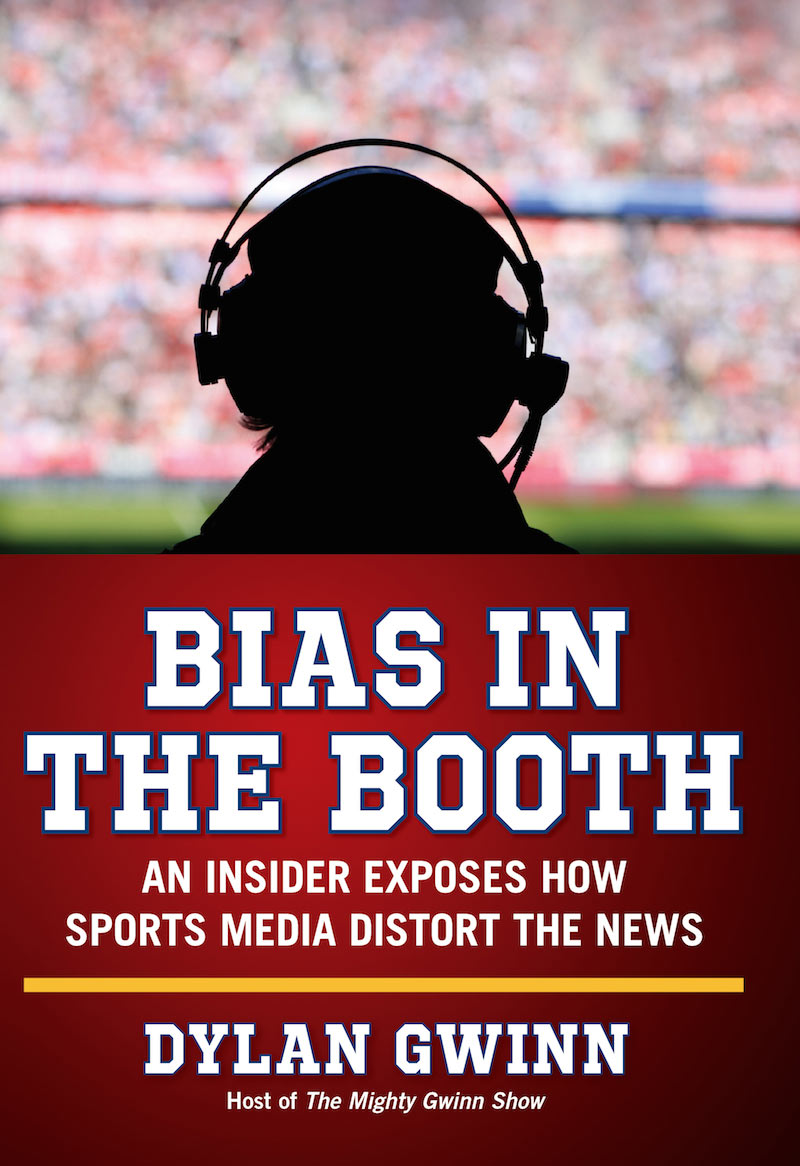

Bias in the Booth: An Insider Exposes How Sports Media Distort the News

By Dylan Gwinn

Regnery Publishing

272 pages, $27.99

You can say this for Dylan Gwinn, at least: He gets to the point. A mere two paragraphs into his new book, Bias in the Booth: An Insider Exposes How Sports Media Distorts the News, Gwinn has already asserted his provocative thesis: “This is a book about how virtually the entire sports media have been overrun with liberal activists trying to implement and advance their liberal agenda.” This is a man with no time or patience for rhetorical foreplay, and I, for one, applaud his directness. America’s book-readers are busy people, and authors who encapsulate their theses right up top like this are doing these readers a favor by helping them determine whether or not a book is worth their time.

So I’m sure Gwinn will understand if I, too, am direct: This book is not worth your time. This book is very dumb. This book exposes nothing except its author’s own rhetorical limitations. A keening, bitter catalog of slights and allegations of willful journalistic malpractice, Bias in the Booth is less an analysis than a screed, reliant on ad hominem attacks, suppositions, and generalizations in its bid to document the purported liberal bias of American sports media.

Many sports journalists undoubtedly do consider themselves liberals. But Gwinn too often simply asserts this liberalism without providing supporting evidence, and then assumes a causal relationship between these journalists’ presumed personal beliefs and the stories they choose to cover. His shaky premises ultimately serve to undermine the entire book. Bias in the Booth might be worth reading for entertainment’s sake, depending on your taste for bombastic conservative agita, but it is not worth taking seriously.

That’s a shame, because there’s an interesting book to be written about how the political rhetoric of sport has evolved in the internet era, and how athletic imagery can be manipulated for cultural and political ends. I would love to see a serious conservative writer address these topics, and critically examine whether the rise of hamster-wheel journalism and opinionated online commentary have made it easier to use sports and sports media as platforms for political statements.

Gwinn is not the man to do it. A sports radio host in Houston, Gwinn’s writing style leans heavily on quips, bluster, and presumptions. In his book, he adopts the persona of an aggrieved sporting everyman, speaking up for the common fan, who is forever “wanting to shout, ‘Shut up and give me the box score!'” He writes from a standpoint of what the critic Jim Sleeper has called ressentiment: a keen sense of his own disempowerment in a world that has been rearranged without his knowledge or consent; a feeling that the best way to resist the winds of change is to yell into them.

Gwinn considers sports a form of escapism, a refuge from the world of serious things, and he resents any violation of this sacred, purportedly neutral space. “Like many of you,” he writes, “I remember a time when people flocked to sports because they were fun and entertaining, even awe-inspiring at their best, and an escape from the BS and politically correct hysteria of the ‘real world.'”

But those halcyon days are gone, Gwinn writes, thanks to joyless PC scolds intent on making every kickoff and first pitch a forum for liberal political commentary. He sees evidence for this everywhere. The movement to get the Washington Redskins football team to change its name to something that couldn’t be interpreted as a racial slur? Nothing but “holier-than-thou groupthink” from liberal sports commentators who “want to feel like their careers mean something.” What about the publicity given to Michael Sam, or the basketball player Jason Collins? Easy: “Professional sports leagues are keenly aware that gay activism has become the new liberal cause célèbre, and they want to be at its forefront.” The growing consensus that football is a dangerous game, and that its players risk traumatic brain injury and other health problems? An attempt by the “liberal sports media” to destroy a sport that they consider “the ultimate expression of the unreformed American spirit—chauvinistic, competitive, and even too Christian.”

Gwinn can’t stand it, and he assumes that you can’t, either. “Almost every sports fan wants sports to be a politics-free zone, and our job as media isn’t to insert realism into people’s escapism,” he writes. This sort of assumed consensus—“almost every sports fan,” as if Dylan Gwinn spends his nights and weekends standing in stadium parking lots handing out surveys—might play well on talk radio, but it’s exhausting when translated into print. Gwinn writes with all the subtlety you’d expect from someone who spends his days arguing with people named “Car Phone John.” The book is filled with lazy, fraught terms like “thought police,” and “left-wing media machine.” Twitter users who assert liberal opinions are “mouth-breathers in their pajamas.” “We’re fast approaching the point where there’s going to be no real difference between Bob Costas and Rachel Maddow,” Gwinn writes. “Except one of them is a man. I think.”

I’m all for insult comedy, but when it comprises this much of your argument, it’s usually an indication that you don’t actually have much of an argument. And Gwinn doesn’t. He has observations and assumptions, lots of them, but fails to assemble them into a coherent, persuasive case for a systemic liberal bias in American sports media. While Gwinn asserts that the politicization of sport and the surrounding discourse is a new phenomenon, he fails to adequately prove this, instead repeatedly appealing to loose feelings of nostalgia as evidence that things used to be different. “Political news and commentary were something you didn’t often find in sports, because they were contentious and harsh, a serious business where the burdens of the real world were hung around your neck,” Gwinn writes in his introduction.

But public sport has been a political activity since antiquity, and not just in the “bread and circuses” sense. Sport is a reflection and reinforcement of cultural norms, and for most of the 20th century, I would contend, sport was a tool for reinforcing heteronormative masculinity and the illusion of meritocracy. It still is, to a very real extent, and Gwinn surely knows this. Almost every single professional sporting event in America will, at some point, pause to salute a military veteran in attendance. When this person is announced, fans are expected to rise and cheer. “God Bless America” is usually sung. This is political.

But cultural norms are shifting, in part because “the media” is no longer as monolithically insular as it once was, no longer in a position to uniformly define and reinforce those norms. The rise of the internet has disaggregated reporting and commentary and made it easier for unorthodox voices to work their way into the sporting conversation. Gwinn ascribes this shift to a pervasive and inchoate liberalism that has poisoned the press box like toxic runoff seeping into groundwater.

Though Gwinn claims he is equally opposed to all forms of politicized sporting rhetoric, it is clear that he is really upset that a bunch of political liberals have seized the microphone. “For the sports media, the enemy is always the same: conservatives and Christians,” writes Gwinn. “The ‘ground’ the liberal sports media want to break is the ground of traditional Christian morality.”

Gwinn contrasts the coverage of Collins and Sam with the coverage of Tim Tebow, the former University of Florida quarterback and avowed Christian whose brief stint in the NFL was marked by underwhelming on-field performance and overwhelming off-field coverage. Tebow, claims Gwinn, was “marked for destruction” by the liberal media, who focused their coverage on Tebow’s athletic limitations and religious beliefs, and occasionally seemed eager to see the quarterback fail. “Could you imagine if Tebow had shouted, “Jesus is coming!” before running a zone read or a quarterback sneak?” Gwinn asks. (He is very fond of arguing via hypotheticals.) “Bob Costas would have had a stroke.”

This is inane. Before, during, and after his short stint in the NFL, Tim Tebow received more media coverage than most athletes in recent memory. ESPN openly instructed its on-air personalities that “you can’t talk enough Tebow.” If Tebow had yelled “Jesus is coming!” during a football game for some reason, the story would have led SportsCenter for weeks, and the NFL would have sold a million Tebow jerseys. Certain individual bloggers and reporters might have disliked Tebow for his personal beliefs, but “the media” as an entity couldn’t get enough of him.

Gwinn ignores this, perhaps because it indicates something that might contradict his dyspeptic thesis. It seems obvious that the real difference between today’s sporting scene and that of Gwinn’s youth is the arrival of huge sums of money into sporting ownership. Sports teams are billion-dollar corporations; sports broadcast contracts are billion-dollar businesses, too. The Los Angeles Clippers, a historically terrible NBA team, recently sold for $2 billion. The people who have bought into this industry have billions of reasons to want to protect and grow their investments.

So, okay, big corporations are simultaneously cautious and avaricious. They are loath to offend consumer groups. This is why the Clippers’ former owner, Donald Sterling, was forced to sell the team after audio recordings surfaced of him making racially insensitive statements. This is why Rush Limbaugh was forced out of the Monday Night Football broadcast booth after suggesting that the former Eagles quarterback Donovan McNabb, who is black, owed his prominence not to his athletic talents, but to his skin color. The sporting “powers that be” squelch this sort of racially charged commentary not because they are liberals, but because they are capitalists.

And because they are capitalists, when they have a product that’s worth selling, they will go all out in their efforts to sell it. Michael Sam and Jason Collins get a lot of media coverage for the same reason that Tim Tebow gets a lot of coverage: They are extremely marketable. (Though not necessarily employable: None of them is currently on a professional sports team’s active roster.) Do these stories travel farther and resound louder in this age of media disintermediation than they did in the networks-and-newspapers days? Sure. But it’s not because of some liberal media conspiracy. That’s my take, at least. Now I’ll hang up and listen for Dylan Gwinn’s answer.

Justin Peters is editor-at-large of the Columbia Journalism Review.