On the morning of October 1, 1975, I was taking my turn at the cooperative nursery school my son attended when the pressmen—the workers who ran the physical presses—struck at The Washington Post. They did not go peacefully. Infamously, and painfully, they set presses on fire in the basement of the Post building and beat up a foreman. The Post would make the most of this, and it would divide and almost destroy the union to which I belonged, the Newspaper Guild.

Recently, I’ve observed a resurgence of interest in union organizing among young journalists who, amid rounds of unexpected layoffs, are feeling suddenly vulnerable. The newfound enthusiasm for solidarity against management is a welcome development, after decades in which many self-important journalists derided such activism as beneath them and unnecessary.

But there is a growing recognition now, that solidarity “almost forever” is not adequate in the face of hedge funds eviscerating newspapers and online news moguls facing economic headwinds.

Typically, bosses seek to portray unions as a third party interfering in the cordial, mutually beneficial relations between management and labor—an outside force. When members aren’t paying attention and don’t think they need to, that may be the case. This is what happened at the Post more than 40 years ago. Fresh off the glory road that led us to Watergate and the resignation of a president, we were suddenly internally imperiled. Smug in the newsroom, we paid little attention to the union-management battles raging in the floors below, where the printers and pressmen toiled. Our own local leadership (of the Washington-Baltimore Newspaper Guild, Local 35) was in the loop. But the 800 editorial and commercial employees the Guild represented at the Post weren’t.

ICYMI: We tested paywalls at NYTimes, WSJ & WaPo and more. All of them were pretty leaky, except one.

So, uninformed and in shock, Guild members met that October afternoon at the historic Metropolitan AME Church, around the corner from the Post. The unit voted overwhelmingly to cross the picket line and continue working. We would be the only one of several unions at the Post to do so during the pressmen’s strike. Our refusal to honor the picket line may have doomed their strike from the start. But we had already “withheld our excellence” minus a picket line the year before, so that the printers could continue working without jeopardizing their lifetime job guarantees. The paper published, our absence barely noted by readers and advertisers, and, after 14 days, defeated and humiliated, we went back to work.

A union, I was to learn, is only as good as its members and the time and effort they invest to ensure it represents their interests. At the Post, we had a “union security” clause, which meant that eight of ten covered employees had to belong or pay dues. In one sense, that made the union strong. On the other hand, it allowed union leadership to become remote from those it represented, and vice versa.

When the pressmen struck and the craft unions supported them, our local presumed that Guild-represented employees would, too. There may have been good reasons to show solidarity with the pressmen and honor their lines. But the angry mandate from our local leadership to stay out, coupled with the violent start to the pressmen’s strike, dominated our debates. In that first meeting, I voted to cross.

A second vote a few days later brought the same result. This time, deciding our long-term interests were better served by joining the strike, I switched sides, voting to honor the picket lines. But I felt bound by the unit majority and not by local commands. A few of us inside the newsroom published leaflets in support of the strikers. Other newsroom employees chose to honor the picket line. With growing pressure from within and without, my Guild unit scheduled a third, critical vote, which was much closer but ultimately yielded the same outcome. Again, I sided with the strikers.

In December, Katharine Graham, the Post’s publisher, delivered her final offer, which she fully expected the pressmen would refuse. They did. Things got ugly. A pressman’s picket sign declared “Phil Shot the Wrong Graham,” a reference to the suicide of Katharine Graham’s husband that had propelled her into the publisher’s post. Graham proceeded to hire “replacement” workers. Then, the pressmen’s union busted, one of its members ended his life.

Our local, meanwhile, had filed charges against Guild members, including me, who had continued to work. Hastily, we hired lawyers to defend us. The international guild, fearing the loss of its then-flagship Washington Post unit, defended the accused, and the National Labor Relations Board dismissed the charges.

RELATED: A law firm in the trenches against media unions

In the wake of all this conflict, our Guild contract lapsed, hundreds quit the union, and an “independent” union arose to challenge Guild representation. I found myself embattled on two fronts, fighting against our local, but for the Guild, and against what we perceived as an upstart company union. Bitterness reigned.

The Guild prevailed in the representation election, but it was a Pyrrhic victory. Without the “union security” provided for in our lapsed contract, nobody had to join or rejoin or pay dues. The shrunken unit was in shambles and still at war with most of the local’s other units, which had supported the pressmen, and with our distant local leadership, including a charismatic chief administrative officer who had been forced to step down but whose replacement was also unacceptable.

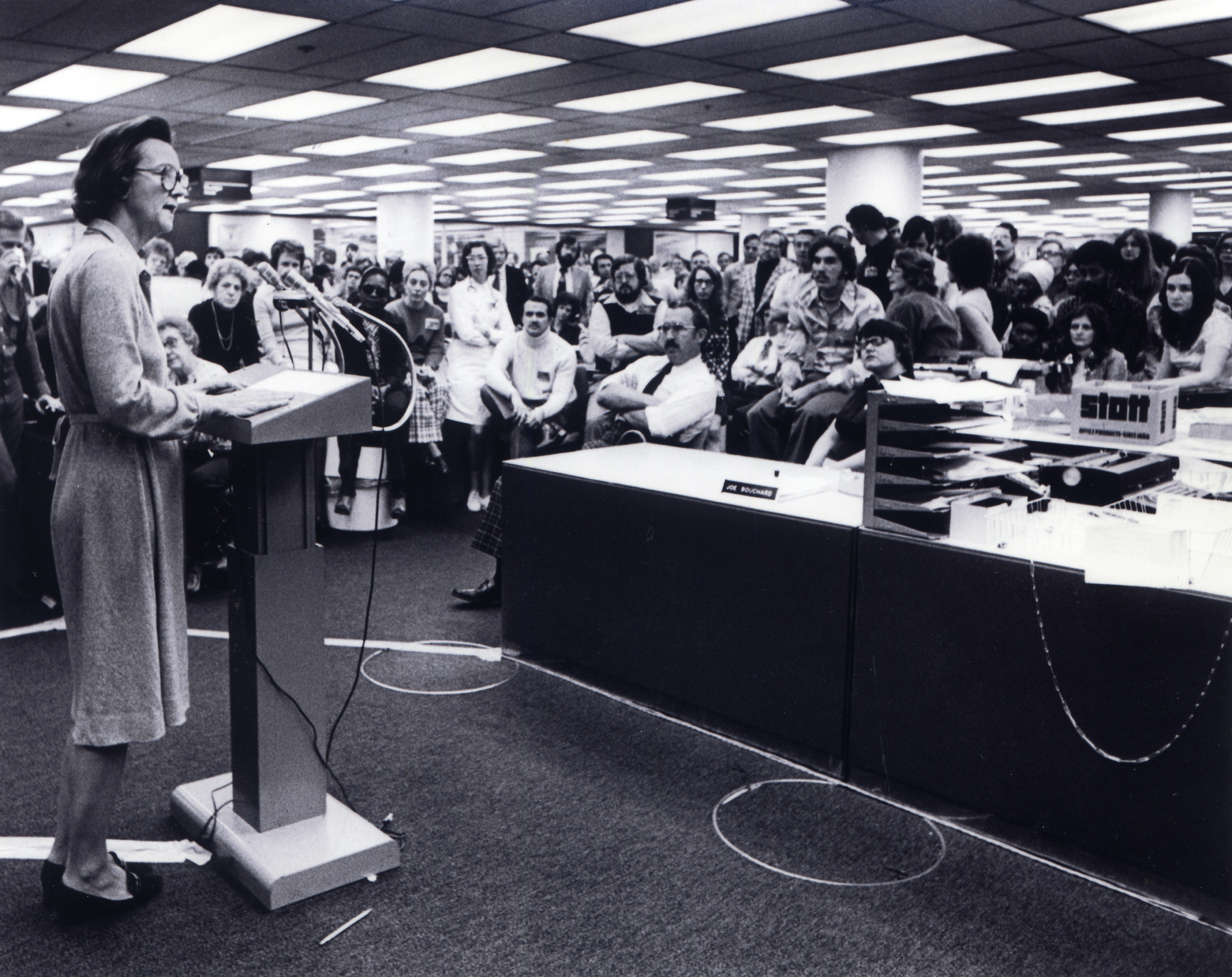

Through the wreckage, I somehow emerged, somewhat reluctantly, in 1978 as the chairperson of the Post Guild Unit. Our contract had expired in the spring of 1976, and, despite retaining union representation, we were struggling to survive. The company had ceased to observe past practices, such as the automatic deduction from paychecks of union dues–the lifeblood of the organization. For new and returning members, we had to hand-collect dues.

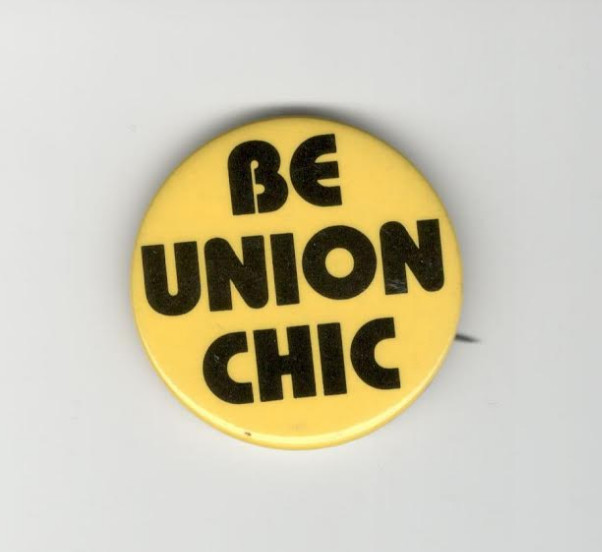

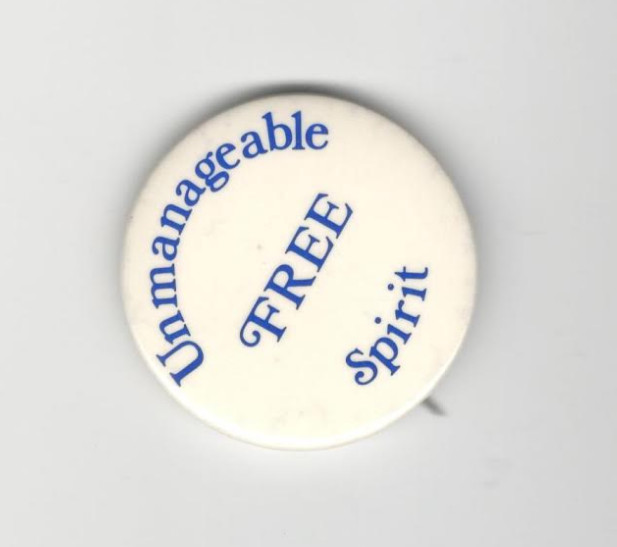

A comment from Executive Editor Ben Bradlee inspired a button, “Be Union Chic,” as did a note from management saying that it couldn’t abide a newsroom full of “unmanageable free spirits.”

We were down but not out. I reasoned, Let’s at least have some fun. Our antics included a Washington Post Guild Unit Film Festival (W.P. G.U.F.F.) and a rally in front of the building with bluegrass music and a telegram from actor Ed Asner, who’d played the crusty newspaper editor Lou Grant in a popular television series. Morton Mintz, a legendary investigative reporter, wrote a three-part series of bulletins titled “The Fruits of Your Labor,” a deep dive into company finances.

Slowly but surely, resigned members started to rejoin, and I would tout by name the “new and returning members” in my weekly bulletins. If Israel’s Begin and Egypt’s Sadat could reach a peace agreement, wrote Pentagon reporter George Wilson, inspired by our efforts to join after 11 years with the Post, then surely the Post and Guild could resolve their differences. Washington Journalism Review hailed the Guild’s “Lazarus-like resurrection.” Yet, despite our efforts, negotiations dragged on.

Hoping to break the impasse, Donald Graham (Katharine’s son, then executive vice-president and publisher heir apparent) and I had several sidebar meetings—breakfast at the historic Mayflower Hotel, dinner at the Roma, a neighborhood restaurant, on upper Connecticut Avenue NW. Our tentative agreement called for a five-year contract, non-contractual raises rolled into the pay scales, a form of union security and dues checkoff. I was bargaining with the approval of my committee and our chief negotiator, international rep Bill Blatz, an old union warhorse who subscribed to the Samuel Gompers philosophy: “What does labor want? We want more…”

I was feeling optimistic. But Blatz objected and the bargaining committee rejected the deal.

Today, the Guild Unit at the Post is facing much less agreeable management in Jeff Bezos.

But unit leadership became increasingly frustrated with Blatz, whom some members felt was more concerned with the international’s institutional interests than with ours. We demanded a new chief bargainer and settled a contract, in 1979, for far less than Graham and I had agreed to the year before. Preceding the digital revolution in the news business, this was certainly a pivotal moment in the industry—for both labor as losers and management as winners.

Today, the Guild Unit at the Post is facing much less agreeable management in Jeff Bezos, whose representatives demanded many more concessions than the paper had under the Graham family. Yet the local, now in friendlier hands, continues to file grievances on behalf of unfairly treated employees and to attempt to improve wages and working conditions.

If we had been paying attention before the pressmen’s strike in the 1970s, I’m convinced the Guild at the Post today would be dealing with a stronger hand. That’s the hard-learned lesson I hope the new generation of journalist union activists will take to heart.

So, welcome aboard, workers of Vice, Vox Media, New York magazine, The New Republic, Slate, the Onion, Group Nine Media, and Refinery29. You may think of yourselves as professionals, and of course do strive to maintain high professional standards. But, in the world of economic realities, you are commodities. You are workers. Wear that label with pride. Or, as I used to write at the end of my union bulletins: Join the Guild. You can’t afford not to.

RELATED: Five union members from across the Rust Belt reflect on eroding faith in the media

Eugene L. Meyer is a former longtime Washington Post reporter and editor and an author. He is the editor of the quarterly B'nai B'rith Magazine. His most recent book is Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown's Army.