Attorney Floyd Abrams, who represented The New York Times in the 1971 Pentagon Papers case and went on to become America’s leading First Amendment litigator, talked with CJR about President Trump’s unprecedented assault on the press, whether leaks from government officials are appropriate, and how the growing acceptance of speech restrictions is an ominous sign for our democracy. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

CJR: I know you’re busy, so let’s get straight to it. Shortly after the election, you said Donald Trump “may be the greatest threat to the First Amendment since the passage of the Sedition Act of 1798.” Why is he a threat?

Abrams: I don’t think we’ve had anyone who ran for the presidency in a manner which suggested the level of hostility to the press than did Donald Trump. And we certainly haven’t had any president who has made as a central element of his presentation while in office a critique of such venom and threat as we’ve heard in the last month. Now, we don’t know how much is talk and what if anything he may do as president apart from the impact of his words. That in and of itself is important. Any effort to delegitimize the press as a whole and any recitation of statements such the one just a few days ago, saying that the press “is the enemy of the American people,” itself raises serious issues even if he never took any legal steps against the press. Words matter. And the words of the president matter particularly. So a president that basically tells the people that the press is its enemy is engaged in a serious—and deliberately serious—threat to the legitimacy of the press and the role it plays in American society.

CJR: How do you see this as unique to Trump as opposed to say the Nixon administration? Is this more of a wholesale condemnation of the press?

Abrams: Yes. This is an across the board denunciation of any and all press organizations that have published or carried stories which have been critical of the president. That goes well beyond anything President Nixon did. That said, it’s perfectly true to say that throughout American history we’ve had presidents who disparaged the press—Jefferson himself did that more than once, sometimes amusingly, and sometimes not. Teddy Roosevelt authorized a criminal proceeding to be brought against Joseph Pulitzer for certain stories about the construction of the Panama Canal. So, it’s still early—very early—in the Trump administration, but the signs are troubling, and the repeated effort to delegitimize the press as a whole is something new and extremely disturbing.

CJR: How could Trump, with his executive powers, actually launch an assault on the press that could threaten the First Amendment?

Abrams: He could do some of the things that President Nixon made some efforts at doing. The Internal Revenue Service has confidential information about the press leaders as well as everyone else. The Federal Communications Commission has broad authority over the broadcast medium. The Department of Justice has authority to determine when to bring Espionage Act claims. So, there are areas of governmental power and authority which could be called upon if a president were of a mind to do so and was willing to engage in a still more overheated public debate about the bona fides of any effort to do so.

CJR: Trump and others have denounced the culture of “illegal leaks” in Washington and called the “deep state” a threat to our democracy. I’m wondering, what do you see as the difference between leaks by Edward Snowden or Daniel Ellsberg and their role in a functioning democracy, and the recent leak about National Security Adviser Michael Flynn, who was forced to resign after information was released about his meeting with Russian agents before Trump took office?

Abrams: First, let me say that I’m not in favor of all leaks. I don’t think the government should simply be open to anyone who has access to it, and I think that the behavior of WikiLeaks—and in my view sometimes the behavior of Edward Snowden—makes that case. I think there were documents, highly classified documents, made available by Snowden that had nothing to do with domestic surveillance, and a good deal to do with the ordinary and entirely proper efforts of the United States to protect itself in a dangerous world. That said, however, the information provided about former General Flynn seemed to me amongst the most important sort of data that served the public interest in becoming public. I mean here is a situation in which it appears that the very day that President Obama imposed sanctions on Russia that there were conversations, the substance of which we don’t yet know, but conversations between General Flynn and a Russian ambassador and perhaps other Russian authorities. So from my perspective the central issue about him is not that he lied about it to the vice president. Vice presidents have been ignored throughout American history, and I’m sure they’ve been lied to more than once by people who viewed themselves as having more relevant positions. What concerns me is the possibility that General Flynn was essentially saying to a foreign nation that is adverse to our interests: Pay no attention to what the president of the United States is doing, we’ll take care of that down the road. That would be highly improper and perhaps illegal.

CJR: So when people say Snowden was praised for revealing the surveillance of “ordinary citizens,” which is what people who use this argument say Michael Flynn was at the time, as well as Paul Manafort, Trump’s former campaign manager, they are in fact not just ordinary citizens when they are speaking with foreign actors that are known agents, is that correct?

Abrams: Yes. A person who is closely involved with a president-elect is hardly the same as the people that WikiLeaks exposed by printing or making available the Social Security numbers of every sundry employee whose documents happen to come into WikiLeaks’ possession. So the more important the person and the more the person has a potentially direct impact on American public policy, let alone American national security, the more defensible it is in certain circumstances to find out information about his behavior and to reveal it to the public. And I think that’s precisely where the revelations about General Flynn fit.

CJR: This administration has targeted the use of anonymous sources in particular, arguing that they are somehow “fake” or just a product of leaks with political intent. Do you think the press can do a better job of using anonymous sources?

Abrams: Well, a part of this relates to the manner of presentation. Is there a more revealing way to let the public know why the journalistic organization believes these sources are credible? One way they can do that, The New York Times and other publication routinely do, is use numbers. Six confidential sources said this. Where there is a way to identify why this source is credible, without revealing the identity of the source, or providing too much identity on how to determine who the source is, it should be followed. I don’t think this is a fake news problem, this is a credibility problem. And it’s very important at this time that the press say as much as they possible can justifying their reliance on the sources that they have. Otherwise, you just wind up with White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus or President Trump saying there are no sources, and no one having any basis to judge apart from one’s own view as to the credibility of the publisher that’s offering this information to the public.

CJR: In that same vein, you’ve said that the press may need to go on the offensive in terms of using litigation against claims by this administration that certain news stories are “lies” and certain news organizations progenitors of “fake news.”

Abrams: What I’ve said is that there are situations that I could imagine in which statements made by the president or people high in his administration could give rise to libel litigation. Every other democratic nation that I can think of, all of which provide less First Amendment protection than we do, have some body of libel law, and libel suits are brought under them. I don’t believe that it’s illegitimate for the press to avail itself of libel law in certain extraordinary circumstances. Now no one should know better than the press that we protect under the First Amendment a high level—an extraordinary level—of name calling, of generalizations, and rhetorical hyperbole. We do that on purpose. And I don’t think that a general statement—for example, that the news is “fake”—is anything but that. The president is entitled to First Amendment rights as well as everyone else. And it’s important for the public to be able to hear and pass judgment on the president, and what he’s saying, and what he’s thinking. But there are things that might be said about particular journalists or particular news organizations which are false and known to be false by the person saying them. While the press is understandably used to defending libel suits, it ought to bear in mind that it has rights, too. And if the charges against it are clear enough, false enough—obviously known to be false—I think it should not give up the chance to use all the protections that the law affords it.

CJR: You famously represented the plaintiff in Citizens United defending the First Amendment rights of a conservative nonprofit corporation. Do you see the assault on free speech coming not just from Trump but also from “speech codes” and other speech restrictions on college campuses? Is there some relationship between what’s happening with restrictions on speech on the left and what’s happening on the right?

Abrams: I don’t think one causes the other. But I do think that the farther down the road we go of limiting speech, whether it’s of the left or the right, the easier it is to use that precedent to limit others’ speech. So, yes, on campuses one of the main victims, and they are victims, of suppression of speech has been conservative groups. At Fordham University in 2012 here in New York, for example, the Republican Club wanted to invite Ann Coulter to speak and they weren’t allowed to do it. Basically the school said it would be alright if you had her on a panel. That’s a sort of disgraceful suppression of speech, and it’s occurred elsewhere at many universities. In 2013, the New York City police commissioner at the time, Ray Kelly, was shouted down at Brown University. Last year, the Israeli mayor of Jerusalem was shouted down at San Francisco State. We’ve got a lot of situations in which speech has been limited or suppressed in an unacceptable way. Now I have to say, I don’t think that President Trump would behave any differently than he does, or would have any different views than he does, whether or not this campus plague of speech suppression had occurred. But I am concerned that there has been on both sides and in a number of different contexts a willingness to limit speech, punish speakers, and otherwise act in a contrary way to both the law and the spirit of the First Amendment.

CJR: A 2015 survey of some 800 undergraduate students, sponsored by the William F. Buckley Jr. Program at Yale, found that 51 percent of students favor their school having speech codes and trigger warnings. Nearly one-third of the students could not name the constitutional amendment dealing with free speech. And 35 percent said that the First Amendment does not protect “hate speech.” Does that make it easier for the president and his administration to attack speech they disapprove of and the press in general?

Abrams: Well, yes it does. I’ve thought for some time that one of the real contributions of any administration would be to take whatever steps they could to re-impose a requirement of a civics course in junior high schools or high schools in America. We need people who are educated about the Constitution in general and the First Amendment in particular at young ages, not the moment they get into college. But to the extent that we are moving towards living in a nation that simply accepts the notion that speech which is viewed as unhealthy or troubling should not occur, First Amendment norms fall easily. And to be clear, I mean First Amendment norms on the broadest level not just legal violations of the First Amendment but what I referred to earlier as the spirit of the First Amendment; that is an acceptance of the notion that people will have a lot of different views on a lot of different subjects, many of which will be difficult or even impossible to seem to live with, but which we at our best have always protected.

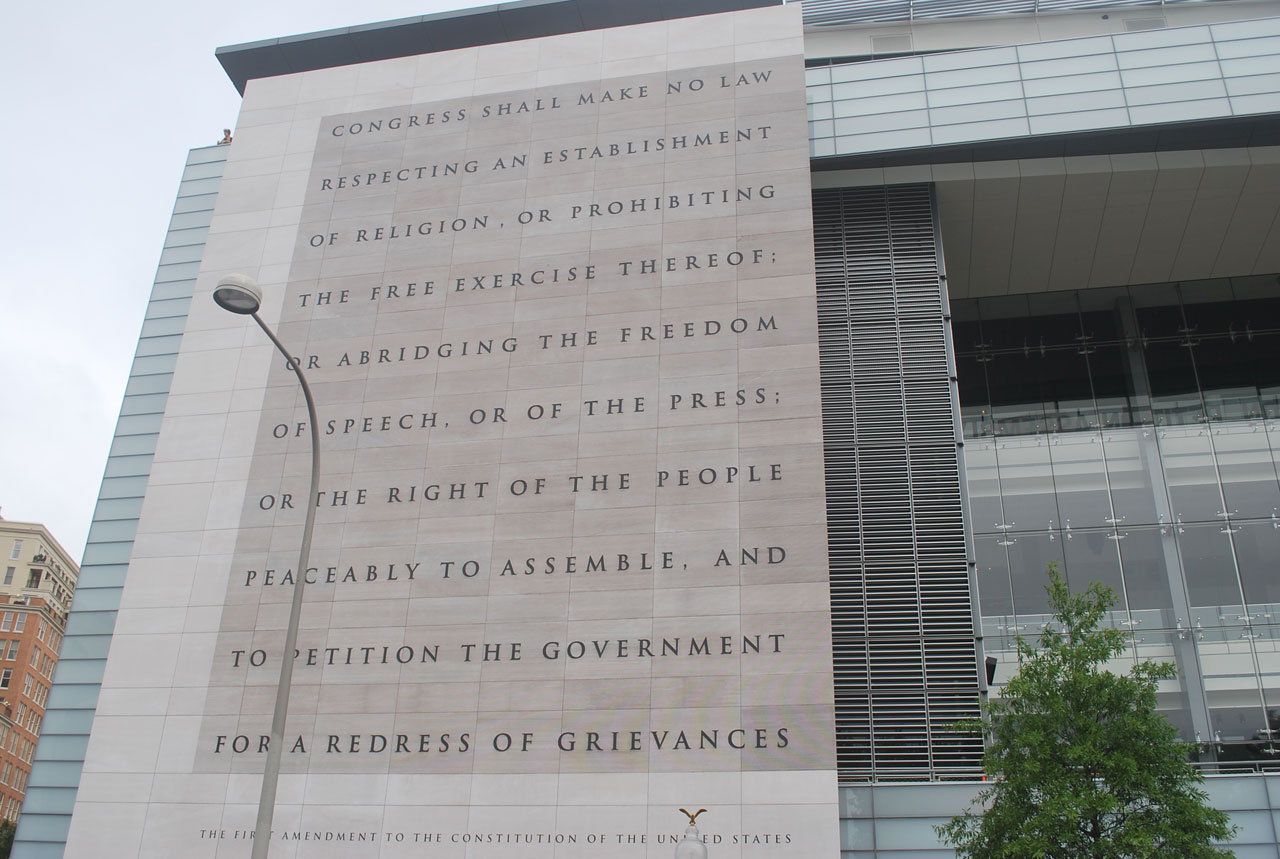

CJR: It’s interesting that you bring up that civics course. I was just discussing this with Jeffrey Herbst, president of the Newseum in Washington, DC, which does a lot of outreach to try to teach young people about the First Amendment, but also about how to be a consumer of news, which to me seems extremely important.

Abrams: I couldn’t agree more. And this one is not Donald Trump’s fault, or one party’s fault, or one view of the country’s fault. We really have abandoned our children to a very great degree in terms of teaching them what it is that makes the country so special, including the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the First Amendment. And it’s something which I think has to be taught while people are young. I don’t blame college kids who get in and want people to behave nicely to each other. A lot of bad speech is nice speech. So it asks a lot of them to just pick up the notion that this is the price we have to pay to live in a free country, and that sort of teaching has to start much earlier.

CJR: Final question. Are you hopeful that, as much change as we’ve gone through in the news industry, the First Amendment will prevail and we’ll continue to see the press’s watchdog role played in different forms, through different business models, online and elsewhere?

Abrams: On that I am optimistic. I think the public wants it. I think there will be a market for it. Whether the press will be powerful enough to fend off presidential power is one issue. But on the broader issue of whether we’re likely to continue to have a press that exists in a meaningful way and does continue to fight the good fight, I think that’s more likely than not. That’s one of the big advantages of having written the Bill of Rights down. I start out my latest book, The Soul of the First Amendment, talking about the Framers arguing whether to have a Bill of Rights at all. In Philadelphia, they voted against the Bill of Rights—unanimously. And Alexander Hamilton wrote in The Federalist, why should we write down something which is so unnecessary? We never said Congress could limit the press; why do we have to say it can’t? And if the ultimate decision had not been made to have a written First Amendment—which is law, not just a political-science essay—we would live in a very different country. Because we have a First Amendment, I think it will continue to protect us against the widest range of challenges.

Michael Judge is a freelance journalist, editor, poet, and a former deputy editorial features editor at The Wall Street Journal.