Journalism as a profession is more art than science. There are few codified rules of the trade, no official list of industry do’s and don’ts. All of which makes the unofficial pipeline of advice—words of wisdom from one journalist to another—more important than ever.

CJR reached out to an array of prominent journalists, from veterans and legends to recent grads and up-and-comers, and asked them to share the best advice they’ve received, words that have stuck with them as they’ve built their careers.

The following responses have been edited for length and clarity.

TRENDING: Photographer behind graphic Charlottesville image recounts near-death experience

Wesley Lowery is a national reporter at The Washington Post.

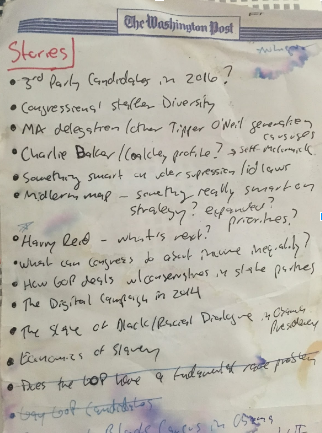

“One of the first editors I worked for after joining The Washington Post in 2014 was Terence Samuel, who at the time ran the paper’s congressional coverage (now he’s deputy managing editor at NPR). He told me that he wanted me, at all times, to be thinking of story ideas and writing them down. After every interview, what were two new leads? After every staff meeting, what tidbits were mentioned that would work as a stand-alone piece? When reading coverage by colleagues and competitors, what fact, statistic, or concept—often mentioned in the middle or end of the story—cries out for its own story, or series? What themes are surfacing in coverage by smaller, or more locally or regionally focused outlets that would benefit from coverage from a larger outlet with more time and resources?

Making these lists became an obsession of mine. The key, for me, was being unafraid to write things down, and stimulate that side of my brain. I still keep the first list (below), that I wrote at [Samuel’s] urging, on my nightstand. As you can see from the picture, it was just a list of disjointed thoughts and overly broad concepts. My lists now strive for razor precision. But I did end up writing a thing or two from the bottom of that first list, and dozens more from the lists that have followed.”

Courtesy of Lowery.

ICYMI: 7 quick tips for conducting tough interviews

Rukmini Callimachi is a correspondent for The New York Times covering ISIS, and an NBC contributor.

“I was a hungry freelancer in 2001 and had spent a less-than-fruitful year in India trying to make it as a foreign correspondent, when I contacted an editor at The Boston Globe. He was an alumni of my alma mater and he agreed to speak to me as part of an outreach program organized by my college’s career services office. I called him to ask his advice on how to make it as a foreign correspondent. I expected him to give me the names of whom to contact on the Globe’s foreign staff or, better yet, the contacts of assigning editors at the Times or The Washington Post.

He surprised, and frustrated, me by telling me that I needed to scale back my expectations and get a job at a small newspaper, doing a simple (read: boring) beat. ‘You’re going to make a lot of mistakes, and it’s best you make them at a small paper.’

I tried—and failed—to get so much as a call back from the top newspapers and finally landed a three-month internship at the Daily Herald of Arlington Heights, Illinois. My first beat was covering the city of Streamwood, Illinois, population circa 30,000. My internship led to a full-time job, earning $22,000 a year.

I was there for two years and it was two of the toughest years—but also two of the most foundational—of my career. I made numerous mistakes, ones which may have caused me lasting damage had I made them at a large-circulation daily. I wrote for an avid readership who cared about local news, which meant that when I screwed up, readers would call and leave me profanity-laced voicemail messages on my office landline.”

Julia Ioffe is a staff writer at The Atlantic who covers policy and world affairs.

“George Packer once told me before my first reporting trip to Russia: ‘Write about what’s interesting to you. The rest will follow.’ I’ve been following that advice ever since.”

Jaweed Kaleem is the national race and justice reporter at The Los Angeles Times.

“Write every story as if it is for page one.”

He says that advice was given by Reginald A. Stuart, a journalism recruiter, mentor, and diversity advocate who has worked for McClatchy and Knight Ridder, and was formerly a reporter for The New York Times.

ICYMI: While on air, authorities grab journalist and violently drag her

David Fahrenthold is a Pulitzer-winning Washington Post reporter.

“The advice I remember most is from Deborah Nelson, who’s now a professor at the University of Maryland. When I was an intern at the Seattle Times in 1998, she was an investigative reporter at the paper, and she did a little seminar on investigative reporting for us neophytes. I remember her advice about a big story: Imagine your story as a set of concentric circles, with the subject at the center. Start at the outer ring—with sources only distantly connected to the subject, and with documents—and work toward the center.”

Nick Corasaniti is a digital correspondent at The New York Times.

“I was a sophomore in college at Ithaca College in New York, in the school of communications, and they were making us do video editing—analog. I was all angry because I went there to become a newspaper reporter, a writer, and I felt like this was like a waste of my time and my very expensive tuition, so I went to the head of the journalism department [Mead Loop] and was like, ‘This is ridiculous; why am I doing this?’ And he said, ‘The journalism industry is changing; you need to be able to tell stories in every way possible. I don’t know how it’s going to change, but one of my former students just called me saying he got a job at The New York Times.’ And then he paused, and then he said, ‘for video. So if that’s his way into the Times and that’s where you want to go, you need to know how to tell a story in every different format.’

I kind of took that and ran with it at Ithaca; I learned how to video edit, I learned how to code, do digital journalism, and all those skills have helped me now. I never lost sight of approaching a story and thinking about what is the best way to tell this, not just in terms of my lede and my nutgraf, but in terms of platform. Should it be a video, should it be a graphic, or a social story? You have to be able to do it all in the current journalism environment.”

ICYMI: “I don’t tweet. I don’t care.”

Margaret Sullivan is The Washington Post‘s media columnist. Previously, she was The New York Times public editor.

“I’m really not sure where this came from because it’s essentially a Reporting 101 truism but still really helpful: Report against your own biases. That is, include the reporting that has a chance of proving you wrong, not just confirming what you already think or think that you know. At the very least, this will allow you to know in advance what the objections to a story might be. It tends to make reporting more fair—and more bulletproof.”

Robert Herguth is an investigative reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times.

Herguth shared some advice from his dad, 91-year-old Robert J. Herguth, a retired newsman who worked at the Chicago Sun-Times and the now-defunct Chicago Daily News:

“He told me before I started my first legit journalism job in 1992, at the City News Bureau of Chicago, a legendary journalism training ground, two things: If the editors ask you something, and you don’t know, say, ‘I don’t know, but I’ll find out.’ If you screw something up, say, ‘I’m sorry, it won’t happen again, and then make sure it doesn’t happen again.’”

ICYMI: Eight simple rules for doing accurate journalism

Diana Moskovitz is the senior editor at Deadspin.

When Moskovitz was 24 and just starting out as a breaking news reporter for The Miami Herald, she says she was a solid writer but a so-so reporter who got called out frequently by some of her editors, including Patricia Andrews, whose criticism could be harsh but always hit the nail on the head.

Moskovitz says she was sitting in Andrews’s office one day “getting schooled” when she gave her two bits of advice.

“She said, when you start anything, cast your net wide. Because you don’t know what’s going to be that person, or that document, or that spokesman, or that file, or that anything that unlocks this story for you. Take five minutes to think about every person, place, and thing involved, call all of them…and see what comes back,” says Moskovitz, sharing the first bit of advice.

The second piece of advice from Andrews, Moskovitz says, has to do with interviewing.

“She called me out. She said, ‘You’re getting sidetracked in all your interviews, clearly people are taking you off track or you’re letting them off track, you’re not getting what you need, and you need to call them back but you can’t do that on deadline; this paper’s going to press with or without you,’” Moskovitz says. “And she told me, ‘before you call a person, list every question you have for them at the very top of a document, and as you’re talking to them keep referring back to that, because that’s going to keep you on track.’”

Laila Al-Arian is a senior producer and investigative journalist for Fault Lines, Al-Jazeera’s award-winning documentary show.

“The best advice I’ve gotten about reporting is, ‘Do the reporting, and the story will write itself.’ The source is Sandy Padwe, my reporting and writing professor at Columbia Journalism School. I took his advice to mean that if you thoroughly and deeply report a story, do all the research and interviews you need to do to make it good, writing it will be easy because your material will be so strong that the story will write itself. I think a lot of reporters can suffer from writer’s block, but he was advising his students that will be much less likely if your source material is strong. And you’re more likely to get strong material if you thoroughly report a story. Even though I’ve since mostly switched to broadcast journalism from print, I think about and apply his advice all the time. I know that during pre-production I need to focus on gathering strong material, from convincing potentially hostile sources to talk to us on camera for accountability interviews, to finding compelling personal stories. If that’s accomplished, I know that the post-production process will go relatively smooth.”

T. Christian Miller is a senior investigative reporter at ProPublica and a Pulitzer Prize winner.

Miller says he got crucial advice from Terry McGarry, a legendary journalist known for his coverage of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and who was his editor at The Los Angeles Times. Miller says he was in the newsroom on the day McGarry, who was retiring, stood up and left his colleagues with these wise words:

“This can be an honorable profession—if you’re an honorable person.”

Tom Cole is the arts desk editor at NPR.

Cole says he received advice from former NPR cultural desk editor Sharon Ball that was “a matter of due diligence.”

“It was very simple: ‘Make ’em tell you no,’” Cole says. “Maybe we’re doing a story on a museum that has a supposedly looted work of art, and the reporter will say, ‘Well, the museum is not going to comment,’ and I’ll say, ‘Make ’em tell you no. Go back to them and ask them.’ And I think that’s the best bit of advice I’ve ever been given.”

Corey Johnson is an investigative reporter at the Tampa Bay Times and a co-founder of the Ida B. Wells Society.

Johnson shared advice from Dwight Cunningham, his former journalism fellowship instructor at the Diversity Institute, in Nashville, Tennessee.

“Trust but verify, which keeps me out of a lot of jams,” Johnson says. “And that’s crucial when you’re a reporter and showing up to a story or situation blind and somebody is being charming or very helpful on the surface; you still gotta double-check that information and make sure it’s accurate, because if you don’t, that’s when you run into problems. That’s when you lose your career, because the marketplace is less tolerant of that kind of tomfoolery by journalists. Everybody and their mama is hollering fake news these days.”

Ben Smith is the editor in chief of BuzzFeed.

“In my first reporting job, as a summer intern for the Forward, I passed on gossip a source in local New York politics had told me off the record, to another source. The second source told me: “If you’re telling me his secrets, you’re probably telling him mine. Now I know never to trust you.” I’ve been hyper-aware ever since that part of being a reporter is being genuinely trustworthy, and that you need always to be intensely aware of the status of information and of the agreements you make around it. (I recently read a version of that same story in Jake Adelstein’s book Tokyo Vice, which is a great reporting manual; he learned the lesson from a crafty cop in the Tokyo suburbs.)”

Jennifer Sabella is a deputy editor and director of social media at DNAinfo Chicago

“The best advice I’ve ever received is from Shamus Toomey (DNAinfo Chicago’s managing editor), otherwise known as the best boss ever: ‘Don’t f*** with the news.’

And in the ‘fake news’ era, that has never been more important. Leave the satire to the Onion and report the story—don’t make assumptions, don’t cut corners, and if something stinks, tell your editor.

To give credit where it’s due, Shamus got that advice from former Sun-Times Editor in Chief Don Hayner.”

Tina Rosenberg is a co-founder of the Solutions Journalism Network, and a writer for The New York Times‘ Fixes blog.

“Best advice from Medill’s J-school: At the beginning of every interview, tell subjects: I’ll ask you at the end: ‘Is there anything I should ask you about that I haven’t?’ Then ask it at the end.”

Rosenberg added another piece of advice she says she got from her colleagues at the Solutions Journalism Network: “Ask sources when you interview them about a problem: ‘Who’s doing a better job with this?’ Plenty of story ideas come out of that.”

ICYMI: What does it mean for a journalist today to be a Serious Reader?

Geoff Brumfiel is the science editor at NPR.

Brumfiel was a student at Johns Hopkins University’s science writing master’s program when a professor shared some simple wisdom with him about journalism.

“I’ve gotten a lot of advice over the years, but the best piece of advice was the first piece of advice I got, which is actually from a colleague here named Nell Greenfieldboyce, who walked into my class as a teacher and told me to go get clips,” Brumfiel says. “Nell’s advice was very concrete and very important: The best way to be a journalist is to go out there and pitch and be rejected and pitch again and eventually get something published, and keep doing it. Nobody takes you seriously until you start getting clips.”

Fernando Diaz is the digital managing editor at the San Francisco Chronicle.

Diaz passed along advice that editor Renee Trappe gave him when he was a younger reporter at the Daily Herald in suburban Chicago.

“The advice was the classic City News Bureau advice, which is, ‘If your mother says she loves you, check it out,’” Diaz says. “The most fundamental aspect of journalism is getting it right. It’s like the pushups and the crunches athletes do; at some point you still have to respect the fundamentals, no matter what level you’re operating at.”

Steve Coll is a staff writer at The New Yorker, a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize, and dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University.

“When I was starting out at The Washington Post, I once asked Bob Woodward how to ask government officials to share confidential or possibly classified documents or written materials. I thought that he must have some carefully sequenced strategy, arriving at a subtle request. ‘Just ask them,’ he said. ‘Don’t hesitate.’ Oh. That turned out to be very helpful as the years went by.”

Gay Talese is, well, Gay Talese.

“Shortly after I became a reporter at The New York Times, at 24, in the autumn of 1956, a venerated old-timer on the staff named Peter Kihss told me one day: ‘Young man, stay off the telephone. Show up in person. No matter how inconvenient it may be, always meet face-to-face with the person or people you’re interviewing. Stay off the phone. Show up. Look people in the eye. Observe everything first-hand. Be there!’ That advice was received more than 60 years ago, and I’ve followed it ever since.

I’m now 85. I am still a working reporter; and although most of my reportorial work these days appears in the form of books or magazine articles, it is always observed first-hand and is storytelling in form, with lots of descriptive scenes and dialogue whenever possible. I sometimes refer to my method as the ‘Art of Hanging Out.’ Once, in order to write a profile about a Chinese female soccer player, I flew to Beijing and spent five weeks researching her story while traveling with her team. On another occasion, I followed a Russian opera singer on tour from Moscow to Buenos Aires to Barcelona and finally to her performance on stage at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. When I was a young reporter, the telephone was the ‘new technology.’ Now, as I watch the new generation of journalists focusing all day on their laptops, and on their smartphones, pursuing stories diligently with their eyes and heads bent downward, I’m tempted to recall the words of the late Peter Kihss. ‘Stay off the phone. Look up. Observe things first hand. Be there!’”

ICYMI: A reading list for future journalists

Adeshina Emmanuel and Justin Ray are the authors of this article. Emmanuel is a Chicago-based journalist focused on race, class, inequality, social problems, and solutions who has been published in The New York Times, Ebony, Chicago Magazine, and by ATTN.com. He's a former reporter at the Chicago Reporter, Chicago Sun-Times, and DNAinfo Chicago. Follow him on Twitter @Public_Ade. Ray is the digital media editor of Columbia Journalism Review. Follow him on Twitter @jray05.