In a New York Supreme Court last November, the conservative website Project Veritas launched its defamation suit against the New York Times in much the same way that Veritas’s founder, James O’Keefe, launches his viral videos—with a fusillade of accusations. Among the many allegations listed in the suit: an attempt to show that Times reporter Maggie Astor was biased against conservatives because she “was once interviewed by The New York Sun while wearing a shirt that said, ‘I hated Bush before it was cool.’ ”

That isn’t wrong, although Veritas’s lawyers leave out the fact that this happened more than thirteen years ago, when Astor was a first-year student at Barnard College.

The Times is being sued because of how it characterized two Veritas videos, which ran last September and alleged voter fraud in Minneapolis. Astor’s story, as quoted in the suit, called a Veritas video “deceptive” and said O’Keefe and his colleagues have “a long history of releasing manipulated or selectively edited footage.” Astor noted that Veritas released its first video just hours after a big Times scoop about Donald Trump’s tax returns, and she quoted an academic research group saying that a series of Veritas-promoting tweets by Trump and others resembled “a coordinated disinformation campaign.”

To many journalists, those statements would seem uncontroversial, the litigation a nuisance. But Veritas recently scored an important win when a New York justice rebuffed the Times’ efforts to get the suit dismissed. That means the Times, which has appealed the ruling, may now face a protracted court battle. And each side could soon be imposing onerous discovery and depositions on the other’s reporters and editors.

Veritas filed its suit in the New York Supreme Court, a trial court whose justices hear cases on a county level—in this case, Westchester County, a New York City suburb where Veritas’s office is located. And there’s evidence that the suit was a hot potato: two Supreme Court justices—including Alexandra Murphy, the daughter of New York State’s chief judge—quickly recused themselves without providing a rationale.

The decision in the Veritas case got little notice in mainstream or progressive media—even the Times didn’t mention it—but it was enthusiastically covered in conservative outlets such as The Federalist and the Washington Examiner. A Twitter-banned Trump took to video so he could congratulate Veritas on its win: “Whatever you can do for their legal-defense fund, we’re with them all the way. They do incredible work.” (The Times isn’t Veritas’s only target these days. Last month, O’Keefe filed a defamation suit against Twitter after it kicked him off the platform, while Veritas filed another defamation suit against CNN.)

The Times, in its response to the lawsuit, argued that Astor and another defendant, reporter Tiffany Hsu, were either telling readers the truth or were putting “unverifiable expressions of opinion” into their news stories.

That last bit is a handy term among media lawyers, the idea being that since most opinions can’t be proved true or false, they can’t serve as the basis of a defamation suit. As Times spokeswoman Danielle Rhoades Ha told me, “the term ‘opinion’ has a special meaning in defamation law, one that differs from the common understanding of the term,” adding that it refers to “descriptive statements [that] help readers understand the significance of the news.” In that sense, you could say that the Times is portraying “opinion” as something closer to analysis or color—like when a sportswriter says a ballgame was played on a “beautiful” day rather than reporting it was 74 degrees, or describes the shortstop as “clumsy” instead of noting he made three errors.

If that was the distinction, it was lost on the justice in the case, Charles D. Wood, who was elected to a fourteen-year term as a Republican in 2009. Wood noted Veritas’s argument that “a reasonable reader would expect a news reporter’s statements to be assertions of fact and not opinion.” He added, “If a writer interjects an opinion in a news article (and will seek to claim legal protections as opinion) it stands to reason that the writer should have an obligation to alert the reader.”

By framing his decision that way, Wood highlighted the key irony of the case: a court is pointing to Project Veritas as a possible victim of unethical journalistic conduct. Meanwhile, the New York Times must counter the blowback that comes from arguing that its reporters put “opinion,” however it’s defined, into its news stories.

THE VERITAS PIECE at the heart of the Times case opens with a Snapchat video featuring a man named Liban Mohamed—also known as Liban Osman—speaking in Somali and English, to no one in particular, about absentee ballots he had collected on behalf of his brother Jamal Osman, a local municipal candidate. His car is littered with envelopes, and he is seen saying, “Just today we got three hundred for Jamal Osman.” It isn’t clear from the video what’s in the envelopes, or when this was shot, or who was behind whatever was going on.

The video then cuts to another Somali man in Minnesota, Omar Jamal, who serves as Veritas’s key on-the-record source. Some of Jamal’s quotes leave a lot to the imagination. Here is how one of Veritas’s subtitles reads—with its parentheses, not mine: “I think he (Liban Mohamed) was (working for) both Ilhan Omar and Jamal (Osman) but I think he was more with Ilhan Omar,” referring to the Democratic congresswoman from Minneapolis.

Mohamed at one point is seen saying: “A campaign is managed by money. You cannot campaign with two hundred dollars or one hundred dollars you got from your grandmother or grandfather…. You gotta have fundraisers.” Most politicians would fully agree.

There’s more in this vein: An unnamed “ballot harvester” with a pixelated face makes allegations about Ilhan Omar’s campaign; an unnamed and unseen “former political worker” talks about taking absentee ballots from voters; someone identified as “Jamal, member” of the state’s Democratic Party, says that several ballots were returned blank. In another Snapchat scene, Mohamed says to a woman (in Somali), “There are winners and losers, right?” and she responds, “Yes, they will win with the Japanese”—but there’s no indication who “the Japanese” are or what their relevance might be. Throughout, videos are cut and spliced together in ways that make it difficult to tell what has been independently verified.

The video nevertheless was a sensation on the right. Then-president Trump blasted out his endorsement (“This is totally illegal”), as did his son Don Jr. and a host of other conservative activists.

That video, and another one that Veritas released the next day, came under scrutiny by mainstream news outlets, some of which wrote that Veritas’s work was shoddy. A USA Today analysis stated in a fact-check column that “based on our research, the claim that Project Veritas discovered a voter fraud scheme connected to Rep. Ilhan Omar is FALSE,” adding that “there are many aspects that are impossible to corroborate.” Snopes, the fact-checking site, said Veritas was spreading an “unfounded claim about Rep. Ilhan Omar and voter fraud.” Meanwhile, the local Fox affiliate in Minneapolis interviewed Mohamed, the man with the envelopes in his car, and quoted him as saying he was offered $10,000 by Jamal to claim he was collecting ballots for Rep. Omar. Veritas denies that.

One of the most withering reviews came from the Election Integrity Partnership, a nonprofit group backed by Stanford University and the University of Washington that researches the spread of misinformation on the Web. They reported on September 29 that Veritas’s video “made several falsifiable claims that have either been debunked by subsequent reporting or are without any factual support.” They went on to show that O’Keefe had teased in advance that the first video was originally to be posted September 28, but Veritas published it a day earlier, shortly after the Times exposé on Trump’s taxes.

About an hour after the academics’ report came out, Astor’s story in the Times went live. This was her lede:

A deceptive video released on Sunday by the conservative activist James O’Keefe, which claimed through unidentified sources and with no verifiable evidence that Representative Ilhan Omar’s campaign had collected ballots illegally, was probably part of a coordinated disinformation effort, according to researchers at Stanford University and the University of Washington.

Astor’s story adds that “O’Keefe and Project Veritas have a long history of releasing manipulated or selectively edited footage purporting to show illegal conduct by Democrats and liberal groups.” The story points out characteristics of the video to show why some allegations are unsubstantiated, but it provides less evidence for why it’s “deceptive.” Astor didn’t seek comment from Veritas, nor did she provide a link to the video. The Times story also didn’t mention incidents from O’Keefe’s more distant past, such as his guilty plea for his role in a scheme to infiltrate a Democratic US senator’s office, or the $100,000 he paid to settle a suit filed by a California man who said he’d been illegally taped in an undercover Veritas video.

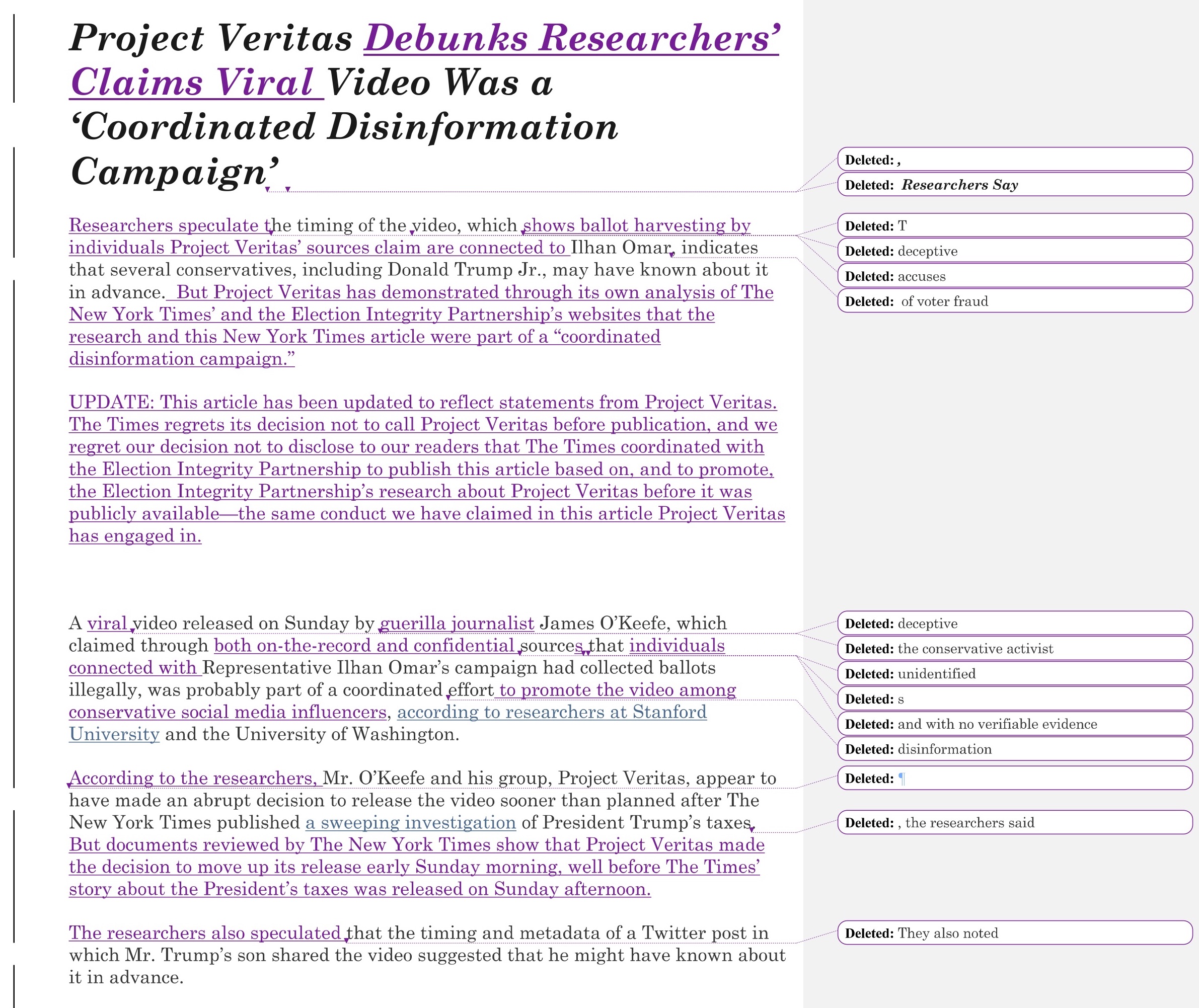

Elizabeth Locke, an attorney for Veritas, wrote the Times to seek a retraction and to state that the academics’ report was “fraught with factual errors and its own violations of basic journalistic standards.” She also provided a line-edited version of Astor’s story that included changes that would, in her words, “fully gut the original article,” starting with a revised headline: “Project Veritas Debunks Researchers’ Claims Viral Video Was a ‘Coordinated Disinformation Campaign.’ ” The Times did not take up Locke’s offer to publish her revisions.

Via court filing

The following week, Hsu cited the Veritas video in a story headlined “Conservative News Sites Fuel Voter Fraud Misinformation.” She wrote that the video “claimed without named sources or verifiable evidence that the campaign for Representative Ilhan Omar…was collecting ballots illegally.” Like Astor, she didn’t ask Veritas for comment, nor did her article link to the videos.

Several days later, Veritas filed its suit. It chose well in its counsel: Locke successfully represented a University of Virginia dean who was defamed by Rolling Stone in a bogus story about a campus rape. She has been part of the legal team representing former vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin, whose defamation case against the Times, filed nearly four years ago, will move to a full-blown federal trial later this year. And her firm is now representing Dominion Voting Systems in its litigation against Rudy Giuliani and others who peddled false conspiracy theories about the 2020 election.

The Times’ strategy of saying its reporters put “opinion” into news stories isn’t crazy. Its lawyers successfully used that argument in December in persuading a federal judge to dismiss a defamation suit filed by an anti-immigration activist, who had been characterized by the Times as a “white supremacist.”

Locke, in an interview, told me that the Times erred in using this strategy in the Veritas case. “Maggie and Tiffany are news reporters,” she said. “These pieces we sued on are in the news pages, not the editorial page. That context matters.”

AS I BEGAN WORKING on this story, in April, I emailed Locke to request an interview. I didn’t hear back from her right away, but a few hours later I did hear from my colleagues at Columbia Journalism School, where I’m a professor. A Project Veritas crew had made its way into the school, without advance notice and despite covid-related restrictions on visitors. They were walking the halls, looking for me. As it happens, I wasn’t in the office that day, but a lot of students were, and a few of them interviewed O’Keefe outside, after campus security came to clear the Veritas team out.

O’Keefe emailed me that afternoon: “William, I’m at Columbia University for the next 1-2 hours today if you wanted to meet up briefly for an interview…. James.” I told him I’d speak with him later.

We did talk a few weeks after that, in a conference call that included Jered Ede, Veritas’s chief legal officer. I asked some detailed questions about the videos.

For instance, when Liban Mohamed, the man with the ballot envelopes, was interviewed by Veritas, was he aware whom he was speaking with? “I wouldn’t know what Liban was or was not aware of,” replied Ede. “Certainly we don’t tell our subjects that we are recording them.”

What about the allegation raised by the Minneapolis Fox affiliate, that Veritas’s main source offered $10,000 to Mohamed to implicate Rep. Omar? “From my standpoint here, there is no truthfulness to that whatsoever,” said Ede.

What about concerns that many of Veritas’s key allegations come from anonymous sources? “Veritas’s journalism is well above and beyond the standard of most journalists,” said O’Keefe, adding that in the Times’ story on Trump’s taxes, “you couldn’t hear anyone’s voices in the interviews that were conducted.”

Why did Veritas post the first video a day earlier than originally planned, with the result that it ran the same day as the Times’ tax story? Ede says the Times piece was irrelevant: “We made a decision that the video would have a better viewership on a Sunday night than a Monday morning.”

The Times’ decision not to ask Veritas for comment was “a clear violation of basic journalistic standards,” Locke previously stated. So did Veritas reach out to people who are implicated in its videos? Ede said they did contact Ilhan Omar’s campaign, but that Liban Mohamed’s monologue in his Snapchat videos “effectively was his comment.” There’s no evidence in the videos that they reached out to several others linked by Veritas to election misconduct, or that they made those people aware of the allegations before the videos went live. And Veritas didn’t directly answer specific questions about this in a follow-up email.

The Times’ spokesperson won’t explain why its reporters didn’t contact Veritas before publishing. “Because the case is still in the early stages of litigation, we are not able to discuss the decision-making regarding this story,” said Rhoades Ha. As for not linking to Veritas’s videos, she said, “When we report on misinformation or disinformation, we often do not include a link to avoid further disseminating it.”

Astor didn’t comment for this article, and Hsu didn’t return several messages, but each provided sworn affidavits to the court. Astor didn’t shy from the conclusion she reached back in September, stating that Veritas’s work “appeared to me to employ many deceptive editing techniques, including grouping together short clips without context and using subtitles that inserted additional words into the statements of those in the Video.”

Justice Wood noted that “eventually, to prevail at trial, Veritas will have a high burden.” Proving defamation requires that its lawyers show the Times acted with “actual malice” or “reckless disregard” for the truth—that its reporters knew that what they wrote was false and published it anyway, or were reckless in not caring whether it was true or false. It can be difficult to find evidence—actual or circumstantial—to prove that case. Few plaintiffs make it that far.

Nonetheless, Veritas has managed to deploy a decision by a justice in the suburbs of New York City to portray itself as a warrior in the crusade against biased journalism. They say on their “Donate” page that they have raised more than $437,000 to cover legal costs in the case. Their strategy has been highlighted by conservative commentators ranging from Trump impeachment attorney Jonathan Turley to Fox News’s Brit Hume. They haven’t ruled out suing others who looked unkindly on their videos; Locke told me that they “focused on the Times first because it has the most breadth.” They might now force Times reporters and editors to answer difficult questions, under oath, while Justice Woods’s ruling is on appeal.

In the meantime, the lawsuit is serving as a useful talking point. Last week, the Times reported that conservative activists, including people at some point associated with Veritas, had mounted an undercover operation in 2018 to entrap FBI employees and H.R. McMaster, then Trump’s national security adviser. O’Keefe’s response, as quoted in the article: “Because The New York Times is losing to Project Veritas in a court of law, it is trying to smear Project Veritas in the court of public opinion.”

Bill Grueskin is on the faculty at Columbia Journalism School. He has previously worked as founding editor of a newspaper on the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation, city editor of the Miami Herald, deputy managing editor of the Wall Street Journal, and an executive editor at Bloomberg News. He is a graduate of Stanford University (Classics) and Johns Hopkins’s School of Advanced International Studies (US Foreign Policy and International Economics).