This article is a collaboration between CJR and the Committee to Protect Journalists.

It was the deadliest day for journalists in Afghanistan since the fall of the Taliban regime. On April 30, a double suicide blast in the capital, Kabul, killed nine journalists. Some died instantly; others clung, briefly, to life. Their names were Yar Mohammad Tokhi, Sabawoon Kakar, Abadullah Hananzai, Maharram Durrani, Ghazi Rasooli, Nowroz Ali Rajabi, Saleem Talash, Ali Saleemi, and Shah Marai, and they worked for a combination of local and international outlets—including AFP, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, TOLO News, TV1, and Mashal TV. Not long afterward, about 100 miles away, in Khost Province, BBC reporter Ahmad Shah was also killed—shot by a group of armed men while cycling. By day’s end, the journalist death toll was 10.

Afghanistan’s press corp is no stranger to murder: Journalists are killed far too often, and reporting on mass civilian casualties is a depressingly routine assignment. In Kabul, on the last day of April, those realities collided in a particularly shocking way. Reporters and photographers had flocked to cover a suicide bombing near the US embassy around 8 am, during the morning rush hour, when a second attacker, who’d flashed a press pass and a camera to get near the media gaggle, detonated his own explosives. It was a careful, coordinated attack, specifically targeting members of the press.

Working in collaboration with the Committee to Protect Journalists, CJR set out to learn more about the reporters who died. In interviews with 22 of their relatives, friends, and colleagues, we heard repeatedly that the fallen journalists would be among the first on the scene whenever an attack took place—a diligence that ended up costing them their lives. Many were their family’s sole breadwinner, supporting children, spouses, siblings, and parents, some of whom are pregnant or severely sick. Most were young. One, Maharram Durrani, was days away from starting production work on RFE/RL’s weekly women’s program, part of a small, yet vital, cadre of Afghan female journalists.

You can read their stories below, or by clicking on each of the journalists’ names or photos individually. All interviews have been edited for length and clarity; one, with Mashal TV’s Reza Adeli, has been translated.

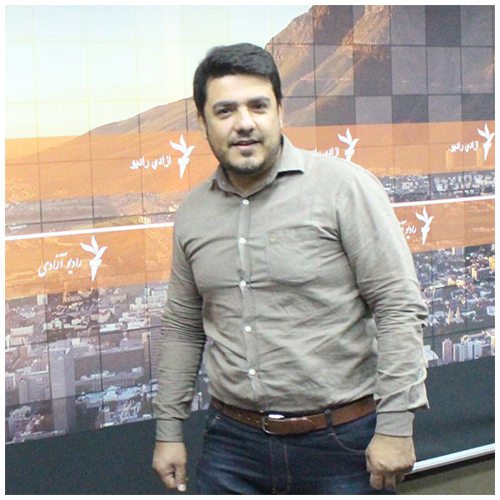

Yar Mohammad Tokhi

TOLO News, cameraman

Tokhi, 54, had worked as a cameraman for TOLO News and TOLO TV for 12 years. He was due to get married in a month, TOLO reported.

Photo courtesy TOLO News

Atta Mohammad Tokhi, Yar Mohammad’s brother: “I live in London now. Everything was going on normally and suddenly I received this news that my brother was gone, that he’d passed away. It wasn’t acceptable for me, I didn’t believe them—when I rang his phone number, one of his colleagues picked up the phone and he was crying and told me that he just died, that they killed him, and I said, ‘Are you are telling me the truth or are you lying to me?’ He said, ‘No no, I am telling you the truth, this is the truth.’”

Lotfullah Najafizada, director of TOLO News: “Tokhi was 54. I only found out he was 54 when I looked at his passport just a few days ago. He was a very sharp guy, he looked much younger to me.”

Waheed Massoud, BBC World Service production executive, friends with Tokhi: “He was somebody who was toughened by hardship in life, somebody who, from a very young age, had to take more responsibility than his peers his age would take. Because he had lost his father at a young age, him and his brothers had to look after the family, the siblings, and a mother who was often sick. He was a hard-working person, he had to work and educate himself and finish school. He was a very quiet person—very composed, very thoughtful—and a family person with lots of positive values.”

Atta Mohammad Tokhi: “He was supposed to get married on the 20th of this month. He’d printed his wedding party invitation cards. He bought furniture for his room: a bed, and rugs and a TV. I gave them all back to his fiancée, and she accepted them with teary eyes, and she said, ‘I’ll keep this stuff as a memorial for myself.’ She was really, really sad and she couldn’t stop crying. She was not feeling well—she was not able to walk, even—and my mom, at the same time, she was not able to stop crying. [She kept saying,] ‘He’s coming back,’ and ‘Where did he go?’ [The attack] happened at 8am, and at 8am he left the house. And they brought him back in a coffin.”

Rateb Noori, AFP video correspondent, worked with Tokhi at TOLO News: “In Afghanistan, when you’re over 20 years old, your family keeps pressuring you and forcing you to say yes to marriage, unless you have a very critical financial situation. So, Tokhi, he got engaged when he was 53, I think, last year, and he was about to get married. Even now, he wasn’t feeling OK financially, especially because his sister has cancer. Recently, I found out that he sold his bicycle to help her. A bicycle is not more than $80. That’s a crisis of financial status.”

Najafizada: “The day before he was killed, he was with his fiancée. They were looking at wedding halls, to book a venue for their wedding, and he had a ring on his hand. What made him a little bit closer to me recently was the story of his sister, who is fighting cancer. Tokhi came to me at least three or four times in the past two months seeking help, financial and otherwise, to treat his sister. We did what we could. I think he sent his sister to Pakistan and India for treatment, with not much success.

“For some reason, in the past month or so, he was the first person I would run into the office every morning when I’d arrive at work. When I’d arrive around 7, 7:30, he was sitting outside the office with his cup of tea in his hand, enjoying the sun for 10 or 15 minutes before we convened for our assignment meeting each morning. And I asked about his sister every day. I was thinking about it after we lost him. That was such a coincidence. It bothers me, you know. The other day when I arrived and I couldn’t see him. That was very, very hard. He’s probably the closest person I’ve lost at work in the last two to three years.”

Saad Mohseni, director of MOBY Group, which owns TOLO News: “[The newsroom] is very stoic; they don’t give up that easily. But there is always some sort of an impact. Someone you’ve been dealing with and seeing, who’s been there for 12 years, all of a sudden is no longer there. The impact is dramatic. To not be there because something has happened that relates to your work or is part of your work, obviously that impact is even more. It also shows how fragile we all are, and how this could happen to any one of us. We’ve experienced this sort of thing before, and it’s not easy.”

Muslim Shirzad, former presenter with TOLO News: “His experience made him more than a cameraman; he was, indeed, a journalist, a person who could do interviews. As we saw in the footage that came before the second explosion, he went to the scene and interviewed people about the first explosion. At TOLO News, it isn’t possible, in lots of cases, to just send a cameraman and [tell] him to do a report on an issue. Tokhi could do it, and he did. But sadly he lost his life, too.”

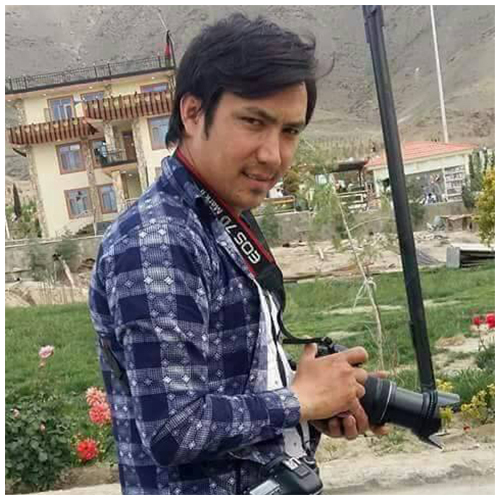

Sabawoon Kakar

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, reporter

Kakar, 30, worked as a video journalist for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Afghan service, Radio Azadi, for five years, and reported on counterterrorism operations, regional security, and social issues in Afghanistan. One of his last articles before his death was on a battle between Afghan security forces and Taliban militants.

Photo courtesy Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

Qadir Habib, senior editor with RFE/RL, based in Prague: “Kakar was a key member of Radio Azadi’s video team who was just a day short of completing his fifth year with RFE/RL. He worked on feature stories, social issues in Afghanistan, stories about counterterrorism operations. As I remember, he was always just running towards the bombs and the scene. He wanted to be ahead of any other journalist. I talked to him when he was coming back from the scene of some bomb blast or suicide attack, and sending us video, I told him, ‘Be careful, Sabawoon, don’t rush to the scene, your life is very important to us.’ But he told me, he was careful, but he wanted to be the first, he wanted to get the small details.”

Malali Bashir, reporter with RFE/RL, based in Prague: “He also produced a show that was focused on sports news. That was his area of interest. He worked with me on one of the reports we produced. We wanted to investigate corruption allegations within the cricket board of Afghanistan, and why Afghanistan still doesn’t have a national women’s cricket team. He was really interested in stories like this. Previously he worked with me on another report that, because of some editorial issues, we couldn’t publish. A woman was murdered in Kabul, but we couldn’t report this because the trial was going on, and we couldn’t [publish] it before the trial was held. He won’t be able to see the report come out.”

In March, Kakar worked on this report on women’s rights.

Aziz Ahmad Tassal, head of the Kabul Press Club, worked with Kakar in Helmand Province in the 2000s: “I remember, we had a live program on the radio, and someone called us, and me and Sabawoon were on the mic. They used a really bad word: The person said, ‘Why are you playing this song, don’t play the song on the radio.’ And he used a very bad word. Sabawoon was very upset. He said ‘Look, what we are doing….In Helmand, we want to bring happiness to the people. But some people blame us. Some listeners disturb us, some listeners attack us, and say don’t play songs.’ He said a song is one of the best things, people should be happy about it.”

Noorgul Shafaq, producer with BBC in Kabul, worked with Kakar at RFE/RL: “When we left the office, we were [usually driven home together]. He was a very social guy. He always made jokes and entertained people by saying very funny things. I remember when we sat in the early morning news meeting, everybody was waiting for what Sabawoon Kakar would say today, what kind of jokes he would make.”

Tassal: “I went to his house; someone gave me money and I gave that to his mother-in-law. I saw his little, small son. I took a picture of him. He was really sweet. I gave him an [envelope] with the money in it, for his family. He was so happy with it. Just three days ago, his wife had another baby.”

Our colleague Sabawoon Kakar who lost his life in Monday's suicide attack in Kabul while being on the line of duty, is not here to welcome his newborn son. Now he has two sons. #KabulAttack #Afghanistan pic.twitter.com/IKTp8o8AAL

— Malali Bashir (@MalaliBashir) May 5, 2018

Bashir: “They took him to the hospital, and then they asked for his blood type. My colleagues were able to bring the blood from the blood bank. Then they operated on him. Once he was operated, [they took] the shrapnel out from his body, and then he went to another surgery on the same day. And within a few hours we were told he is no more. And our office, our colleagues here in Prague and in Kabul, everyone was devastated.”

Habib: “He was working on a series of profiles of suicide attack victims. We talked to their relatives and family members about those people who lost their lives in these terrorist attacks. He was going and talking to these people, and he told me he felt really bad for them….He told me it wasn’t an easy thing to do, that it’s not an easy project. But he [also] told me it was a very important thing we were doing. Ordinary, normal people—civilians—are targeted in these attacks, and losing their lives. Unfortunately, Sabawoon himself became one of those victims.”

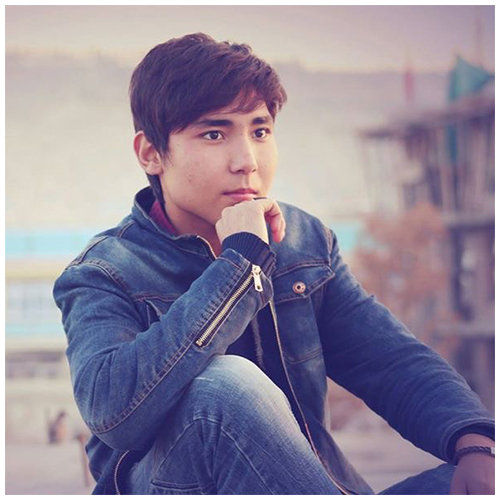

Abadullah Hananzai

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, reporter

Hananzai, 26, was a video journalist with RFE/RL’s Radio Azadi. His last public Facebook post, on April 25, was a tribute to his former colleague Abdul Manan Arghand, a journalist who had been shot dead by unknown gunmen the previous week.

Photo courtesy Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

Bashir, RFE/RL: “We were in shock here in Prague. Our office was in turmoil, everyone was running around. We wanted to not only confirm with the authorities but we wanted to see his face and confirm that he really was dead. So our colleagues from the Kabul bureau went to the area. They received his body and they confirmed that he was dead.”

Habib, RFE/RL: “He was working on this anti-narcotics project we have, which is called Caravan of Poison. I met him last summer when I was in Kabul to provide them with training for producing this anti-narcotics program. We were talking in the workshop about the challenges we might face while producing this program, because the illicit drug trade in Afghanistan is a very complicated business, with smugglers, drug lords….It’s organized crime, gangs are involved in this business. I was talking about these challenges and I remember very well that Hananzai smiled and told me, ‘It doesn’t matter how difficult and how problematic this project could be.’ He was not afraid of covering those stories. He told me that what matters is that we reveal the truth and provide people with the most accurate information. I was really amazed by that courage.”

Saber Aziz, news manager at Kabul News, worked with Hananzai: “He worked for three years in our office as a correspondent and journalist in the field [before he joined RFE/RL]. He went to [sites of] suicide bombings, he traveled to many provinces. He was a journalist but he was also working as a humanitarian worker. He helped people during his job. I have his video from one explosion, he was carrying an injured person from the area, carrying them out to a hospital. He was a very good guy.”

Bashir: “He was young, talented, he was able to make a good name for himself in a very short time. He was in his late 20s, he was married a year ago. So he was about to celebrate his wedding anniversary.”

Abadullah Hananzai on his wedding day last year. Photo courtesy Saber Aziz.

Noori, AFP, friends with Hananzai: “He was studying Persian Literature at Kabul University. I come from the same background, my [degree] is in Persian Literature. Sometimes we would talk about the subjects of the university, the problems he had with teachers, [issues] he faced….When I saw him he was very hopeful. He told me ‘Dude, I’m very happy, because now I have a stable job, I can focus on my work, I can focus on my future. I can have a brighter future, probably.’

“He graduated last year from the university, and he was supporting not just his family, but also his in-laws’ family. His father-in-law and mother-in-law were both very sick. He was basically not a son-in-law, he was also a son. I’m in touch with his sister-in-law and I talked to her after this incident. She was very upset, and she kept telling me he actually was just like a brother to her, and like a son to her parents.”

Maharram Durrani

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, incoming producer

Durrani, 28, was supposed to start her new job on Radio Azadi’s weekly women’s program on May 15 according to RFE/RL. The journalist had previously worked as a news anchor with several media outlets in Afghanistan and as a producer for the Afghan online music channel Radio Salam Watandar. She was also a third-year Islamic law student at Kabul University.

Photo courtesy Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

Bashir, RFE/RL: “She recently joined RFE/RL. She was going to training sessions, and she was on her way to the office, and then she came under attack. She was also in her 20s. She was very dedicated. She was interested in covering issues related to women’s rights. And she wanted to focus on this area because she believed it needs more attention in a country like Afghanistan. She wanted to focus more on the extremism that is giving a bad name, or a kind of different face, to the religion of Islam.”

Habib, RFE/RL: “Just before she joined us as a journalist, she took part as a guest in our call-in show about women’s role in the society, and journalists’ role in providing accurate information to other people. I remember a quote of hers, when she was talking in that debate, describing why she wanted to be a journalist and why it’s important for her as an Islamic law student to be a journalist. She said she wants to provide people with accurate information about Islam—[that] it’s not the religion that extremists talk about. She wanted to provide people with what she called the true meaning of Islam….She was a very intelligent, educated, and dedicated woman as a journalist. When I listened to that program she was part of, you could hear that.”

Lynne O’Donnell, former AFP and AP Kabul bureau chief (didn’t know Durrani): “We’re a little bit away yet from women being in significant numbers working in day-to-day journalism. I have friends who have done it, Afghan women, who have done it very successfully. But they’re exceptional people and they also have rhinoceros hides that enable them to overcome prejudices and the harassment that goes with being a woman in Afghanistan. She clearly had a lot of fortitude, and it’s a double tragedy that she’s gone.”

Bashir: “There are some topics only women can cover. For example, if we want to talk with families of anybody, from extremists to soldiers to police, sometimes people don’t want their women to talk with men, because Afghan society, you know, there are rules. So women journalists, particularly, play a very important role, by talking with the marginalized, with a part of the society that is not allowed to mingle with men, who are silenced in a way where nobody will talk with them, nobody will ask their views—not because people are not interested, but because they are not allowed to talk with men. There are things only women can cover and men cannot. So her role was very important.”

Ghazi Rasooli

1TV, reporter

Rasooli, 24, had worked for 1TV for four years and reported on criminal and terrorist incidents. The day before he was killed in the blast, Rasooli interviewed the Interior Ministry spokesperson about the security situation in Afghanistan.

Photo courtesy Hamid Haidari, 1TV

Najafizada, TOLO News: “I went to the emergency hospital, which is an Italian-NGO-run hospital. I looked at seven dead bodies there, and three of them were journalists. [One of them] was Rasooli, the Channel 1 journalist: A young guy, a new starter in the business, but a very shining star. He was becoming one of the most well-known journalists in the media industry.”

Abdullah Khenjani, editor in chief, 1TV: “He joined four years ago as an intern at our station. He was mainly involved with 2014 elections coverage at that time. Later on, he became one of our journalists in our newsroom at 1TV. So he was following not only security and political stories, but he was also engaged in social and economic [stories]. He covered more than 100 suicide attack incidents in Kabul, and he was also very familiar with the criminal cases that were happening in Kabul.”

Hamid Haidari, worked with Rasooli at 1TV: “He was studying at Kabul University. He was from northern Parwan Province, but most of his life was in Kabul. His father was also, in the past, a member of the Afghan government, and his uncle had also been a minister in the Afghan government. He was part of an Afghan political family. His father, his brothers, were educated people.”

Khenjani: “He was one of the kindest people I have ever seen in my life and that’s why, if you came into our newsroom today, you would find every colleague crying, as if they have lost one of the members of their family. He was younger than anyone else in our newsroom. The main thing that really hurt us was that he had a personality that wanted to take more of the responsibility than others at our station—he was ready for sacrifices all the time, and he lost his life. He was very kind, he was talented, he was passionate—he had a great personality and he was very good when it came to helping others.”

Zakarya Hassani, former 1TV reporter, worked with Rasooli: “A few days ago, last week, a group of friends, a group of colleagues from 1TV, were talking with each other. Ghazi was living in the Northern part of Kabul, in a really green district. He invited us, it was supposed to be [three days after the attack], to go to his place, to his garden. We planned to go and sit with each other, chat with each other, to talk about our past, our good memories we have together. Unfortunately this [didn’t] happen, because now we don’t have Ghazi. As one of our friends said, instead of us being his guests, unfortunately he is now the guest of Allah, the guest of God.”

Nowroz Ali Rajabi

1TV, cameraman

Rajabi, 31, a cameraman, had worked in the media for five years, including a year at 1TV.

Photo courtesy Hamid Haidari, 1TV

Mahdi Mudabber, news editor at Afghanistan-Ma newspaper, studied with Rajabi: “We were classmates in 2008 at Kabul University. He was studying in the cinema department of the fine arts faculty. He was a talented guy, and he was hard-working. He was humble, and he was ambitious. As I remember, when we met each other he was always smiling. He was a good friend of mine. He wanted to have a better future for his family and for his country.”

Khenjani, 1TV: “Personally, he was open, always smiling, not talking so much at all, not arguing at all, very kind. He [listened] to everybody without consideration of who they are—he was one of the best guys we ever [had here]. I think that was related to his family background—he came from a working-class family and he always wanted to do something, and this job was really meaningful for him.”

Hassani, formerly at 1TV (left before Rajabi joined): “His mother is dealing with an illness, his wife is pregnant. Nowroz Ali, very sadly, was the only breadwinner of his family. Now he’s not alive anymore, his family unfortunately doesn’t have a breadwinner. This is really sad.”

Haidari: “He was a kind man. He was so active. He was the first guy to go to the site to cover every incident. He was 31 years old. He was the only man in his family. He has no brother, no father. [I went to visit his mother in her home.] His mother was not able to stand, and she was crying, and her condition was bad, and she told me, ‘Where is my son?’ And I had nothing to say. I was sitting in front of her. She was crying….And I had nothing to say to her.”

Saleem Talash

Mashal TV, reporter

Talash, 24, worked as a reporter for Mashal TV for two years. Shortly before the second bomb exploded, Talash texted friends warning them against using the road close to the scene of the first blast, according to TOLO News.

Photo courtesy Mashal TV

Reza Adeli, director of Mashal TV: “It was about two years since Saleem Talash started working for us. I was the one who interviewed him for the job. It was his first time applying for a job. Talash had studied journalism but he didn’t have any work experience. He was very interested in the job but I wasn’t willing to hire him because of his lack of experience. One of the things he told me during the interview was that if you or other offices don’t hire me, where else would I get work experience? We talked some more and eventually I decided to hire him. Since then, he had worked with us for two years.

“He was a very hard-working person. I was always joking with him telling him that the last name, Talash [meaning a person who puts his best effort forward], that he had chosen for himself, really is befitting. And it was true, he was that kind of a person. He would tell me, ‘The last name that I have chosen is not random. I really do love to put my best in all the work that I do.’ He was an amazing guy and he had a lot of hopes. He hoped to one day work with the international media.”

Najafizada, TOLO News: “He was another journalist with great potential. What happens, with some of these newcomers into the industry, is my colleagues remind me that these are important journalists who might potentially work for us in the future. His name was certainly raised.”

Adeli: “Two months ago he got engaged. He had plans to get married after the month of Ramadan. He was facing economic hardship. A week before that incident killed him, he came to me, and asked if it was possible to get three months of his salary in advance so he could pay for his wedding expenses. I told him we would work something out.”

Ali Saleemi

Mashal TV, cameraman

Saleemi, 19, began working as a broadcast reporter and camera operator for Mashal TV a week prior to his death, TOLO News reported.

Photo courtesy Mashal TV

Adeli, Mashal TV: “Ali was a hard-working boy who lived with his grandparents. He had lost his mother a while back, and his father is [away] for work. He was 19 years old and had recently graduated from high school and wanted to go to college soon. He was working as a cameraman for us.

“The day the suicide bombing happened, because he was young, we wanted to send someone else instead of him. One of our colleagues, who is in charge of other videographers, was supposed to go the site of the suicide bombing. I told Ali not to go but it was early morning and no one else had come to the office yet….Ali Saleemi had his mind set, and insisted that he should be the one to go. Half an hour later, we heard about the explosion and ran to the site, and found out that he and others had been taken to the hospital.”

Shah Marai

AFP, photographer

Marai, 41, joined AFP’s Kabul bureau in 1996 as a driver and translator. He began taking photos on the side, for a time simply signing them as “stringer,” so as to not draw unwanted attention. For some of 2000, Marai was AFP’s only person in Kabul and called in information via satellite phone to the Islamabad bureau. In 2002, he became a full-time photo stringer before eventually becoming the agency’s chief photographer in Kabul.

Photo courtesy AFP

Sharif Hassan, Washington Post correspondent in Kabul: “Usually I rush to the scene of these deadly attacks for the Post, and I saw him all the time. He was calm, friendly, and very, very focused on his work. He was earlier than anyone else, often, at the scene, and his photos, if you go through them, you can see they are of smoke, and fire, and blood, and corpses. I went through all the photos, and I remembered that this guy was earlier than any one of us at the scene, and he was focused so much on his work. The day he was killed, in the latest blast in Kabul, [someone] interviewed the district police chief of the area. And the district police chief told him that he had a brief encounter with Shah Marai, and he told Shah Marai, ‘Your life is much more important than taking photos, go away,’ but he said, ‘No, taking photos is more important than my life.’”

Noori, AFP, worked with Marai: “Generally, when it came to attacks coverage, other media would come, and the first thing he’d do would be to call the competition, Reuters and AP photographers, and talk to them, and tell them about the explosion, about the place he was going to. Probably he was competitive, but always, I remember, he would call the photographers from Reuters and AP and ask them if they wanted to go together to cover the scene or not.”

Marai took this photo in December 2015. It shows an Afghan policeman keeping watch near a pile of burning drugs on the outskirts of Kabul. Photo courtesy AFP.

Habib Zahori, former New York Times correspondent in Kabul, now living in Canada: “He was from the district of Kabul called Guldara. He grew up in Kabul. He married twice. He had six kids. His family had this genetic problem, children would be born with blindness. I think three of his brothers were blind, and two of his kids. His youngest child was the only daughter. She was only two weeks old when he died.”

Noori: “I know that he used to bring his little sons to the office sometimes, whenever we had a party, or gathering, or any other small event. He’d love to bring his sons. And there were often days when his wife would call him and his little son would be on the phone, asking him to bring him chocolate.”

Massoud, BBC, former AFP correspondent in Kabul: “He started as a driver for AFP. But then every day, working with photographers, he was very enthusiastic; he tried to help them. In the good old days—when digital cameras didn’t exist, and people were taking photos through negatives—he would volunteer to wash films. So he learned it by doing it. And then he was given the opportunity to take photos every now and then, and he showed a sharp eye for photography and he took some good photos. And then after the end of the Civil War, when the Taliban regime took over Afghanistan, there was no foreign correspondent in Afghanistan, photography was banned, but he was still working with AFP and he would take—at great risk—he would take photos in secret, in hiding. He told me how he would take a small camera, hide it underneath his shawl, and go and take photos in the Kabul stadium or elsewhere, and try several times, because he couldn’t look through the lens to make sure the photo was focused. It was just putting it down there and taking photos. Out of every 10, 20 photos, one photo would be good enough to be transmitted back to AFP headquarters. So that was his journey, the way he became a proper photographer, and later on he was given training.”

Marai took this photo in January 2016. It shows relatives reacting during the funeral of Saeed Jawad Hossini, 29, who was killed in a suicide attack on a minibus carrying TOLO News employees—seven of whom were killed. Photo courtesy AFP.

O’Donnell, former AFP and AP bureau chief: “He understood light in a very unique way. In the AFP bureau, I worked with him and with Massoud Hossaini. They were the staff photographers, and they had, in their corner of an L-shaped office, their favorite photographs blown up to painting size and hung on the wall. There were a couple that Shah Marai had chosen to blow up and hang that used light in a very similar way. One of them was of name tags on the toes of a cadaver. It said so much. There was no gore in it. It was the feet of a body standing out from a darkened background with a tag on one of the toes. If you see a photo like that your first reaction is to recognize that it’s a dead body and that it has been processed, and then the question comes into your mind, how was the photographer able to get this photo? And photographers are usually only able to get photos like that if you’re in a situation of crisis, or some other abnormal time. And so even though it was a gentle image, the undercurrent of it was representative of the violence that Afghans live with.”

Andrew Quilty, freelance photographer in Kabul: “I’d offered all the wire services here to photograph Marai’s funeral, because he had so many friends, and I thought it was the last thing any of them would have wanted to be doing, covering his funeral. I ended up mostly doing it for AFP. I kind of felt like I was taking his role, in a sense. It would have been something he would have covered if it had not been him that was being buried.”

Photos of Shah Marai’s funeral, courtesy Andrew Quilty.

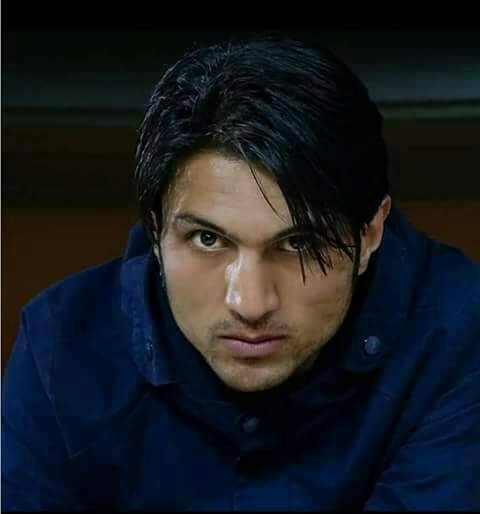

Ahmad Shah

BBC, reporter

Shah, 29, was killed on the same day as the Kabul nine in a separate incident in Khost Province, where he worked as a multimedia journalist for the BBC. He was shot by a group of armed men.

Photo courtesy BBC

Dawood Azami, BBC multimedia editor, based in London: “His father worked as a school teacher in the past in his native Khost Province, and then he left teaching because it didn’t bring him enough money, so he opened a grocery shop in Khost City. So his father has been a shopkeeper, and Ahmad Shah was his eldest son. He was 29. He had four sisters and one brother, who is a teenager. They had a lot of hopes for him, a lot of dreams for him.

“His father said he tried his best to persuade him not to choose journalism as a career. He said that he asked him to do something else. He said that his son insisted that, no, he liked this profession, he wanted to be a journalist, so his father told him, OK, if you want to become a journalist, if you want to remain as a journalist then you must be neutral, because journalists must be neutral. This was the advice even his father had given him, and this was his motive. As far as possible he was neutral, he tried his best to be neutral.”

Aria Ahmadzai, BBC, also worked with Shah at Radio Killid: “Before the BBC, me and Ahmad Shah were working with local radio. He worked from Khost and I was working from Kabul. At that time, I was a news announcer, and every night we had Ahmad Shah’s report from Khost. I didn’t meet him during those seven years, I just called him and asked him, ‘What can you do for a news bulletin, do you have a news report today?’ And all the time, he’d say, ‘Yeah, I have a report.’”

Azami: “He started working with us as a freelance reporter from his native Khost Province. But more than a year ago we decided to appoint a permanent reporter in Khost, because it is an important province of Afghanistan, and that person would also cover the neighboring provinces of Paktia and Paktika. We thought he was the best candidate. He was known to us, and we checked his language skills, his reporting skills, his sense of news, and information about his part of Afghanistan.

Shafaq, BBC: “He was a very talented guy. He helped his people to raise their voice about problems and issues they had with the government, and also with the Taliban and others. He worked on many stories. He had reports on decreasing mother and baby deaths in Khost….There was a story about tree-planting in Khost. And also on the border with Pakistan, there was fighting between Pakistani militants and Khost locals. He covered that story.”

Ahmadzai: “He was 29. He got engaged seven months ago, but he didn’t see his fiancée, because of the culture of Khost. [At one point, one of] my colleagues, she was kidding with him, she said to him—she knew that he was engaged—she said, ‘We are all in the office, why didn’t you select [one of] us as a life partner?’ She was just kidding with him. He didn’t say anything, his face became red. He didn’t know what to say. Because in Khost, girls and boys are separated and they never talk. The culture is like that, it’s not like Kabul, where you can sit with boys, with your friends, you can talk, you can go for coffee. In that culture it’s completely different.”

Zahori, former New York Times correspondent: “I only read one piece by him. He was talking about this one village that was completely abandoned. It was a brilliant report. It was beautiful. There was so much emotion attached to it. I didn’t know at the time who had written that piece. Later on, when they reported this journalist was killed and they started circulating that piece again, that’s when I realized he had written it.”

Azami: “I found his father to be very strong, because he said, ‘This is how Afghanistan is, this was his fate.’ On the same day he was killed, nine other journalists were killed in Kabul in a suicide attack. His father said that he and Ahmad Shah spoke about that incident, and he asked Ahmad Shah whether any of his BBC colleagues had been injured or killed in the Kabul blast. He said Ahmad Shah told him that his colleagues in the BBC Kabul office were safe, luckily, but that he knew some of the journalists who were killed in Kabul. Only 20 minutes later, after they had that discussion, he was killed. He didn’t know he would be killed so soon. He was worried about his BBC colleagues.”

Jon Allsop, Aliya Iftikhar, and Mehdi Rahmati are the authors of this article. Jon Allsop is a CJR Delacorte Fellow. Aliya Iftikhar is Asia research associate at the Committee to Protect Journalists. Mehdi Rahmati is social media associate at the Committee to Protect Journalists.