Lillian Ross is on the phone. Were she the one reporting this piece, the phone is the last place she’d be, but in this case Ross is the subject and the subject is 97 years old, and some days, at that age, you just don’t feel up to having someone over to your apartment. I cancelled my trip to visit her in New York and instead gave her a call. “This is kind of fun,” she says. “I’ve never done this before.”

The occasion for this piece—a big writer with a new book out—feels perfect for The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town, where Ross mastered the art of brief, revealing stories about the famous and less famous using scenes, dialogue and a novelist’s eye for details and pacing. Before there was the New Journalism, there was Lillian Ross, with her French Clairefontaine notepads, getting out of the office, away from the phone, and jotting down everything she heard and saw—“That girl,” Edmund Wilson once wrote, “with the built-in tape recorder.”

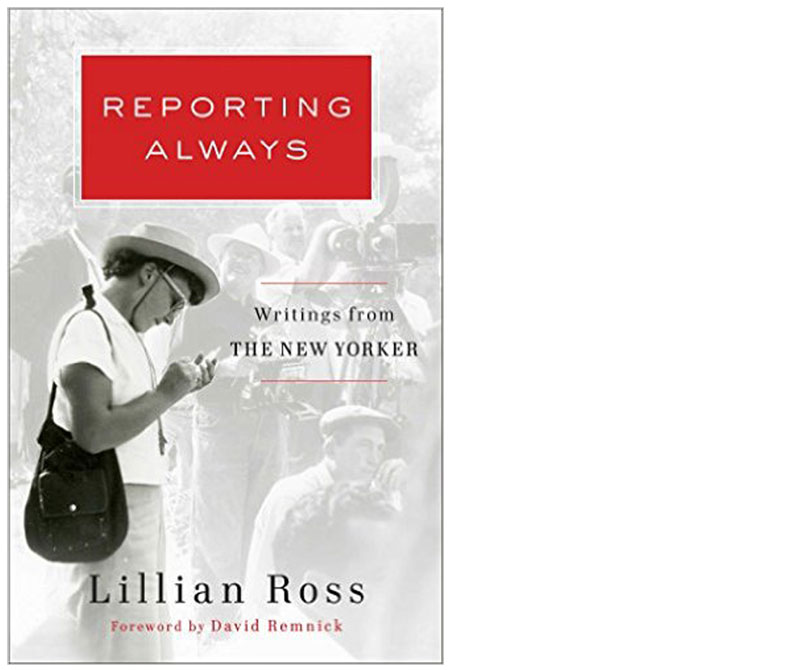

That girl, who grew up to become not just one of the most important female reporters in history but a singular if under-appreciated influence on generations of journalists, just published Reporting Always, a collection of her New Yorker journalism, from her “Talk” pieces about Julie Andrews, Edward Albee, and Robin Williams, to her long profiles of the bullfighter Sidney Franklin and bullfight aficionado Ernest Hemingway. The book, I hope, will amplify her stature as one of the giants.

Reporting Always

Slideshow excerpted from Reporting Always by Lillian Ross. Copyright ©2015 by Lillian Ross. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Ross’ work has been inexplicably ignored by several anthologies of literary journalism, even though she was doing it, and doing it masterfully, while Gay Talese and Tom Wolfe were in high school. In Cold Blood, Truman Capote’s famous nonfiction novel, was published in 1966. Ross’ Picture, celebrated nonfiction novel about John Huston’s filming of The Red Badge of Courage, was published 15 years earlier. In describing the idea to her editor (and later her lover) William Shawn, she wrote: “I don’t know whether this sort of thing has ever been done before, but I don’t see why I shouldn’t try to do a fact piece in novel form, or maybe a novel in fact form.”

Long-time New Yorker writer Susan Orlean is an admirer of Ross and her work, though Ross’ career, Orlean told me, has been “somewhat underappreciated.”

“Her work is so modern when you look at it now, in terms of approach and tone and voice,” Orlean says. “It kind of prefigured a lot of what we think of as New Journalism far earlier than we think of New Journalism happening. She’s the consummate reporter, listener and observer, and she writes with tremendous confidence and flair, all of the qualities that we marvel at in work that kind of came after her.”

Ross is retired now, living on the Upper East Side in adjoining apartments with her son Erik. We’re not the only people on the phone. Susan Morrison, who edits the “Talk of the Town,” is on from her office at The New Yorker. Ross’ last “Talk” piece appeared in 2011, but she still calls Morrison with ideas, and that makes Morrison still her editor, as she has been since 1997. Several times during the conversation, Ross, as she did throughout her career, turns the attention away from herself —first to me, asking “What are you doing down there in Washington?” and then to Morrison, describing how “brilliant” she is at editing “Talk.”

“Lillian,” Morrison says, “back to your career.”

Ross joined The New Yorker in 1945, when Harold Ross, the magazine’s founding editor, got around to hiring women with many of his men off at war. “The idea,” Ross writes in the book’s introduction, “was that we women would report the ‘facts’ for “Talk” stories, and then these would be handed off to the remaining men on staff, who would ‘rewrite’ them.” The practice was eventually scrapped in 1952 when Shawn became the magazine’s editor. By then, Ross was also off reporting longer stories, including a profile in Mexico of Franklin, the bullfighter.

“A lot of young women at the magazine find the beginning of your career enormously inspiring,” Morrison says to Ross. “You were off driving through Mexico, doing things that other women weren’t doing at the time.”

Ross’ reaction: “I never thought of it that way. As a matter of fact, that whole feminist, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem stuff was always kind of annoying, and still is. It was reporting.”

Ross had a more varied career than many of her colleagues, especially her close friend Joseph Mitchell, whose beat was almost exclusively New York’s unsung street characters. Ross liked the unsung, writing wonderful stories about high school students visiting New York and women vying for Miss America, but she was also interested in the well known—not for their fame, she tells me, but because “they are all human beings. Everyone is trying to find a way to live and obtain something good for what they want in life. That to me is interesting.” She wrote about Hollywood celebrities in their homes, spending time with their families, in the back seat of cabs, revealing themselves in the most ordinary ways.

“One of the things you did in the Hollywood pieces was to treat these people just like regular people,” Morrison says. “You did normal human things with them rather than put them up on some glamorous pedestal.”

“The glamorous pedestal I left to the people who look for that and still do,” Ross says.

Morrison: “You weren’t impressed.”

Ross: “Well it’s not what’s interesting about them.”

With her Hemingway profile—her masterpiece, in my opinion—she spends a couple days with him in New York shopping for a coat, hanging out in his hotel (Marlene Dietrich stops by), and visiting museums. In a scene with him arriving at the airport, she shows Hemingway’s habit of talking like an Indian. Hemingway had apparently let his seat companion on the plane read a manuscript of a new book.

“He read book all way up on plane,” Hemingway said. “He like book, I think.”

Hemingway loved the piece, and the two became friends, but many readers thought Ross savaged him, embarrassing him by capturing the way he sometimes spoke and recounting intimate details of his private life, which differed with how readers imagined him. “What’s a writer supposed to be?” Ross asks me. “A man sitting by the fireplace with a pipe in his mouth? That’s propaganda. It’s not like that. A writer has his own real life and his own way of being and his own real troubles.”

A few years ago, Ross discussed and annotated the piece in an interview with the writer Elon Green at NiemanStoryboard.

“The bartender brought the drinks,” Ross wrote in the piece. “Hemingway took several large swallows and said he gets along fine with animals, sometimes better than with human beings. In Montana, once, he lived with a bear, and the bear slept with him, got drunk with him, and was a close friend.”

Green asked, “Was there any attempt to verify this? It seems … suspect.”

Ross replied, “Why be so literal? If that’s the way he remembered it, what does it matter? What’s interesting is the way he tells it—that’s what matters.”

Green notices there is almost no exposition in the piece.

“I didn’t need it,” Ross told him. “Who am I to add exposition? I don’t write that way.”

No, just accumulate details and facts, in one scene after another—that’s Ross. In rereading that piece and the rest of Reporting Always, it’s easy for me to see how influenced she was by Hemingway and his pared-down style. I ask her about that. “The mechanics of writing, or what you call style, is just writing to me,” she says. “It affected me very strongly because of the clarity, the originality, the excitement and wonder of directness and simplicity.”

Towards the end of the piece, Ross has plans to visit the Met with Hemingway. They’re at the hotel. “Hemingway came out in a little while, wearing his new coat,” she wrote. “It was raining, and we hurried into a taxi. On the way to the Metropolitan, Hemingway said very little; he just hummed to himself and watched the street.” He spotted some birds in the sky. “In this town, birds fly, but they’re not serious about it,” he said. “New York birds don’t climb.”

Michael Rosenwald is a reporter at the Washington Post. He has also written for The New Yorker, Esquire, and The Economist. Follow him on Twitter @mikerosenwald.