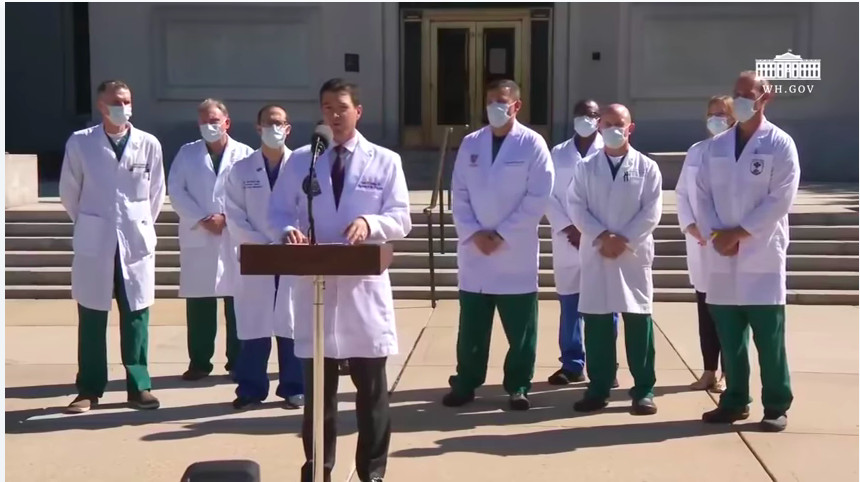

On October 2, just after midnight, President Donald Trump told the world that he and First Lady Melania Trump had contracted COVID-19. Immediately, a fog of nonsense official information emanated from his team.

On October 4, the President’s physician, Sean Conley, described Trump’s oxygen saturation—a key measure of how much oxygen the blood is carrying—thus: “It was below 94 percent. It wasn’t down in the low 80s or anything.”

That is essentially meaningless. The distance between those two figures ranges from moderate symptoms to catastrophic illness. As a New York City ER doctor, I’ve cared for young and healthy patients who suddenly become critically ill, and elderly ones who rebound unexpectedly.

What followed was even more disconcerting—to me as well as to others on the front lines. Into the information vacuum have poured countless talking head doctors, in every media outlet. Their commentary has ranged from explanatory to speculative to maybe misleading; sometimes, they offer a prognosis for a patient they have never met.

It’s understandable, on one level. The public needs to know the health status of elected officials. Experts contribute crucial background when discussing complicated cases or new therapies.

But it remains impossible to assess the clinical condition of a patient you don’t know, and irresponsible to do so.

Robert Wachter, chairman of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, has been a cable-news mainstay throughout the pandemic. On October 7, he appeared on CBS, TMZ, CNN, and MSNBC. He offered sound analysis but also repeatedly stipulated that, based on risk factors, Trump had between a one-in-five and a one-in-twenty chance of dying, depending which appearance you watched. His willingness to throw around these numbers, and to speculate on the effects of the steroid dexamethasone on the President, likely made him a popular guest.

I get casual requests all the time—but I’d be loath to tell a friend at a cocktail party that their aunt had a ten-percent chance of dying based on her age and symptoms alone, or to suggest that they were experiencing psychosis because of a steroid. COVID-19 makes such a prognostication even more fraught than usual. So do the toxic politics of the situation.

On October 3, Fox News commentators Drs. Marty Makary and Marc Siegel reassured viewers that Trump’s move to the hospital was preemptive. “A lot of this is precautionary monitoring,” Makary said. “There’s probably a one-in-a-hundred chance that he’s going to need something urgent.” Plus, he added, “he’s not going to be in a hospital bed with a curtain and a roommate; he’s going to be in a luxury suite.”

This does not cover anyone in glory. So let’s not enter the fray at all. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association developed the Goldwater Rule, in reaction to a 1964 magazine survey in which psychiatrists assessed Barry Goldwater’s state of mind. (One characterized Goldwater as “basically a paranoid schizophrenic who decompensates from time to time.”) The rule states that it is “unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization.”

The Goldwater rule has been skirted occasionally since then; a 2017 letter, signed by 35 psychiatrists, suggested that Trump exhibited “a profound inability to empathize.” But it has generally been respected. A similar code might provide guidance to clinicians who feel compelled to prognosticate on a celebrity’s condition based on incomplete information or political motivation.

I’d rather we attempted to counter misinformation—about the virus, about public health, and about vaccines—while pressing for transparency regarding the health of civilian and military leaders who have been unnecessarily infected. We should be encouraged by the media to advocate fiercely for science-driven policy and smart public health measures. Likewise, journalists will discover the richest stories when asking tough questions about those subjects, with a focus on what comes next for all of us, rather than just a privileged few.

Christopher Tedeschi is an associate professor of emergency medicine at Columbia University.