Programming Note: In place of our regular Media Today newsletter, CJR is pleased to share the Journalism Crisis Project—Lauren Harris’s weekly newsletter about the challenges facing the local journalism industry and how they might be overcome. The Media Today will return tomorrow.

Over the past year and a half, congressional officials have drafted a series of bills to address the beleaguered state of local media across the US. Thus far, only one piece of proposed legislation, the Local Journalism Sustainability Act, has made any significant progress. This summer, when bipartisan support for the act began to coalesce, Washington Post media columnist Margaret Sullivan wrote that congressional support “can’t happen soon enough.” Members of West Virginia University’s NewStart program—including Jim Iovino, the program’s director, and Crystal Good, founder and publisher of Black by God, both of whom have spoken to CJR about the importance of small-market journalism—wrote a letter calling the act “a game-changer for small-town USA.”

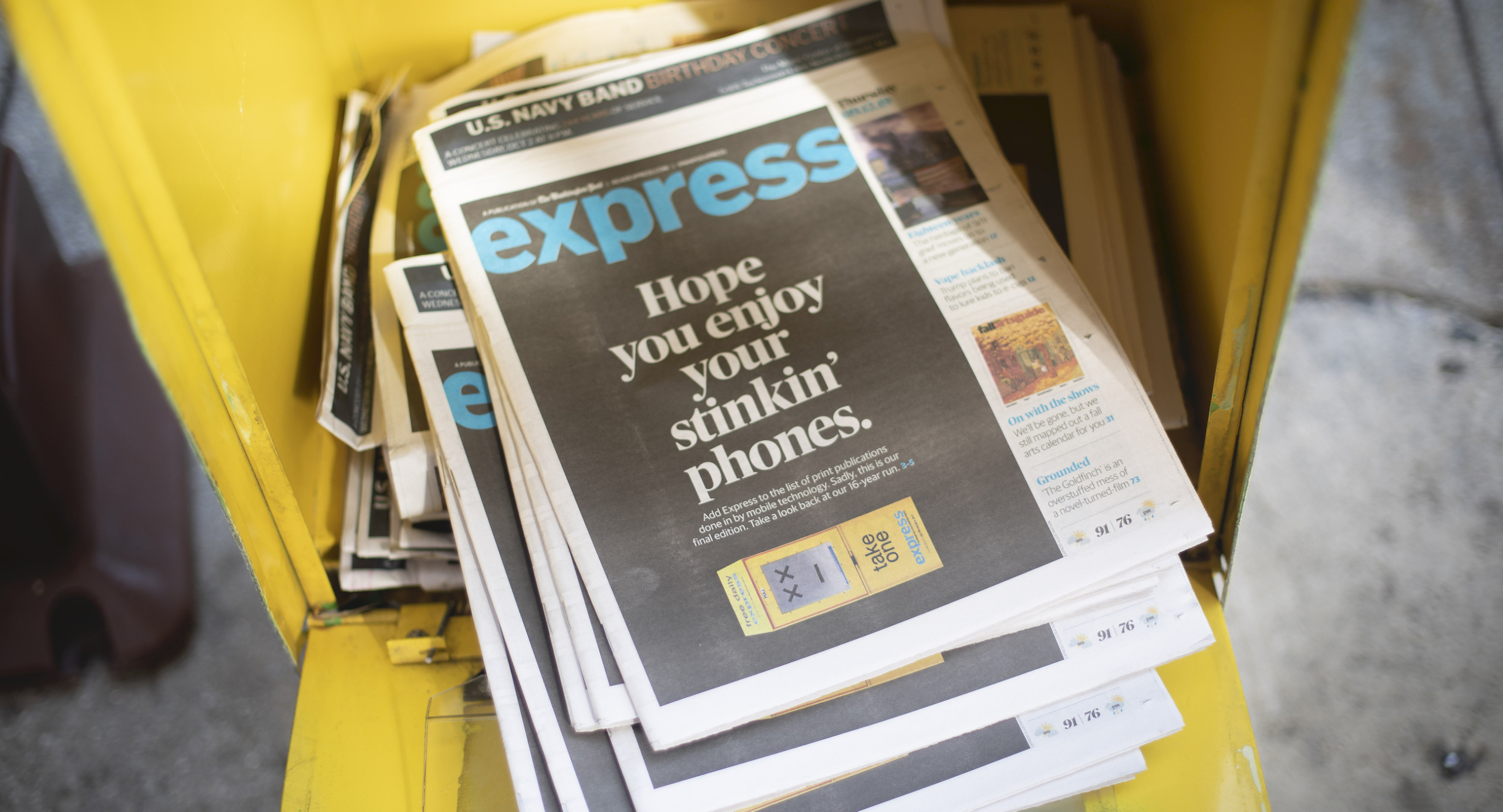

Recently, one provision from this act—a tax credit to pay a portion of local reporters’ salaries—has been included as part of the Build Back Better Bill, which Democrats hope to pass by the end of the year. Local news organizations that would benefit are urging their readers and elected officials to support the measure, as are many industry leaders. Early this month, the tax-credit provision was removed from the bill; in response, some local outlets ran false front pages or altered layouts in protest. The measure was then reinstated. Yesterday, the Long Beach Business Journal, in California, ran a blank print edition and homepage to represent “a future we never want to see happen,” publisher David Sommers wrote on Twitter. “A bipartisan-supported local news tax credit in the Build Back Better legislation would help newsrooms nationwide.”

The possibility of tax credits for local reporters’ salaries is something to celebrate, given the financial challenges facing most traditional local, for-profit newsrooms. Still, the Build Back Better bill includes only one provision from the Local Journalism Sustainability Act, excluding the original’s tax credits for advertisers and for local news subscribers. And given the act’s narrow focus on certain kinds of newsrooms, it’s only the very tip of the local-news iceberg.

It’s easy to criticize the legislation for not going far enough—it rarely does, in a system built on haggling at best and partisan obstruction at worst. But the passage of a tax credit to support local reporters’ salaries is a significant but preliminary step forward on the long road to healthy local information systems in the US. In September, I talked to people working in community news organizations, most of them non-profit, about the limitations of the Local Journalism Sustainability Act, which is, at its core, designed to prop up the traditional profit-based local news system. Such an intervention, they said, can only go so far. The salary tax credit is more applicable to nonprofit newsrooms than the act’s other provisions, but it still fails to more fully recognize the complex ways in which local information networks function in the 21st century.

Congress’s imagination is limited when it comes to information systems—as its clumsy hearings with social-media platform executives have demonstrated; such systems change quickly, and they’re complicated. When it comes to the topic of information access in local communities, the same may be said for media watchers and critics from time to time. (I’ve been immersed in reporting on local news for more than a year, and I’m frequently checking myself in terms of the way I think about “information deserts.”) It’s difficult to measure something as complicated as a community’s access to information, not least because every community is made up of communities, plural, and those are made up of individuals who approach information in a host of different ways. Access is complicated too. Not all barriers to information access are economic or even physical; sometimes, those barriers are cultural or psychological or even self-imposed. People have a diverse array of information needs—from investigations that hold local officials to account to civic knowledge that helps us navigate our daily lives, from beautiful stories that connect us to one another to practical information that tells us when to put out our trash or how to register for a COVID shot.

A “news desert” map is an illustration that helps us understand the crisis, but it can limit the ways we think about how communities exist and communicate. “In the absence of professional journalism—in so-called news deserts across the country—critical information systems are left to the algorithmic biases of a few social media giants,” wrote Darryl Holliday, co-founder of City Bureau, in an essay for CJR. “Dig further, though, and you’ll find block club newsletters, school newspapers, library workshops, public access broadcasts, grassroots community teach-ins, and barbershop conversations that are for and of communities.” Part of the solution lies in thinking more fully about the nature of local information and who is a partner in producing it. It’s inaccurate to think of traditional journalism as the only source of critical local knowledge. In all communities, many forms of information work in concert. Information networks require knowledge gathering and production, but they also require connection, communication, and collaboration.

A few weeks ago, I talked with Holliday about the journalism industry’s reluctance to see news consumers as information producers, too. To Holliday’s mind, at the hyper-local level, healthy information systems not only exist—they’re available as partners in the work of rebuilding larger local information systems, including local journalism. Such partnerships require thinking expansively about all the ways information works on the local level. “How do we reinforce the pipelines, the networks between these communities so that they are better able to do what they’re already doing?” he asked.

Our contemporary information infrastructure, and our select access to it, provides many of us with a tangled morass of content; it also erodes some of the better functions of the traditional press. Our local information systems—newspapers, sure, but also the myriad other ways news travels between people—hold potential solutions, and partners to help journalists secure them. Congress should be expansive in its approach to local journalism; the same goes for media watchers.

More on local journalism and community information:

- Sounding the alarm in Seattle: This week, the Seattle Times launched a new website dedicated to explaining the financial crisis facing local for-profit journalism. The site includes invitations to subscribe to the Times, a newsletter, and a link to donate to the paper’s investigative journalism fund. “With a cornucopia of reports, news stories, commentary, and other information, the site will hopefully be a resource for educators and those looking to learn more about the importance of the local press, the challenges it faces and what’s being done to save it,” editor Brier Dudley wrote in an announcement.

- Big plans in Salt Lake City: The Salt Lake Tribune, which last year became the first US metro daily to transition to a nonprofit model, announced that they will add more reporting staff and one more day of print publication, bringing weekly print editions back up to two days a week. “We celebrate 150 years this year and we are healthy,” executive editor Lauren Gustus writes. “We are sustainable in 2021, and we have no plans to return to a previously precarious position.”

- Community engagement in Long Beach: In August, the Long Beach Post concluded its first year employing a community editorial board made up of residents from across the city—created after the paper heard concerns from readers that the newsroom did not reflect the diversity of its surrounding community. The group met virtually each week, discussing potential coverage areas in addition to writing a few editorials per month; participants made $100 per meeting. For The American Press Institute, the Post’s community engagement editor Stephanie Rivera considers where the effort succeeded and where it fell short.

Other related links:

- Yesterday, a Connecticut state court ruled that conspiracy theorist and far-right media publisher Alex Jones was liable by default in the defamation case brought against him by the families of eight victims killed in the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook elementary school, the New York Times reported. Because Jones refused to turn over documents required by the court, the court rendered a default judgment. For years, Jones used his InfoWars site to promote the conspiracy that the Sandy Hook tragedy was staged by government gun-control advocates in a plot to take away citizens’ firearms. After he alleged that the victims’ families were actors, many of them received threats and harassment. Though Jones lost the suit, he plans to appeal.

- Also yesterday, the United States and China announced an agreement to ease restrictions on foreign journalists, making it easier for them to obtain visas, the New York Times reported. The Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, and the Times will all be able to return to China after being expelled from the country in 2020. It’s unclear whether the specific journalists expelled last year, during Trump’s tenure as president, will return.

- In Nicaragua, the state’s public prosecutor’s office has filed unspecified criminal charges against a journalism student named Samantha Jiron Padilla, who has been in prison since November 9, Havana Times reported. Padilla has been involved in political activism, and she previously supported the presidential primary campaign of Felix Maradiaga, who ran against the Ortega administration and is now in prison along with several other presidential candidates. “This summer has seen the Ortega administration grow increasingly brazen in its attacks on journalism,” my colleague Savannah Jacobson wrote in September, noting that at least twenty-six journalists had gone into exile between June and August. For more on Nicaragua’s deteriorating press freedoms, see CJR’s June photo series by award-winning Nicaraguan photographer Oswaldo Rivas.

- For the New York Times, Columbia journalism professor (and CJR contributor) Bill Grueskin wrote about corporate media’s widespread acceptance of the Steele dossier when it was first reported in 2017. He attributes some of the industry’s credulousness to journalists’ assumptions about the likelihood of the dossier’s veracity, in addition to a hesitance to be skeptical about reporting that indicted then-president Trump. “Newsrooms that can muster an independent, thorough examination of how they handled the Steele dossier story will do their audience, and themselves, a big favor,” Grueskin writes. “They can also scrutinize whether, by focusing so heavily on the dossier, they helped distract public attention from Mr. Trump’s actual misconduct.”

- Ohio is suing Facebook’s parent company, Meta, on behalf of the Ohio Public Employees Retirement System, claiming that Facebook violated federal securities laws when it misled the public about what research had shown about its negative effects on children. The state is seeking more than $100 billion in damages, The Verge reported.

- Pressure from new autonomous publishing platforms like Substack has pushed many legacy news outlets to create offers that give writers better flexibility and pay, Axios wrote yesterday. A few examples: The Atlantic recently rolled out a newsletter project with nine contracted writers (some from Substack), offering them opportunities to freelance and giving them a cut of subscriber revenues. The New York Times has put some of their opinion columnist newsletters behind paywalls. Forbes launched a newsletter platform that splits revenues with writers. “Journalists that crave the infrastructure and editorial support offered by newsrooms are finding more happy mediums as the newsletter industry grows,” Sara Fischer writes.

- According to a new report from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, about a third of newsrooms surveyed have adopted a long-term remote or hybrid-working model, and many more are open to the idea. Fewer than one in ten reported plans to return to pre-pandemic work expectations.