This is the first of a two-part series; for part two, click here.

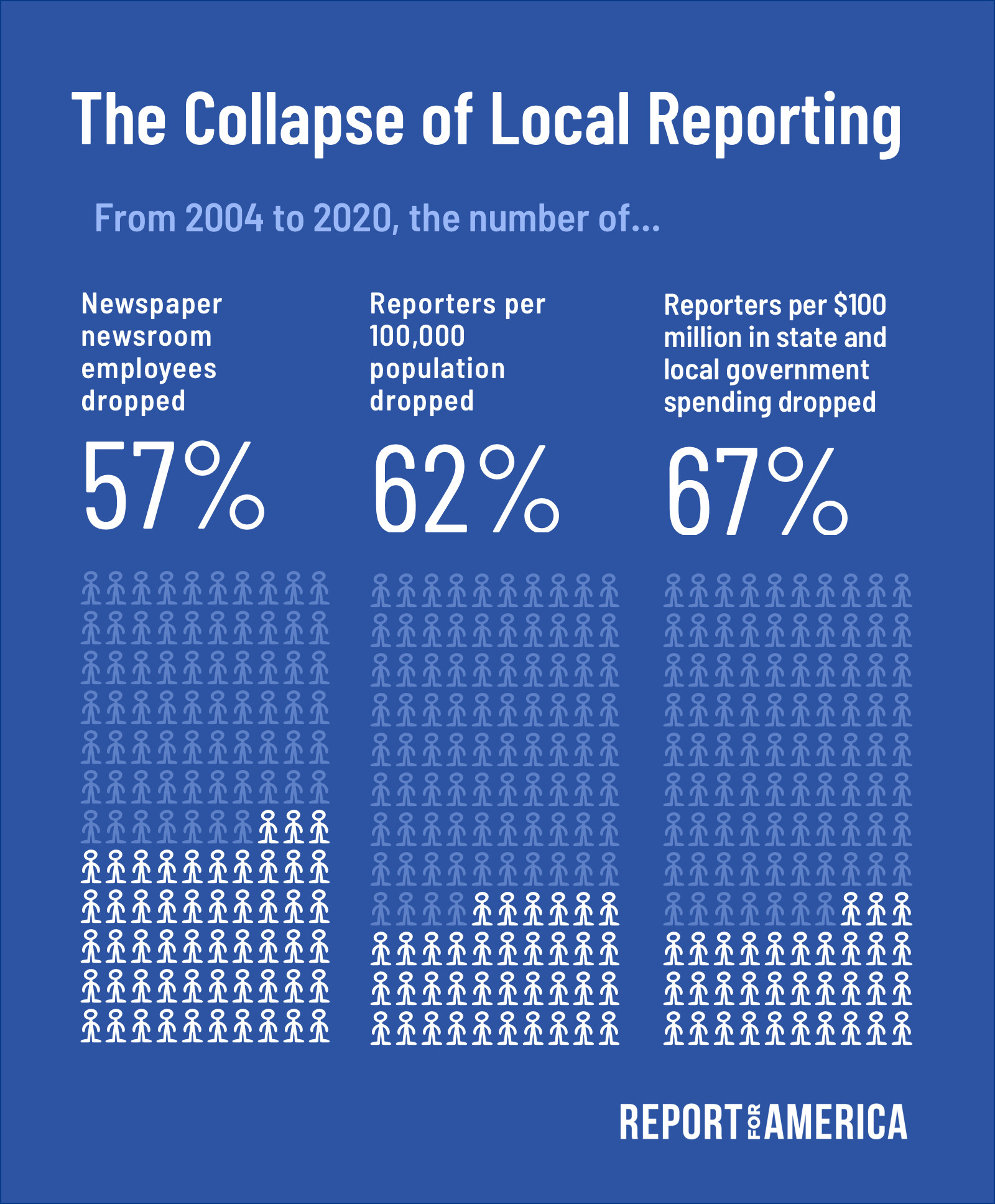

IN MEASURING THE COLLAPSE OF LOCAL NEWS, there is arguably no more important metric than the number of local reporters. Though precise numbers are hard to come by, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports an astounding 57 percent decline in newspaper newsroom employees—from 71,640 to 30,820—since 2004. Depressingly, academic studies show that the local news collapse has likely led to lower voter turnout and bond ratings, and more corruption, waste, air pollution, and corporate crime.

It is a truly bleak picture. And yet focusing exclusively on that employment statistic understates the problem, as becomes clear when we look at the decline in the context of four other factors: spending by state and local governments, population growth, the trajectory of other professions, and the rise of misinformation engines.

Courtesy of Report for America

Newsroom staff declines versus population

As reporting staffs have shrunk, the American population has grown. Since 2004, the number of newspaper newsroom staff per 100,000 people—a measure we might call “coverage density”—has dropped by a staggering 62 percent. This shows statistically what we knew anecdotally: reporters are spread far thinner than they used to be. It also helps explain the rise in “ghost newspapers,” more than 1,000 publications that have lost more than half of their staff in recent years.

…versus other professions

Maybe this per-population decline is not unique to journalism; maybe, instead, this is just a pervasive phenomenon across the economy as the population grows.

Alas, no. As the number of newspaper journalists per 100,000 people plummeted, the number of teachers-per-100,000 rose slightly, as did the number of nurses. Perhaps most relevant, the number of librarians per 100,000 has barely changed since 2000. According to the Institute for Museum and Library Services, there were 50,900 librarians and 143,888 library staff in 2019, the most recent year for which data was available. The same year, there were about 34,000 newspaper newsroom staffers, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Librarians and local reporters have two things in common: they’re in the information-providing business, and pundits predicted that the internet would make them obsolete. But, as with journalists, we need librarians, in part, to help people separate fact from fiction on the internet! Notably, the two fields differ in one important way: librarians have a sturdier business model (i.e., taxpayers).

…versus local government spending

Remember how less local news leads to more government waste? Consider this: from 2004 to 2020, as the number of reporters declined, the amount spent by state and local governments increased by 76 percent (or 29 percent, in constant dollars), fueled in part by growth of Medicaid and spending on police and corrections. In 2004, using real dollars, there were almost three reporters for every $100 million spent by state and local governments; in 2020, there was just one reporter per $100 million, a 67 percent decline.

State and local government spending comes through political units of all shapes and sizes—including municipal governments, townships, public-school systems, and special districts. In 2000, each local reporter on average covered 3.8 different units of government. In 2020, each reporter covered 10 units of government.

…versus misinformation engines

The collapse of local news has created information vacuums. These have not remained empty; rather, they’ve been filled by national news (cable, talk radio, national newspapers), global social media platforms, and, increasingly, local social media platforms. As a result, the decline of local news leads to more polarization—which, in turn, increases the spread of misinformation. Meanwhile, as CJR has documented, “pink slime” sites—some 1,400 and rising—have entered the void. They offer partisan content or pay-for-play advertorial content, neither of which is consistently labeled as such.

At the same time, Nextdoor and Facebook Local groups have grown. Nextdoor is now in 233,000 communities, reaching 53 million Americans (double the number it reached in 2018). In addition to connecting neighbors for all sorts of truly positive purposes, the service has become a major spreader of covid-19 misinformation, QAnon conspiracy theories, and other types of falsehood. Researchers have found similar problems with local Facebook groups. Some 75 percent of Americans said they encountered misinformation on Facebook, while only 16 percent said they did in their local newspaper, according to a Gallup/Knight Foundation survey. Both Nextdoor and Facebook recently announced steps they believe will minimize the odds of misinformation spreading among groups, but they’re going to need a lot of help from actual reporters.

Local reporting plays a critical role in combating misinformation; local reporters are more trusted, in part, because they’re on the ground and can interact with residents directly. Despite some early signs that fact-check websites backfired, the academic research now seems clear that fact-checking actually helps quite a lot, especially when reporters follow up and confront public officials. We need roughly a zillion more pieces with the tone and thoroughness of this locally informed covid-19 faq by Annie Berman, a Report for America corps member in Alaska.

We need to regain the number of reporters lost over the past two decades, and add an additional corps of local reporters who can help counter misinformation. But how many is enough? And how do we get there?

This is the first of a two-part series; the second part is available here.

Steve Waldman is President of Rebuild Local News and co-founder of Report for America.