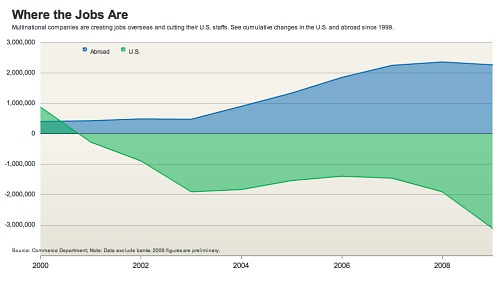

The Wall Street Journal has your chart of the day.

It shows that U.S.-based multinational corporations added 2.4 million workers overseas from 2000 to 2009, while cutting their U.S. workforce by 2.9 million.

These come from a The Wall Street Journal story by the paper’s economics editor David Wessel, who got these numbers from Commerce Department stats.

To put it another way, that’s a net loss of 5.3 million jobs (though, of course, not all of those overseas jobs could have been created here. Think a Walmart stocker in Mexico). These numbers go a long way toward showing why the American economy actually lost jobs in the last decade.

While multinationals account for just under a quarter of private-sector GDP, they were more a hindrance than a help for U.S. workers in the last ten years. The impact of the lost jobs and the jobs that could have been created here but went overseas thanks to our globalization policies is even higher than the actual figure. The wages and salaries not paid out here would have filtered through the economy creating a multiplier effect.

Alas, the Journal falls into a bit of he said-she said here:

Some on the left view the job trend as reason for the U.S. government to keep companies from easily exporting work overseas and importing products back to the U.S. or to more aggressively match job-creating policies used in some foreign markets. More business-friendly analysts view the same data as the sign that the U.S. may be losing its appeal as a place for big companies to invest and hire.

I’m not a fan, needless to say, of the language here comparing the arguments of “some on the left” to those of “more business-friendly analysts,” who are not only friendly, but analytical, too, apparently. How would it work if we flipped it: “More jobs-friendly analysts” versus “some on the right”?

Of course, it’s possible that both sides are correct. Here’s the “more business-friendly analyst” the Journal quotes immediately after that paragraph:

“It’s definitely something to worry about,” says economist Matthew Slaughter, who served as an adviser to former president George W. Bush. Mr. Slaughter, now at Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business, is among those who think the U.S. has lost some allure.

Presumably, Slaughter isn’t blaming his former boss, who was president for almost the entire decade, for the loss of American allure. But it’s certainly true that the U.S. is “losing its appeal as a place for big companies to invest and hire.” That’s just a fact borne out by that 5.3 million jobs gap. The question is why it’s losing its appeal.

One big reason is that big companies’ sales are increasingly coming from overseas.

The WSJ reports that General Electric, for instance, foreign sales now account for 60 percent of its overall revenue—double the number of a decade ago. But the paper misses by not telling us how much more business multinationals overall are doing overseas.

According to Standard & Poor’s, foreign revenues were 47 percent in 2009 for companies in the S&P 500, anyway, up from 32 percent in 2000.

But another big reason the U.S. has lost appeal as a place to create jobs is that companies have found that they can hire workers for cheap overseas and still sell goods here. That increases the profits available to pad out CEOs paychecks, which according to the AFL-CIO averaged $11.4 million for 299 of the biggest American companies.

What people like Slaughter are talking about when they talk about the U.S. losing its appeal for business is the fact that we have regulations that protect workers and the environment, taxes that pay for the empire and safety net we’ve installed, and wages that are more than, say, one-tenth of what Triangle Shirtwaist workers made a century ago—and other places don’t. The logic of free trade fundamentalism is that we have to lower our standards to those of the third world or our companies will just ship their jobs there, unless and until the third world raises their standards to ours. Either way, it won’t stop draining jobs here until there’s an equilibrium.

Which brings up a hole in this story: It doesn’t tell us anything about outsourcing overseas. I’m guessing that the 2.9 million number the Journal uses is for actual corporate employees and that it doesn’t include suicidal Foxconn workers snapping iPhones together in China for Apple Incorporated. But the paper doesn’t say. If I’m right, the numbers are even worse, though it’s possible that would make that U.S. job cuts numbers look better by counting work outsourced here.

But there’s lots of stuff to chew on here. Including this about Oracle:

Oracle, which makes business hardware and software, added twice as many workers overseas over the past five years as in the U.S. At the beginning of the 2000s, it had more workers at home than abroad; at the end of 2010, 63% of its employees were overseas. The company says it still does 80% of its R&D in the U.S.

Larry Ellison might as well be that prototypical CEO I talked about a few paragraphs up. His compensation from 2000 to 2009 while he was shifting jobs abroad? A cool $1.8 billion.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.