Jake Fisher knows what a difference a thorough test can make. About five years ago, near the end of 2012, his two young sons wanted to play with a Lexus ES 350 parked in their driveway. Specifically, they wanted to be locked in the trunk. The 9-year-old rationalized to his dad, “What if I ever get locked in? I want to be able to make sure I know how to [escape].” The child clambered inside, pulled the emergency trunk release, and had no problem getting out. Then the younger child got in. Silence. Suddenly, Fisher hears boom-boom-boom: the sound of 4-year-old Alexander hitting the door. “Dad! Dad!”

“I open up the trunk and he’s sitting there with the handle broken off in his hand,” Fisher tells CJR. “He went to use the emergency latch and it had snapped right off and didn’t let him out.”

Fisher was in the process of testing the Lexus for Consumer Reports, where he is director of auto testing, which is why the luxury sedan was stationed in his driveway that winter afternoon shortly after he had picked up the kids from school. After the incident involving Fisher’s son, the magazine discovered that handle was on approximately 700,000 Lexus vehicles. Parent company Toyota and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration were notified, and a customer service campaign was announced for replacement latches the following month. The finding was “not a regular part of our test program,” CR said in a report—it was Fisher’s years of experience and the extra time given him to test the Lexus at home that allowed for the catch.

ICYMI: Looking for a journalism job? Here’s what hiring managers at WashPo, NPR and others

Such findings are why millions of people subscribe to Consumer Reports, making it one of the most popular magazine titles in America. In an era of budget cuts, pivots to video, and quick aggregation, Consumer Reports is unusual in the American media industry for its nonprofit subscription business model, massive resources, and dedication to original reporting and research. “We have always been independent,” President and CEO Marta Tellado says. “We are nonpartisan. And we’ve never taken a single advertising dollar. We’re a very unique organization.”

Yet income at the company is down, subscriptions are falling, and the 83-year-old magazine faces an ever-growing assortment of advertising-driven and online-only competitors, including Wirecutter, a site owned by The New York Times that is now publishing product reviews. In this new era, can CR hang on to the top spot in consumer reporting?

CR and its parent organization, Consumers Union, began in February 1936, after a group of striking employees at its predecessor, Consumers’ Research, were frustrated with working conditions. Consumers’ Research still exists, along with a seasonal magazine, but it stopped doing lab work in 1983 and its revenues are significantly smaller than the organization that rose in its opposition.

More than 81 years after the first edition of the magazine (then titled Consumers Union Reports) was published in May 1936, CR still produces 12 print issues a year, including one focused exclusively on cars, as well as an annual buying guide. In 2017, CR had 3.6 million print subscribers (more than People), who pay $30 a year, and 2.9 million online subscribers. Its online traffic grew to an average of 14 million monthly uniques in 2017, up 17 percent from the previous year, according to a company spokesperson.

The modern mission of Consumer Reports (which rebranded with a new CR logo in September 2016) is a “fairer, safer, and healthier world” through its research, media, and advocacy. In addition to testing products, CR reports on larger issues like discrimination in the car insurance industry, food recalls, scams afters natural disasters, net neutrality, and the Equifax data breach. Advocacy work is done by Consumers Union, the policy and action arm of CR. All while CR continues to undergo a multi-year strategy focused on attracting younger readers, primarily through its digital content both in and out of its paywall.

To stay independent, CR purchases all of its test products at retail, resulting in enormous costs. During CR’s fiscal 2016, which ended May 31, 2017, the magazine spent $2.1 million on cars and $1.5 million on “other items,” a category that spans the wide girth of American consumerism and includes such disparate products as treadmills, mattresses, bacon, and breast pumps. That’s in addition to the salaries paid to more than 550 staff—comprised of engineers, statisticians, mechanics, lawyers, and its editorial team—plus the operating costs of the company’s 50 testing labs, its 327-acre auto test center, three other offices, fundraising, lobbying, and, of course, its own advertising. In its most recent financial statements, CR reported expenses totaling just under $247.2 million for the fiscal year and revenues of more than $241.7 million.

Consumer Reports President and CEO Marta Tellado at her office in Yonkers, NY. Photo by Karen K. Ho

While the growth of CR’s readership is impressive considering the layoffs and budget cuts across the media industry, the company nevertheless hasn’t escaped turmoil. At the end of 2008, CR purchased Consumerist.com from Gawker Media, in a bid to attract younger readers who might eventually switch to a paid subscription. But last October, CR shut down Consumerist.com, folding it in to the mothership.

The closure followed a wrenching period for CR, including losses in 2010 and 2011. The organization went through an extensive restructuring, which included several high-profile layoffs and a 13 percent reduction in staff during 2012 and 2013. CR’s financial statements show revenue from subscriptions, newsstands, and other sales has steadily fallen from $234.2 million in the fiscal year ending on May 31, 2013, to just under $205.5 million in 2017, a decline of more than 13 percent. Operating income also fell significantly, from $8.2 million in 2015 to a loss of $5.9 million in 2016. The next year was slightly better, but CR’s operations were still in the red with a loss of $5.4 million.

When asked about these numbers, Chief Financial Officer Eric Wayne says the organization’s financial reserves, or total unrestricted net assets of $167 million as of May 31, 2017, are growing and at a high enough level to absorb such a significant operating loss over the past two years. He notes that investments in IT infrastructure, branding, audience strategy, a new numeric ratings scale, another redesign, and buyouts have contributed to the operating losses.

Meantime, subscriptions are falling. In 2007, CR had more than 8.5 million subscribers across five titles. By May 31, 2017, CR’s subscription numbers had fallen even more to 3.6 million print and 2.9 million online, a three-year decline of more than one million subscriptions and a drop of more than $31.8 million in subscription revenues between June 1, 2014 and May 31, 2017.

When the new [executives] came in, they began basically ignoring us and our way of doing things. So they didn’t give us a chance to come up with our own ideas. They thought they knew what was best.

As CR transitioned to a new leadership team, approximately three dozen senior staff were let go, were forced to leave, or willingly left between 2012 and 2015. Many had worked at the organization for more than 15 years.

Former Technology Editor Jeff Fox is one of them. He started at CR in 1990 and stayed for 24 years, but he says things shifted during the recession in 2008, along with the introduction of digital tablets and the rise of mobile. Fox says many CR staff always considered the organization to be less vulnerable to economic downturns due to the absence of advertising. “The belief was we could adapt better than anyone else could,” he says. “This time it was different. The old-fashioned media people didn’t get [tablets]. They were completely ill-prepared for smartphones.”

During the last few years Fox was at the company, he says the senior editorial staff was aware of how subscriptions were falling and change was needed, but they were the ones being “methodically” gutted—including fact-checkers and copy-editors.

“We were all nervous, we knew we had to change, we knew we might go out of business, but we were flexible and we didn’t want to go without a fight. But the managers didn’t give us a chance,” he tells CJR. “When the new [executives] came in, they began basically ignoring us and our way of doing things. So they didn’t give us a chance to come up with our own ideas. They thought they knew what was best.”

When asked about these comments, Tellado wrote in a statement, “Change was required, and everyone at CR was brought in to determine our way forward.” She also cited a recent staff survey conducted last month, in which “97 percent of employees said they were proud to be associated with CR.”

Kim Kleman worked for CR in a variety of editorial roles for 16 years, including almost seven as the editor in chief of the magazine, until she left in June 2013. Her successor, Ellen Kampinsky, was named to the position in April 2014 and then replaced by Diane Salvatore only 13 months later.

“It was just Nirvana as a journalist that you didn’t have to worry about ads and all this stuff,” says Kleman, who has also been an adjunct associate professor at the Columbia Journalism School, which publishes CJR, since January 2010. “They just have resources that nobody else has, and you just want them to be the biggest and best thing that they can.”

Even the manufacturers are interested in the data, because they can’t even afford to compare themselves to 20 other models.

Another ongoing challenge is the older demographic of much of CR’s readership. In 2008, the average age of a CR print subscriber was 60, and that of the average online subscriber 50. By 2016, those ages had risen to 65 and 56, respectively. (Part of CR’s revenue includes a planned giving department, which encourages readers of the print magazine to remember the organization in their wills through bequests and gifts of assets.)

CR’s aging audience is a particular problem because younger people don’t have the built-in allegiance to professional reviews, preferring online opinions.

CR has also been affected by the increasing scrutiny on consumer data and personal privacy after it settled a lawsuit in Michigan for $16.4 million on April 9. Reuters reports CR’s parent company, Consumers Union, was accused of selling information from magazine subscribers, such as their histories and reading habits, “to data-mining companies and others in exchange for demographic and lifestyle data, and then selling ‘enhanced’ customer profiles containing this data to other companies for a profit.”

ICYMI: 11 images that show how the Trump administration is failing at photography

Insurers will cover the full amount of the settlement, and Consumers Union denied wrongdoing, saying in court papers the company settled to avoid “further expense, inconvenience, and burden.”

In a written statement, a spokesperson for the company says, “CR was one of many media organizations sued in the same manner, over the same Michigan law. While we believe that our practices were in compliance with Michigan law, we chose to settle this case, without admitting liability, so that we can spend our time, effort and resources on protecting consumers and not on additional legal fees and the uncertainty of litigation.”

At CR’s Auto Test Center located five miles from the town of Colchester, Connecticut, dozens of cars are tested around-the-clock, from inexpensive subcompacts to high-end luxury sports cars like the Porsche 911 Carrera S or the Mercedes Benz S550, along with car seats and tires. I toured several buildings centered around a former drag-racing track, each designed to assess a vehicle’s performance in different weather conditions, emergency scenarios, and terrain. Staff also drive the vehicles for months at a time, commuting to work, taking them on vacations, even going to the grocery store.

If you put a block of Styrofoam out on the track, [the cars are] not going to stop. It has to have tires and a license plate. It has to physically look like a car. We’re constantly having to make up stuff to evaluate some feature a car didn’t have yesterday.

On a cloudy, rainy day in early January, Fisher, CR’s director of auto testing, along with Jennifer Stockburger, director of operations, and two spokespeople, showed me around areas focused on testing headlights, maneuverability, and luggage capacity. There’s even a foam “puzzle” car, which resembles a white Prius, used to test radar, LIDAR, and camera-based safety systems. The stand-in is purposely designed to trick and trigger some of the technology features in new vehicles. “If you put a block of Styrofoam out on the track,” Stockburger says, “[The cars are] not going to stop. It has to have tires and a license plate. It has to physically look like a car. We’re constantly having to make up stuff to evaluate some feature a car didn’t have yesterday.” The cost of the custom-made prop: approximately $35,000.

Deceptive appearances: The foam Toyota Prius used for testing safety features at Consumer Reports’ Auto Testing Center. Photo by Karen K. Ho

During a drive in a Tesla Model X 90D, Fisher points out white-and-yellow lane markings freshly painted on a stretch of pavement, used to assess technology features in newer cars like lane departure warnings, lane centering assist, and adaptive cruise control. “It’s the closest thing you have to autonomous driving,” he says. He demonstrates by speeding up to 55 miles per hour while on autopilot and taking his hands off the wheel. “I just noticed this car lacks sufficient [interior grab] handles,” a spokesperson says from the backseat. “Oh shoot! handles,” Fisher replies with a grin.

Tire testing is one of the most cost- and labor-intensive long-term projects at CR, with 50 to 70 models each going through 14 tests for performance assessments in areas like snow traction, ice breaking, ride comfort, and treadwear over the course of a year. “It’s expensive, so even the manufacturers are interested in the data, because they can’t even afford to compare themselves to 20 other models,” says Stockburger. In a building where dozens of the black rubber wheels are stored, Stockburger estimates the tire testing budget alone is approximately $500,000 per year, with car seat testing coming in between $300,000 and $400,000 annually.

In the labs at CR headquarters in Yonkers, New York, the testing methods require just as much attention to detail. Every vacuum cleaner is measured by how well it sucks up Maine coon cat hair on the same persimmon orange carpet. Snowblowers are tested before winter using carefully arranged piles of wet sawdust. The laundry lab has been using the same pig-blood-stained swatches and hole-punched fabric squares to test cleaning and agitation levels for decades.

Jake Fisher, director of Auto Testing, and Jennifer Stockburger, director of operations, at Consumer Reports’ Auto Testing Center in Colchester, Connecticut. Photo by Karen K. Ho

Even if you’ve never subscribed to CR, you’ve likely read or heard about its results in the press or on programs like Good Morning America. CR produces its own multimedia content, including podcasts and 360-degree video, for a network of 150 local broadcast and Telemundo stations. This digital content is then published or syndicated on its website, Amazon, Apple TV, MSN.com’s auto vertical, and on its YouTube channel.

The only place you won’t find CR is in ads. Unlike the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS), Consumers Digest, and Car and Driver, CR has had a longstanding policy of not allowing its ratings or reviews to be used in any advertisements, going so far as to sue when it does happen. When CR staff spot violations of this rule in small businesses, like a cable provider in Macungie, Pennsylvania, with a sign declaring “#1 cable by Consumer Reports,” they issue cease-and-desist letters.

Stockburger points out that car manufacturers often pay a lot in licensing fees to mention some of these awards, and The Wall Street Journal reports those fees can go as high as $300,000. I ask Fisher, Stockburger, and two spokespeople if CR has ever considered changing this policy. The group acknowledge lifting this rule would provide a lot of free advertising and increased awareness of CR’s brand, like when a vehicle is promoted as “Motor Trend Car of the Year,” or as an award winner by J.D. Power and Associates during the Superbowl. “I would say we’re never ignorant to that fact,” says a spokesperson. “It’s always in conversation. If we could ever do it in a way where we felt it wouldn’t jeopardize or conflict with our mission and our core values, we would take that option.”

“We’d be fools not to think about it,” Stockburger says.

Instead, CR has scripted its own messaging. In late May, CR launched a new digital advertising campaign with a video called “Let’s Keep It Honest.” It emphasizes CR’s history, reviews, and advocacy work on issues like seatbelts. The company filed for a federal trademark of the phrase at the end of January and plans to run the advertisements across a variety of sites, including the HuffPost, Hulu, Essence, Babble, Blavity, Univision, and HGTV.

The consumer-first mission of CR also means the organization’s first instinct after finding any serious faults or deficiencies in products is to approach companies or manufacturers for a response or fixes before publishing a report, like when Fisher discovered the faulty Lexus latch. “If you were to go and broadcast to the world, ‘Look, this car is unsafe,’ sometimes a manufacturer might go into a very defensive posture,” Fisher says. “And that doesn’t really help anyone.”

Chief Content Officer Gwendolyn Bounds says this action-oriented approach is often a recruiting draw when she’s hiring for her department. “If you get into this business because you want to make change in the world, and many journalists start out doing that, this is a pretty compelling place to come to do it.”

The problem for CR now is that The New York Times, a company already known for its journalistic chops, has taken direct aim at the publisher, becoming its most daunting competitor.

The consumer reviews website Wirecutter was created by Brian Lam in September 2011. Initially, it existed as a bootstrapped appendage of The Awl blog network, focused on well-written technology reviews. It had no outside investment and generated revenue only through referral links to companies like Amazon, which gave Wirecutter a small cut of each completed sale (approximately 4 to 8 percent).

It turns out a lot of consumers are interested in the “best” item “for most people” through “reviews for the real world” that are less focused on lab results and benchmarks. In June 2016, Recode described Wirecutter as a “sort of modern update to Consumer Reports.” After generating impressive annual sales for a relatively small amount of content, the startup was acquired by the Times for $30 million.

Wirecutter has now grown to more than 100 remote and in-house staff who test, research, and review a wide variety of items, sort through thousands of deals, and regularly update past reviews.

One of the best-known examples is the company’s guide to bike locks, which involved consulting professional thieves and then destroying the top contenders using an array of power tools.

Wirecutter doesn’t hide the fact that many of its reviews draw upon the work of other sites like Reviewed.com, CNET, America’s Test Kitchen, and Consumer Reports, as well as user-generated reviews on sites like Amazon. “We’re not afraid to cite them, because then we don’t have to pretend they don’t exist,” says Nathan Edwards, senior editor for computers, networking, and pets. “I don’t think people just come to us. I think they go to 20 different tabs and read them all.”

Wirecutter differs from CR in that it tests a select number of items (many of which are loaners or freebies) rather than most of what’s on the market, explicitly recommends a top pick “for most people,” and details at length how that decision was made, including references to any existing research and reviews. Not every category includes original testing, but when it does, Editor in Chief Jacqui Cheng says the process is focused and centered around the actual user experience rather than lab results or industry benchmarks for performance. One of the best-known examples is the company’s guide to bike locks, which involved consulting professional thieves and then destroying the top contenders using an array of power tools.

“We are really evaluating stuff, in general, from a usability standpoint,” Cheng says.

Wirecutter Editor in Chief Jacqui Cheng at the offices of the New York Times. Photo by Karen K. Ho

Wirecutter also produces reviews for a much wider range of categories than CR, including products such as menstrual cups, electric skateboards, beginner bass guitars, tricycles, and “weed grinders.” Sometimes a review will say nothing on the market is worth buying. “If I run into something in my personal life, there have also been times we turned that into a guide, like with fireproof safes,” says Senior Staff Writer Nick Guy, who was inspired to research the item for Wirecutter after remembering when he received one from his parents as a Christmas gift a few years prior. “It was too small, though, so I went to Target looking for a model large enough to hold hanging file folders. I had no idea which model to choose or why.”

Guy’s father and grandfather had experience in the fire service and were willing to help him build and burn down a small room as part of the testing process.

Wirecutter is upfront about why it doesn’t evaluate dozens of items in each category, and that many of the tested items are loaners or freebies from vendors, or press and marketing departments. “Sometimes you can ask the experts and get the best answer from them and use their cumulative decades of knowledge to answer the question, ‘What should I get?’” says Strategy Editor Ganda Suthivarakom. “We don’t always test for testing’s sake.”

Prior to Wirecutter, both Cheng and Lam spent many years working in tech journalism, a segment of the media industry in which supplied test units are standard practice. “It does keep costs low,” Cheng says. “But it depends on the category, too. And we do have very strict ethics policies about how no one can keep anything, even if we buy it, unless it’s for long-term testing.” Cheng says there have been moments when Wirecutter staff have purchased a product at retail out of extra concern a review unit would not provide the same experience as a product off the shelf.

Executive Editor Michael Berk says in some categories, like pets and kitchen, there is much more retail purchasing. (For its review on infant car seats, Wirecutter purchased and home-tested seven, then crashed-tested four in a lab, including for side and front impact. It’s currently in the process of testing larger child seats. By comparison, CR assessed 32 infant car seats, along with 84 in four other categories.)

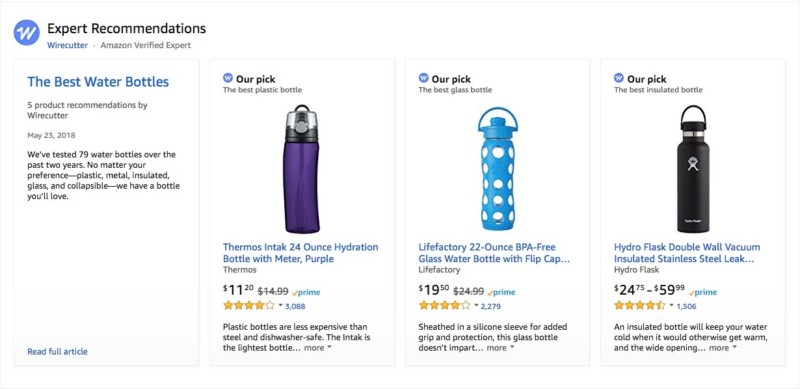

The consumer review website’s growing influence—it has been regularly featured in the Times’s Smarter Living section and on Good Morning America—includes a new, larger partnership with Amazon beyond its affiliate relationship. The company is now designated a “Verified Expert” by the e-commerce giant, which features top picks and some of Wirecutter’s articles and reviews directly on Amazon’s website for select keywords.

A search for water bottles on Amazon.com brings up Wirecutter reviews and its top picks.

A few days after Wirecutter was acquired by the Times, then–Public Editor (and former CJR Editor in Chief) Liz Spayd wrote about readers’ letters to her, expressing concern about the connection between the recommendations, the Amazon commissions earned from any sales, and the possibilities for conflicts of interest. “I hope The Times will move cautiously, not merely assuming readers will view this as a useful new service but actually asking them whether they do. The Times has a lot to gain. And also to lose.”

While Wirecutter is ranked lower than CR in terms of US Web traffic by Alexa (770 compared to CR’s 583 as of press time), the digital-only site’s readership is also significantly younger. According to a New York Times spokesperson, in the past 14 months, Wirecutter’s largest age group ranged from 25 to 34, and its average user from age 41 to 53.

The New York Times Company’s report on its 2018 first quarter, released on May 3, also noted the site’s financial success, stating, “Other revenues rose 5.0 percent in the first quarter [to $27.7 million] largely due to affiliate referral revenue associated with the product review and recommendation website, Wirecutter.” Wirecutter President David Perpich notes the company does earn some revenue from banner advertising, but it is currently less than 10 percent.

Wirecutter President and General Manager David Perpich at the head offices of the New York Times. Photo by Karen K. Ho

A restructuring in March also led to the elimination of much of Wirecutter’s outdoors coverage and layoffs of its outdoors team. “We are re-focusing our coverage areas to emphasize home products as part of an effort to best serve our core audience,” a spokesperson told CJR via email. The total number of laid-off staff was not disclosed.

In an interview, Cheng pays respect to CR and Reviews.com, and says she views Wirecutter’s work as a different kind of service. “We don’t want to redo tests that others have done, but also we want to do tests that are going to be contextual for the reader, something that’s actually useful to people,” she says. “A lot of times when we are reading other people’s research, it just feels almost like everything is just broken down into benchmarks and lab results.”

(When asked about Wirecutter’s shortcomings, Tellado writes, “In a sea of unaccountable review sites and user comments, CR offers something unique: independent, nonprofit insights that equip people to shape the marketplace and navigate day-to-day purchase decisions. Because we buy every product we rate and don’t sell ads, people know that we serve one constituency and one constituency alone: consumers themselves.”)

With no shortage of media in addition to Wirecutter now publishing product reviews, CR is devoting many of its resources to attracting a younger crowd, including a targeted ad campaign, a bundled subscription, and an auto show on YouTube. “We’re investing so much in reporting on the roots and the cause of the education debt issue, championing net neutrality,” Tellado says, “and we’re also giving them guidance and helping that age cohort when something like the Equifax breach happens. It’s a very uncertain environment. That really underpins and underscores the strategy.”

A major part of CR’s effort to distinguish itself is the new membership platform provided as part of its All Access subscription, which bundles print and online for $55 per year. One of the additional features is Ask CR, an online, one-on-one chat advisory and recommendation service staffed with CR specialists that was beta-tested in the fall.

CR is hoping to move away from external platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat, while also helping members customize information to their interests and enabling actions based on what customers have read. “For us, building community is a very powerful proposition because of the breadth of what we do,” says Bounds. “Product reviews might be all [readers] want, but we also might have someone who reads a piece of our investigative journalism on car insurance pricing and how it’s unfair in certain markets. [If] they’re upset and then within our platform we can give them a lever, to click here to send a letter, we channel that passion.”

Consumer Reports Chief Content Officer Gwendolyn Bounds in her office in Yonkers, NY. Photo by Karen K. Ho

Stockburger believes the future of CR will be with younger fans of projects like Talking Cars, the auto testing center’s weekly video and podcast series. “It’s very different than who reads the Consumer Reports [print] magazine,” she says. “Car enthusiasts and young men are the highest demographic.”

Much has changed culturally since CR’s first issue, including the rise of fake reviews on Amazon, but Bounds points out there is a long history of companies trying to outsmart the general public. “When we were founded 80 years ago, there was another world order of disinformation and fake news coming out of manufacturers who were putting out products and making claims that were false,” she says. “There’s real value in user reviews online, but I think sometimes the systems can be gamed. There is a reason for Consumer Reports to exist now as much as when it was first founded.”

As a nonprofit, Tellado is conscious of the importance of revenue, but to her, success at CR is still defined by its impact. “The power that we have needs to be felt and heard,” she says. “And that power, we’ve seen time and again, through the work that we do, has the potential to actually shape the marketplace. At the end of the day, that is our bottom line—making a difference in consumers’ lives.”

Update: This piece has been updated to clarify that CR’s print subscription numbers, not its subscription price, were greater than People‘s in 2017, according to the Alliance of Audited Media.

ICYMI: Two dozen freelance journalists told CJR the best outlets to pitch

Karen K. Ho is a freelance business, culture and media reporter, based in New York. She is also a former Delacorte Fellow at CJR. Follow her on Twitter @karenkho.