The 2016 election cycle has been one of the costliest so far, and one of the most unpredictable. Roller-coaster shifts in voter poll data, a cobweb of campaign money, and the reportedly disproportionate attention media outlets have given—or refused to give—to populist and independent candidates have stymied pollsters and pundits.

Social media data—a forever-changing landscape of opinions and content, much of which is visual (think videos and GIFs)—is considered too murky to be taken seriously for any kind of analytics. Even text-based posts are spiced with slang and popular lingo that makes systematic rendering and analysis almost impossible. Yet this liveliness is arguably the essence and perhaps the advantage of social media over polls. If only we could capture the hidden value trapped inside the buzz.

When it comes to social media, factors such as popularity, “virality,” and name recognition are visible in the number of followers, likes, shares, and geographic data attributed to a post. For Twitter and Instagram, most of this data is public, or quite easily acquirable. Facebook, meanwhile, remains reluctant to provide public and usable API’s to social asset management tools that are frequently used in newsrooms today, such as SAM Desk and Dataminr.

There have been one or two very focused analyses on how user interactions over social media might reflect voter turnout during the presidential primaries, but many similar stories failed because they highlighted one variable, such as Facebook likes or Twitter followers, while acknowledging the insufficiency of relying on that single variable.

Social media will not predict the outcomes of the primaries or the general election. But the accumulated data offers new tools to vet candidates and how they use social media for campaigning, and shows how followers and potential voters react to the candidate they most like or hate.

Instead of parsing Facebook likes and Twitter followers, journalists could look into whether users (and potential voters) favor posts by candidates about particular policies and promised changes. Recently, along with other students from the Columbia Journalism School and the university statistics department, I drilled into social media data related to the presidential primaries as part of a series of hackathons designed to bring together data and computational journalism students with students training in data science and statistics.

Under “data,” think every presidential candidate’s tweets and Facebook posts since he or she announced a run for office, as well as their accompanying metadata (such as how many followers or likes that candidate’s account had at the time each post was published). The data, most of which began being generated last spring, was supplied by Voxgov.com, a non-partisan analytics startup specializing in government communications, including politicians’ social media presence.

Our initial approach was to test whether presidential candidates used Twitter to trumpet their policy proposals. For the analysis, the group built separate “dictionaries” of thematic words related to one or more categories, such as education, employment, or foreign policy. It turns out that candidates mainly use social media to reflect on policy issues if they are prompted to do so during an interview, a presidential debate, or a public event covered by the media—or by their peers running for office. Interestingly, the bulk of candidates’ posts serve as advertisements, like when Ted Cruz, John Kasich, or Jeb Bush used Twitter to promote fundraising events and ask for campaign donations. Unsurprisingly, candidates also often used tweets to criticize their opponents.

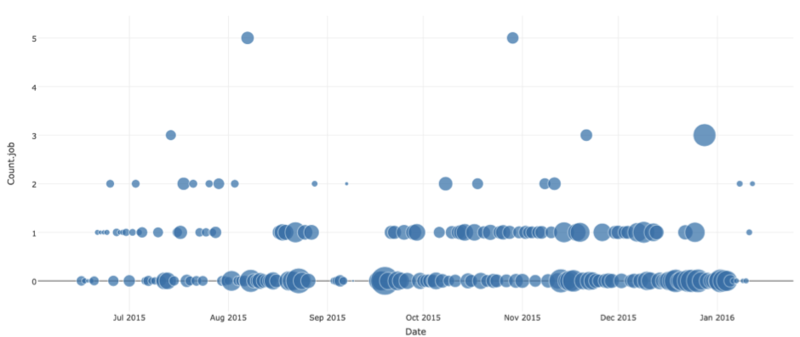

The plot below shows the times Trump tweeted about employment (including the word “employment,” as well as “job,” “employer,” “wage,” and related words). Most of those job-related tweets appeared on debate days, with mentions cresting on August 7 and October 28, 2015, two nights when Trump struck politically lethal blows to Bush and Cruz. On each of those days, he had five job-related tweets compared to an average of around one job-related tweet every three days.

Social media can also be used to gauge trends in popularity. Attitudes change rapidly, and social media can be the best platform to catch those swings. The cumulative nature of posts and tweets would suggest that the more followers or shares a candidate collects (and retains over time), the more powerful that candidate will be.

But even a brief probe into some candidates’ popularity trajectory via social media yields counterintuitive results. Journalists could ask, for instance, whether the popularity of a candidate’s remarks is contingent upon the sheer volume of his or her social media followers—or can certain comments and behavior reach far beyond a candidate’s existing audience?

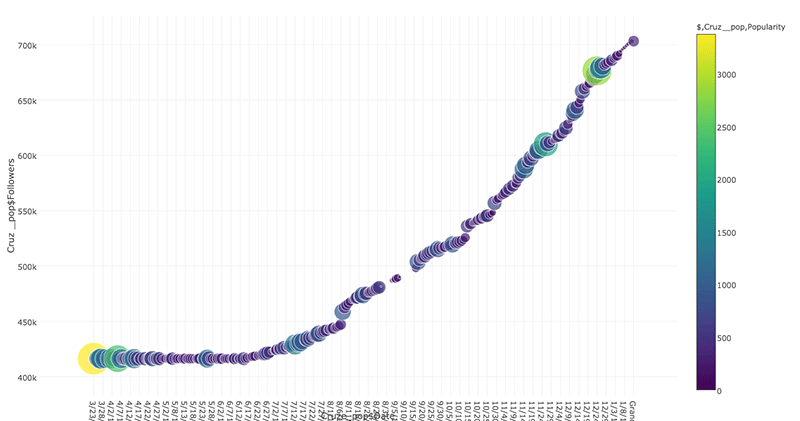

In the graph below, see how Cruz’s most popular tweets were shared the most when he had a fraction of his current 1.12 million total followers. The two wide and light circles at the lower left corner of the graph represent the most “engagement” (aggregate of the number of retweets and favorites) of all of Cruz’s tweets. He never equaled his early popularity on Twitter, even after gaining another 300,000 followers.

There are many opportunities to creatively probe social media data. At a minimum, tracking the engagement a candidate is able to create among social media followers can indicate how “likeable” the candidate is. Social media engagement also tends to correlate to a candidate’s legacy media momentum over time.

Social media is an important repository of live data streams. It is also a historical record, capturing ebbs and flows of support for a political idea or candidate, and avoiding the fundamental snapshot nature of polls. The first draft of history today might be written through a real-time data stream. With creative thinking and analysis, journalists can capture that.

Bernat Ivancsics a multilingual business and data journalist, currently a PhD candidate at the Columbia Journalism School, who focuses on the emergent trends of computational journalism and the social history of public records in the United States.