Robert Lorton’s family owned the Tulsa World for a century before selling the newspaper to Warren Buffett’s BH Media Group in 2013. Lorton, the daily’s publisher for eight years, went to work at a bank, but he missed the family business. So in 2015 he founded The Frontier, a local news site devoted to enterprise and investigative reporting.

To avoid the advertising sinkhole, Lorton began by charging readers $30 a month for subscriptions and up to $5 for access to individual stories. “What we’re trying to sell is the value of having someone in your community being a watchdog,” he said in April 2016. He viewed going nonprofit as a back-up plan, but was determined to try the for-profit model first.

Seven months later, Lorton opted for Plan B. On November 29, The Frontier announced it would drop the paywall. The words “now a nonprofit” were placed on the top of webpages alongside a “donate” button.

It wasn’t that things were going badly. The Frontier was more or less meeting its membership targets, and the staff was already turning out quality journalism, including stories about abuses within the county sheriff’s department that contributed to the sheriff’s resignation. But they were spending too much time on customer service and retaining their small pool of Tulsa readers, and Lorton could already see that growth would be difficult.

“It’s easy for me to pinpoint some successful websites out there, and most of them are nonprofit,” Lorton said in a December Frontier podcast, citing ProPublica and The Texas Tribune. “It’s hard to pinpoint the ones that are for-profit that are doing well.”

Lorton, 48, likens the switch to repairing an airplane while it’s up in the air. But in some ways, the timing couldn’t have been better. The 2016 presidential elections sparked a renewed interest in accountability journalism and a big pickup in donations to nonprofit news organizations. “From local public radio affiliates to established watchdog groups to start-ups that focus on a single issue, nonprofit, nonpartisan media is having a moment,” The New York Times reported on December 7.

That month, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation embarked on a “news match” program, offering to match individual donations to 57 nonprofit news sites—national, statewide, and local—up to $25,000 for each organization. Roughly $2.4 million was raised, including the funds from Knight. Jennifer Preston, a Knight vice president, says the program was an “opportunity to help nonprofits build a small donor base,” and that “several of the participants reported significant jumps in their annual giving campaigns.”

Robert Lorton says changing from for-profit to nonprofit was like repairing an airplane while in mid-air. But in some ways, the timing couldn’t have been better. (Photo by Kenneth Ruggiano)

The Frontier, which had just converted to nonprofit, didn’t participate in the program. But after a few months it received preliminary approval for a three-year, $50,000 annual grant from a local foundation and “several more verbal yeses in the same dollar range” from others, according to Lorton. About $35,000 has come in through the website from readers giving small amounts in the $25 to $50 range and another $40,000 from individuals and companies solicited by Lorton.

The first wave of nonprofit news startups began around 2005 and accelerated as the newspaper industry contracted and jobless journalists looked for new ways to stay in the game. They included national news sites (ProPublica), statewide/statehouse-focused outlets (the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism, the Iowa Center for Public Affairs Journalism, NJ Spotlight, VTDigger in Vermont), and local sites (Voice of San Diego, the New Haven Independent, Charlottesville Tomorrow, Tucson Sentinel, Voice of OC, The Lens in New Orleans).

The Institute for Nonprofit News, founded in 2009 to promote collaboration among the sites, has over 120 members, about 30 of which are local (not including statewide sites). INN executive director Sue Cross estimates that there are more than 200 nonprofit news sites across the country, and that the failure rate is under 18 percent.

But for local sites, survival isn’t assured, and growth has been tough for even the more established players. “It’s a smaller pond to fish in for support,” says Cross. “Local is going to be harder to sustain.”

The Frontier launched in April 2015, with an illustrious pedigree. Not only did Lorton have established roots in the newspaper business, but he hired two Tulsa World reporters—Ziva Branstetter and Cary Aspinwall—who were named Pulitzer Prize finalists on the same day it was announced they would join The Frontier. Branstetter, who was editor in chief, left The Frontier in April to join the Center for Investigative Reporting, a national nonprofit. Aspinwall left to join the Dallas Morning News in August 2016. Three out of four of The Frontier’s news staffers have worked for the Tulsa World.

The Frontier launched without an office or website, and its earliest stories were put on Scribd, an open-publishing platform. The staff now works at 36 Degrees North, a start-up incubator in downtown Tulsa filled with “hipsters and vegan coffee and West Elm furniture,” as Branstetter put it in an interview with CJR last year.

The building, which dates to 1917, is a former Ford dealership where Model-Ts were once sold. In the center sits the skeleton of a massive elevator, once used to move cars, now converted into work booths. The open-air feel, the high warehouse windows, and the bustle of activity from young entrepreneurs evokes the Golden Age of American manufacturing.

The Frontier’s five-person staff is squeezed along two tables in a tiny office, though they can reserve conference rooms, sound booths, and ad hoc studio spaces. The staff has taken advantage of the tech expertise of the entrepreneurs headquartered at 36 Degrees North; one fledgling video-production firm volunteered its services for The Frontier’s Election Night special on Facebook Live, asking only for credit and a token payment for the use of equipment.

It’s a smaller pond to fish in for support. Local is going to be harder to sustain.”

Lorton drops by a few times per week. On a recent visit, he conducted a meeting while sinking into a beanbag chair, an unusual experience for an executive weaned in the boardroom of a legacy media operation. “It was very awkward,” he laughs.

Criminal-justice stories have been the site’s specialty, and The Frontier has collaborated with The Marshall Project, the New York-based nonprofit site dedicated to covering that topic. Branstetter, before her departure, said she wanted to branch out and seek dedicated funding for a healthcare reporter. The Frontier, which also partners with KOTV, the local CBS affiliate, doesn’t usually aim to compete with the World or other legacy media. “There’s so many stories we pass up because we don’t have the manpower,” Branstetter said, “but the ones we do we really have to own.”

Did dropping the paywall and switching to nonprofit status change the nature of her job?

Branstetter said she was “actually less anxious . . . I felt that price point was too high, and I told Bobby [Lorton] that from the beginning. I was more worried about quantity when it was for-profit.”

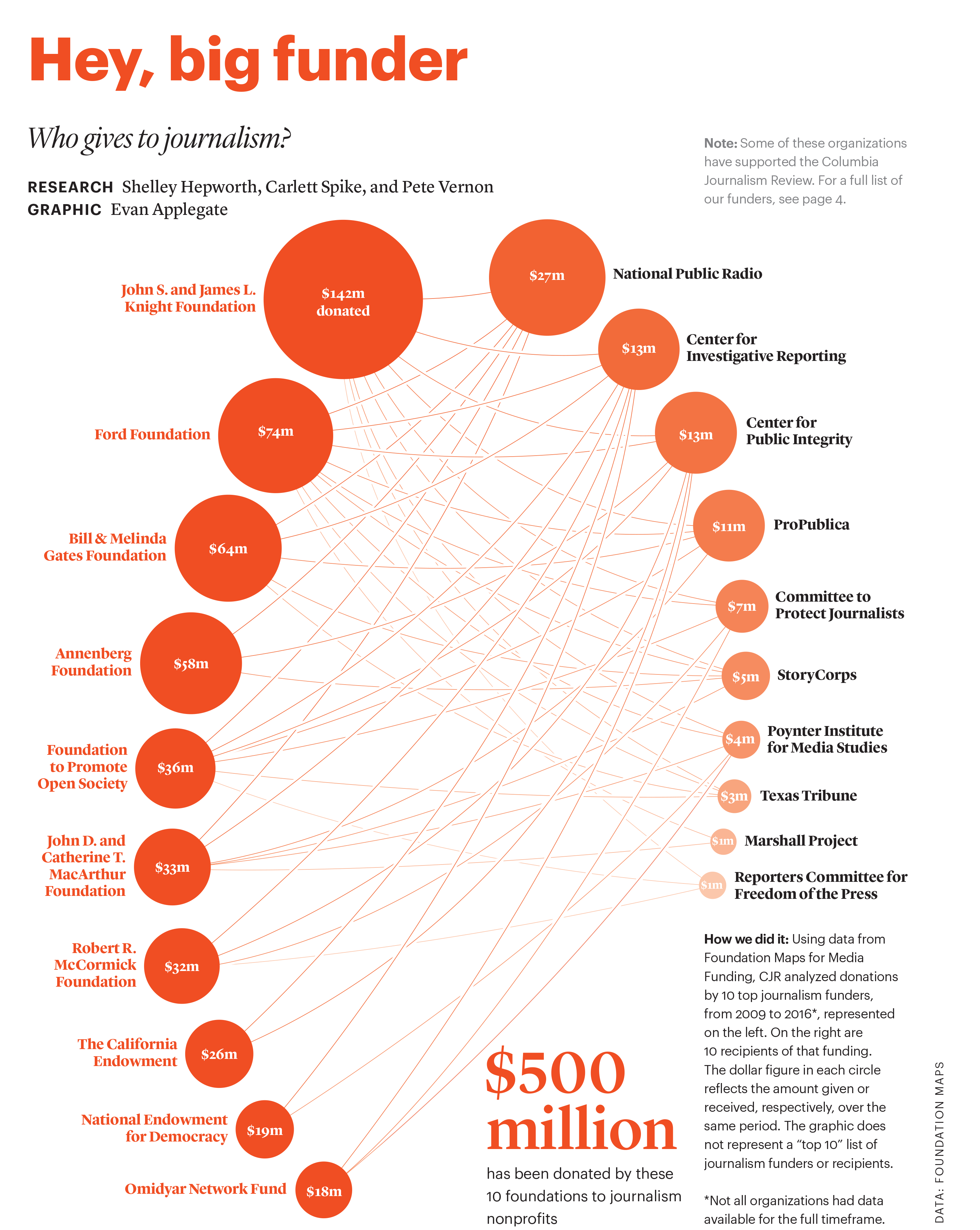

Which foundations donate to journalism nonprofits? Click chart to view larger.*

Traffic has doubled since the paywall went down, she said, and more readers are sharing Frontier stories on social media. The site also is more accessible to a broader audience that couldn’t afford to subscribe before. “We write a lot about disadvantaged people,” Branstetter said, “and I wanted them to be able to read the stories.” In her new position with the Center for Investigative Reporting, she said, “I want to continue working with local news organizations, including The Frontier.”

Two other local-news sites have recently made the switch to nonprofit—the San Antonio-based Rivard Report in late 2015, and the Honolulu Civil Beat last summer. The Rivard Report started as a two-person blog in 2012. Since it became a nonprofit, its staff has grown from four to 12, and founder Robert Rivard says that he will soon hire three additional reporters. “While we teetered on the precipice of profitability, ad revenue alone would not fuel our growth or long-term stability,” wrote Rivard on the site. “Venture capitalists who looked at the Rivard Report admired the people and the product, but not so much the balance sheet.”

Now, Rivard says “membership is growing, foundation and philanthropic support is growing, advertising and event revenue is growing, and our audience is growing.”

The Civil Beat, founded in 2010 by philanthropist Pierre Omidyar, has won numerous awards for reporting on criminal justice, minority communities, and the environment. But its subscription model never allowed it to break even, Editorial Director Patti Epler says. “People were reluctant to buy a subscription. Our readers tend to get their news from a lot of sources. ‘So why should I pay for news?’” says Epler. “When we switched to nonprofit, they seemed to adopt this notion that grassroots donations to nonprofit news send a signal that ‘this is the kind of news we want.’ ” The Civil Beat has 18 editorial and business staffers. Epler plans to hire more reporters to expand the site’s environment, heath, business, and government coverage.

Epler says that most former subscribers have become donors. Local foundations including the Hawaii Community Foundation and the Alexander & Baldwin, Inc. Kokua Fund help support the site.

The Rivard Report and Civil Beat both aim to attract money from national foundations. Relying solely on local money increases the risk that the nonprofits will offend donors when stories hit too close to home. “Almost inevitably your reporting is going to touch on something that affects a donor,” says Cross of INN.

“Eventually you’re going to piss off the people in town who control the purse strings,” says Steve Beatty, editor of The Lens, the nonprofit in New Orleans that specializes in politics and land-use stories. “Apparently we’ve been pretty good at that.”

One story may have cost The Lens its workspace, he says. Beginning in 2012, the site had enjoyed free office space in a building that houses Loyola University’s School of Mass Communication. Then in late 2014, The Lens published a report critical of the university president’s role on the city’s civil-service commission. A Loyola professor resigned from the publication’s board of directors as the story was being prepared, citing a conflict of interest. The school declined to renew its arrangement with The Lens, which left campus two weeks after the story was published. Laura Kurzu, Loyola’s vice president of marketing and communications, said in a statement that the decision not to renew was made “to make room for student programs and new resources.”

“That ended up costing us a good deal,” Beatty says, “because we’re now in a place where we pay rent and utilities, and I clean toilets and mop the floors.” That was not the first financial setback for The Lens. After the New Orleans Times-Picayune scaled back in 2012 to three editions a week and cut staff, “people started sending money our way,” says Beatty, and the staff grew to 13 members. But a year later he had to make cuts after losing some key donors. The site has “been on an even keel since then,” Beatty says, and has eight staffers—six on the editorial side.

We liberally steal ideas from each other. I don’t think you see that in the for-profit world.”

Voice of San Diego Editor in Chief Scott Lewis says that even when donors aren’t mentioned in sensitive stories, they sometimes have strong opinions and no scruples about voicing how they feel. “Often the most awkward situations come up if someone who’s a supporter thinks a story is inaccurate,” Lewis says. “You don’t want to change it because they’re a supporter, but you don’t want to oppose them just because they’re a supporter. There have been conversations when I thought they might have a point, and others when I thought they didn’t, and you just have to deal with it.”

INN requires its members to establish strong editorial-independence policies and disclose their major funders. “I think nonprofits need to continue to be vigilant that donors understand they don’t have a voice in coverage, and that foundations are not paying for coverage that supports their point of view,” Cross says. She counsels nonprofits to create as wide a donor base as possible—drawing from individuals, corporations, and local, state, and national foundations—so they are not overly dependent on a few funders.

That requires nonprofits to have people on staff with expertise in cold-calling, membership services, event planning, and grant writing—foreign to most journalists. Many of the early nonprofits that failed jumped right into producing stories without a fundraising plan or dedicated business staff, says Cross.

The Frontier works out of a startup incubator in downtown Tulsa. It collaborated with other entrepreneurs using the space for an election night special on Facebook Live. (Photo by Kenneth Ruggiano)

Founders of nonprofit-news ventures, says Beatty of The Lens, “should quickly come to terms with the fact that they are no longer journalists, they are small-business entrepreneurs.” The first hires, he advises, “should be a development director or fundraiser.”

Voice of San Diego’s Lewis, who has been with the site since its inception in 2005, says it was fortunate that Buzz Woolley was one of its founders. Woolley was a venture capitalist who had “a lot of experience with entrepreneurial nonprofits,” says Lewis. Voice of San Diego, one of the first digital news nonprofits in the US, has a handful of staffers on the business side of the operation. Publisher and chief operating officer Mary Walter-Brown in December launched the News Revenue Hub, a collaborative project in which the San Diego site is sharing its membership strategy and technology with five other nonprofits.

The idea behind the News Revenue Hub, according to its website, is to “help organizations with member recruitment and retention, audience engagement, and custom software installation” so that the participants, which include The Lens and the Civil Beat, “can focus on what they do best: producing high quality journalism.” Though it’s a one-year pilot project, funded by a Democracy Fund grant, Lewis says other news organizations have expressed interest in signing on, and the collaboration may continue. (Disclosure: CJR also receives funding from the Democracy Fund.)

“A lot of us do lean on each other through INN and conferences that we go to,” says Beatty. “And we liberally steal ideas from each other. I don’t think you see that in the for-profit world.”

Illustration by Mike Reddy

Beatty is happy to collaborate with public media and for-profit organizations as well. The Lens has shared content with public radio station WWNO, The New Orleans Advocate, and The Louisiana Weekly, an African-American newspaper. “We’re fairly promiscuous,” he says. Cross says that “about half our members reach their audience primarily by third-party sites.” Such arrangements allow them to demonstrate to donors that their reach extends well beyond their own websites, which themselves may draw relatively light traffic.

Despite the post-election Trump funding bump, nonprofit local news remains an uncertain proposition. Cross points to some under-the-radar success stories such as Philadelphia Public School Notebook, which covers education, Austin Monitor, which covers public policy, and The Chicago Reporter, which has covered race and poverty as a nonprofit news organization since 1972. But few local sites have been able to achieve the robust growth of nationally recognized outlets like The Texas Tribune and ProPublica. Many “have kind of plateaued, trying to figure out how to expand,” Cross says. Even established sites have suffered reversals over the years and most still employ fewer than 10 editors and reporters.

Eventually you’re going to piss off the people in town who control the purse strings. Apparently we’ve been pretty good at that.”

The Street.com reported on March 3 that Voice of San Diego has enjoyed a considerable fundraising boost since the election, but Lewis a few days later said that the bump only helped take the sting out of what had been a down year for giving by major donors. As part of a Knight-funded project launched in 2014 to help the Voice of San Diego and the Twin Cities-based MinnPost develop systems for managing and boosting membership, Voice of San Diego had set a goal to triple membership by the end of 2016; the site fell well short of that target, Lewis says. He does not consider the project a failure, however, as it helped fix what he called a “janky” membership program and pave the way for the News Revenue Hub.

While the Knight News Match yielded the $25,000 maximum for Voice of San Diego, Lewis is not optimistic that the site will be able to add to its 13-member staff in the short term. “It’s going to be a continual slog to keep adding one or two here or there,” he says. “It’s never going to have the kind of leaps that I may dream of.” Given the year-to-year funding cycle, he adds, “You’ve got to demonstrate your value again and again.”

That forecast doesn’t bode well for journalists who had hoped nonprofits could fill the gap as the collapse of ad-supported media takes its toll on local newspapers. And the picture is even bleaker for poor communities where residents have few resources to support quality journalism, however desperately it’s needed.

“A lot of journalists have been taught to let the stories speak for themselves,” Beatty says. But in the nonprofit world, that’s a luxury they can’t afford, he says: “You have to shout from the rooftops what a good job you’re doing.”

*This graphic has been updated to clarify that it is not a top 10 list, but simply a list of 10 major journalism funders and recipients.

Deron Lee is CJR’s correspondent for Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska. A writer and copy editor who has spent nine years with the National Journal Group, he has also contributed to The Hotline and the Lawrence Journal-World. He lives in the Kansas City area. Follow him on Twitter at @deron_lee.