Neel Bate stumbled across his first copy of Bachelor magazine at a Hollywood Boulevard drugstore. It was March 1937, and Bate—a Seattle transplant in his early twenties who worked as an erotic artist—had just come into his sexuality. But he never saw stories about people like him on major newsstands.

Decades later, Bate wrote about his chance encounter with the inaugural issue of the magazine. “I picked up a copy and thumbed my way into it, barely believing my eyes,” he wrote, in the magazine In Touch for Men. Bachelor featured celebrities like Marlene Dietrich and Paulette Goddard, beloved in the queer community, plus men who Bate said were his idols: Buster Crabbe, Cary Grant, and Tyrone Power. Bate was particularly taken by one swimming-pool photo of Errol Flynn, who flashed what Bate called an “outrageously teasing smile” at the camera. On that day, Bate later wrote, “there were five or six of ‘us’ all looking at Bachelor.” One gay man sat next to Bate and said, knowingly, “This Bachelor is nifty, huh?” “Here at last,” Bate concluded, “was what looked to be ‘our’ publication.”

Finding an outlet that spoke to any segment of what we would today call the queer community, Bate wrote, required a good deal of “detective work.” There was Esquire, which was by no means a gay publication, but whose frank discussions of men’s fashion gave it a certain queer appeal. And there were bodybuilding magazines like Physical Culture that many gay and bisexual men latched on to in order to explore their sexualities.

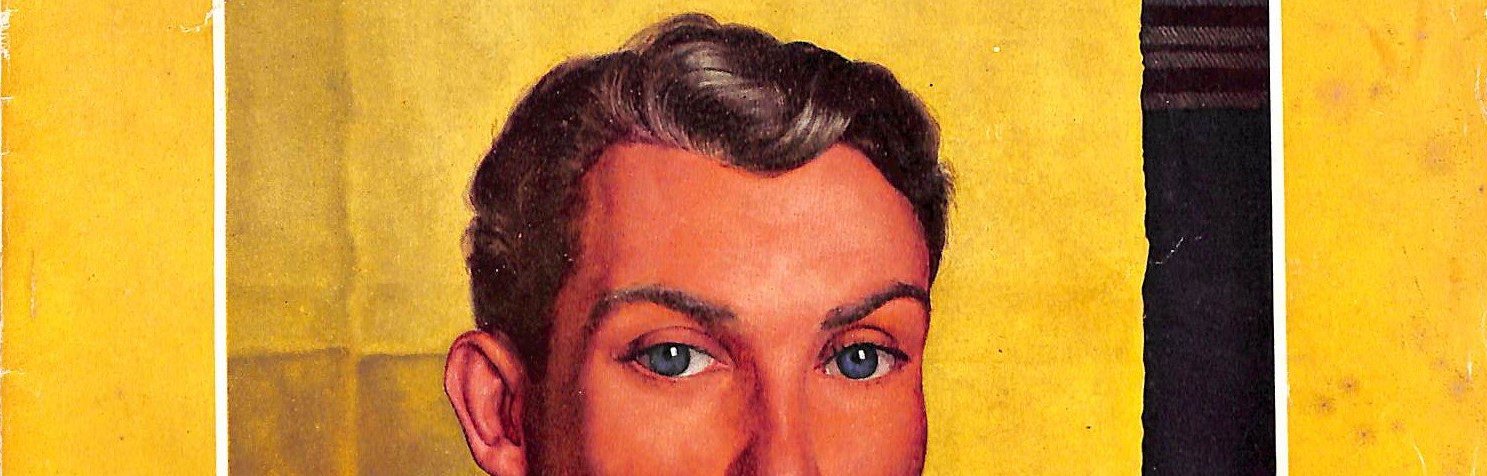

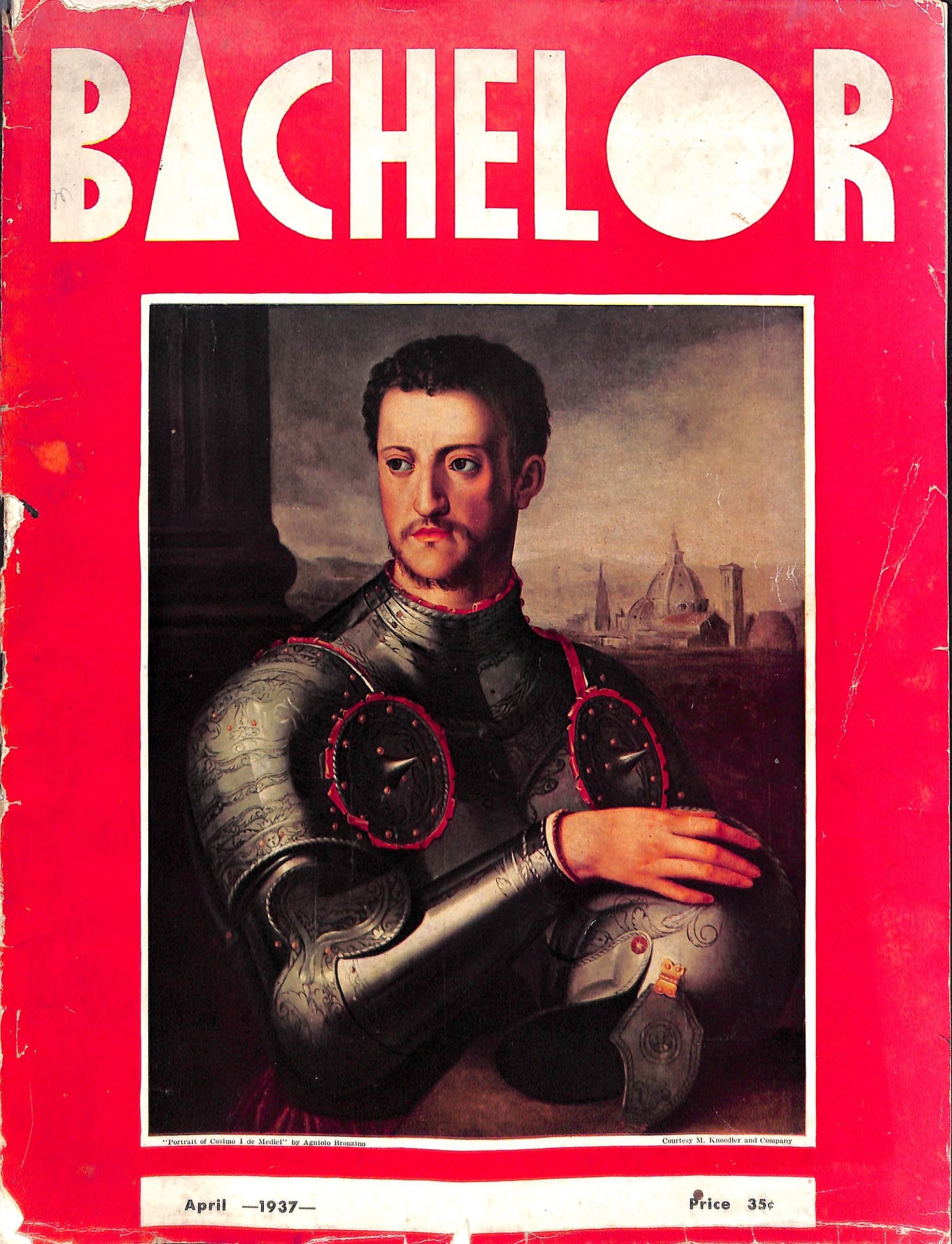

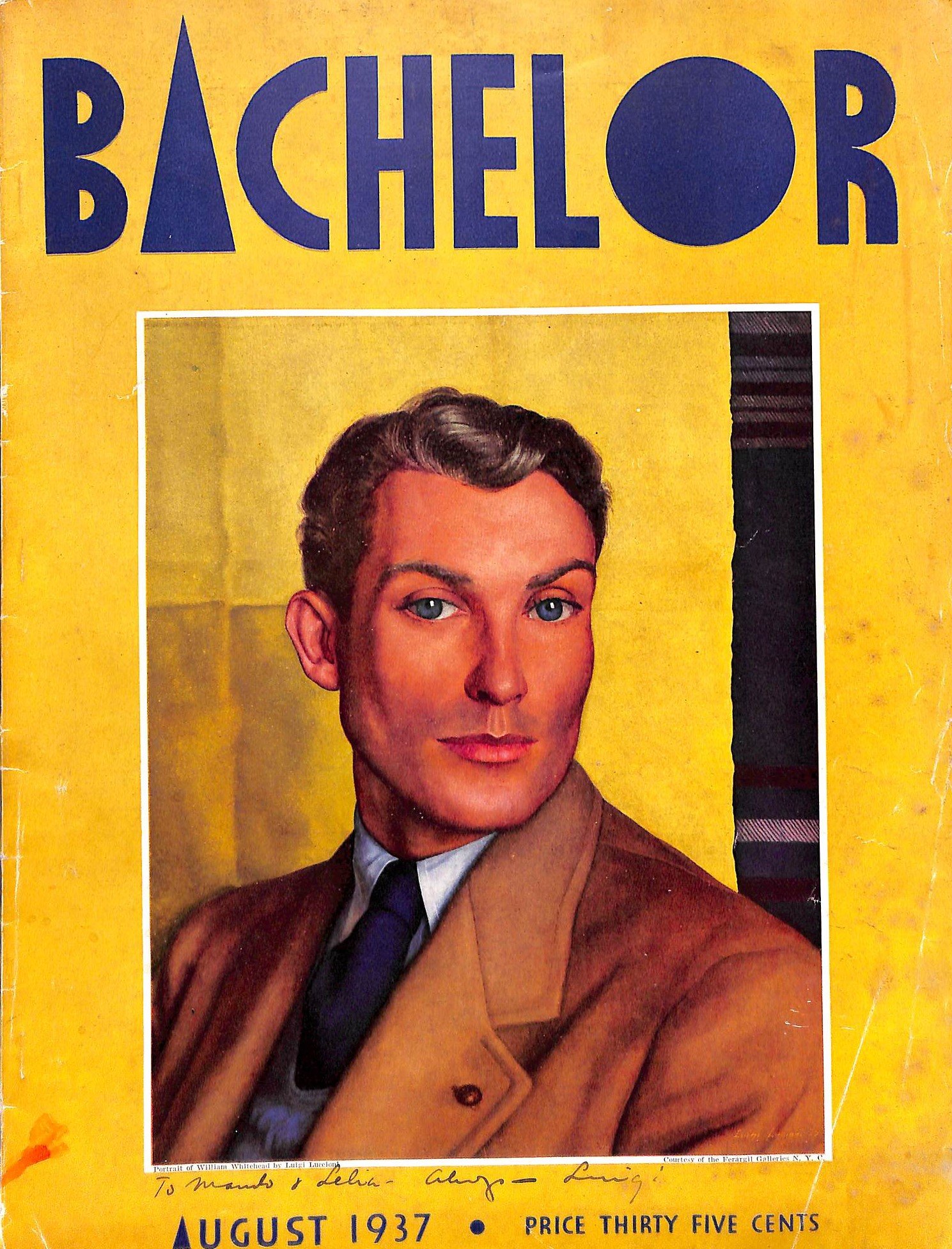

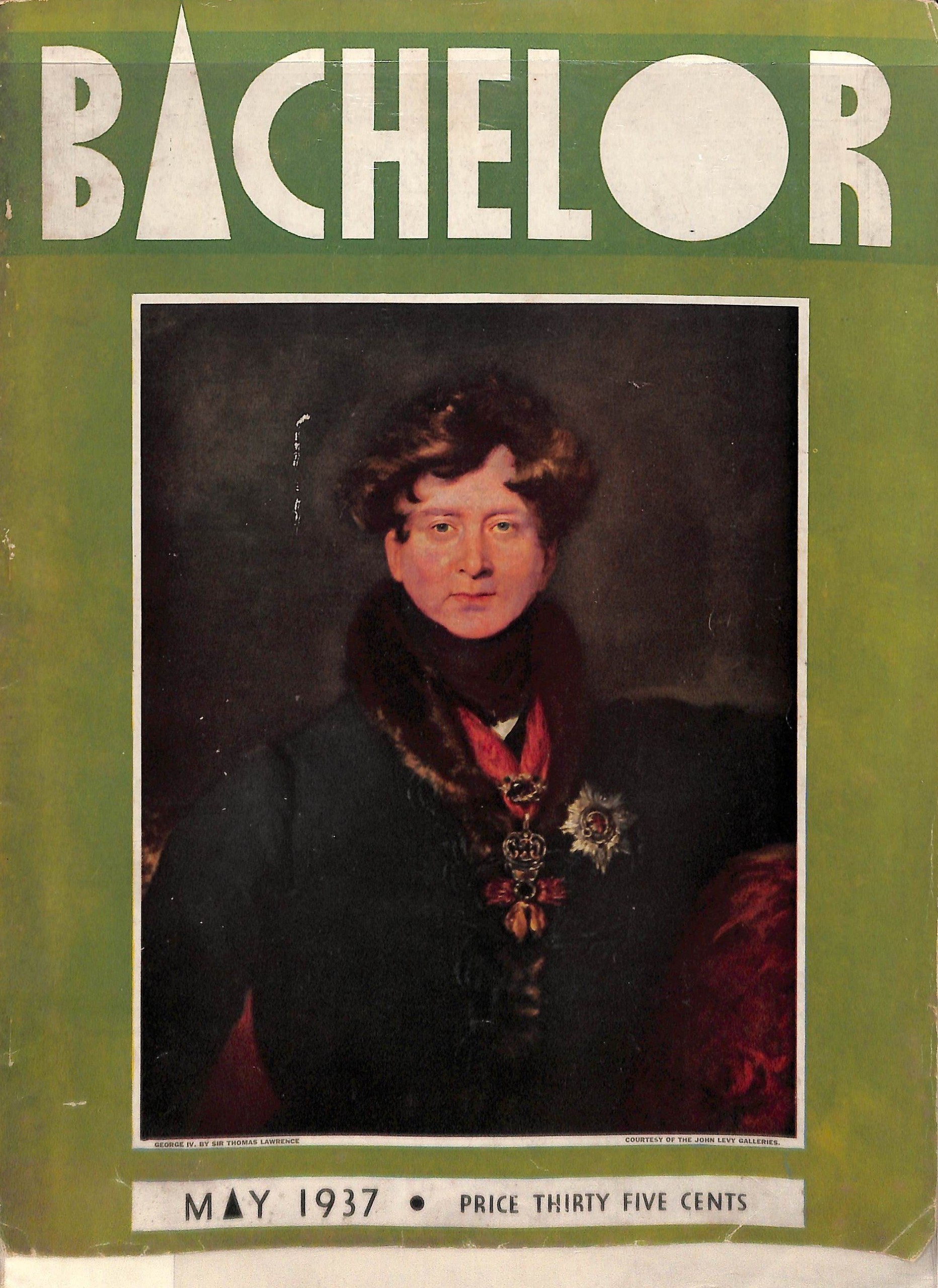

Then, suddenly, there was Bachelor. The magazine was hard to miss: it was glossy, as big as Vogue, and its covers featured close-ups of famous men against garish backdrops. Contemporary coverage said Bachelor was shipped to newsstands in every state and to Canada; Time described its target audience as “a social cut above Esquire’s.”

Courtesy of the Cary Collection

Bachelor announced that it was meant for the “discerning cosmopolite,” and specifically for single men. Many of its featured celebrities, as Bate described it, “seemed bent on avoiding marriage.” To a queer reader, that emphasis on bachelorhood brought to mind the phrase “confirmed bachelor”—a winking reference to a gay person. The magazine didn’t shy away from discussing the association between queerness and bachelorhood, often with a tellingly campy flourish. In that first issue, Bachelor lamented that “gossip about the whys and wherefores of bachelorhood usually tends to be vicious,” noting that men in club showers often made jokes about “some fellow’s lavender BVDs”—a type of underwear—“as though a taste for color necessarily implies a persistent thymus or a touch of Oscar Wilde.”

To most of the country, Bachelor was a flash in the pan. Despite recruiting big-name media talent like photographer Jerome Zerbe and earning a 50,000-copy print run, the magazine folded after a year, seemingly because readers found its “snob angle” off-putting, as syndicated columnist Walter Winchell put it. (A brief attempt to make it more folksy did not catch on.) But while Bachelor failed to make a ripple in larger US society, the queer people who saw themselves in it, like Bate, never forgot it.

Queer media in the first half of the twentieth century looked a lot like Bachelor: an assortment of queer-coded publications, many of which developed queer readerships seemingly without the knowledge of their publishers. Although very few publications explicitly said they were meant for the queer community, queer people made space for themselves anyway. They hijacked the personal-ads pages of fan magazines, sprinkled references to same-sex desire in general-interest publications, and kept up with homophobic press coverage in order to seek out cruising spots. This was an early iteration of queer media—a loose collection of pre-1950s publications that queer people coded as their own.

To understand what is so special about Bachelor, it’s important to note the context. In 1937, although queer nightlife thrived in major cities, there were no formal queer organizations. One of the first such groups, the Mattachine Society, did not arrive until 1950. The Daughters of Bilitis, a lesbian-specific group, appeared in 1955. ONE Magazine—often credited, dubiously, as the first gay magazine in the United States—didn’t start publishing until 1953. The main exception was a small Chicago group called the Society for Human Rights, which was raided by police in 1924. In a sign of the times, a Chicago Examiner headline dubbed the gay-rights group a “strange sex cult.” (The Society for Human Rights had a newsletter of its own, Friendship and Freedom—maybe the first explicitly queer publication in US history—but police confiscated it, and no copy survives.)

Meanwhile, publishing anything explicitly queer came with its own dangers. The Comstock Act classified any gay content as “obscene”; police would regularly shut down publications that spoke too frankly about homosexuality. The queer coding in magazines like Bachelor wasn’t just meant to wink at queer readers—it was also the only way a publication that wanted to discuss queerness could survive.

Bachelor entered newsstands amid that media abyss. And, as time wore on, it only seemed to get more queer. A typical article praised a watercolorist named James Reynolds for “conjur[ing] up so vividly…certain Greek gods and heroes.” One issue featured a sketch of two men holding hands; another featured an illustration of two naked women, who whispered to each other, “Don’t look now, but I think we’ve come up in the wrong magazine!” George Platt Lynes, a queer photographer, wrote for Bachelor about the “amorous regard” he developed for his subjects—for the sake of straight female viewers, of course. (In Work! A Queer History of Modeling, historian Elspeth H. Brown writes of Lynes’s piece, “The joke is on any chance heterosexual readership of Bachelor magazine, though not, of course, on the gay men who surely read it.”)

Courtesy of the Cary Collection

Yet Bachelor—like many of the early publications that referenced the queer community—did not entirely come from queer people. A woman named Elizabeth Criswell, who was born Bess Willis and also went by the name Betty, dreamed up the magazine by herself. Criswell, formerly an editor at the Van Wert Times, an Ohio newspaper, ran Bachelor from her home of Circleville, Ohio, under the pseudonym Fanchon Devoe. The rest of the staff was based in New York City, where Criswell regularly made trips. Her husband, Robert, was an attorney, and seemed to provide the funding for the publication. The couple also seemed well-connected to the highest social stratum: visitors to their Ohio home included the Russian prince Alexis A. Droutzkoy and Cornelius Vanderbilt IV.

Whether Criswell really wanted Bachelor to appeal to queer people is unknowable, though probably unlikely. There’s no evidence of her having a special knowledge of or relationship to the queer community. Rather, Criswell intended Bachelor as a flipping-the-script of gender politics: whereas plenty of magazines of the era sexualized women, Criswell wanted hers to cast a romantic spotlight on men. “Half the business of history has been investing women with romance,” she told reporters in January 1937, just a month before the official launch of Bachelor. “It’s time somebody started lending glamor to men, especially unmarried ones.”

Regardless of her exact intention, Criswell hired enough queer staff—a photo editor, Zerbe, who was gay and a fixture of New York high society; Lucius Beebe, a gay writer who penned articles and provided editorial guidance—that the magazine took on a queer aesthetic. Criswell wanted to apply a heterosexual female gaze to men and men’s fashion; in doing so, she created an opening for queer men to express their desires through Bachelor, too.

While Bachelor’s circulation was unmatched, it was not the only queer-coded publication of the early twentieth century. There were a smattering of magazines linked to the queer community; they included the Little Review (1914–29), a literary magazine run by a lesbian couple, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, and Fire!!, a 1926 Harlem Renaissance magazine that included stories from several queer Black writers. The writer Richard Bruce Nugent’s “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade,” which ran in Fire!!, featured a relationship between a Black man and a white man.

Other publications showed only contempt for the queer community—but queer people read them anyway. That was particularly true of 1920s tabloid magazines, which obsessively reported on goings-on in the queer community in a bombastic and cartoonishly offensive way. In 1924, the vicious New York City tabloid Broadway Brevities ran a thirteen-part series called “Nights in Fairyland.” Stories included an attempted exposé of New York lesbians, whom Brevities called “followers of the divine Sappho.” (Unfortunately, the writer was “unable to meet Lesbians at close range.”) By the 1930s, Brevities was regularly printing stories with headlines such as “FAG BALLS EXPOSED” and “QUEERS SEEK SUCCOR!” (in reference to cruising spots).

William Straw, a historian who studied Brevities, says that queer people likely read the tabloid in order to figure out which parties were worth attending. “If you were queer looking for a place to go, you would read these exposés that were damning of these places because that was your only way of knowing where to go,” Straw says. “It’s a kind of counter-reading, where readers are supposed to be shocked but they use it to tell them where to go.” He adds, “You could take the episodes of ‘Nights in Fairyland’ and publish it as a guidebook for gay tourists in New York.” In Gay New York, George Chauncey, another historian, wrote of Brevities that “the paper’s articles were so well informed and accurate in their coverage of the gay scene that many of them were almost surely written by lesbians or gay men.”

Courtesy of the Cary Collection

That sort of hijacking of mainstream publications was essential to how queer people located one another in the early part of the twentieth century. Bachelor, Fire!!, and Brevities became staples of a queer media diet in the 1920s and 1930s. But during the 1940s, a seemingly mundane publication called The Hobby Directory took the crown.

A high school teacher named Francis W. Ewing started The Hobby Directory in 1946. On the surface, The Hobby Directory pitched itself to anyone with a zany personal collection—say, stamps or model trains. The magazine’s main section was crammed full of personal ads, where some lonely men sought out fellow hobbyist pen pals.

To those in the know, however, some of the magazine’s personal advertisements carried their own code. Subscribers professed their fascination with “physical culture, wrestling, outdoor life” or their desire to make “friends among cowboys, sheepherders, miners, lumberjacks, ranch hands, sailors,” and “guys who wear Levis, cords, leather jackets with pep in their step and a sparkle in their eyes.” Martin Meeker, a historian who analyzed The Hobby Directory in his book Contacts Desired, encountered several men who seemed to be advertising erotic content—for instance, a Los Angeles subscriber who, in the June 1950 issue, boasted that his collections included “photos of physical activities” and said that he wanted to meet “other such collectors, weight-lifters, and athletic models.” Meeker also found copies in the personal archive of Bois Burk, a gay man who openly used The Hobby Directory to cruise for other gay men. In one copy, Burk wrote in the margins, “A truly beautiful experience I think / When true friends are made by pen and ink.”

“It’s pretty amazing how many people came across it, discovered it,” Meeker says. “At the time, the distribution networks were so small and so tenuous.”

In my research, I encountered a February 1955 letter that a gay man named Frank wrote to the Mattachine Review. Frank, who said he was trying to “meet fellow sufferers,” asked for recommendations of gay publications to read. “I have heard of a Hobby Directory, in which they give names for pen pals, how do you get the listing, and get into this pen pal thing,” he wrote.

In another case, federal authorities charged a Texas man named James McCabe for sending an “obscene letter” through the mail—a letter, authorities noted in the arraignment, that McCabe wrote to a man he had met in the pages of The Hobby Directory.

As was the case with Bachelor, to what degree the magazine’s publisher knew about his queer readership is up for debate. On one hand, Ewing did publish an eyebrow-raising screed in 1951 against people who “do not give their correct ages” in the magazine. His fury, he said, came from readers’ wanting to connect with their own generation… in order, he wrote, to trade “photos of young men in service uniforms.” But if Ewing did intend his publication as a ruse to facilitate gay meetups, his passion for hobbies was genuine. Back in 1933, years before The Hobby Directory existed, Ewing formed a thirty-five-person student hobbyist club as a teacher at Hackensack, New Jersey’s high school.

The reality, though, is that Ewing’s intentions don’t fully matter. As with Bachelor, queer people weren’t waiting for editorial approval to make space for themselves. They figured out how to build community with so much subtlety that the average reader would never have been able to pick up on the code. Only those in the know would.

Few queer-coded publications received the same level of circulation as Bachelor or The Hobby Directory, but it’s likely that dozens more existed in the early years of the twentieth century—we just don’t know about them yet. “I think there are probably more things out there like The Hobby Directory that could have been produced by queer people but were sufficiently coded that they would not have been discovered by people outside the community,” Meeker says. They might have made for an entire underworld of queer media: magazines that seemed to be only about one thing, but that queer people repurposed. As long as sympathetic writing on homosexuality was classified as “obscene,” they didn’t have any other option.

Michael Waters is a journalist interested in the forgotten parts of history. He's also currently a staff writer at Digiday.