I don’t know about you but my Facebook feed has gotten creepy and cringeworthy these days, and it’s thanks to news organizations.

Here’s a list of stories that have popped in my news feed in the last few days with my friends’ names and pictures attached and a message telling me they have read it:

— Snooki Poses in a Bikini For New Book Cover

— Drunken Wedding Guest Arrested – Slow Dances With Groom, Brawls With Bride

— ‘Ridiculously Photogenic Guy’ image goes viral

— Kristin Cavallari Glows With Her Baby Bump at Delta’s Pre-Grammy Bash (PHOTO)

— 35 Brutally Honest Reasons Men Say No to Sex

— Transgender model Jenna allowed to run for Miss Universe

A married friend read this one:

— When It’s Just Another Fight, and When It’s Over: A new type of therapy helps struggling couples decide whether to divorce or remain married.

And this one’s my personal favorite:

— What Was the Liquid Dripping Down Christina Aguilera’s Leg at the Etta James Tribute?

I know for a fact (they told me) that at least some of these people have no idea that their Facebook accounts are telling everyone they know the embarrassing stuff they’re reading. I suspect that most people aren’t aware that this is happening.

That many people don’t know that their reading habits are being shared with friends and family raises fairly serious ethical questions for news organizations (and for Facebook, which we know doesn’t care about them as they relate to privacy, anyway). Your reading habits can expose intensely private things about you, and you should know when they’re being exposed.

One of the most popular social news apps is run by the Washington Post, which is very proud of its success. It has indeed gone viral—and not all in the good sense. What do you call something that you don’t know about or forgot about that sits on your computer and automatically sends out personal information to others—information you don’t necessarily want them to have?

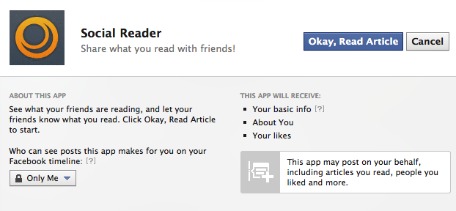

It’s true that to get installed on your Facebook account, these apps have to ask you to approve them. Here’s the Washington Post‘s screen, for instance:

The tagline up high is “share what you read with your friends!”, which sounds innocent and useful enough. I like to share links to stories I think other people should read. Up high it says, “Okay, Read Article,” and when you push that button, it installs the app. There’s nothing telling you directly that you’re installing an app. A box in the bottom corner says “This app may post on your behalf, including articles you read, people you liked and more,” but how many people actually read that? Your mom’s on Facebook now probably, as is mine—guaranteed she doesn’t understand what’s happening here.

Not only does this stuff show up in my news feed several times a day (Yahoo’s app is also a frequent offender), but you can also go in there and click on your friends who have the app to see what they’ve read. The history goes back months. Jeff Bercovici reported back in the fall that even if you set the Post‘s Social Reader to not let anyone see what you’ve read, friends can still go in and see what you’ve read. That’s egregious.

Again, this is all fine if people really know about all of this. But many of them don’t, especially with a feature like that.

I wrote this on Twitter this morning:

For God’s sake, people of Facebook–turn off your news apps. Your reading habits are embarrassing.

And Henry Blodget, shameless purveyor of the kind of clickbait that you’d be embarrassed to have others find out you read, pipes up to respond, “Nope. Just the truth.”

The truth, of course, is very often embarrassing, as Blodget, of all people, knows full well.

But the truth of what people actually read is irrelevant here. The point is that many, many people aren’t choosing to share their tabloid reading habits. They’re being forced to by major media organizations who profit by having them, often unknowingly, spam their friends with their content.

And that’s not right.

So if you’re on Facebook, go to your privacy settings, edit your “Apps and websites” settings, and delete these apps—or at least make sure they’re not sharing information you don’t want shared.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.