Print and online readers of a heart-wrenching true story display equal empathy and emotional engagement, regardless of the medium in which they read, according to a study conducted by the Columbia Journalism Review and the George T. Delacorte Center for Magazine Journalism.

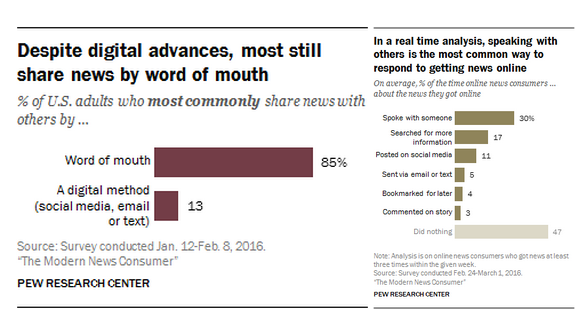

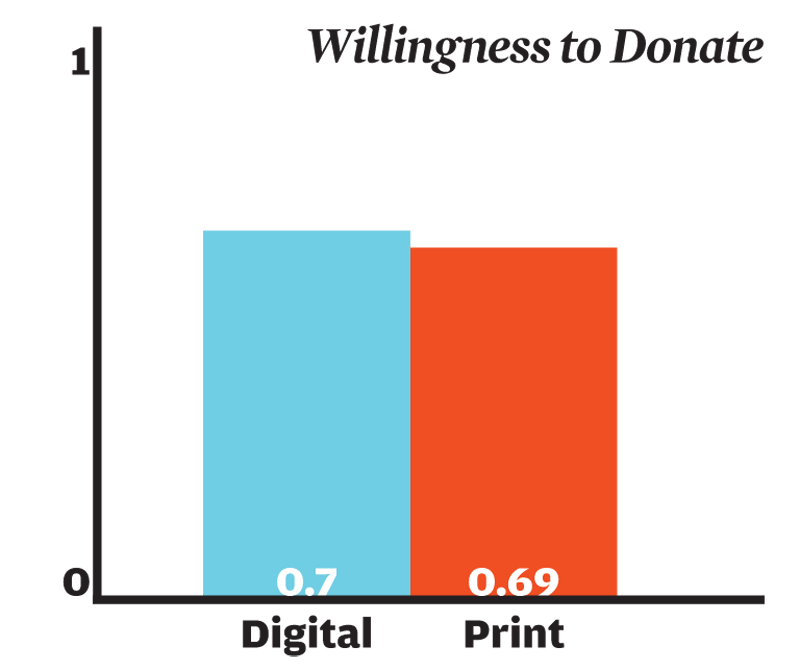

The study compared the emotional responses of a group of people reading a magazine feature in print with those who read the same story on a screen. On practically all measurable levels, the two groups yielded surprisingly similar results: Print and digital readers remembered the same level of detail. They felt equally engaged in individual parts of the narrative, and in the story overall, and were similarly likely to act on their emotional responses by donating money or time to a cause associated with the story.

Related studies have also found no difference in comprehension in back-to-back comparisons between print and digital. But those results seem to contradict a consensus among scholars who say there are fundamental differences between reading experiences on paper and on screens. When we read on screens, we skim, scan, get easily distracted, and create no memory of the information’s physical presentation, as we would with printed paper, according to researchers such as Anne Mangen and Maryanne Wolf. As a result, comprehension and retention suffer.

Our increasing intimacy with screens could have far-reaching implications for the way we read, understand, and remember written texts, some experts have suggested. It might even affect the way stories can move us to feel empathy for their protagonists and other characters, because empathy takes time and focus to develop. It’s a scenario with potentially significant consequences for journalism, which so often relies on readers’ empathy as a vehicle for generating social awareness and change, as CJR reported in the first half of this research project about empathy and journalism.

But when our study tested that hypothesis, the results did not support it. So have we proven that there are no differences at all between reading in print and on screens? Hardly, but the study results do illuminate bigger questions about how we interact with our digital devices: the real differences between paper and screens likely lie in the cultures we have built around them.

The real differences between paper and screens likely lie in the cultures we have built around them.

Study design

In collaboration with psychologist and cognitive neuroscientist Jenna Reinen, we developed an experiment in which 64 study subjects read the same magazine story either in print or online. To test if their emotional responses to the story differed, all subjects were then asked to fill out a computerized questionnaire that focused on their thoughts and feelings about the article, but also on general social interaction and empathic responses to real-life situations.

The subjects, who were found by advertising on the Columbia University campus, in the surrounding neighborhood, and on Craigslist, were randomly assigned to read in print or digital. Both groups had, on average, a college-level education, and a high level of digital proficiency. Subjects ranged from 18 to 60 years old, with an average age of 35 for digital readers and 31 for print readers.

Study subjects read “The boy with half a brain” by Michael Rubino, published in August 2014 in the general interest magazine Indianapolis Monthly. It tells the story of Jeff and Tiernae Buttars, who struggle with whether to submit their son, born with the brain abnormality cortical dysplasia, to radical surgery that will remove part of his brain.

Study subjects’ baseline empathy levels (difference not statistically significant)

The story was selected based on several criteria: We wanted a magazine article of at least a few thousand words to give subjects a substantial reading experience since time and empathy are known to be connected. “The boy with half a brain” is over 4,600 words, on average a 20- to 30-minute read, and had the added advantage of not having appeared in a national publication, making it less likely that subjects in New York would already know the story. We also wanted a story that was likely to resonate emotionally with as many readers as possible, so we looked for one that was not fraught with political or ideological tension.

The story opens in a small pre-surgical room, where Jeff Buttars is trying to focus on his own breathing while his 11-month old son, William, is being prepped for brain surgery. Shortly after birth, William had started suffering from daily seizures and spasms that only got worse and prevented him from developing normally, until doctors presented his parents with a choice. Without surgical intervention, they had a 2 percent chance of controlling William’s seizures, which otherwise would likely disable him, making him unable to feed himself or recognize his parents as he grew older. The alternative: a surgical procedure called a hemispherectomy, which would remove half of William’s brain in exchange for a 60 percent chance of ending the seizures; William would also lose a portion of his sight, use of his left hand, and possibly the ability to walk. After months of weighing their options, Jeff and Tiernae handed their baby over to a medical team that had performed many successful hemispherectomies, but had also lost patients, in a surgery room equipped with a high-speed drill and fish hooks. “I’ve just sentenced my child to die,” Tiernae Buttars thought.

But William survives the surgery, and develops better than feared. At nine, he walks, talks, plays sports and video games, and, despite a lower-than-average IQ, goes to school. His parents still suffer from guilt over their decision to let William undergo the surgery, though. “One day I might be able to say this was a really good thing for our family,” Jeff says. “I’ll never say it was a good thing for William though. Never.”

Study subjects’ memory of details in the narrative

An engaging, personal story, “The boy with half a brain” presents a dilemma, which we hoped would invite readers to step into the characters’ experience. While the theme of coping with illness and choosing to trust experimental surgery seemed uncontroversial, the family in the story relied heavily on faith and prayers in their time of crisis. Research shows that we are more likely to feel empathy for someone to whom we believe we are similar; non-religious participants, or participants who did not share the Buttars’ faith, may have been less moved by the story.

Our goal was, to the greatest degree possible, to simulate a natural reading situation. One half of the study subjects read the story in a print issue of Indianapolis Monthly, while the other half read the online version, either on a laptop or a stationary computer. The online version included a video, but for the sake of controlling the length and intensity of the reading experience, we disabled the internet access, and subjects were unable to watch the video or click on links. This choice had obvious disadvantages in terms of simulating an authentic reading situation, but it had other merits, as it allowed us to control how much time subjects spent with the story. On the questionnaire however, we asked subjects if they had tried to click on the video or on links in the story, while print readers were asked if they flipped through the magazine and looked at or read other stories. Few members of either group admitted to browsing.

The results

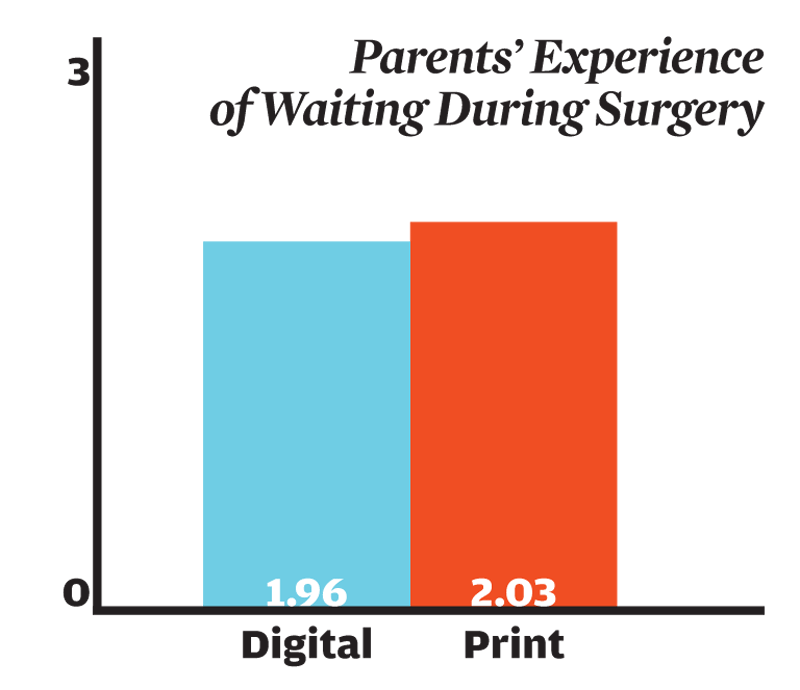

Some of the questions were designed to simply test how many details the subjects remembered (“What was the rationale for performing surgery on William?” and “What are some things William reports enjoying about life?”). Other questions aimed to test subjects’ feelings while reading the story (“How would you describe your emotional response to the portion of the narrative when the parents were waiting for the outcome of William’s surgery?” or “Hypothetically, if you were asked right now to volunteer for a charity that raises research funds for childhood cortical dysplasia, would you choose to participate on a one-time basis?”)

To gauge how much study subjects empathized with William’s parents’ quandary, and were able to relate that experience to their own lives, the questionnaire also asked if subjects imagined they would have made the same decision as Jeff and Tiernae Buttars in similar circumstances. Many of the responses showed that the narrative resonated with readers, and had them actively imagining themselves inside the story:

I“I really cannot predict what choice I would make,” one subject wrote. “I am very conflicted as to what is the better choice. Letting ‘nature’ take its course or intervening with the surgical procedure William had undergone seem equally horrible.”

Said another subject of William’s parents: “I don’t think I would have been as brave as them.”

As expected, the results showed that readers who remembered many details and felt they shared characteristics such as socioeconomic status, resilience, and religious conviction with Jeff Buttars were more likely to report a strong emotional response to the story, and more willing to donate time or money to research into William’s condition.

Study subjects’ emotional response to a section of the story in which the parents waited to hear about the outcome of their son’s surgery

There are no foolproof methods for determining someone’s level of empathy, since it does not manifest itself in any one, straightforward way. But psychologists have developed a number of widely recognized tools for measuring basic empathy levels. To make sure that there were no significant differences between the groups in this regard, all subjects completed three empathy scales; the results were taken into account, but did not change the outcome.

Out of 64 individual responses, one was excluded because the subject did not appear to have read the full story. The study’s results are based on the analyses of the remaining 63 responses. (For more details about methodology and data, see this study summary.)

The bigger picture

A research project published this year by American University linguist Naomi S. Baron in her book, Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World, showed that university students prefer print textbooks over their digital counterparts because the students feel they focus and remember better when reading in print. Our study shows no immediate difference in detail memory or engagement between the two platforms. However, it did not take into account the long-term effects of short attention spans and limited memory that some scholars say accompany digital information consumption, and even bleed into print reading. Tufts University neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf says readers in the digital age struggle to maintain enough sustained focus to read great (and long) works of literature, which she experienced firsthand one night when she attempted to read Hermann Hesse’s “The Glass Bead Game” after a long day staring at screens. Nicholas Carr reports a similar change in his own reading habits in his book, The Shallows.

Our study was unlike an authentic reading situation in that we restricted the reading experience by limiting distractions such as wifi and phone use; that level of control carries serious challenges that generally complicate research in the field.

Readers were presented with a task (“read this story”) that most of them naturally tried to complete as quickly and efficiently as possible, while the environment in which they were reading posed few distractions. Real-life readers might lean back in an armchair with a tablet, start to read, and then check an incoming email, continue reading, but watch the story’s embedded video and follow a link to more information, or get tempted by one of the ads on the page. And print readers, too, face distractions from phones, ads, or other stories in a magazine.

Study subjects’ willingness to donate money to research into cortical dysplasia, a medical condition described in the story

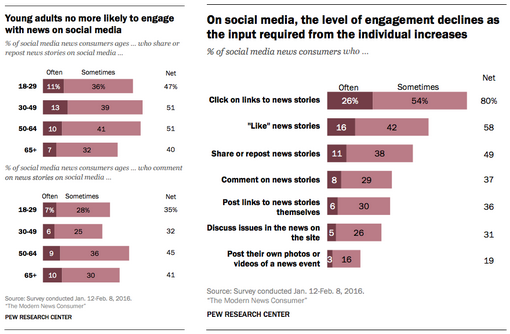

Some studies have shown that the act of reading on a screen differs from the way we’re used to reading in print (on a screen, our eyes scan the text in a nonlinear pattern). But our findings suggest that differences between print and digital reading experiences likely have much less to do with differences in the interfaces themselves than with the way we approach them. If readers are proficient in both domains, it is most likely the design of the online reading experience (with links and ads) that sets it apart from its print counterpart, along with the availability of social media and email on that very same device, says Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, a neuroscientist at the University of Southern California who has studied empathy and narratives.

The good news is that we have imposed those distractions on ourselves—they may not be an inherent part of digital devices—and so we can decide to limit them and minimize their impact. Naomi Baron, who studied students’ reading habits, says that when we sit down to read on a digital device, we have a different set of expectations for that reading experience than we do with a book. We expect to be interrupted and distracted, and don’t fully surrender ourselves to the reading experience.

Because our study subjects approached the digital story with a determination not to be distracted, Baron says, she does not think the results reflect real-life empathic responses to stories in print and on screens, which she still believes could differ.

But our results do suggest that, when properly motivated, people can focus and empathize equally in both contexts. It’s worth noting that our subjects’ relatively high level of education could be a factor here, since highly educated study subjects often perform well in experiments.

Clearly, our study highlights the complexity of studying new online reading habits, and the need for more research. Scholars generally believe that there are different benefits and downsides to reading in print and digitally—the challenge is figuring out what they are, and how to balance them.

For readers and journalists alike, an awareness of that culture of distraction is perhaps the best place to start. When journalist Michael Rubino wrote “The boy with half a brain,” he says, he tried to limit the distractions in his online piece by only adding few links, and debated the downsides of integrating the video.

Rubino says that empathy is essential in his reporting process when writing narrative magazine features, and likewise in the reader’s experience with the piece. “I tried to write the story in a way that people, no matter the platform, could identify with,” Rubino says. “When I started reporting, one of the things I was trying to figure out was, what will appeal to people on a human level and what is the universal thing here?”

He doesn’t distinguish between reading experiences, or adapt his writing to one. “Every reader is going to have distractions, whether in print or digital. My goal is to hook and keep them long enough that those distractions will fade away,” Rubino says. “You just have to be better than the distractions. Or try to be.”

CJR Delacorte Fellows Chris Ip and David Uberti contributed to this research project.