The Washington Post Company‘s dismal quarterly earnings release last week was received with something of a shrug—more of the same. But the report is worse than the reaction suggests and raises fundamental questions about the Post’s strategy, not just for the newspaper, but for the whole company.

If you hadn’t heard, the Washington Post Company is basically a for-profit college/SAT-prep firm that sidelines as a cable-TV provider and newspaper publisher. The august Washington Post (I’ll italicize Post here when referring to the newspaper and won’t when referring to its parent) contributed just 15 percent to its namesake company’s revenue in the first quarter but was a $23 million drag on the bottom line.

Kaplan, the Post’s education division, is the company’s cash cow, and a few years ago looked like the newspaper’s savior. But its revenue has fallen sharply over the last year and a half since for-profit schools, very much including Kaplan’s, came under pressure for predatory practices. Its sales tumbled 14 percent from 2010 to 2011 and dropped another 11 percent in the first quarter.

Its deteriorating prospects spells more trouble for the Post’s newspaper division, whose very bad first quarter included not only that $23 million loss but also a 7 percent decline in revenue. Crucially, its digital ad revenue—the paper’s main hope for the future—went into reverse and hit negative 8 percent. It’s just the latest in a long line of bad results.

The Post’s newspaper division (which includes Slate) has posted losses in thirteen of the last fifteen quarters, a trail of red ink that has led to cumulative losses of $412 million over the period. Its revenue has declined in twenty of the last twenty-two quarters and last year it brought in fully one-third less—$314 million—than it did at its peak in 2006. Layoffs have reduced the Post‘s newsroom to a little more than half its peak size.

Despite this, the company continues to fork over hundreds of millions of dollars to shareholders in the form of dividends and share repurchases. The Post is disgorging the cash, as JW Mason calls it, to investors and depriving its businesses of resources.

The company as a whole is still profitable and has earned a total of $546 million since the start of 2008, when the financial crisis began in earnest. But in that same time it has spent more than twice that—$1.1 billion—on buybacks and dividends that have helped put a floor under its share price (and its earnings per share).

Much of that money is being squandered to appease the short-term interests and cash needs of shareholders, who very much include the Graham family, which controls the voting shares of the Post.

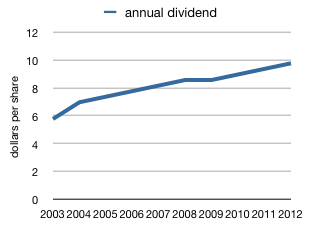

While the company has been bleeding revenue and income in the last year-plus, it has actually been increasing the amount of cash it pays out in dividends. Last year, it paid a $9.40 dividend for each share—a total cash payout of $75.5 million to shareholders. It has raised its dividend in nine of the last ten years for a total increase of 69 percent. The stock now yields a healthy 2.9 percent, a richer dividend payout than shareholders get from giant, cash-flush firms like Exxon Mobil, Apple, Microsoft, and Walmart.

This is like some kind of recurring nightmare for iconic American newspaper brands. It was only five years ago that Audit Chief Dean Starkman wrote this about Dow Jones, The Wall Street Journal’s publisher, which was bled dry by decades of dividend demands from the feckless Bancroft family.

A dividend is a cut of the profits earned by the business during the year. It is not guaranteed, and, in fact, must be set every quarter by a company’s board of directors. The idea is, you might need the money for something else at any time.

A dividend is capital that you are returning to shareholders because the business has no better use for it. No one believes DJ didn’t need to grow to remain independent. And does anyone believe the newspaper business isn’t in transition and that lots of capital might be needed to help with that shift?

Now of course, Dow Jones is stuffed and mounted in Rupert Murdoch’s man cave. Perhaps he can pick up the Post at some point.

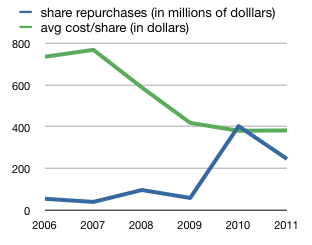

Even worse than raising dividends in a time of distress and disinvestment, the Post has binged on buying its own shares back from investors, spending $912 million since the program began six years ago and paying an average price of $424 a share. Those shares are worth $337 as I type, which means the Post has taken a $187 million bath on them—a 21 percent loss.

Particularly cringeworthy is the $198 million it spent buying its own shares from 2006 to 2008 at an average price of $661 each, or roughly double what they’re worth today.

As its share price has continued to fall, the Post has doubled down on its buybacks. In the last two years alone, the company has spent $653 million on share repurchases, buying in at an average $383 a share, 12 percent above their current price (a $79 million loss as of today).

This is financialization at work. Instead of investing in its business operations, the Post is investing in its stock, which is a very different thing. The only way this bet pans out is if the Post’s shares rebound significantly in coming years. Would you put money on that? I sure wouldn’t (moreover, the company effectively levered up to buy them. The Post rolled over $395 million in debt in early 2009 to mature in 2019—at a 1.75 percent premium to its old bonds).

Where would the Post be if its parent company had invested even one-quarter of that nearly one billion dollars in its newspaper, or in some other profit-making, preferably non-predatory venture? That’s unknowable, of course, but it’s worth thinking about when you ponder why newspapers haven’t better adapted to the digital age.

While the company has been throwing cash at shareholders, it has been gutting the Post‘s legendary—and critically important—newsroom, which, after the current round of buyouts and/or layoffs, will be a bit more than half what it used to be. This latest round of buyouts could reduce the investigative staff from seven to four.

By handing all that cash back to shareholders while disinvesting in its newspaper, the company is effectively saying that spending money on the hallowed Post is like throwing it down the rathole—it sees no possibility of making a return on any net investment there. That may actually be true, but it’s bad for the country, and it’s not very Swashbuckling Capitalist of them. The Post won’t take risks betting its cash on its namesake news organization’s future. It will unload nearly a billion dollars into its own pitiful stock. The “disgorge the cash” philosophy, which masquerades as flinty shareholder capitalism, is actually insecurity and weakness—an inability or unwillingness to invest that buyback/dividend money to come up with new products or to shore up old ones.

The Post would like you to think that it’s doing more with less, but that’s hamsterized nonsense. Then-managing editor Raju Narisetti’s assertion last summer, under a grinning mugshot and speaker-circuitese that “news brands need to get creative and make their content easier, more engaging and useful,” that he had slashed the newsroom by 25 percent “without overtly impacting quality” was as bogus as it was offensive. Ask anybody who read the paper before and after.

Narisetti wrote that those cuts helped the paper save $9.1 million a year on payroll and $14 million a year overall. Fabulous! But in 2010 and 2011, the Post handed $405 million a year back to shareholders through share buybacks and dividends. The losses on its share buybacks in 2010 and 2011 could have funded the savings from newsroom cuts in those years—three times over.

It’s not Narisetti’s fault, of course, that the folks in the C-suite told him to slash newsroom costs while they spent squandered hundreds of millions elsewhere. But when senior editors argue that you can lose hundreds of journalists without impacting the quality of the product (“overtly,” anyway; whatever that means), they make those short-sighted moves much easier for bean counters to make—and they demoralize what remains of their staff.

Narisetti’s comments were made in a Forbes column arguing that the Post shouldn’t charge online. The Post has maintained its anti-paywall stance even as its circulation continues to collapse and the paper’s digital ad revenue, a relatively puny stream on which it has hung its future, goes backward. FONtastic.

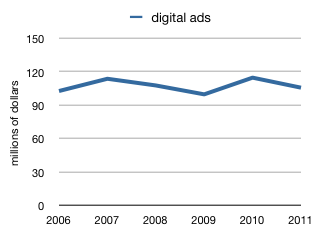

In the first quarter, the Post’s newspaper division (which includes Slate) brought in $24 million in digital ads, down $2 million from the year before, and less than what it made in the same period five years ago (the company doesn’t break out Slate’s numbers from the Post‘s, so we can’t tell from its filings whether one or the other was responsible for the decline, but I’d estimate very roughly based on Narisetti’s numbers that Slate accounts for about a quarter of the digital ads).

Last year, the Post brought in $106 million in online ads, less than the $114 million it collected in 2007. Here’s your “growth” story:

It’s even worse than that if you account for inflation. That $114 million in 2007 is $126 million in today’s money.

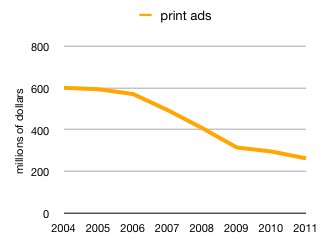

Print ads are, of course, in freefall at the Post like they are everywhere else. They totaled $265 million last year at the Post, 53 percent below the $573 million it had in 2006.

But the Post newspaper division’s total revenue has only declined 33 percent in that same time, while its one-time print gusher dries up much faster. What gives?

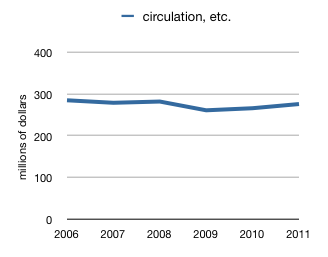

It’s almost certainly circulation. The Post for some reason doesn’t break out circulation revenue in its SEC filings, but we can back into those numbers by subtracting print and digital ad numbers from total revenue. This isn’t perfect—there are presumably some relatively minor “other” income streams caught in here, but it’s the best we’ve got (this is where I write that the Post declined to comment on its buybacks and dividends strategies and also declined to comment on my numbers).

Here’s a chart:

Circulation—people paying for newspapers—has been the ballast for the anti-paywall Post during the crisis.

How has the Post kept circulation revenue relatively flat while circulation numbers have collapsed? It has jacked up prices. From 2007 to 2012 the paper raised home delivery rates 76 percent.

The Post has diluted the quality of the newspaper, shrunk it, and asked readers to pay three-quarters more for it—all while leaving the barn door wide open online. And so, its daily circulation continues to plunge, falling 10 percent in the first quarter (29 percent from 2006), while Sunday circ—where the money is made—dropped 5 percent (25 percent since 2006).

Jacking up print prices while giving the same stuff away for free online might make a bit of sense if the paper’s digital ads were growing 20 percent a year. At minus 8 percent, as in the first quarter, it’s a death wish.

It’s particularly frustrating since The New York Times has done most of the hard work in showing how to have a successful paywall that brings in tens of millions of dollars, helps shore up print circulation, and doesn’t hurt online ads.

At Times Media Group (which is roughly two-thirds to three-quarters NYT), digital ad revenues increased 10 percent last year despite having the paywall in place for nine months. The Post‘s digital ads declined 8 percent without one. Overall revenue at the NYT, primarily as a result of the paywall, stayed flat last year, despite tumbling print ads. The Post‘s were down 5 percent.

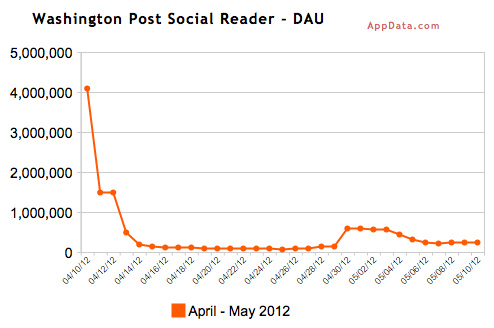

This despite the much (self) touted success of its annoying and ethically dicey Social Reader app on Facebook, which has been installed some 21 million times, according to CEO Donald Graham. That’s great and all, and it helps Graham pal Mark Zuckerberg’s company get more free content to make billions off of. But it’s apparently not doing much for the Post‘s digital revenue.

Last month traffic on social-news apps like the Post‘s collapsed after Facebook decided to tweak some settings, showing vividly the perils of relying on somebody else’s platform for your future prospects:

Now AdWeek reports that the Post’s president says the paper needs to think less about journalism awards and more about slideshows.

As we’ve seen just yesterday, the Post still puts out a good deal of top-level journalism in its weakened state. But that’s under continual threat, and the business side needs a serious change in philosophy to keep the Post from withering away.

UPDATE: Clay Shirky responds here and I reply here.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.