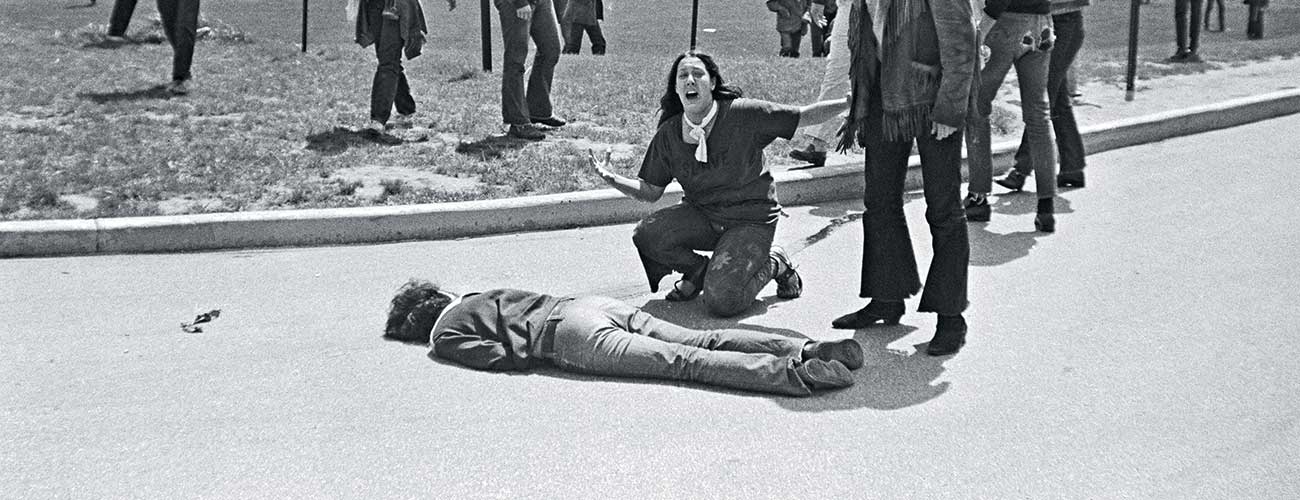

It is a photograph all young journalists should pin to their cubicle walls: the iconic image of the 1970 Kent State shootings, in which a teenage girl grieves over the body of a slain student.

Forget for a moment that the picture is among the most famous in US history, or that the photographer—a 21-year-old Kent State journalism student named John Filo—risked his life to document the tragedy.

Consider what the photo captures: Our own military occupied a public university and then opened fire on a crowd of unarmed citizens—students no less—killing four and wounding nine. One student was killed while walking to class.

Filo’s photo is a striking reminder of how quickly the world can turn upside down and how people in trusted, powerful positions can commit the most horrendous acts.

I was a student at Kent State in the early ’80s, a decade after the shootings. Even then, it was difficult not to be shaped by the deaths and Filo’s renowned photo. Questions about the shootings lingered: Why did the guardsmen fire? Were certain student protesters targeted?

A central part of the Ohio campus seemed to me like a giant crime scene, and I often wondered: Am I walking over the very spot where someone was shot? Am I parking my car where someone died?

The answer to both questions was yes, but I didn’t know any better. Most students didn’t. There was no proper memorial. There was no museum. There were no signs. School officials wanted to move on.

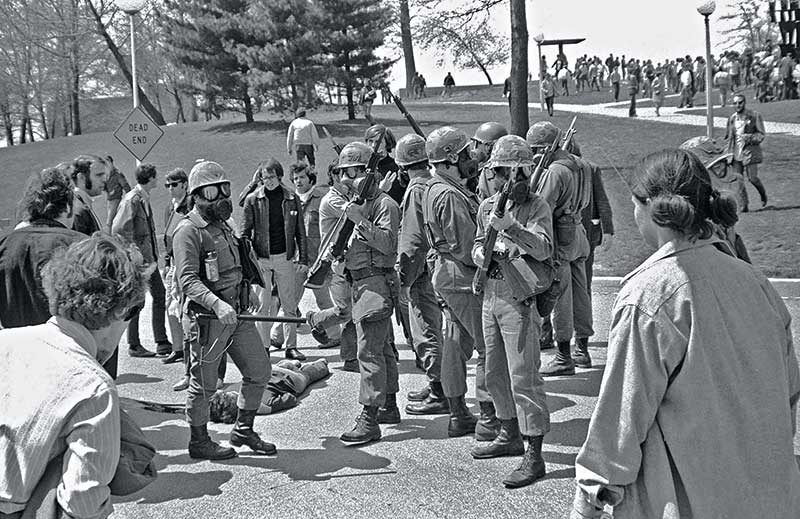

Student Alan Canfora waves a black flag at Ohio Army National Guardsmen as they kneel and aim their rifles on a KSU football field. Shortly after this picture was taken (though from a different location), the soldiers fired upon students, killing four.

But we did have one thing: We had Filo’s photograph. Like the police shooting videos of today, it provided a sliver of justice, proof that what happened really happened, and hope that the events would not be whitewashed.

When I called Filo, now 67 and vice president for photography at CBS, he recalled his concern that authorities would confiscate his film that day and concoct a false version of events. Early radio reports, he says, characterized the tragedy as a shootout between students and the Ohio National Guard, with guardsmen also being killed—all untrue.

After the shootings, Filo was startled to see guardsmen cutting telephone wires on a main road out of town. He hid his film under the hood of his red VW bug and drove straight to Pennsylvania. Only when he was over the border did he pull into a rest stop, put his film in a canvas bag behind the front seat, and use a pay phone to call his hometown paper near Pittsburgh.

“Did you get any pictures?” a photo editor asked.

“I think so,” Filo responded.

His picture of the girl screaming over the slain student went out over the Associated Press wire and was published on the front pages of hundreds of newspapers worldwide. But the backlash, Filo recalls, was immediate. “I started getting hate calls. I got tons of hate mail. They said, ‘This never happened. This is obviously a posed photo. It didn’t really happen.’ ” Even some other professional photographers were skeptical, suggesting he sign an affidavit.

People were in denial, Filo says. “This was a shock to America.” The photo went on to win the 1971 Pulitzer Prize for spot news photography and become a fixture in history books.

Filo’s photo is a striking reminder of how quickly the world can turn upside down and how people in trusted, powerful positions can commit the most horrendous acts.

“There are really only a handful of photographs that singularly have frozen a historic moment in time that almost everyone can instantly recall in their mind,” says Pete Souza, chief official White House photographer for President Barack Obama. “John Filo’s photograph of the Kent State shootings is certainly one of those. All you need to do is mention that episode in American history to anyone, and they remember that photograph. The details may be a bit foggy of what actually happened that day, but no one will ever forget that image.”

The irony is that Filo, at the time a senior majoring in photo illustration, didn’t want to take any pictures that fateful spring day.

Four days earlier, President Richard Nixon had announced on national TV that US troops were moving into Cambodia, in effect widening the Vietnam War. The news sparked student anti-war protests the next day on campuses across the country, including at Kent State. That night, protesters in downtown Kent, Ohio, broke windows, set bonfires in the street, and hurled bottles at police cars. The following day, guardsmen were called to campus, only to find the wooden ROTC building being burned to the ground.

But Filo was 200 miles away, in the forests of central Pennsylvania, finishing the requirements of his senior portfolio by photographing extreme close-ups of tiny flora, such as moss and teaberries.

When he arrived back on campus and learned of the unrest, he was convinced he had missed the biggest story of his life. Making matters worse, many of his classmates had signed on with major publications, such as Life and Newsweek, to photograph any additional protests. No one needed Filo’s help. “I was totally, totally dejected,” he says. “I don’t think I could have felt any lower.”

The following morning, May 4, the day of the shootings, he reported as usual to the journalism building, where he worked in the photo lab mixing chemicals and handing out equipment to students. When two professors spotted Filo moping around, they encouraged him to use his lunch break to photograph a student rally. Filo grudgingly picked up his camera, stuffed six rolls of black and white film in his right pants pocket, and headed out.

He was surprised to see the Commons, a field adjacent to the journalism building, packed with about 3,000 demonstrators and spectators. Guardsmen fired tear gas canisters to try to get them to disperse. Several photographers set up their cameras on tripods on the edge of the field, but Filo followed some guardsmen to the other side of the journalism building. Students hurled rocks at the troops.

A few moments later, Filo started up a hill, where dozens of guardsmen carrying high-velocity M-1 rifles had gathered. “As I was walking up the hill, I saw students turning and fleeing and almost running me over,” he recalls. “So I’m dodging bodies fleeing, and then you hear guns going off, and you realize the guard has started firing.”

National Guardsmen and demonstrators gather around the body of student Jeffrey Miller. Three other students were also shot and killed by guardsmen during the incident.

At first, Filo thought the guardsmen were just trying to scare the students by shooting blanks. “I said, ‘Well, I got to get a picture of this.’ ”

He kept walking toward the guardsmen, coming within about 30 yards, not imagining they were firing real bullets. “I could see no reason to be firing from the top of the hill, shooting downhill at fleeing students,” Filo says.

He stood by a metal sculpture and trained his camera on a guardsman, who fired toward him. “A bullet slams into the metal sculpture, and it erupts in a cloud of rust, and the bullet hits the tree that’s next to me, and a chunk of bark comes off. And I went, ‘Oh, God! Someone is using live ammunition!’ ” Filo says.

Twenty-eight guardsmen fired between 61 and 67 shots over 13 seconds. When the firing stopped, Filo checked his thighs and stomach to see if he had been shot. He was OK. “I go, ‘This is crazy! I got to flee. I got to run.’ ”

He took three large steps down the hill, and then remembered the shooting was over and that he should be taking photos and not running. A few yards in front of him, face down on an access road, lay the body of 20-year-old student protester Jeffrey Miller. Blood was streaming from his mouth.

Filo recalls that the student was clearly dead, and he started taking pictures of him. A few seconds later, a girl with long, dark hair ran up and knelt over the body. Filo says he thought: “OK, this is a good picture. But I’m running out of film.”

He inched closer to the girl. “I’m trying to focus, and all of a sudden she lets out this scream”—and that’s when Filo captured his acclaimed picture. “I advance the camera, and I shoot another picture, and I advance one more, and I’m out of film.”

Like the police shooting videos of today, it provided a sliver of justice, proof that what happened really happened, and hope that events would not be whitewashed.

By the time he reloaded his camera, the girl was gone. Filo continued to photograph other people’s reactions to the body, angering some students. They yelled: “Why are you doing this?” and “What kind of pig are you, taking pictures of this?” Filo says he yelled back: “No one is going to believe this happened!”

The image of the girl kneeling over the student has often been compared to the Pietà, the depiction of the Virgin Mary holding the body of Jesus. Filo says he sees similarities, but didn’t at the time. “When it’s happening,” he says, “you’re reacting to a scream, a movement.”

Only two weeks later did Filo learn that the girl was not a Kent State student but 14-year-old Mary Ann Vecchio, a runaway from Florida. “There were plenty of other women around who were 18, 19, and 20 years old who didn’t react like she did,” Filo says. “So you’re saying, ‘My God, I had this child react to this gore and horror in front of her. Had she been a student, would she have screamed? Would she have done that? And would the picture have been different?’ ”

Although several photos were included in Filo’s Pulitzer entry, the picture of the runaway over Miller’s body has been most remembered. The Pulitzer award lists Filo’s affiliations as The Valley Daily News and Daily Dispatch of Tarentum and New Kensington, Pennsylvania, a combined newspaper that developed Filo’s photos and helped send them over the wires. He says he took his film there as opposed to a larger publication because he had interned at the paper since high school and trusted the editors.

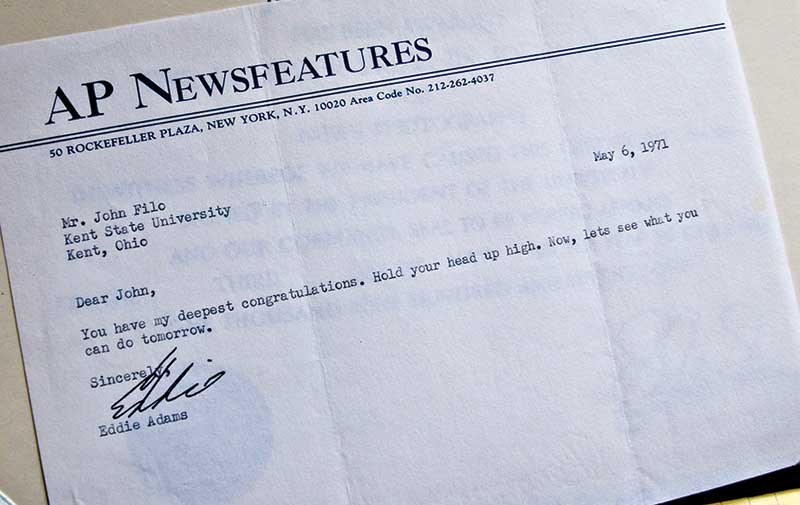

“I felt cocky for about two days,” says Filo about winning the Pulitzer. Then he received a letter from another Prize-winning photographer, Eddie Adams. It read: “Dear John, You have my deepest congratulations. Hold your head up high. Now, let’s see what you can do tomorrow.”

He remains one of the youngest people to win a Pulitzer, and one of the few students. He learned he had won by watching the news come over the wire machine in the Kent State journalism building, just feet from where he took his winning picture.

“I felt cocky for about two days,” he says. Then he received a congratulatory letter from mentor and Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Eddie Adams, who wrote: “Now, let’s see what you can do tomorrow.”

Filo says that for years he felt “very fortunate and very guilty” about the shootings, particularly when he considered the trajectory of the bullets. “An arm’s length to my right, a guy was shot. An arm’s length or two to my left, that’s where Jeffrey Miller was shot. I got this photo and I’m alive and it’s relatively famous. They are dead or wounded. We’re talking a few feet, either way. The randomness is what drives you crazy.”

The fallout from the shootings has been a messy mixed bag of government inquiries, court actions, and weak apologies. President Nixon’s Commission on Campus Unrest concluded the shootings were “unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable.” The guardsmen testified that they fired in self-defense, and criminal charges against them were dropped. A civil suit was settled for $675,000, with the soldiers offering tepid words of regret but no admission of wrongdoing.

The university, however, has come to terms with the event. A massive granite memorial resembling four caskets now stands near the shooting site. You can no longer park where the students fell. A visitors’ center and walking tour with trail markers are compelling and comprehensive.

Forty-four years after Filo took his picture, in Chicago, the city where I work, a white police officer shot a 17-year-old African-American, Laquan McDonald, 16 times, killing him. The city portrayed the shooting as an act of self-defense but refused to release a police dashboard camera video of the event. Only after 13 months, a public outcry, and a court order did authorities release the footage, which contradicted the official narrative. Just hours before the footage was made public, the officer was charged with first-degree murder. The teenager became a symbol of police brutality.

In many ways, Filo’s photo prefigures the McDonald video and other dramatic images of police violence that have captured the nation’s attention in recent years. Filo’s picture and the Kent State shootings have become vivid symbols of oppression. But the photo also represents hope and truth.

“That photo screamed for justice,” says Dean Kahler, who was shot by the guardsmen and paralyzed from the waist down.

Filo agrees. “You really couldn’t deny the photo,” he says. “That’s what it boils down to.”

In 2007, while working on an investigative series about unsafe toys, the Chicago Tribune rented a device that screens objects for lead. It looked, Sam Roe says, like “a pricing gun on steroids.” Roe took the device home and headed downstairs to his 3-year-old twins’ basement playroom. He held the gun against trucks, balls, and other toys, reading lead levels and jotting down notes.

Among his targets were plush Baby Einstein blocks decorated with vinyl ducks and other animals. The testing gun suggested a high lead level. Extensive lab analysis showed the vinyl affixed to the blocks contained hazardous amounts of the toxic metal.

The work of six reporters on two continents, the Tribune series led retailers and manufacturers to pull popular toys from shelves and sparked an overhaul of the US Consumer Product Safety Commission. The Prize was announced in April 2008, four months after Sam Zell bought the Tribune’s parent company, at a time when the paper was in turmoil. “The Pulitzer provided a bit of sanity amidst the chaos,” Roe says. “When you get down to it, it’s you, your phone, your documents, and your computer. If you can just put blinders on and ignore the distractions, you can do great work.”

He still keeps several yellow Baby Einstein blocks on his desk as a reminder.

Sam Roe is an investigative reporter at The Chicago Tribune. A Pulitzer Prize winner and three-time Pulitzer finalist, he most recently collaborated with data scientists at Columbia University Medical Center to uncover prescription drug combinations that are linked to a serious heart condition.