Today’s digital outlets have made identity issues—on race, gender, and sexuality—core to their reporting.

BuzzFeed has a robust LGBT section, a Latino coverage editor, and hosted a recent Black History Month series. Fusion is a joint venture between Disney-ABC and Spanish language network Univision, which the site says targets a “young, diverse, and inclusive millennial generation,” and has a ‘justice’ vertical focused on these topics. The Atlantic, home to Ta-Nehisi Coates, a marquee writer on black America, led its site last week with a story on “The Sexism of Startup Land.” One of Vox’s most-read pieces last week was “Reaction to the Oklahoma frat scandal shows just how poorly Americans understand racism.”

“News stories that used to be considered in some way niche—marriage, immigration, and conflict between police and black communities—are perhaps the three biggest domestic stories of the last three years, whatever the audience,” Ben Smith, editor in chief of BuzzFeed, wrote last month. And while recent events have thrust diversity issues into public debate, the surge in coverage goes beyond news: Offworld launched last Monday, a website for video games writing by women and minorities; ESPN’s upcoming The Undefeated covers the intersection of diversity and sports.

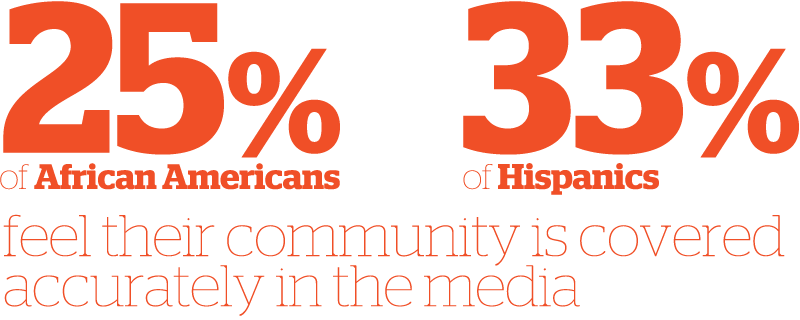

Digital media has played a major part in the well overdue corrective in covering historically underrepresented groups. An American Press Institute survey last year showed only 25 percent of African Americans and 33 percent of Hispanics felt their community was covered accurately in the media, with mainstream publications having long vacillated on how to approach minority coverage. The New York Times, for example, created a high-profile race beat in 2014—just as they once had in the 1970s and ‘80s—then shuttered it a year later.

For newer outlets, areas like LGBT issues—not a traditional beat at legacy newspapers—are baked into the organizational hierarchy. “It’s really just the luxury of building a newsroom from scratch,” said BuzzFeed’s Smith in an interview. “I bridle at the sense that these are niche topics we’re choosing to cover.”

At the same time, Web writing prioritizes a punchy “voice” more than legacy media. “Online organizations can have stronger points of view than most legacy news organizations within the parameters of what they’re calling news. So I think that appeals to people who have passionate feelings about conflicts,” said Wayne Svoboda, a CUNY journalism school professor who teaches conflict reporting.

“It’s a market differentiation technique,” he added. “There’s no real reason, in terms of a business model, to go online and recreate what already exists.”

Indeed, it would go against demographic trends to recreate legacy structures online—tying all these online outlets’ coverage together is both a culture shift in their readership and an adaptation to the way stories are consumed online.

Online organizations can have stronger points of view than most legacy news organizations within the parameters of what they’re calling news. So I think that appeals to people who have passionate feelings about conflicts.

The audience for these sites are, largely, millennials: a younger generation than readers of legacy media, and one that advertisers want a slice of—they’re due to spend $200 billion annually by 2017, explaining the vast capital invested in outlets like Vice, now valued at $2.5 billion. Millennials are on track to overtake baby boomers this year as the largest living generation, and are both more liberal and racially diverse, with 43 percent non-white (including Hispanics), according to the Pew Research Center. Their appetite for diversity coverage is strong: Rinku Sen, publisher of Colorlines, which has specifically covered race since 1998, said its core readership shifted 15 years younger, to 20-35, after they moved from a bimonthly magazine to online-only in 2010. At that point, “our traffic and readership blew up,” she said, as a topic once considered a niche supplement to newspapers and magazines became a well-read source in its own right. For BuzzFeed, whose core readership is between 18 and 35 according to Smith, race and women’s issues form a large chunk of content but are not segregated into their own verticals (LGBT has its own section).

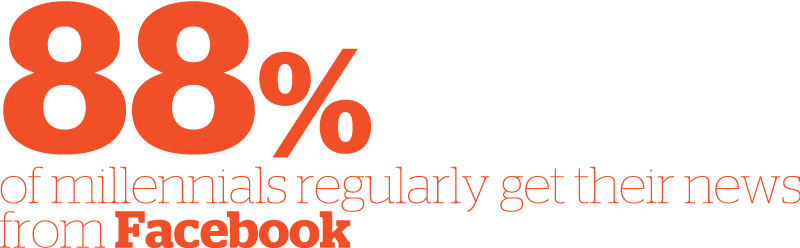

Especially when targeting a social media-savvy young population, social networks and identity politics stories play to each other’s strengths. A recent American Press Institute and AP-NORC Center survey showed 88 percent of millennials get their news from Facebook regularly. And Twitter and Facebook are where minority groups specifically coalesce to critique mainstream media coverage of their communities, share stories from their own points of view or whip up support for a common cause—see, for instance the hashtag activism of #AskHerMore or #NotYourAsianSidekick.

“I think of social media, in a way, as counter-programming to the kind of stories that mainstream media frames,” said Jose Antonio Vargas, the journalist and famously undocumented immigrant who is launching #EmergingUS, an immigration, race, and identity site with The Los Angeles Times this spring. “For me one of the greatest challenges and opportunities facing journalism right now is who’s telling whose story and who’s framing whose narrative.”

The centrality of social media to diversity coverage fits online news outlets like BuzzFeed, which is institutionally organized around distributing their content on the social Web. They wish to target social media audiences, and identity issues are a reliable way to do that. Shares can create a virtuous circle too: They are a valuable signal to editors about how much previously marginalized people care about these stories, encouraging more coverage.

But the internet is also about self-representation and identities built through social media. The articles people retweet or share are statements on their viewpoints and identity. Thus, when a reader—regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation—is irked that female actresses are only receiving questions about their shoes at the Oscars, or outraged at the Ferguson police department, they share a story about it—probably by a writer who expresses what they want to say, but better. Even if the reader feels the exact opposite of what the author is saying, they might still hate-share the story with a snarky remark.

“People see the content that they post as a form of self expression,” said Sen.

The risk to thoughtful coverage of minority issues and structural inequalities is that if journalism is used as a badge of identity and little more, publications may prioritize aligning their politics with their readers, making for homogenous reporting, said Fredrik deBoer, a PhD candidate at Purdue University who blogs frequently on media and education. “You want to signal to people that you are part of this newer generation, that you’re hip and that you’re young,” he said.

Digital media particularly dominates the “hot take” economy of online opinion writing. The recent viral video of a University of Oklahoma fraternity singing horrendously racist chants followed the usual course: a chorus of op-ed condemnation, with a few so outlandish they inspire their own backlash—in this case, MSNBC’s Mika Brzezinski suggesting rap music contributed to the incident, prompting the ironic hashtag #RapAlbumsThatCausedSlavery and yet more takes. Yet, as Vox also notes, putting the spotlight on isolated cases of blatant abuse says little about the deep roots of inequality. Instead, it pins the incident on the moral failings of individuals that the reader can safely distance themselves from.

Meanwhile, reported deep-dives that advance our understanding of prejudice, like The New York Times on the racial inequalities not just in, but around Ferguson, The Washington Post on the decline of black voters’ influence in the nation’s capital or ProPublica’s consistent investigations into housing discrimination, are not exclusive to “new” or “old” media.

Still, even when legacy media attempt to get on board with identity stories, they do it on the Web. When NPR decided to increase race and culture output, the result was a blog, Code Switch. Bloomberg, in the midst of a Web-centric rebranding, recently released a 3,400 word profile of undocumented immigrant-turned-Goldman Sachs vice president Julissa Arce. And at #EmergingUS, the LA Times’ new venture with Vargas, there is no mistake about what platform they are going to prioritize—the hashtag is in its very name.

Chris Ip is a CJR Delacorte Fellow. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisiptw.