It’s widely known but rarely acknowledged: Most news paywalls are full of holes.

Publishers aren’t just offering a few free articles per month. They’re building in sweeping exceptions that allow tech-savvy readers—and often simply those entering through search or social media—to access most or all of what subscribers pay for.

It’s easy to understand why subscription outlets want to keep people out. But, even as the so-called “Trump bump” drives up new subscriptions, many also see powerful reasons for letting a lot of people in: from promotion, to data collection, to greater impact on public discourse.

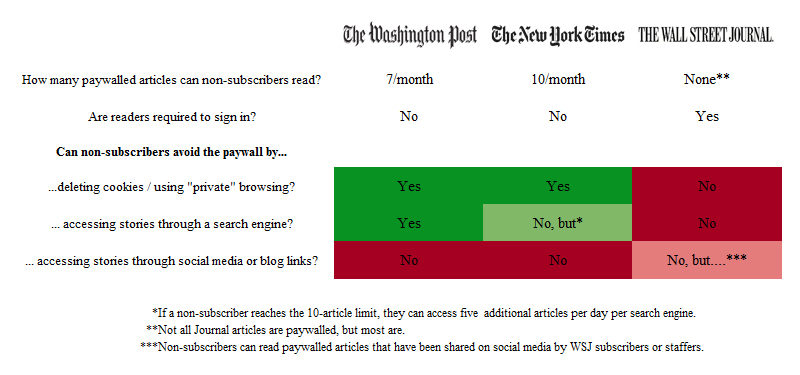

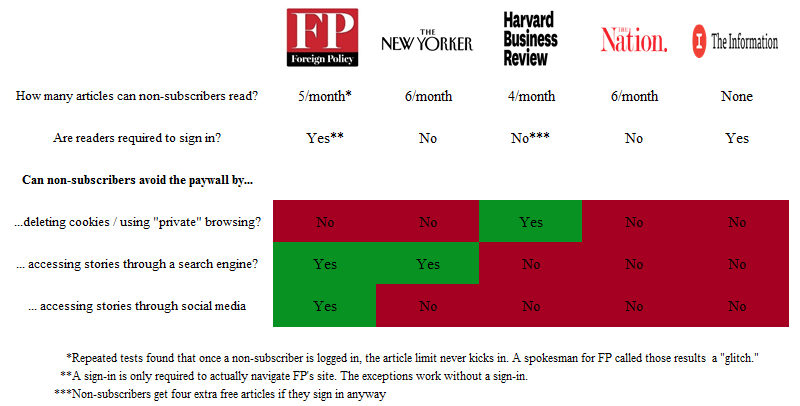

We tested the paywalls at eight prominent subscription news outlets, three daily newspapers and five magazines—The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The New Yorker, The Nation, Foreign Policy, Harvard Business Review, and The Information—and found that all but one of those were “soft” to one degree or another, and six of eight allowed for some form of unlimited exception, allowing non-subscribers to read widely.

Paywalls are more important to the news business than ever

Paywalls have been a part of online news since The Wall Street Journal’s launched in 1996. The Journal’s approach, from that time until last year, largely mimicked its print subscription model: the “hard” paywall, paying customers only.

The New York Times pioneered the alternative “soft,” or “leaky” model in 2011. It allowed non-subscribers to read 20 articles per month (since reduced to 10). And, it created mechanisms for unlimited access.

RELATED: Print is dead. Long live print.

The exceptions worked like this: When a reader arrived at a story through a search engine or by clicking a link on social media, that story wasn’t counted toward the free allotment. The meter would kick in only if the reader clicked on another article on the site.

Non-subscribers could also subvert the mechanism entirely by manipulating “cookie” files, a common marketing tracker stored on readers’ computers. Deleting cookies restarts the counter tracking how many stories a user has read, and the “private” mode built into most browsers prevents cookies from being saved in the first place.

In general, it’s the Times’s “soft” model, unlimited exceptions and all, that has prevailed.

Since then, paywalls have become much more common, and—with steep, long-term declines in print and digital display ad revenues across the industry— far greater contributors to publishers’ bottom lines.

Times2020, a planning document released by the publisher in January, identified the Times as a “subscription-first business.” Over the past year, digital subscriber numbers have shot up around the industry, a phenomenon referred to as the “Trump bump.” The Times added 755,000 new subscribers in the year ended on March 26, 2017, a 65 percent increase, according to its most recent quarterly report.

The Wall Street Journal signed up around 300,000 in roughly the same time period, representing growth of about 33 percent, Robert Thompson, CEO of the Journal’s corporate parent, said on an earnings call. Digital subscriptions now make up 53 percent of the subscriptions at the company, up from 38 percent just two years ago.

Overall, paywalls and paywall policies are more important for publishers than ever before. And, in general, it’s the Times’s “soft” model, unlimited exceptions and all, that has prevailed (see chart above).

Newspaper publishers see benefits to broad paywall exceptions

“It’s a misconception that we’ve imposed an absolute limit and any time anyone gets around that limit it’s a violation of policy,” says Kinsey Wilson, executive vice president for product and technology at the Times.

Kinsey said the paper aspires to build both a large subscriber base and massive web traffic, a dual approach that almost requires a porous paywall. Its site has about 2.2 million digital subscribers, more than any other news outlet. It received about 89 million unique visitors across all platforms in March, according to ComScore, the highest traffic among the outlets we tested (though still short of that of free news sites such as those of CNN and USA Today).

“We’re a general interest publication,“ says Wilson. “We need to create a great experience for subscribers, but we want a great experience for people who are consuming it lightly, too.”

He acknowledged that some people abused the workarounds to the paywall, but he largely writes them off. “These are extremes that are not generally a big business concern,” says Wilson. “We try to deal with 85 percent of human behavior.”

Among the paywalls we examined, the Times’s paywall was one of the softest. The paper offers more free stories than any other paywalled outlet. One of its three unlimited exceptions—for “private” browsing—is still intact in its original form.

Until recently, social media referrals to Times stories also didn’t count against the paywall total allowed. The paper quietly closed this loophole sometime after Wilson and I spoke. A spokesman said the change was meant to align the Times with its subscription-first strategy.

On search referrals, the Times’ new approach points to the nuance with which publishers treat these questions. The paywall no longer exempts stories reached by search from the 10-article limit. Once a reader hits the limit, the Times grants five additional search-accessed articles per day, or potentially around 150 per month, per search engine.

Exceptions to the exceptions.

True to its tradition, The Wall Street Journal’s paywall was the tightest of those we examined, at least among the daily newspapers. The Journal’s site places a small number of articles in front of the paywall, but offers no metered access to paywalled stories. It also makes no exceptions for search, and doesn’t rely on “cookies.”

“Who is your most valuable audience?” asks Karl Wells, vice president for sales and marketing at Dow Jones, the Journal’s parent company, in an interview with CJR. “Is it the people who are paying you, who are are sustaining the future of quality journalism? Or is the people coming to your site for free and not paying?”

Until last August, the Journal made no exception for social media, either. Then, it changed tack and introduced a unique, limited form of the exception.

The Journal’s paywall doesn’t exempt all social media traffic, as the Times’s once did. Instead, it lets in non-subscribers who click social media links shared by a Journal subscriber or staff member.

Wells explained the change as, among other things, an additional benefit of subscription. “Our members weren’t able to share stories with their friends on social media,” he says. “Now they can.”

But, he also acknowledged the ways the Journal benefits from allowing more people through, both in terms of promotion and the opportunity to collect information.

“We do a lot of data analytics and data science,” he says. “We look for what signals someone has to show before they subscribe?”

The larger audience boosts the Journal’s ad sales as well. And, Wells explains, the data collection enables the Journal to sell better-targeted and therefore more expensive ads.

He also cited broad reach as, to some extent, an end in itself, specifically highlighting the new social media exception for Journal staffers.

“We want to continue to have an influence and a say on issues out in the world,” he says. “The Journal has a voice, and on social that voice is very loud.”

Magazine make fewer exceptions, but “hard” paywalls are rare

On the magazine side, we found paywalls to be generally more restrictive than those of newspapers, but not by much.

Magazines offered fewer free articles than newspapers (though they also produce fewer). Three of the five outlets we examined require visitors to register an account before they can read, and the other two offered users incentives to register in the form of extra free articles.

RELATED: Inside (The) Information

They had fewer paywall exceptions overall, but three outlets—The New Yorker, Harvard Business Review, and Foreign Policy—had some version of the unlimited exception.

“There are always going to be tradeoffs,” says HBR’s deputy publisher, Sarah McConville. “We’re less worried about people deleting cookies and more worried about what people are looking at and what they’re doing. That’s a huge utility for us.”

She also pointed out that having a paywall with free articles and even wide exceptions still isn’t the same as giving everything away, echoing several other executives we spoke with.

“From the consumer’s side, people just don’t like paywalls,” she says. “That’s enough of a factor that, over time, people decide, ‘I’m tired of deleting my cookies or switching my browser.’”

Richard Kim, executive editor of The Nation, one of only two publications on our list that entirely shun paywall exceptions, explained the policy by citing his magazine’s narrow focus, its lack of reliance on advertising, and its passionate audience.

“We’re a niche publication. We do this high-level political analysis. We don’t write movie reviews or anything,” he says.

They’re not just trying to get access to content. They want us to exist. They see themselves as contributing to a cause.”

The Nation offers non-subscribers three articles per month, and three more if they register and sign up for a newsletter. And that’s it.

“The vast majority of people who come to the site read as much as they want,” Kim said, and never actually hit the article limit.

As for the subscribers, “They’re not just trying to get access to content. They want us to exist. They see themselves as contributing to a cause.”

A subscription is often more than a transaction

This impulse on the part of readers came up several times in our interviews.

“While we are a for-profit organization, we’re also a mission-driven organization, and, ultimately, family-owned,” says The New York Times’s Wilson. “That’s a big part of the philosophy behind the paywall.”

To the extent that that Times journalism is available for free to non-subscribers, and many people pay for it anyway, the model begins to resemble that of a different type of organization: public media or other nonprofits.

I suggested the comparison to Wilson. “I think there are similarities [to public media],” he says. “A subscription to TheNew York Times is rarely a purely transactional decision. But, we do set down a hard line.”

The Journal’s Wells, though, was having none of it: “Do we play on the ‘Give us a donation’ stuff? No.” he says. “If people want to subscribe because they want to contribute to the cause, then brilliant. We’re not going to turn them away. But it’s not something I’m going to write about on billboards all over New York. I think that’s kind of desperate, actually.”

Correction: This story has been updated with the correct year of the launch of The Wall Street Journal‘s paywall.

Ariel Stulberg is a writer and data analyst based in New York. He covers tech policy and the media business.