The presidential debate on September 29, 2020, ended with President Trump reiterating the false claim that mail-in ballots were subject to mass election fraud and citing this concern in order to justify his refusal to commit to accepting the results of the election should he be defeated. That assertion capped a six-month-long disinformation campaign, waged by the president as well as his party, against the expansion of mail-in voting during the covid-19 pandemic. That campaign has succeeded: polls conducted by Pew, Monmouth, and Morning Consult in August and September show that about half of Republican voters consider fraud a major problem with voting by mail, and more than half point to Democrats as the most likely perpetrators of election interference. Democrats, by contrast, overwhelmingly believe that mail-in voting is reasonably secure and should be used to increase access to the ballot during the pandemic. The consensus of both academic and independent journalistic investigations is that voter fraud is extremely rare and, where observed, occurs on a small scale unlikely to affect the outcome of a presidential election.

The gap between partisans regarding the susceptibility of mail-in voting to fraud is likely to affect voter participation in the election as well as perceptions of the legitimacy of the outcome. Voter participation may be depressed if Democrats are deterred from voting by mail because they fear that postal delays or allegations of fraud will nullify their vote; Republicans may shun mail-in ballots if they fear their votes will be stolen. Both may avoid voting at the polls if the pandemic surges in their precincts, although this is more likely to deter Democrats, who show a higher level of concern about infection. So long as the president declares that only a “rigged” election would explain his loss, the legitimacy of the results will be in question.

To understand how voting came to be so politicized this election cycle, my team at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard analyzed fifty-five thousand online media stories, five million tweets, and seventy-five thousand posts on public Facebook pages that referred to mail-in voting and the risk of fraud, all posted between March 1 and August 31 of this year. Contrary to most contemporary analyses of disinformation efforts in the American political-media ecosystem, our findings suggest that the disinformation campaign that has shaped the views of tens of millions of American voters did not originate in social media or via a Russian attack. Instead, it was led by Donald Trump and the Republican Party and amplified by some of the biggest media outlets in the country; social media played only a secondary, supportive role.

Donald Trump laid out his strategy around voting in a March 30 interview on Fox and Friends and again one week later in a tweet. In the interview, Trump bragged that he had forced Democrats to relinquish voting-related provisions, stating that their efforts to make voting easier and more ubiquitous during the pandemic would attract so many voters that “you’d never get a Republican elected in this country again.” One week later, Trump raised the matter again in a tweet:

Republicans should fight very hard when it comes to state wide mail-in voting. Democrats are clamoring for it. Tremendous potential for voter fraud, and for whatever reason, doesn’t work out well for Republicans. @foxandfriends

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 8, 2020

During the ensuing six months, the president and the Republican Party—abetted by major media outlets—executed on their strategy to discredit the voting process for millions of Americans.

Trump is the central node in the disinformation campaign

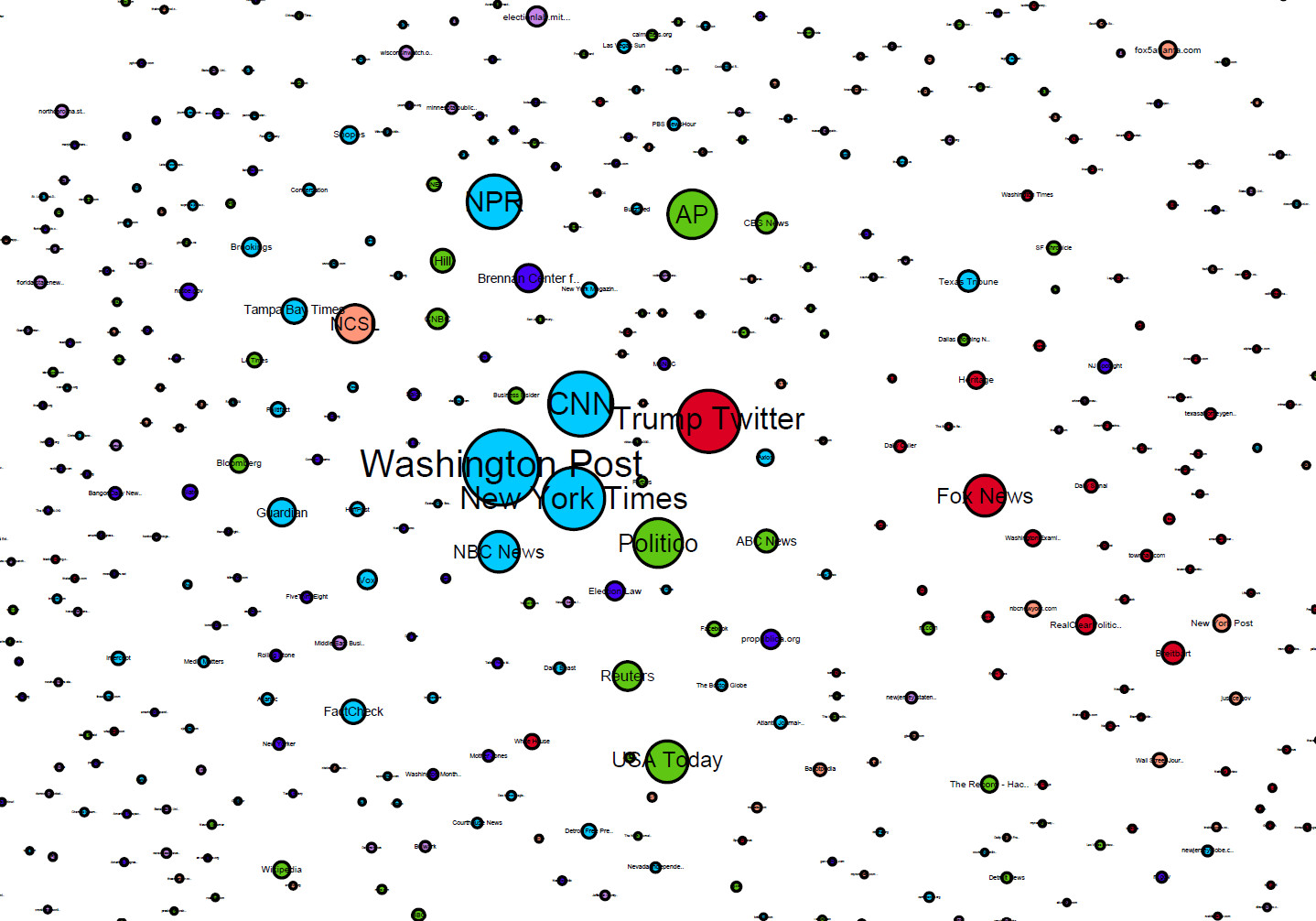

Figure 1 (below) shows a network map of media outlets that published the fifty-five thousand stories about the mail-in voter fraud frame and how they linked to one another. The map shows the by now well-known asymmetrical polarization of the American political-media ecosystem, with a distinct right-wing media sector and a “rest” of media that includes everyone from centrist services such as Reuters and the AP to left-oriented outlets such as MSNBC and Daily Kos.

The most prominent feature of the map is the central role that Trump’s Twitter handle plays in the media ecosystem, placing it on par with the most influential media sites—and, indeed, marking it as the most influential information source with a right-wing audience orientation. Trump’s Twitter handle is also the only right-wing-oriented site located firmly at the center of the map, indicating that it is influential for centrist and center-left as well as for right-wing media.

The centrality of Fox News to the right-wing media ecosystem also emerges clearly. More surprising, perhaps, is that “center right” outlets like the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post, which in most of our analyses are closer to the center, have been pulled deeper into the right-wing ecosystem, away from “the rest.” In the debates over mail-in voting and fraud, reporting in the Post and editorials in the Journal have boosted the legitimacy of the campaign, and are therefore highly linked to by right-wing sites. No left-oriented site plays a major role, with the exception of the Brennan Center for Justice—a nonprofit fighting voter suppression and the publisher of a widely linked literature review of studies of voter fraud in the United States.

The nodes are sized according to how many other sites link to their stories, which we take as a measure of influence among media producers. For this analysis, we created a synthetic source, “Trump Twitter,” which aggregates all links into tweets by @realDonaldTrump, the president’s Twitter handle. Node proximity is determined by the frequency of links: they are close to each other when either one of them links often to the other’s stories, and farther apart if neither links to the other often. The more central a node is in the map as a whole, the more influential it is for media across the ecosystem. Nodes take their color from the political orientation of their Twitter audiences, which we divide into quintiles: right (red), center-right (orange), center (green), center-left (light blue), and left (dark blue). Fox, which is both large and separate from the central cluster, is large because it is influential, and not central because its influence occupies a relatively insular subnetwork: the right-wing media ecosystem.

Figure 1: Media outlets that published stories related to the topic of mail-in voter fraud. Media outlets are sized and located according to interlinking among their Web stories on the topic. Trump Twitter plays a central role in the network. Fox News is central to the right. Notable is the large role that the AP, Reuters, NPR, USA Today, and the television networks play alongside the always leading sites of the New York Times, Washington Post, and CNN. (Click the image to open a high-resolution PDF.)

Political and media elites play a primary role in disinformation; social media plays a secondary role

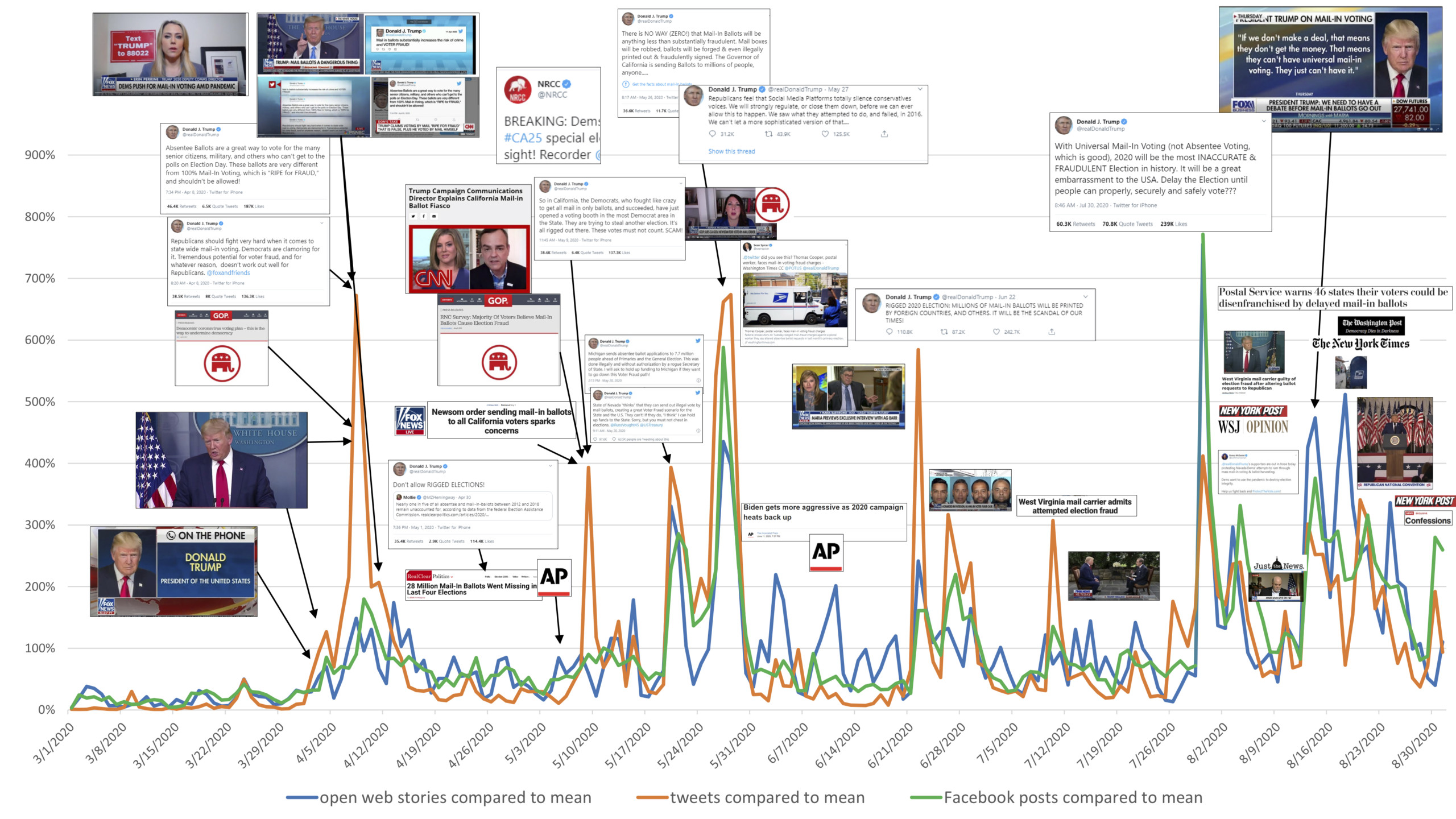

Figure 2 (below) shows the intensity of coverage of the mail-in voting fraud agenda across the fifty-five thousand stories, five million tweets, and seventy-five thousand Facebook posts we studied over the six-month period. Peaks in attention to the mail-in voter fraud frame on social media and in mass-media stories are clearly related. We studied every peak in attention from March 1 to August 31, looking at the Facebook posts with the greatest engagement, the tweets with the most retweets, and the earliest and most linked online stories across the political spectrum to analyze what statements, actions, or publications triggered each peak. In each case, the spike in attention was occasioned by a statement or action by a political figure or elite media outlet; the most common by far were statements Donald Trump made in one of his three main channels: Twitter, press briefings, and television interviews.

Many of these peaks aligned with, or were directly supported by, statements from Ronna McDaniel, chairwoman of the Republican National Committee; Trump’s communications staff, both at the White House and in his campaign; and, in one major spike, the president’s reassertion of the voter-fraud falsehoods at the Republican National Convention. Only one major peak was triggered by reporting in the Washington Post and the New York Times, about how changes to the Postal Service were causing delays in mail delivery; still, even that peak followed just three days after Trump’s August 13 phone interview with Maria Bartiromo on Fox Business, in which the president said he was refusing to reach agreement with House Democrats over coronavirus relief funding. (“If we don’t make a deal,” he remarked during that interview, “that means they don’t get the money. That means they can’t have universal mail-in voting. They just can’t have it.”) Several less prominent peaks in attention—following specific AP reports and instances involving news of a voter-fraud prosecution or guilty plea—generated coverage that received substantial attention on right-wing media and from right-wing politicians and media personalities.

What this means is that the “usual suspects” in public debates about disinformation are not the central actors in voting disinformation. We found no examples where clickbait factories, fake pages (Russian or otherwise), or Facebook’s algorithms could explain any peak in engagement that was not better explained as having been set in motion and heavily promoted by political figures and elite right-wing media personalities, and disseminated to millions by major media outlets. On Twitter, if bots or trolls played any role, it was dwarfed by tweets from the president, his staff, and other institutional and media allies.

Figure 2: Relative changes in the number of stories published online, tweets, and Facebook posts that mention mail-in voting or absentee balloting and fraud or election rigging, March 1 to August 31, 2020. Icons represent the precipitating event for each peak. Trump—using Twitter, press briefings, and television interviews—along with the RNC and his own reelection campaign, drives almost all peaks in attention. (Click the image to open a high-resolution PDF.)

Our data cannot exclude the possibility that targeted ads or narrowcast campaigns on Facebook, aimed to suppress carefully selected audiences, will affect voting in specific groups. Nor does it deny that radicals can use Facebook to organize for violence. These remain valid concerns about abuses of social media platforms. But our data strongly questions whether Facebook or Twitter has any meaningful role as an instigator of the broad suspicion with which Republicans regard mail-in voting, a notion that runs counter to the current criticisms of the social media platforms as the core purveyors of disinformation and the origin of mistrust in facts and institutions.

In this disinformation campaign, social media plays a decidedly secondary and supporting role. The disinformation campaign itself is elite-driven and transmitted primarily through mass media, including outlets on the center-left and in the mainstream.

News editors in mainstream media, particularly at the Associated Press and other sources of syndicated news, are a critical bulwark

There is a profound disconnect between the broad public concern with social media disinformation, the persistent scientific evidence that exposure to online fake news is concentrated in a tiny minority of users, and survey evidence that repeatedly shows that less than 20 percent of US respondents say they rely on social media as a major source of political news. Network and local TV, by contrast, are the primary source of political news for about 30 percent of the population, and news websites or apps accounted for another 25 percent, according to the most recent Pew survey. When arranged according to the degree to which they report believing mail-in voter fraud is a major problem, adults who get their news from ABC, CBS, and NBC occupy an intermediate position between Fox News viewers, on one end, and readers of the New York Times, viewers of MSNBC, or NPR listeners, on the other. Local TV news viewers, in turn, form the least politically knowledgeable group of Americans, edging out the much younger respondents who mostly rely on social media. When we analyzed the stories about mail-in voter fraud, we observed that peaks in media coverage usually consisted of large numbers of syndicated stories reported by the online sites of local papers and television stations.

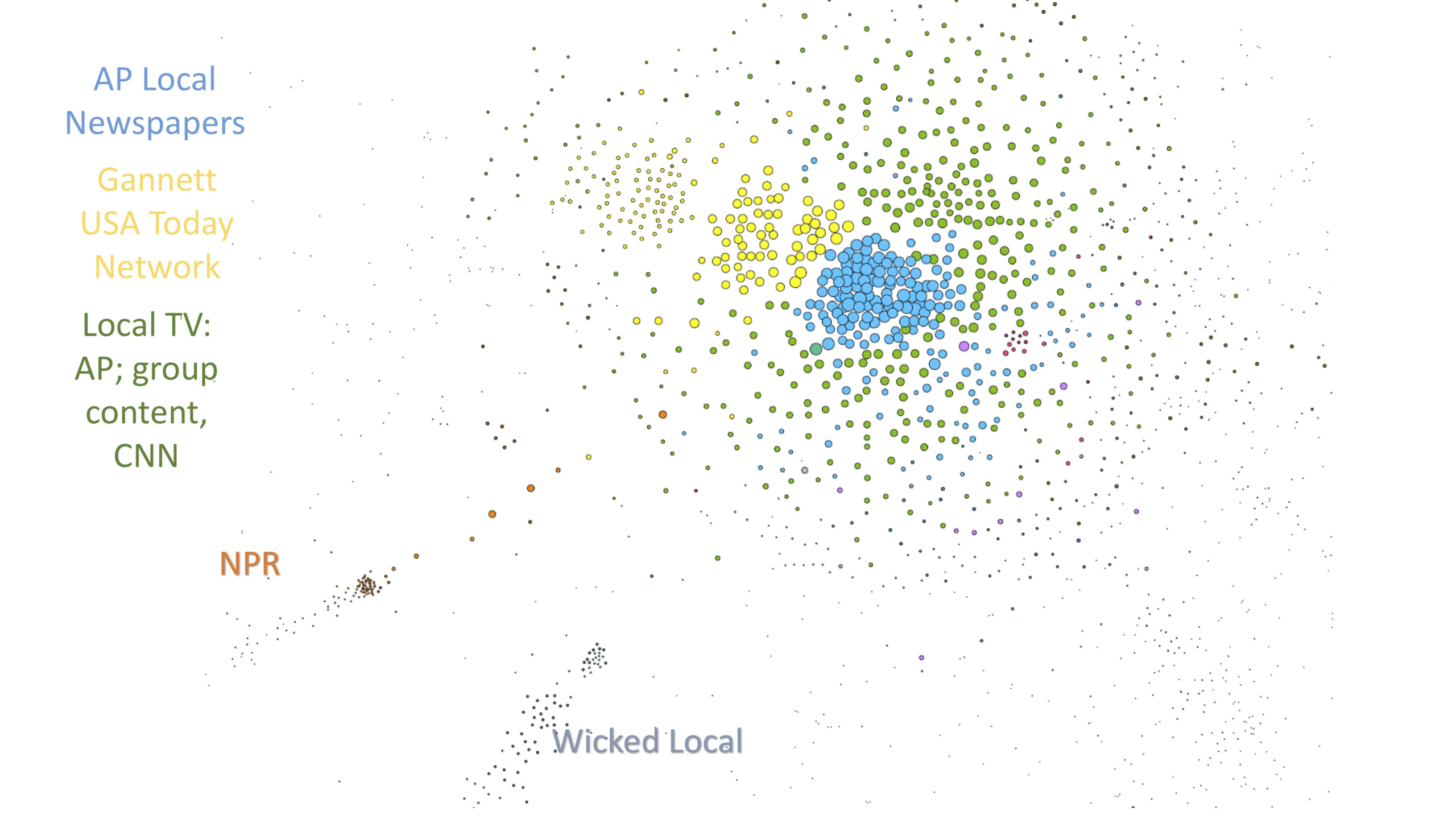

When we consider the listenership, viewership, and readership of these outlets, Figure 3 (below) offers insight into the central role syndication—particularly by the AP (which appears in both the blue and green clusters)—plays in shaping Americans’ perspectives. For news sites, the analysis looks directly at what these outlets publish. For local TV stations, the online news items offer only a rough image of what airs on TV; still, it is not unreasonable to assume that news items published online offer some insight into what the station will choose to air.

Figure 3 is a map of only those sites that republish stories that have duplicates in other publications. Each node represents a single media outlet. The nodes are sized according to the number of syndicated stories they publish. The links between the nodes reflect the number of times any two nodes syndicate the same story. Two nodes that often publish the same syndicated stories—for instance, local newspapers that syndicate the same AP stories—will be closer to each other, and farther away from a different pair of nodes that publish different syndicated stories: for instance, two NPR affiliates that often publish the same transcripts from Morning Edition, but not AP stories.

The color of the nodes reflects their membership in a network community identified by running Louvain community detection, the most widely used approach for identifying clusters of related sites in a network. The blue community at the center consists primarily of Associated Press syndication by local newspapers, some local television sites, and national sites. The yellow community reflects primarily local media that are part of Gannett’s USA Today Network, replicating USA Today stories but also reflecting some AP syndication. The green community consists mostly of local television stations, syndicating a combination of AP materials, CNN reports, and shared stories in group-owned stations such as Nexstar or Hearst Communications. NPR is visible in orange at the bottom left. The gray cluster nearby comprises Wicked Local publications. Given survey responses that suggest significant audiences (particularly those with low political knowledge) depend on local television, and the relatively high trust that survey respondents place in local media, the role of the producers of syndicated news and the editors of local outlets that use them becomes clear.

Figure 3: Map of sites that republish syndicated stories. Nodes are sized according to the number of syndicated stories they publish. Links are measured according to co-publication of the same syndicated stories. Color by Louvain community detection. (Click image to open a high-resolution PDF.)

Based on the survey evidence and the prominence of the number of stories they publish at peak moments of attention to mail-in voter fraud, no group of journalists and editors has a more important role to play in the month leading up to the 2020 election, and in the weeks and months thereafter, than those who work for syndicated news outlets. Given the insularity of the right-wing media ecosystem, it is extremely unlikely that viewers of Fox News or talk radio listeners will change their view that mail-in voting is an invitation for fraud. The equally confident responses of the readers of the New York Times or the Washington Post, NPR listeners, and MSNBC viewers suggest that they, too, will not suddenly begin to believe that Democrats are stealing the election by committing voter fraud with mail-in ballots.

But 30 percent or more of the US adult population is less committed politically, and less uniformly committed to one or the other proposition, regarding fraud and mail-in ballots. These people watch the TV networks, CNN, and local TV, and they trust their local media. That local media, in turn, depends on syndicated news. And it is these journalists and editors who appear to have been the most susceptible to Trump’s tactics of harnessing professional journalism to his disinformation campaign. Early in the campaign we saw more of the “balanced” approach that repeated the president’s framing of the problem as a partisan conflict. By August, more of the stories, including syndicated ones, underscored the falsity of the president’s assertions in either the headline or the lede, and even briefly reminded readers of Trump’s specific electoral strategy that leads him to make these false claims.

In the coming months, it will be critical for editors of these national and local media—trusted by the least politically pre-committed and, in some cases, least politically attentive citizens—not to fall for the strategy that the president has used so skillfully in the past six months. They should not capitulate to the inevitable charges of partisanship that will befall any journalist or editor who calls a disinformation campaign by its name. They should not add confusion and uncertainty for their readers, viewers, and listeners by emphasizing false equivalents or diverting attention to exotic but (according to our research) peripheral actors like Facebook clickbait artists or Russian trolls.

This article is based on a report by Yochai Benkler, Casey Tilton, Bruce Etling, Hal Roberts, Justin Clark, Rob Faris, Jonas Kaiser, and Carolyn Schmitt, Mail-in Voter Fraud: Anatomy of a Disinformation Campaign, Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society, Harvard University. October 2, 2020. Funding was provided by Craig Newmark Philanthropies, the Ford Foundation, and the Open Society Foundations.

THE MEDIA TODAY: Questions without answers in Trump’s covid diagnosis

Yochai Benkler is a professor at Harvard Law School and codirector of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard (BKC). This piece was cowritten with Robert Faris, research director at BKC; Hal Roberts, a fellow at BKC and technical lead of Media Cloud; and Ethan Zuckerman, director of the MIT Center for Civic Media.