating.

ICYMI: ESPN suspended Jemele Hill. We now know the network’s 1st and foremost goal

Initially frustrated, Browne ultimately realized that Kaepernick’s silence allowed for a more nuanced, creative piece. He visited Kaepernick’s hometown of Turlock, California, spoke with activists and NFL players who followed Kaepernick’s lead, and wrote a 10,000 word essay, “Colin Kaepernick Has A Job,” that addresses not just the quarterback’s protest, but meditates on important questions about what it means to be black in America in 2017.

What follows is another installment of Behind the Story, in which we’re given a peek behind the curtain at how a story was conceived, reported, written, and edited—as told to CJR by the author, Rembert Browne.

***

The guy who runs Bleacher Report Magazine, Matt Sullivan, approached me. He said they had been warming up to Kaepernick’s camp. It’s what you have to do in the access-y journalism world, be it sports, music, or whatever. If you want the interview you have to go through the camp, the managers, the publicist. It’s kind of a shitty world, but that’s how it works.

I had only been freelancing for two months. I was trying to figure out what my summer was going to entail. They pitched it as a summer-long project that would be coming out in the fall. I was like, “I would love to do the Kaepernick profile.” It was kind of pitched that this was going to be the only thing that he was going to do. That’s what got me to say yes.

That began a process of trying to get in contact with him. Not just me, people at BR who had some connections with Colin’s girlfriend, Nessa. But after a month, a month and a half—we’re in May now—nothing had happened. There had been some communication but nothing that seemed like they were remotely in to do this piece.

I really hadn’t started doing any work on it at that point. I was treating it the way I had treated any other profile I had done. I was actually working on another profile at the same time, a Lil Yachty piece for Fader. That was very much a Come out to LA, hang out with Yachty for a week. Talk to him, shadow him, you get all your notes and then you leave and write your piece. I was kind of in the same mindset with this, but that’s not how it was playing out.

April became May became June. I see he’s in Africa. In my head I’m like, I don’t really know if this is gonna happen. What is this piece gonna turn into? At that point, I started thinking I still want to write this piece, and they’re still paying me, I gotta figure out something.

Rembert Browne. Photo credit: Naima Green

I wasn’t thinking about it as a write-around. I was more thinking about writing a piece on someone without the access to him. As more of a creative writer than a journalist, I was fine with that.

At first it was frustration just because it was a shot to my ego. It was like, “What’s wrong with y’all?” Any background research you do on me will show you I’m kind of on your side. I can still push you, but I’m not here to roast you. That’s where my ego was, where I thought it was very foolish on their part.

Then I realized: They don’t need to talk to me. They’ve got their whole thing going, and they’re doing it right. It became super freeing.

I’m not saying this is true for everyone, but for me it is always going to be hard to have been given access by someone to talk to them, and to then be hypercritical to them once I leave. It’s just hard for me. So not having to do that, and by talking to the people around him, I thought I could do and say whatever I wanted and be fair.

There are things in this piece that people who want the perfect Colin Kaepernick narrative weren’t thrilled about. There are critical moments. But … this paints him in a much more important way than a puff piece of propaganda from access journalism.

BEHIND THE STORY: ‘The white flight of Derek Black’ by Eli Saslow

I’m becoming a better reporter, but I’m not a reporter by trade. I don’t love interviewing people. A lot of my biggest social anxieties come out from reporting, like bothering people to talk to me and tracking people down and sometimes asking them questions they’ve already been asked. All those things that make you a good reporter make me uncomfortable.

I was like, Well, maybe I should just start talking to other people. I had begun to get in contact with people like John Legend, DeRay Mckesson. I was trying to reach out to the celebrity cohort of people he seemed to be talking to, and that was giving me good stuff, but I knew that wasn’t going to be enough.

That’s when I got to the idea of Fuck it, what’s a good scene I haven’t read about? Let me go out to his hometown.

I wrote a profile of Colin Kaepernick.

I wrote an essay about America. https://t.co/jGCFaLU4zC— Rembert Browne (@rembert) September 12, 2017

I didn’t have anyone to talk to in Turlock, I just wanted to get a sense of what that place was like. I’ve done that. I have a lot of experience writing event pieces, going to towns and places and feeling them out and writing about them. I enjoy doing that; it feels very organic.

I did what I typically do in these situations. I go to a bar, listen, talk to bartenders. That’s always, for me, the easiest way to get a sense of a town and a place—a bar, especially, in this case, a sports bar. The social lubricant of a bar often makes them more accepting than the outside world.

I didn’t feel uncomfortable, or like anyone was giving me weird looks. It was just very clear that I wasn’t from there. I wasn’t fooling anyone. Even if I wasn’t from Atlanta and living in New York, I’m just clearly not from Turlock.

I was only there for a day. I hate when people try to fully explain a town after spending four hours there. That wasn’t the goal. It was just to look around and say, OK, this is where he grew up. Interesting. Noted.

I read a lot from the local Turlock papers, but by being there I felt like I was more capable of diving into what it must have been like to be him in a place that simultaneously should have erected statues to him for being the most famous person, but where walking around, there was little to no evidence he ever existed. That was something I needed to see to begin to feel things when it came to writing this piece.

By the time I left Turlock, I didn’t have much. But I went to college with a kid, Taylor, who I remembered out of nowhere was from Turlock. I was sitting in the parking lot of a Goodwill, where I had just bought some T-shirts, and I hit up Taylor on Facebook Messenger. He was maybe a year above Kaepernick in high school.

I wanted some perspective on the town. Taylor basically said, “I don’t have a great perspective; I haven’t been there in a long time, but I have a friend who is a journalist whose family grew up close to the Kaepernicks.” So he connected me to him, and I talked to that guy. He hadn’t been home for a while either, but he told me his dad still lives there, and knows the Kaepernicks well.

That was the first big inroad I made in terms of an actual, super important interview in terms of getting the perspective of someone who knew the family and could explain what Turlock was like while Colin was a star and what it was like now. After that I realized OK, this is going somewhere. This piece is actually happening.

I talked to [political activist Ameer “Left” Loggins, a friend and adviser to Kaepernick] in August, a week or two after I got back from the Bay. He was great. When you talk to people like him or someone like DeRay, they’re just really fucking smart. It was awesome to talk with someone like Left, who gave me more than he needed to, because I think he felt I was someone who could do this story justice. Talking to him was something else that made it like, even though I can’t talk to Colin, I got a lot of stuff that will help make this be a real piece.

I straddle this line of being a chronicler of events, a journalist, a writer. But other times I am in the mix. There are people and things I can’t write about objectively because I know a lot of people. I couldn’t write a profile on DeRay, because I know him. That’s one of the reasons it’s hard for me to think of myself being an objective journalist in ten years because I like working with these people.

Last night was mad real. pic.twitter.com/SQsFHsWQzJ

— Travon Free (@Travon) August 2, 2017

I care about things being better a lot more than I care about being a journalist, and sometimes my greatest impact is doing behind-the-scenes work, not writing about people from a distance. I saw a photo of Kaepernick, Hasan Minaj, J. Cole and Travon [Free]. There’s a world in which, if I’m not writing about Kaepernick, I might be in that room. I saw a photo of DeRay and Kaepernick and Jack [Dorsey]. There’s a world in which, if I’m working on something else, I could talk to those three. But because I was working on this thing, that wasn’t my time to be in the inner circle. I have to be very clear about who I am in the moment.

I had a lot of time to think. I didn’t write for those first three months, but I had a lot of time I was thinking about the ideas.

They were like, “We need some fucking words.” So I started writing.

I had this [James] Baldwin profile of [Martin Luther] King that I was kind of using as a guide. While he got to King, it was also observational. That piece was about a man in a moment in time in America, ’61, young King. Kaepernick’s about to turn 30; King was 32 at the time. There was a lot of Baldwin doing—not necessarily theorizing—but being like, This is what it must be like to be him, watching people around him, being in the room, being trusted but not being allowed in the circle.

That piece was about the country. It’s about America at a moment. I was like, OK, that’s what this piece is going to be about.

So I was reading Baldwin, and some screenplays. I reread Rachel Ghansah’s Chappelle thing—I’ve read it like 20 times—and I read, obviously, the Sinatra piece. Those are the two examples of write-arounds that have held up.

I was reading those less from the view of how to write the piece and more because there were some things that kept me interested and kept me going—the way sections started. I love writing long, run-on sentences, especially to get a section going, or starting with quotes. Little tricks like that. I was looking for ways to keep someone continuing to scroll down.

Something else I was using to think about the structure was O.J.: Made in America. Ezra (Edelman, the documentary’s director) is so smart about the way he did that because he would do an O.J. thing, and then talk about LA for like 45 minutes before coming back to O.J. I went back and rewatched it because it worked, obviously.

I’m a West Wing person. I used to be a work all day, all night person, and it was really messing with my mental health. On the West Wing, people have these crazy days. It’s insane. But then at some point, toward the end of the day, they’re like, “We tried our hardest. Let’s try again tomorrow.” So now I have an ending time. I can’t do work literally anytime past 7 pm. I try to have these condensed, super mentally intense, passionate days and just try my hardest. Not to be a dick about deadlines or anything, I’m just trying my hardest.

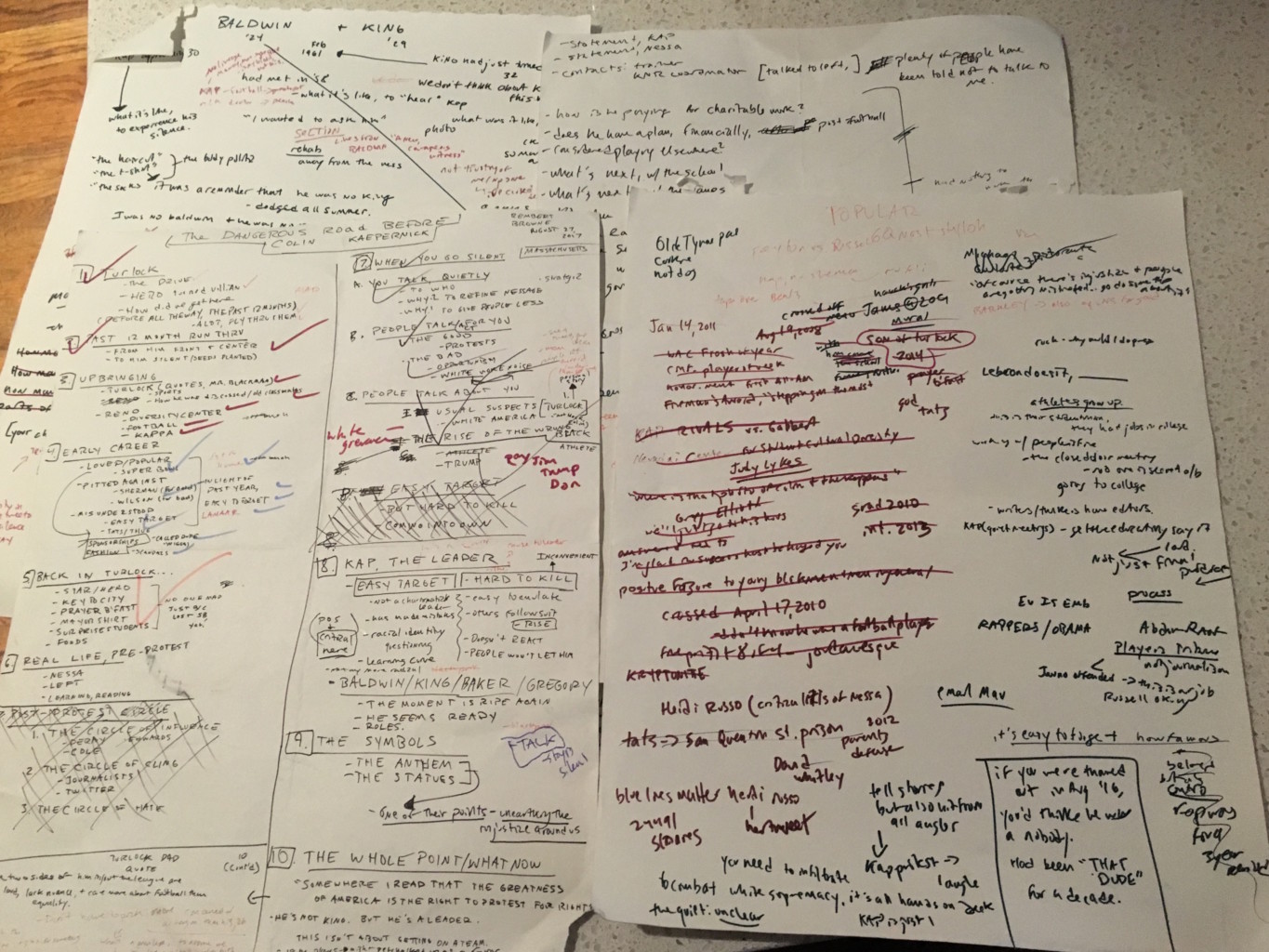

I spent a week and a half writing an outline. I had some themes I knew needed to go in there. It was basically like writing two pieces; there was the Kaepernick stuff, and the non-Kaepernick stuff.

Part of Browne’s outline.

I knew I wanted to start in Turlock. Then the transitions are always the hardest part, because how do you leave and come back? This idea of Colin’s silence ended up being the theme that could tie everything together. There was his silence to me, as in not talking to me, and then also his silence and the way people were using it to talk for him, to talk about him, to promote him, to tear him down.

Craft is a word with a lot of pressure, like you’re an artisan or whatever. The outline was 10 sections, and by the time I got through section two I already had 5,000 words, so I was like Oh, God.

My editor Matt [Sullivan], he’s so good. That Esquire, David Granger background, you can feel it. He would take it, go away for a while, come back, and say, “This is all good. Let’s squeeze it, tighten it.” He would take my outline and, while he was tightening stuff up and rearranging, I would dive into the next section and try to write it.

One thing I realized as the final days were happening, I still had only read the end of the piece like four times, but I had read the first 4,000 words of the piece 600 times.

I didn’t write the end of the piece until three days before it came out because I was in Green Bay. That was a very spontaneous decision, because I didn’t have [a key quote from Seattle Seahawks tight end and activist Michael Bennett]. I was just hoping he would say something to me and thank God he did. Sometimes things are just perfectly fortuitous.

At a certain point there were three editors working on it. It was surgical. The way I write, I have to start from the beginning. One thing I realized as the final days were happening, I still had only read the end of the piece like four times, but I had read the first 4,000 words of the piece 600 times.

I just love being edited by smart people. It was still my voice, but there were parts I loved writing, great lines, that I knew needed to get taken out. That’s fine; they were just filler. What this piece didn’t need was any filler; it needed every line to be meaningful.

I feel like I’ve lived eight careers online so far. I feel like I went to internet college at Grantland. So I was prepared to be at a place like New York magazine, but then I also learned new stuff there. Writing for print is a completely different universe. I used to feel super young, and now I feel like an old grizzled veteran. I’ve realized I care more about writing than I care about being a journalist forever.

I used to think I wanted to be like Ta-Nehisi. Now, I don’t know if I want to be working for a magazine forever. I hit a point a couple years ago where I was writing about all these people that I felt were peers, that were the same age as me and were making stuff. People like Issa [Rae] and Donald [Glover]. To put it plainly, I was just jealous.

I was envious and jealous of people who I consider geniuses, but also people who were doing things I think I could do, given the resources and time. And I just asked, At what point do I put myself in this lineage, or am I just going to be writing about them forever? A piece like the Kaepernick piece felt like I was contributing to a creative syllabus of sorts.

I felt like I was making something. This felt like an artistic, creative undertaking more than a piece on Colin Kaepernick. This felt like a critical essay.

I had never cared about words and language like this. One thing about writing something that’s 10,000 words long is you have to keep people there the whole time, the same way you have to keep people watching a movie all the way through. I had to think about this piece and do things to keep people there, because at any point someone could read any of the other million things you can read online. I’d always wanted to write something big like this, that almost felt theatric.

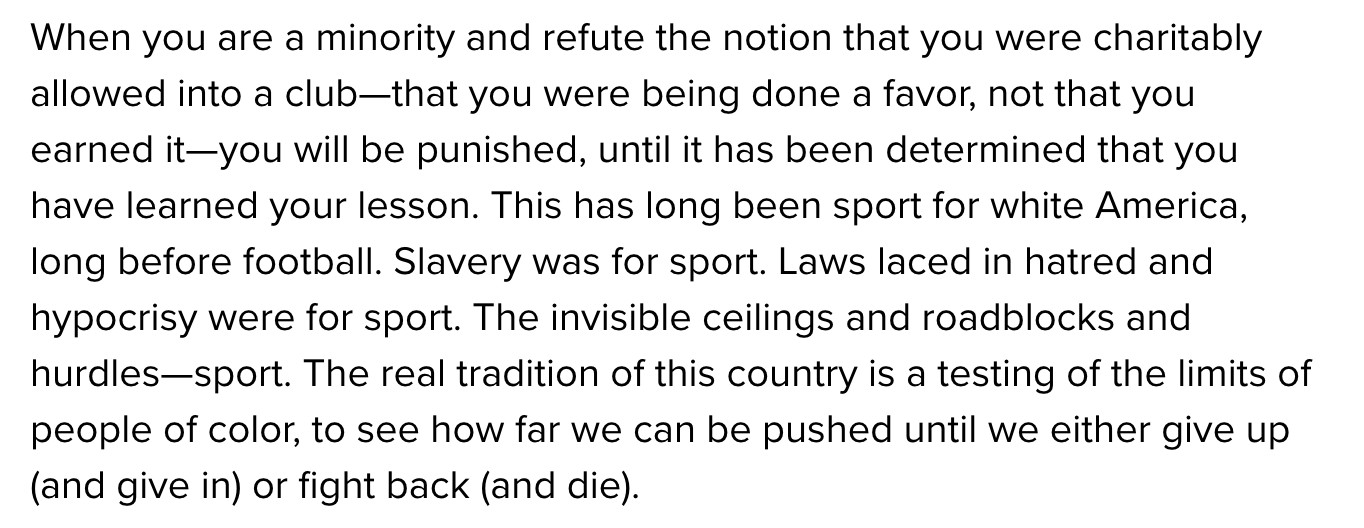

This is not stick-to-sports world. I started off with the idea that Kaepernick is a metaphor for so many things. So yeah, there are lots of things I write where I start off a little cautious that I ramp up or start out super raw that I dial back.

There’s a lot in there that is very personal. I felt that way at jobs I’ve had. Sometimes I wonder if I’m going too far. There are lots of parts in there that are not subtle, where I’m shooting from the hip. Sometimes I write stuff hoping that someone that’s made me or other people feel that will read it and internalize it.

That’s one reason writing about Kaepernick was so interesting, because there were lots of things about the way he was being talked about and treated that were very relatable for lots of people of color that work in a white newsroom, or any job. I always get nervous, but I feel like I have an obligation to say lines like that. It’s supposed to hit.

I was writing this with Trump’s America in the front of my mind and in my heart. The NFL, police violence: I felt all of that was coming out in my writing, whereas at times in the past I had tried to file that away so I could focus on the task at hand.

In this piece, I let it all come in and still did the task. It’s hard. It took me a lot longer to write this piece. There were full days when I couldn’t write anything, and that’s a hard thing to explain to editors. But there were days when I just didn’t have it.

It felt exposing. I felt super vulnerable. I had a very tumultuous year and I felt a lot of that came out in this piece. The people I know who read it, they were like, “You needed this.” I read the piece the morning before it came out and felt Yeah, this is it. I had never really felt like that before. It wasn’t like, Everyone’s going to fucking love this. It was like, We did this right. My mind is blown by how many people read 10,000 words.

It’s a privilege to have something to work on for five months that can almost pay your bills.

I think I’m finally OK with saying I have a unique perspective on things. My mom just made very smart parental decisions in terms of what I was exposed to.

Growing up in an all-black neighborhood and going to an all-black school, then at some point going to a white school but never leaving the black neighborhood. She spread me around and got me exposed to stuff early so I thought about my own upbringing when it came to someone like Colin’s upbringing.

I’m fascinated that someone like Kaepernick wants to be a black intellectual and a black leader, because he wasn’t built for it. I was built for it. I’m literally supposed to be doing this right now. My mother came up in the era of black radical psychologists in the ‘70s and ‘80s. I grew up around all the books. She raised me to be a highly contributing member of society, to my community, to black folk, a credit to my race, all that shit.

So I am justifying her private school dollars that she paid and her decision to surround me with black folk. I know that there’s no amount of education and there’s no amount of adult training that could get me to write this type of piece—this piece really comes out of ages 0 through 18. It comes from the kind of worlds that she put me in, and some of the worlds she didn’t put me in. Love her.

ICYMI: You might’ve seen the Times‘s Weinstein story. But did you miss the bombshell published days after?

before this piece comes out,

thank you martin

thank you nina

thank you james

thank you kara

thank you langston

thank you mom— Rembert Browne (@rembert) September 12, 2017

I have to take on big topics. I don’t think of it as having a choice in the matter. I’m very privileged to have gotten a better start than most other people. Most writers don’t get edited crazy hard in their early 20s. It’s not an accident. It’s a privilege to have something to work on for five months that can almost pay your bills.

I look around and it excites me to see young writers of color who I know came up reading me and some of my peers—Jamelle Bouie, Adam Serwer, Jason Parham, Jenna Wortham—folks like that who are in their early 30s now. Five or six years ago, there was one of us at each place, and we all kind of got to know each other.

A lot of my peers have transitioned out of writing, and they’re either primarily on the editorial side or doing awesome stuff in different areas. So I also feel a responsibility—not just by being 30 and being young and being black and all that—but my main focus is still writing. More than podcasting or doing videos, writing is still my No. 1 priority, which, with each passing year, becomes less and less of a thing that people do.

I don’t want to die on this hill, but not a lot of people can take these swings, so if you have the privilege, if you’re in a position to take the swings, sometimes you look around and are like, Well, who else is gonna take them? I might as well be one of those people.

I wanted to do the subject matter justice. There are already parts of this piece I would improve upon. It’s not a perfect piece; it’s arguably half a section too long. It’s just like, This is the piece I was supposed to write at age 30 in the summer of 2017. That’s how I think about it.

ICYMI: “I spent 45 minutes on the phone with Megyn Kelly asking her to not run that show”

Pete Vernon is a former CJR staff writer. Follow him on Twitter @ByPeteVernon.